Transatlantic Antitrust and IPR Developments, Issue 5/2018 Stanford-Vienna Transatlantic Technology Law Forum 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

On This Date Daily Trivia Happy Birthday! Quote Of

THE SUNDAY, AUGUST 1, 2021 On This Date 1834 – The Emancipation Act was Quote of the Day enacted throughout the British “Study as if you were going to Dominions. Most enslaved people were live forever; live as if you re-designated as “apprentices,” and were going to die tomorrow.” their enslavement was ended in stages over the following six years. ~ Maria Mitchell 1941 – The first Jeep, the army’s little truck that could do anything, was produced. The American Bantam Happy Birthday! Car Company developed the working Maria Mitchell (1818–1889) was the prototype in just 49 days. General first professional female astronomer Dwight D. Eisenhower said that the in the United States. Born in Allies could not have won World Nantucket, Massachusetts, Mitchell War II without it. Because Bantam pursued her interest in astronomy couldn’t meet the army’s production with encouragement from her demands, other companies, including parents and the use of her father’s Ford, also started producing Jeeps. telescope. In October 1847, Mitchell discovered a comet, a feat that brought her international acclaim. The comet became known as “Miss Mitchell’s Comet.” The next year, the pioneering stargazer became the first woman admitted to the Daily Trivia American Academy of Arts and Sciences. The Jeep was probably named after Mitchell went on to Eugene the Jeep, a Popeye comic become a professor strip character known for its of astronomy at magical abilities. Vassar College. ©ActivityConnection.com – The Daily Chronicles (CAN) UNDAY UGUST S , A 1, 2021 Today is Mahjong Day. While some folks think that this Chinese matching game was invented by Confucius, most historians believe that it was not created until the late 19th century, when a popular card game was converted to tiles. -

Films with 2 Or More Persons Nominated in the Same Acting Category

FILMS WITH 2 OR MORE PERSONS NOMINATED IN THE SAME ACTING CATEGORY * Denotes winner [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] 3 NOMINATIONS in same acting category 1935 (8th) ACTOR -- Clark Gable, Charles Laughton, Franchot Tone; Mutiny on the Bounty 1954 (27th) SUP. ACTOR -- Lee J. Cobb, Karl Malden, Rod Steiger; On the Waterfront 1963 (36th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Diane Cilento, Dame Edith Evans, Joyce Redman; Tom Jones 1972 (45th) SUP. ACTOR -- James Caan, Robert Duvall, Al Pacino; The Godfather 1974 (47th) SUP. ACTOR -- *Robert De Niro, Michael V. Gazzo, Lee Strasberg; The Godfather Part II 2 NOMINATIONS in same acting category 1939 (12th) SUP. ACTOR -- Harry Carey, Claude Rains; Mr. Smith Goes to Washington SUP. ACTRESS -- Olivia de Havilland, *Hattie McDaniel; Gone with the Wind 1941 (14th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Patricia Collinge, Teresa Wright; The Little Foxes 1942 (15th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Dame May Whitty, *Teresa Wright; Mrs. Miniver 1943 (16th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Gladys Cooper, Anne Revere; The Song of Bernadette 1944 (17th) ACTOR -- *Bing Crosby, Barry Fitzgerald; Going My Way 1945 (18th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Eve Arden, Ann Blyth; Mildred Pierce 1947 (20th) SUP. ACTRESS -- *Celeste Holm, Anne Revere; Gentleman's Agreement 1948 (21st) SUP. ACTRESS -- Barbara Bel Geddes, Ellen Corby; I Remember Mama 1949 (22nd) SUP. ACTRESS -- Ethel Barrymore, Ethel Waters; Pinky SUP. ACTRESS -- Celeste Holm, Elsa Lanchester; Come to the Stable 1950 (23rd) ACTRESS -- Anne Baxter, Bette Davis; All about Eve SUP. ACTRESS -- Celeste Holm, Thelma Ritter; All about Eve 1951 (24th) SUP. ACTOR -- Leo Genn, Peter Ustinov; Quo Vadis 1953 (26th) ACTOR -- Montgomery Clift, Burt Lancaster; From Here to Eternity SUP. -

