North Korea's Illicit Cyber Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dprk As an Example of the Potential Utility of Internet Sanctions

\\server05\productn\B\BIN\25-1\BIN104.txt unknown Seq: 1 31-MAR-08 10:18 USING INTERNET “BORDERS” TO COERCE OR PUNISH: THE DPRK AS AN EXAMPLE OF THE POTENTIAL UTILITY OF INTERNET SANCTIONS BENJAMIN BROCKMAN-HAW E * INTRODUCTION ................................................... 163 R I. BACKGROUND INFORMATION .............................. 166 R A. Escalation ............................................. 167 R B. The Internet in North Korea ........................... 173 R II. SANCTIONS ................................................ 181 R A. General Information ................................... 182 R B. Telecommunications Sanctions Already Considered .... 184 R C. Multilateral Sanctions In Place Against the DPRK ..... 187 R III. THE UTILITY OF INTERNET SANCTIONS .................... 187 R A. Obtaining a desired result through the imposition of Internet sanctions ...................................... 187 R B. The Benefits and Costs of Imposing Internet Sanctions . 198 R C. General Concerns Associated with the Use of Internet Sanctions .............................................. 200 R 1. International Human Rights ....................... 200 R 2. Internet sanctions could harm regime opponents . 203 R 3. Internet sanctions could impair the ability of UN operations and NGO’s to function within the target country ..................................... 204 R IV. CONCLUSION .............................................. 205 R INTRODUCTION Speech is civilization itself. The word. preserves contact—it is silence which isolates. - Thomas Mann1 * J.D. Candidate 2008, Boston University School of Law. This article is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Robert Brockman, a man who surveyed this new world with the eyes of an old soul. 1 THOMAS MANN, THE MAGIC MOUNTAIN (1924) quoted in CHARLES R. BURGER & JAMES J. BRADAC, LANGUAGE AND SOCIAL KNOWLEDGE 112 (Edward Arnold Publishers Ltd. 1982). 163 \\server05\productn\B\BIN\25-1\BIN104.txt unknown Seq: 2 31-MAR-08 10:18 164 BOSTON UNIVERSITY INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL [Vol. -

1:14-Mc-00648-UNA Document 7 Filed 07/29/14 Page 1 of 3

Case 1:14-mc-00648-UNA Document 7 Filed 07/29/14 Page 1 of 3 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Ruth Calderon-Cardona, et al., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) CIVIL ACTION NO. 14-mc-648 ) Democratic People's Republic of Korea, et ) HEARING REQUEST al., ) ) Defendants. ) ) ) INTERNET CORPORATION FOR ASSIGNED NAME AND NUMBERS’ MOTION TO QUASH WRIT OF ATTACHMENT The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (“ICANN”), a non-party, by counsel, respectfully moves this Court to quash the Writ of Attachment on Judgment Other Than Wages, Salary And Commissions (“Writ of Attachment”) issued by Plaintiffs in the above- entitled action, for the reasons set forth in ICANN’s accompanying Memorandum.1 Furthermore, ICANN, in accordance with Local Civil Rule 78.1, requests that an oral hearing be scheduled to inform the Court’s ruling on the Motion. 1 Plaintiffs issued to ICANN, and ICANN is moving to quash, writs of attachment in seven actions: (1) Rubin, et al. v. Islamic Republic of Iran, et al., Case No. 01-1655-RMU; (2) Haim, et al. v. Islamic Republic of Iran, et al., Case No. 02-1811-RCL; (3) Haim, et al. v. Islamic Republic of Iran, et al., Case No. 08-520-RCL; (4) Stern, et al. v. Islamic Republic of Iran, et al., Case No. 00-2602-RCL; (5) Weinstein, et al. v. Islamic Republic of Iran, et al., Case No. 00- 2601-RCL; (6) Wyatt, et al. v. Syrian Arab Republic, et al., Case No. 08-502-RCL; and (7) Calderon-Cardona, et al. -

Generic Top-Level Domains (Gtld)

