Sinharaja Forest Reserve Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SACON News Vol 18 1

SACON News Vol. 18 (1) January – March 2021 Institutional Events Popular Articles New Director in charge, SACON 1 Studying a Wetland: Challenges 5 and Concerns Webinar on Wetlands 1 By Mythreyi Devarajan Webinar talk at Central 2 University of Kerala on the Beginnings to Big innings 9 occasion of National Science By Gourav Sonawane Day, 2021 Birds and invasives: An 11 Webinar talk at the 3 observation on Plum-headed International Symposium Parakeet Psittacula cyanocephala “Conservation of Life Below feeding on Parthenium Water” (COLIBA-2021) By Gayathri V, Thanikodi M organized by University of Kerala Talk at an online training 3 Researchers’ Corner— programme organized by Indian Art & Conservation Institute of Soil and water conservation Freezing a few moments with my 12 gregarious mates World Water Day 2021 4 By Priyanka Bansode Research Aptitude 4 An Illustration of Agamids and 13 Development Scheme (RADS) other lizards of Kerala digitally launched at Payyannur By Ashish A P college, Kerala Cover Page Photograph Credits Front: Indian Robin Feature Article Image ©Shantanu Nagpure ©Priyanka Bansode Back: Eurasian Collared Dove ©Deepak D. SACON News Vol 18(1), 2021 From the Director’s Desk It is my pleasure to invite the readers to this issue of SACON News. While we all hoped the New Year to have given us relief from Covid-19, unfortunately it has bounced back, perhaps with vengeance restricting our regular activities. Nevertheless, we got accustomed to an extent with many ‘new normals’, and continued with our tasks, nonetheless adhering to Covid-Appropriate norms. This issue of SACON News covers major activities of the institute and interesting articles from our research scholars. -

Zoology ABSTRACT

Research Paper Volume : 3 | Issue : 9 | September 2014 • ISSN No 2277 - 8179 New record of Roux’s Forest Lizard Calotes Zoology rouxii (Duméril & Bibron, 1837) (Reptilia: KEYWORDS : Calotes rouxii, range exten- Squamata: Agamidae) from Sandur and sion, distribution update, Karnataka Gulbarga, Karnataka, India with a note on its known distribution Biodiversity Research and Conservation Society, 303 Orchid, Sri Sai Nagar Colony, Aditya Srinivasulu Kanajiguda, Secunderabad, Telangana 500 015, India. Natural History Museum and Wildlife Biology and Taxonomy Lab, Department of Zoology, * C. Srinivasulu University College of Science, Osmania University, Hyderabad, Telangana 500 007, India. *Corresponding Author ABSTRACT Roux’s Forest Lizard Calotes rouxii (Duméril & Bibron, 1837) is chiefly a forest-dwelling draconine agamid that is widely distributed in the Western Ghats and occasionally reported from the Eastern Ghats and other localities in the central peninsular India. We report the presence of this species for the first time from Sandur forests in Bellary district, Karnataka based on a voucher specimen and from Gulbarga township based on sighting record. A detailed distribution map showing localities from where the species is known is also provided. The genus Calotes Daudin, 1802, belonging to the draconian fam- ized by the presence of a dewlap in males, two slender spines on ily Agamidae (Reptilia) is native to South Asia, South-East Asia either side of the head and a dark groove before the shoulder. and Southern China. It is represented -