P20 Layout 1

20 Friday Lifestyle | Movies Friday, January 5, 2018 Cate Blanchett to head Cannes festival jury ate Blanchett, the double Oscar-winning actress leading a Hollywood campaign to tackle sexual harassment in the Cworkplace, will head the jury at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, organizers said yesterday. Australian Blanchett, 48, who helped launch the “Time’s Up” initiative this week following a string of sexual assault accusations against prominent men in the film industry, will become the 12th woman to lead the prestigious panel at Cannes, which kicks off on May 8. “We’re very pleased to welcome a rare and unique artist with talent and conviction,” Cannes president Pierre Lescure and del- egate general Thierry Fremaux said in a joint statement. “Our conversations this autumn convince us she will be a committed president, and a passionate and generous spectator.” The choice of Blanchett, who was named best actress at the 2014 Academy Awards for her role in Woody Allen’s “Blue Jasmine”, will be seen as politically charged after a year in which the sexual harassment scandal surrounding Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein sparked a deluge of allegations against powerful men in entertainment, politics and the media. Any male who thinks it’s his prerogative to sexually This combination of pictures created yesterday shows (from top left) US actress and president of the jury of 71th Cannes Festival Cate Blanchett on April 11, 2017, New Zealander director and president of the 67th Cannes Festival Jane Campion on May 13, 2014, French intimidate or -

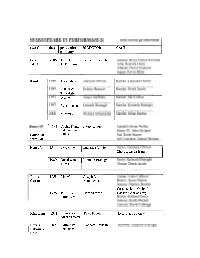

SHAKESPEARE in PERFORMANCE Some Screen Productions

SHAKESPEARE IN PERFORMANCE some screen productions PLAY date production DIRECTOR CAST company As You 2006 BBC Films / Kenneth Branagh Rosalind: Bryce Dallas Howard Like It HBO Films Celia: Romola Gerai Orlando: David Oyelewo Jaques: Kevin Kline Hamlet 1948 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Hamlet: Laurence Olivier 1980 BBC TVI Rodney Bennett Hamlet: Derek Jacobi Time-Life 1991 Warner Franco ~effirelli Hamlet: Mel Gibson 1997 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Hamlet: Kenneth Branagh 2000 Miramax Michael Almereyda Hamlet: Ethan Hawke 1965 Alpine Films, Orson Welles Falstaff: Orson Welles Intemacional Henry IV: John Gielgud Chimes at Films Hal: Keith Baxter Midni~ht Doll Tearsheet: Jeanne Moreau Henry V 1944 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Henry: Laurence Olivier Chorus: Leslie Banks 1989 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Henry: Kenneth Branagh Films Chorus: Derek Jacobi Julius 1953 MGM Joseph L Caesar: Louis Calhern Caesar Manluewicz Brutus: James Mason Antony: Marlon Brando ~assiis:John Gielgud 1978 BBC TV I Herbert Wise Caesar: Charles Gray Time-Life Brutus: kchard ~asco Antony: Keith Michell Cassius: David Collings King Lear 1971 Filmways I Peter Brook Lear: Paul Scofield AtheneILatenla Love's 2000 Miramax Kenneth Branagh Berowne: Kenneth Branagh Labour's and others Lost Macbeth 1948 Republic Orson Welles Macbeth: Orson Welles Lady Macbeth: Jeanette Nolan 1971 Playboy / Roman Polanslu Macbe th: Jon Finch Columbia Lady Macbeth: Francesca Annis 1998 Granada TV 1 Michael Bogdanov Macbeth: Sean Pertwee Channel 4 TV Lady Macbeth: Greta Scacchi 2000 RSC/ Gregory -

Bamcinématek Presents Vengeance Is Hers, a 20-Film Showcase of Some of Cinema’S Most Unforgettable Heroines and Anti-Heroines, Feb 7—18

BAMcinématek presents Vengeance is Hers, a 20-film showcase of some of cinema’s most unforgettable heroines and anti-heroines, Feb 7—18 Includes BAMcinématek’s ninth annual Valentine’s Day Dinner & a Movie, with a screening of The Lady Eve and dinner at BAMcafé The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Brooklyn, NY/Jan 10, 2014—From Friday, February 7 through Tuesday, February 18, BAMcinématek presents Vengeance is Hers. From screwball proto-feminism to witchy gothic horror to cerebral auteurist classics, this 20-film series gathers some of cinema’s most unforgettable heroines and anti-heroines as they seize control and take no prisoners. Seen through the eyes of some of the world’s greatest directors, including female filmmakers such as Chantal Akerman and Kathryn Bigelow, these films explore the full gamut of cinematic retribution in all its thrilling, unnerving dimensions. Vengeance is Hers is curated by Nellie Killian of BAMcinématek and Thomas Beard of Light Industry. Opening the series on Friday, February 7 is Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Medea (1969), a film adaptation of the Euripides tragedy which follows the eponymous sorceress on a vicious crusade for revenge. Starring legendary opera singer Maria Callas in her first and only film role, Medea marks the final entry in Pasolini’s “Mythical Cycle” which also includes Oedipus Rex (1967), Teorema (1968), and Porcile (1969). “Brilliant and brutal” (Vincent Canby, The New York Times), Medea kicks off this series showcasing international films from a variety of genres and creating an alternate history to the clichéd images of avenging women. -