An essential pillar for any business is its brand. Brand presence on the Web is a key factor in a business appearing in Internet searches and being found by existing and prospective customers. For small business owners, the essential ingredients for building a strong brand are: o A memorable business name o brand identity elements: o domain name o logo o email address o business card o social Web presence ( Linkedin, Facebook, Twitter, et Generic Top-Level Domains (gTLD) The following table represents the generic top-level domains (i.e. including .com, .org, etc). Domain Purpose / Sponsoring Organization Generic top-level domain .COM VeriSign Global Registry Services Generic top-level domain .INFO Afilias Limited Generic top-level domain .NET VeriSign Global Registry Services Generic top-level domain .ORG Public Interest Registry (PIR) Generic-Restricted Top-Level Domains Generic-restricted top-level domain names are similar to the generic top-level domains, only eligibility is intended to be restricted and ascertained more stringently. Domain Purpose / Sponsoring Organization Restricted for Business .BIZ NeuStar, Inc. Reserved for individuals .NAME The Global Name Registry Ltd. Restricted to credentialed professionals and related entities .PRO Registry Services Corporation dba RegistryPro Sponsored Top-Level Domains (sTLD) These domains are proposed and sponsored by private agencies or organizations that establish and enforce rules restricting the eligibility to use the TLD. IANA also groups sTLDs with the generic top-level domains. Domain Purpose / Sponsoring Organization Reserved for members of the air-transport industry .AERO Societe Internationale de Telecommunications Aeronautique S.C. (SITA SC) Restricted to the Pan-Asia and Asia Pacific community .ASIA DotAsia Organization Ltd. -

VBI Vulnerabilities Portfolio

VBI Vulnerabilities Portfolio October 28, 2013 <[email protected]> http://www.vulnbroker.com/ CONFIDENTIAL VBI Vulnerabilities Portfolio Contents 1 Foreword 6 1.1 Document Formatting.................................... 6 1.2 Properties and Definitions.................................. 6 1.2.1 Vulnerability Properties............................ 6 1.2.2 Vulnerability Test Matrix........................... 8 1.2.3 Exploit Properties............................... 8 2 Adobe Systems Incorporated 12 2.1 Flash Player......................................... 12 VBI-12-033 Adobe Flash Player Client-side Remote Code Execution........... 12 2.2 Photoshop CS6....................................... 15 VBI-13-011 Adobe Photoshop CS6 Client-side Remote Code Execution......... 15 3 Apple, Inc. 17 3.1 iOS.............................................. 17 VBI-12-036 Apple iOS Remote Forced Access-Point Association............. 17 VBI-12-037 Apple iOS Remote Forced Firmware Update Avoidance........... 18 4 ASUS 21 4.1 BIOS Device Driver..................................... 21 VBI-13-015 ASUS BIOS Device Driver Local Privilege Escalation............ 22 5 AVAST Software a.s. 24 5.1 avast! Anti-Virus...................................... 24 October 28, 2013 CONFIDENTIAL Page 1 of 120 VBI Vulnerabilities Portfolio VBI-13-005 avast! Local Information Disclosure..................... 24 VBI-13-010 avast! Anti-Virus Local Privilege Escalation................. 26 6 Barracuda Networks, Inc. 28 6.1 Web Filter.......................................... 28 VBI-13-000 -

North Korea Security Briefing

Companion report HP Security Briefing Episode 16, August 2014 Profiling an enigma: The mystery of North Korea’s cyber threat landscape HP Security Research Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Research roadblocks ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Ideological and political context .................................................................................................................... 5 Juche and Songun ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Tension and change on the Korean Peninsula .......................................................................................... 8 North Korean cyber capabilities and limitations ......................................................................................... 10 North Korean infrastructure.................................................................................................................... 10 An analysis of developments in North Korean cyberspace since 2010 .................................................. 14 North Korean cyber war and intelligence structure ................................................................................ 21 North Korean cyber and intelligence organizational chart .................................................................... -

North Korean Strategic Strategy: Combining Conventional Warfare with The

NORTH KOREAN STRATEGIC STRATEGY: COMBINING CONVENTIONAL WARFARE WITH THE ASYMMETRICAL EFFECTS OF CYBER WARFARE By Jennifer J. Erlendson A Capstone Project Submitted to the Faculty of Utica College March, 2013 In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Science – Cybersecurity – Intelligence and Forensics © Copyright 2013 by Jennifer J. Erlendson All Rights Reserved ii Abstract Emerging technologies play a huge role in security imbalances between nation states. Therefore, combining the asymmetrical effects of cyberattacks with conventional warfare can be a force multiplier; targeting critical infrastructure, public services, and communication systems. Cyber warfare is a relatively inexpensive capability which can even the playing field between nations. Because of the difficulty of assessing attribution, it provides plausible deniability for the attacker. Kim Jong Il (KJI) studied the 2003 Gulf War operational successes of the United States (U.S.) and the United Kingdom (U.K.), noting the importance of high-tech weapons and information superiority. KJI realized the only way to compete with the U.S.’technology and information superiority was through asymmetric warfare. During the years that followed, the U.S. continued to strengthen its conventional warfare capabilities and expand its technological dominance, while North Korea (NK) sought an asymmetrical advantage. KJI identified the U.S.’ reliance on information technology as a weakness and determined it could be countered through cyber warfare. Since that time, there have been reports indicating a NK cyber force of 300-3000 soldiers; some of which may be operating out of China. Very little is known about their education, training, or sophistication; however, the Republic of Korea (ROK) has accused NK of carrying out cyber-attacks against the ROK and the U.S since 2004. -