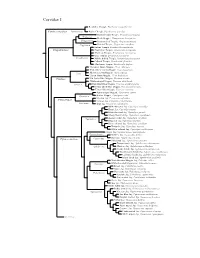

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

Contents/Lnhalt

Contents/lnhalt Introduction/Einfiihrung 6 How to use the book/Benutzerhinweise 9 References/Literaturhinweise 12 Acknowledgments/Danksagung 15 AGAMIDAE: Draconinae FITZINGER, 1826 Acanthosaiira GRAY, 1831 - Pricklenapes/Nackenstachler Acanthosaura armata (HARDWICKE & GRAY, 1827) - Armored Pricklenape/GroGer Nackenstachler 16 Acanthosaura capra GUNTHER, 1861 - Green Pricklenape/Griiner Nackenstachler 20 Acanthosaura coronata GUNTHER, 1861 - Striped Pricklenape/Streifen-Nackenstachler 21 Acanthosaura crucigera BOULENGER, 1885 - Masked Pricklenape/Masken-Nackelstachler 23 Acanthosaura lepidogaster (CUVIER, 1829) - Brown Pricklenape/Schwarzkopf-Nackenstachler 28 Acanthosaura nataliae ORLOV, NGUYEN & NGUYEN, 2006 - Natalia's Pricklenape/Natalias Nackenstachler 35 Aphaniotis PETERS, 1864 - Earless Agamas/Blaumaulagamen Aphaniotis acutirostris MODIGLIANI, 1889 - Indonesia Earless Agama/Spitzschnauzige Blaumaulagame 39 Aphaniotis fusca PETERS, 1864 - Dusky Earless Agama/Stumpfschnauzige Blaumaulagame 40 Aphaniotis ornata (LIDTH DE JEUDE, 1893) - Ornate Earless Agama/Horn-Blaumaulagame 42 Bronchocela KAUP, 1827 - Slender Agamas/Langschwanzagamen Bronchocela celebensis GRAY, 1845 - Sulawesi Slender Agama/Sulawesi-Langschwanzagame 44 Bronchocela cristatella (KUHL, 1820) - Green Crested Lizard/Borneo-Langschwanzagame 45 Bronchocela danieli (TIWARI & BISWAS, 1973) - Daniel's Forest Lizard/Daniels Langschwanzagame 48 Bronchocela hayeki (MULLER, 1928) - Hayek's Slender Agama/Hayeks Langschwanzagame 51 Bronchocela jubata DUMERIL & BIBRON, 1837 - Maned -

Sri Lanka 20Th to 30Th November 2013

Sri Lanka 20th to 30th November 2013 Sri Lanka Blue Magpie by Markus Lilje Trip Report compiled by Tour Leader Markus Lilje Tour Summary Sri Lanka is a very special birding island, where verdant tropical rainforest hosts a staggering bounty of endemic birds and you seem to get some of the major attractions of the Indian subcontinent without many of the problems that are associated with it. As soon as we touched down near Colombo and the group was complete, we wasted no time at all and began our travels into the heart of the country; our first destination being one of Sri Lanka’s most famous forest reserves, namely Kithulgala. Many rice paddies along the way provided the first bit of excitement with White-throated Kingfisher, Black-headed Ibis, Asian Openbill and a number of heron species all proving to be common. Layard’s Parakeet by Markus Lilje RBT Sri Lanka Trip Report November 2013 2 Our lodge here was positioned along the Kelani River, with excellent forest in close proximity while also allowing easy access to the primary forests on the opposite bank. These forests hold a number of excellent endemics and we were all eager to start our birding in this area. Success was almost immediate as we birded some rather open areas and gardens in the town itself, where we found our first endemics and other specials that included Layard’s Parakeet, the very tricky Green- billed Coucal, the beautifully patterned Spot-winged Thrush, Stork- billed Kingfisher, Sri Lanka Grey Hornbill, Orange Minivet, Chestnut-backed Owlet, Orange-billed Babbler, Golden-fronted Leafbird, Sri Lanka Hanging Parrot and Yellow-fronted Barbet. -