Queering the Shakespeare Film: Gender Trouble, Gay Spectatorship and Male Homoeroticism

Guy Patricia, Anthony. "INDEX." Queering the Shakespeare Film: Gender Trouble, Gay Spectatorship and Male Homoeroticism. London: Bloomsbury Arden Shakespeare, 2017. 259– 292. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 14:06 UTC. Copyright © Anthony Guy Patricia 2017. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. INDEX a word and a blow (William all-male (sauna) xxiv, 74–5, 87, Shakespeare’s Romeo + 97, 185, 196–7, 200–1, Juliet) 115 219 abnormal/ity 8, 45, 202 Amazon/ian/s 3, 6, 32, 225 Achilles 117 n.25 active 58, 60, 63, 66 America/n xiv–xv, xvii, xxi, 1, adaptation/s xx–xxi, xxvii, 2, 73, 90, 190, 192, 197, 4, 9, 25, 30, 37, 43, 54, 201, 206, 214, 215, 221 56, 68, 82, 84–5, 90, n.8, 222 n.2, 230 n.10, 109, 138, 174, 182, 190, 237 n.33, 245 n.39, 230 n.5, 237 n.29, 253 246 n.1, 247, 249, Adelman, Janet 140, 240 n.9, 250 249 anachronism 68, 115, 186 Adler, Renata 55, 216, 232 anal penetration 63 n.39, 249 anality 30, 63, 66–7, 244 n.12, adult/child eroticism 29–30 256 adulterous 28 anal-retentive 186 adultery 188, 209–10 anatomizes 199 Adventures of Priscilla, Queen Ancient Assyria 50 of the Desert, The (Film, Anderegg, Michael 190 dir. Stephan Elliot, 1994) androgynous 161 110 Anger, Kenneth 226 n.36 affection/s/ate 36, 56, 70–1, 81, Anglophone xxii, 28, 219 113, 142, 144, 148, 151, anthropomorphic 21 165, 171, -

Sexism and the Academy Awards

Tripodos, number 48 | 2020 | 85-102 Rebut / Received: 28/03/20 ISSN: 1138-3305 Acceptat / Accepted: 30/06/20 85 Oscar Is a Man: Sexism and the Academy Awards Kenneth Grout Owen Eagan Emerson College (USA) TRIPODOS 2020 | 48 This study analyzes the implicit bias of an to be nominated for a supporting the Academy Awards and Oscar’s his- performance in a Best Picture winner. toric lack of gender equity. While there This research considers these factors, are awards for Best Actor and Actress, identifies potential reasons for them, a comparative analysis of these awards and draws conclusions regarding the and the Best Picture prize reveals that decades of gender bias in the Academy a man is more than twice as likely as a Awards. Further, this study investigates woman to receive an Oscar for leading the dissolution of the Hollywood stu- work in a Best Picture. A man is also dio system and how, though brought nearly twice as likely to be nominated on in part by two of the film industry’s as a leading performer in a Best Pic- leading ladies, the crumbling of that ture winner. Supporting women in Best system ultimately hurt the industry’s Pictures fare a bit better with actual women more than its men. trophies, but, when considering nom- inations, a man is still more than one- Keywords: Oscars, Academy Awards, and-a-half times as likely as a wom- sexism, gender inequity, Best Picture. he Academy Awards have been given out annually for 92 years to, among others, the top actor and actress as voted on by the members of the film T academy. -