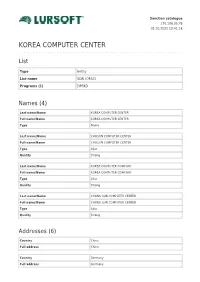

Korea Computer Center

Sanction catalogue 170.106.35.76 02.10.2021 12:41:16 KOREA COMPUTER CENTER List Type Entity List name SDN (OFAC) Programs (1) DPRK3 Names (4) Last name/Name KOREA COMPUTER CENTER Full name/Name KOREA COMPUTER CENTER Type Name Last name/Name CHOSON COMPUTER CENTER Full name/Name CHOSON COMPUTER CENTER Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name KOREA COMPUTER COMPANY Full name/Name KOREA COMPUTER COMPANY Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name CHUNG SUN COMPUTER CENTER Full name/Name CHUNG SUN COMPUTER CENTER Type Alias Quality Strong Addresses (6) Country China Full address China Country Germany Full address Germany Country Syria Full address Syria Country India Full address India Country United Arab Emirates Full address United Arab Emirates City Pyongyang Country North Korea Full address Pyongyang, Korea, North Identification documents (2) Type Secondary sanctions risk:: North Korea Sanctions Regulations, sections 510.201 and 510.210 Type Transactions Prohibited For Persons Owned or Controlled By U.S. Financial Institutions:: North Korea Sanctions Regulations section 510.214 Updated: 02.10.2021. 05:15 The Sanction catalog includes Latvian, United Nations, European Union, United Kingdom and Office of Foreign Assets Control subjects included in sanction list. © Lursoft IT 1997-2021 Lursoft is the re-user of information from the Enterprise Register of Latvia. The user is obliged to observe the Copyright law, Personal Data Processing Law requirements and Terms of Use of the Lursoft system. The user is forbidden to use any automatic systems or equipment (robots) in order to access the system without a written approval from Lursoft. -

The Shadow Sector: North Korea's Information Technology Networks

The Shadow Sector: CNS North Korea’s Information OCCASIONAL PAPER #36 MAY 2018 Technology Networks Andrea Berger, Cameron Trainer, Shea Cotton, and Catherine Dill James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies nonproliferation.org The James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies (CNS) strives to combat the spread of weapons of mass destruction by training the next generation of nonproliferation specialists and disseminating timely information and analysis. CNS at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey is the largest nongovernmental organization in the United States devoted exclusively to research and training on nonproliferation issues. Middlebury Institute for International Studies at Monterey www.miis.edu The Middlebury Institute for International Studies at Monterey provides international professional education in areas of critical importance to a rapidly changing global community, including international policy and management, translation and interpretation, language teaching, sustainable development, and nonproliferation. We prepare students from all over the world to make a meaningful impact in their chosen fields through degree programs characterized by immersive and collaborative learning, and opportunities to acquire and apply practical professional skills. Our students are emerging leaders capable of bridging cultural, organizational, and language divides to produce sustainable, equitable solutions to a variety of global challenges. James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies Monterey Institute -

North Korea Freedomhouse.Org

https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-press/2015/north-korea#.VfGS-KHKgDs.cleanprint North Korea freedomhouse.org North Korea remained one of the most repressive media environments in the world in 2014, as its leader, Kim Jong-un, sustained his efforts to solidify his grip on power. The North Korean media have continued their propaganda efforts to consolidate national unity around Kim Jong-un, who assumed the country’s leadership after the death of his father and predecessor, Kim Jong-il, in December 2011. Freedom of expression in the country gained renewed attention worldwide in 2014 as the regime threatened war on the United States over a satirical Hollywood movie, Interview, about a fictional U.S. Central Intelligence Agency attempt to assassinate Kim. The U.S. government blamed North Korea for a subsequent cyberattack on Sony Pictures Entertainment, which released the film; the cyberattack resulted in numerous leaked e-mails. Legal Environment Although the constitution theoretically guarantees freedom of speech, provisions calling for adherence to a “collective spirit” restrict in practice all reporting that is not sanctioned by the government. Under the penal code, listening to unauthorized foreign broadcasts and possessing dissident publications are considered “crimes against the state” that carry serious punishments, including hard labor, prison sentences, and the death penalty. North Koreans are often interrogated or arrested for speaking critically about the government; they also face arrest for possessing or watching television programs acquired on the black market. Political Environment The one-party regime controls all domestic news outlets, attempts to regulate all communication, and rigorously limits the ability of North Korean people to access outside information. -