Worldwidewonders 57

WorldWideWonders 57 EXPLORING THE HORTON PLAINS SRI LANKAN HIGHLANDS Endless grasslands, gently rolling hills and mist-shrouded cloud forests at altitude showing a dazzling biodiversity and countless endangered endemisms 58 Tree Rhododendron Rhododendron arboreum along a slow-flowing, crystal-clear mountain brook in the Horton Plains National Park, Central Highlands of Sri Lanka. On the previous page, adult male Sri Lankan sambar deer Rusa unicolor sub. unicolor, in the typical gently rolling grassland landscape of the area. 59 TEXT BY ANDREA FERRARI PHOTOS BY ANDREA & ANTONELLA FERRARI orton Plains National Park is a spotted cat, Sri Lankan leopards, wild Hprotected area in the central highlands of boars, stripe-necked mongooses, Sri Sri Lanka, covered by montane grassland Lankan spotted chevrotains, Indian and cloud forest. This plateau at an altitude muntjacs, and grizzled giant squirrels, with of 2,100–2,300 metres (6,900–7,500 ft) the Horton Plains slender loris Loris is rich in biodiversity, and many species tardigradus nycticeboides, one of the found here are endemic to the region, world's most endangered primates, found designated a National Park in 1988. The only here. Together with the adjacent Peak Horton Plains are the headwaters of three Wilderness Sanctuary, Horton Plains major Sri Lankan rivers - the Mahaweli, contains 21 bird species which occur only Kelani, and Walawe. Mean annual rainfall on Sri Lanka. Four - Sri Lanka blue magpie, is greater than 2,000 millimetres (79 in), Dull-blue flycatcher, Sri Lanka white-eye, and frequent cloud cover limits the amount and Sri Lanka wood pigeon - occur only in of sunlight that is available to plants. -

New Records of Lizards in Tura Peak of West Garo Hills, Meghalaya, India

Journal on New Biological Reports 3(3): 175 – 181 (2014) ISSN 2319 – 1104 (Online) New records of lizards in Tura peak of West Garo Hills, Meghalaya, India Meena A Sangma and Prasanta Kumar Saikia* Animal Ecology & Wildlife Biology Lab, Department of Zoology, Gauhati University, Gauhati, Assam 781014, India (Received on: 04 August, 2014; accepted on: 13 September, 2014) ABSTRACT Intensive survey has been carried out from January 2012 to December 2013 and whatever we have uncovered from Tura peak was photographed and its measurement was taken. The data of Lizards were collected by Active Searching Methods (ASM). Most of the lizard survey was done during the day time as lizards and skinks are seen basking in the sun during the day hours. The identified species of Lizards, geckoes and skinks were photographed and released into their natural habitat. Altogether four species of lizards have been recorded newly in Tura peaks of West Garo Hills of Meghalaya States of North east India. The species were such as Calotes maria and Ptyctolaemus gularis from Agamidae Family and Hemidactylus flaviviridis and Hemidactylus garnooti from Geckonidae Family. All those four species have not been reported from Garo hill in past survey, whereas the species Hemidactylus flaviviridis not been reported from any area of Meghalaya state till date. Key words: New records, Lizards, Tura Peak, measurements, active searching. INTRODUCTION species are so far recorded in the North East India India is incredibly rich in both floral and faunal (Ahmed et al. 2009) and 26 species are represented species but, most of the studies of reptiles has been th in Meghalaya (ZSI,1995). -

Second Supplement to the Gibraltar Gazette

SECOND SUPPLEMENT TO THE GIBRALTAR GAZETTE No. 4818 GIBRALTAR Friday 5th February 2021 LEGAL NOTICE NO. 117 OF 2021. EUROPEAN UNION (WITHDRAWAL) ACT 2019 TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA (COUNCIL REGULATION)(EC) NO 338-97) (AMENDMENT) REGULATIONS 2021 In exercise of the powers conferred upon him by Article 19(5) of Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97 on the protection of species of wild fauna and flora by regulating trade herein, the Minister has made the following regulations- PART 1 Title. 1. These Regulations may be cited as the Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97)(Amendment) Regulations 2021. Commencement. 2. These Regulations come into operation on 14 February 2021. Amendments to the Annex to Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97. 3. The Annex to Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97 on the protection of species of wild fauna and flora by regulating trade therein is amended as follows. 4. In the section headed “Notes on interpretation of Annexes A, B, C and D”, in paragraph 12 after annotation #17 insert- “#18 Excluding parts and derivatives, other than eggs.” 5. The table which sets out Annexes A to C is amended in accordance with regulations 6 to 8. 6. In the rows relating to Eublepharidae, for the row relating to Goniurosaurus spp.(II) substitute- Gibraltar Gazette, No. 4818, Friday 5th February 2021 “Goniurosaurus Tiger geckos spp. (II) (except the species native to Japan and the species included in Annex C) Goniurosaurus Kuroiwa’s kuroiwae (III ground gecko Japan) #18 Goniurosaurus Japanese cave orientalis (III gecko Japan) #18 Goniurosaurus Sengoku’s gecko sengokui (III Japan) #18 Goniurosaurus Banded ground splendens (III gecko Japan) #18 Goniurosaurus Toyama’s ground toyamai (III gecko Japan) #18 Goniurosaurus Yamashina’s yamashinae (III ground gecko”. -