MICHAEL CURTIZ: from HUNGARY to HOLLYWOOD Release

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release November 1992 MICHAEL CURTIZ: FROM HUNGARY TO HOLLYWOOD November 27, 1992 - January 23, 1993 A survey of more than fifty films by Michael Curtiz (1888-1962), one of cinema's most prolific directors from the studio era, opens on November 27, 1992, at The Museum of Modern Art. As Warner Bros, house director in the 1930s and 1940s, Curtiz symbolizes the crispness and energy that distinguished the Warners' style. On view through January 23, 1993, MICHAEL CURTIZ: FROM HUNGARY TO HOLLYWOOD explores the consistent quality and versatility of the filmmaker's work. The Hungarian-born Curtiz mastered virtually all genres and, during his twenty-seven-year career at Warner Bros., made every type of film from westerns and musicals to social dramas and comedies. A strong director of actors, he made stars of such disparate types as Errol Flynn, John Garfield, and Doris Day, and earned an Academy Award and a renewed career for Joan Crawford in Mildred Pierce (1945). Many of his films were popular critical and financial successes. Curtiz possessed an acute narrative sense, displayed in such remarkable films included in the exhibition as The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), with Flynn and Olivia de Havilland; Casablanca (1942), for which Curtiz received an Academy Award for Best Director; Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942), the musical which won James Cagney an Academy Award; Mildred Pierce, the film noir portrait of an imperfect American family; Young Man with a Horn (1950), starring Kirk - more - 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019-5498 Tel: 212-708-9400 Cable: MODERNART Telex: 62370 MODART 2 Douglas as an obsessed jazz trumpeter and inspired by Bix Beiderbecke's life; and The Breaking Point (1950), based on Ernest Hemingway's To Have and Have Not, His early successes -- Cabin in the Cotton (1932), a melodrama about sharecroppers, and The Mystery of the Max Museum (1933), an early all-color horror film -- are also included in the exhibition. -

Sample Pages to Cutting Edge Upper Intermediate Teacher's Book

CONTENTS TEACHER’S RESOURCE BOOK Introduction Students’ Book contents 4 Message from the authors 9 Overview of components 10 The Students’ Book 12 The support components 16 Course rationale 18 Teaching tips 20 Teacher’spages notes Index 27 Units 1–12 28 TEACHER’S RESOURCE DISC Extra Resources Sample• Class audio scripts • Video scripts • Photocopiable worksheets with instructions • Photocopiable worksheets index Tests • Progress tests • Mid-course test • End of course test • Test audio • Test audio script • Downloadable test audio • Test answer key 3 A02_CE_TRB_TRB_UINGLB_6834_FM.indd 3 10/09/2013 13:49 STUDENTS’ BOOK CONTENTS pages Sample 4 Study, Practice & Remember page 131, Audio scripts page 167, Irregular verb list page 179 A02_CE_TRB_TRB_UINGLB_6834_FM.indd 4 10/09/2013 13:49 pages Sample 5 A02_CE_TRB_TRB_UINGLB_6834_FM.indd 5 10/09/2013 13:49 STUDENTS’ BOOK CONTENTS pages Sample 6 Study, Practice & Remember page 131, Audio scripts page 167, Irregular verb list page 179 A02_CE_TRB_TRB_UINGLB_6834_FM.indd 6 10/09/2013 13:49 pages Sample 7 A02_CE_TRB_TRB_UINGLB_6834_FM.indd 7 10/09/2013 13:49 01 GETTING ON 2a 1.1 Explain that students are going to listen to six people talking OVERVIEW about important things in their lives. Tell students not to worry if PAGES 6–7 they don’t understand every word and clarify that they only have Speaking and listening: Your past and present to match each speaker to one of the ideas in exercise 1a, and that they’ll have a chance to listen again for more detail afterwards. Play Grammar: Past and present verb forms the recording and do the first as an example with them. -

The Careers of Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas As Referenced in Literature a Study in Film Perception

The Careers of Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas as Referenced in Literature A Study in Film Perception Henryk Hoffmann Series in Cinema and Culture Copyright © 2020 Henryk Hoffmann. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Cinema and Culture Library of Congress Control Number: 2020942585 ISBN: 978-1-64889-036-9 Cover design by Vernon Press using elements designed by Freepik and PublicDomainPictures from Pixabay. Selections from Getting Garbo: A Novel of Hollywood Noir , copyright 2004 by Jerry Ludwig, used by permission of Sourcebooks. Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. To the youngest members of the family— Zuzanna Maria, Ella Louise, Tymon Oskar and Graham Joseph— with utmost admiration, unconditional love, great expectations and best wishes Table of contents List of Figures vii Introduction ix PART ONE.