2018 Species Recorded SRI LANKA

SPECIES RECORDED SRI LANKA Jan 8-18, 2018 The 1st number represents the maximum number that species was seen in one day. The 2nd number represents the number of days that species was seen out of the 11 day trip. Itinerary - Negombo; Sinharaja & Kira Wewa Lake; ! - Horton Plains NP & Nuwara Eliya - Victoria Park, Hakgala Botanical Gardens, Surrey Sanctuary, Ravana Falls; ! - Yala NP; Tissa Wetlands; Nimalawa Lake; Bundala NP; !BIRDS Grouse, Pheasants & Partridges : Phasianidae Sri Lanka Spurfowl Galloperdix bicalcarata ! Endemic. A pair at the ‘spurfowl house’ in Sinharaja. Heard on other days there. 2/3 Sri Lanka Junglefowl Gallus lafayetii ! Endemic. A few seen each day in Sinharaja, Horton Plains and Yala. 4/9 Indian Peafowl Pavo cristatus ! Common in Yala and Bundala. 30/5 Ducks, Geese & Swans : Anatidae Lesser Whistling-duck Dendrocygna javanica ! Common in Yala and Bundala. 100/5 Cotton Pygmy-goose Nettapus coromandelianus ! A pair in Yala. 2/1 Garganey Anas querquedula ! A few in Yala and hundreds at Bundala. 300/2 Grebes : Podicipedidae Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis ! Individuals in Yala. 1/3 Storks : Ciconiidae Painted Stork Mycteria leucocephala ! Common in Yala and Bundala. 25/5 Asian Openbill Anastomus oscitans ! A few around Sinharaja and more seen in Yala. 10/7 Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus ! A pair on the way to Nuwara Eliya and a few in Yala. 4/3 Lesser Adjutant Leptoptilos javanicus ! 1 in Bundala. 1/1 Ibises & Spoonbills : Threskiornithidae Black-headed Ibis Threskiornis melanocephalus ! Common in Yala and Bundala. 30/6 Eurasian Spoonbill Platalea leucorodia ! A few seen in Yala and Bundala. 12/3 Herons & Egrets : Ardeidae Yellow Bittern Ixobrychus sinensis ! 2 seen in near Negombo airport and 1 at Yala. -

Sri Lanka – Blue Whales &

Sri Lanka – Blue Whales & Leopards with Sinharaja Extension Naturetrek Tour Report 3 - 15 February 2018 Blue Whale Risso’s Dolphin Leopard Sri Lanka Blue Magpie Report & images compiled by Mukesh Hirdaramani Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ England T: +44 (0)1962 733051 F: +44 (0)1962 736426 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Sri Lanka - Endemic Birds Tour Report Tour participants: Mukesh Hirdaramani, Saman Kumara & Dinal Samarasinghe (leaders) With 16 Naturetrek clients Highlights/Summary Blue Whales, Spinner Dolphins, Risso’s Dolphins and Bottlenose Dolphins were plentiful during our three day whale watching excursion, and calm weather created the ideal conditions for viewing. We had very good sightings of Blue Whales less than 20 metres away from our boat, and with every passing minute we were surrounded by many more. The visit to the Turtle Conservation Centre to see the Loggerhead, Green, Hawksbill and Olive Ridley Turtles was enjoyed by all, as was the visit to the Galle Dutch Fort with good views of the sunset over the ramparts. Lunugamwehera National Park yielded a superb sighting of Leopard as we entered, with two young Leopards sitting in the middle of the road. Birds including Sirkeer Malkoha, Barred Buttonquail, Velvet-fronted Nuthatch and Chestnut-headed Bee-eater were sighted during our safari here. Yala yielded more spectacular Leopard sightings, along with Asian Elephants and Samba and Spotted Deer. Overall we saw 27 species of mammal, 15 of reptiles and amphibians, and 194 bird species to conclude another successful tour. Day 1 Saturday 3rd February The tour started with an overnight flight from the UK to Sri Lanka. -

The Establishment of the Crested Tree Lizard, Calotes Versicolor (DAUDIN, 1802) (Squamata: Agamidae), in Seychelles

MATYOT, P. 2004. The establishment of the crested tree lizard, Calotes versicolor (DAUDIN, 1802), in Seychelles. Phelsuma 12: 35—47 The establishment of the crested tree lizard, Calotes versicolor (DAUDIN, 1802) (Squamata: Agamidae), in Seychelles PAT MATYOT C/o SBC, P.O. Box 321, SEYCHELLES [[email protected]] Abstract.— There is evidence that the Asian agamid Calotes versicolor (DAUDIN, 1802), the crested tree lizard, is now established on Ste Anne Island in Seychelles, and it is reported to be dispersing away from its original point of introduction. Data collected outside Seychelles on its habitats, reproductive biology and feeding habits show that this species is adaptable, prolific and omnivorous, and it is considered to be an invasive alien species that competes with or feeds on native biota in some parts of the world, such as Singapore and Mauritius. The Ste Anne population needs to be studied and, if possible, eradicated, to prevent this potential ecological threat from reaching other islands in Seychelles, especially those that harbour significant populations of native animals. Keywords.— Calotes versicolor, Seychelles, Ste Anne, invasive alien species. INTRODUCTION The crested tree lizard, Calotes versicolor (DAUDIN, 1802), is a strong candidate for the status of most widespread non-Gekkonid lizard in the world. GÜNTHER (1864) noted: ”This is one of the most common lizards, extending from Afghanistan over the whole continent [sic] of India to China; it is very common in Ceylon [=Sri Lanka]…” Its present distribution stretches from Oman to the west (LOMAN 1997; SEUFER et al.. 1999) (the following in SAVY (1982) is presumably a reference to Oman: “… more recently the British Museum was sent a specimen from southern Arabia”) right across southern and south-east Asia to Indo-China to the east (STUART 1999), the Maldives (HASEN DIDI 1993), Réunion (PERMALNAÏCK 1993), Mauritius (STAUB 1993), (including Rodrigues (BLANCHARD 2000)), Seychelles (MATYOT 2003) and Florida in the United States (ENGE & KRYSKO 2004). -

Sex Determination in the Garden Lizard, Calotes Versicolor

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/312058; this version posted May 1, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. 1 1 Sex Determination in the garden lizard, Calotes versicolor: Is Environment a 2 Factor? 3 4 5 6 7 8 Priyanka1 and Rajiva Raman1,2 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 1Cytogenetics Laboratory, Department of Zoology, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi-221005, 16 17 2Corresponding Author: E-mail: [email protected] 18 19 Orcid Identifier: 0000-0002-6043-4439 20 21 22 23 Priyanka and R. Raman: Unisex offspring in the lizard C. versicolor 24 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/312058; this version posted May 1, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. 2 25 Abstract 26 The Indian garden lizard, C. versicolor, is known to lack sex chromosomes (Singh, 1974, 27 Ganesh et al 1997). A report from the tropical southern India (Inamdar et al., 2012), claims a 28 TSD (FMFM) mechanism in this species in which the male/female ratio in embryos oscillates 29 within a range of 3-40C. The present study presents results of experiments done in 4 consecutive 30 breeding seasons of C.