VBI Vulnerabilities Portfolio

VBI Vulnerabilities Portfolio March 31, 2014 <[email protected]> http://www.vulnbroker.com/ CONFIDENTIAL VBI Vulnerabilities Portfolio Contents 1 Foreword 7 1.1 Document Formatting.................................... 7 1.2 Properties and Definitions.................................. 7 1.2.1 Vulnerability Properties............................ 7 1.2.2 Vulnerability Test Matrix........................... 9 1.2.3 Asset Deliverables............................... 9 1.2.4 Exploit Properties............................... 10 2 Adobe Systems Incorporated 13 2.1 Adobe Reader........................................ 13 VBI-14-004 Adobe Reader Client-side Remote Code Execution............. 13 2.2 Flash Player......................................... 15 VBI-12-033 Adobe Flash Player Client-side Remote Code Execution........... 15 2.3 Photoshop CS6....................................... 17 VBI-13-011 Adobe Photoshop CS6 Client-side Remote Code Execution......... 18 3 ASUS 20 3.1 BIOS Device Driver..................................... 20 VBI-13-015 ASUS BIOS Device Driver Local Privilege Escalation............ 21 4 AVAST Software a.s. 23 4.1 avast! Anti-Virus...................................... 23 VBI-13-005 avast! Local Information Disclosure..................... 23 March 31, 2014 CONFIDENTIAL Page 1 of 134 VBI Vulnerabilities Portfolio VBI-13-010 avast! Anti-Virus Local Privilege Escalation................. 25 5 Barracuda Networks, Inc. 27 5.1 Web Filter.......................................... 27 VBI-13-000 Barracuda Web Filter Remote Privileged -

North Korea Designations; North Korea Administrative Update; Counter Terrorism Desig

North Korea Designations; North Korea Administrative Update; Counter Terrorism Desig... Page 1 of 32 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Resource Center North Korea Designations; North Korea Administrative Update; Counter Terrorism Designations 10/4/2018 OFFICE OF FOREIGN ASSETS CONTROL Specially Designated Nationals List Update The following individuals have been added to OFAC's SDN List: AL-AMIN, Muhammad 'Abdallah (a.k.a. AL AMEEN, Mohamed Abdullah; a.k.a. AL AMIN, Mohammad; a.k.a. AL AMIN, Muhammad Abdallah; a.k.a. AL AMIN, Muhammed; a.k.a. AL-AMIN, Mohamad; a.k.a. ALAMIN, Mohamed; a.k.a. AMINE, Mohamed Abdalla; a.k.a. EL AMINE, Muhammed), Yusif Mishkhas T: 3 Ibn Sina, Bayrut Marjayoun, Lebanon; Beirut, Lebanon; DOB 11 Jan 1975; POB El Mezraah, Beirut, Lebanon; nationality Lebanon; Additional Sanctions Information - Subject to Secondary Sanctions Pursuant to the Hizballah Financial Sanctions Regulations; Gender Male (individual) [SDGT] (Linked To: TABAJA, Adham Husayn). CULHA, Erhan; DOB 17 Oct 1954; POB Istanbul, Turkey; nationality Turkey; Gender Male; Secondary sanctions risk: North Korea Sanctions Regulations, sections 510.201 and 510.210; Passport U09787534 (Turkey) issued 12 Sep 2014 expires 12 Sep 2024; Personal ID Card 10589535602; General Manager (individual) [DPRK] (Linked To: SIA FALCON INTERNATIONAL GROUP). RI, Song Un, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia; DOB 16 Dec 1955; POB N. Hwanghae, North Korea; nationality Korea, North; Gender Male; Secondary sanctions risk: North Korea Sanctions Regulations, sections 510.201 and 510.210; Passport 836110063 (Korea, North) issued 04 Feb 2016 expires 04 Feb 2021; Economic and Commercial Counsellor at DPRK Embassy in Mongolia (individual) [DPRK2]. -

Mapping Communication Research Concerning North Korea: a Systematic Review (2000–2019)

International Journal of Communication 14(2020), 1308–1330 1932–8036/20200005 Mapping Communication Research Concerning North Korea: A Systematic Review (2000–2019) SOOMIN SEO1 Temple University, USA SEUNGAHN NAH University of Oregon, USA Although North Korea is increasingly in the limelight of international news, a systematic review has yet to offer an accumulated body of knowledge regarding North Korea and its related communication scholarship. This study assesses the current state of research on media and communication in, around, and about North Korea from 2000 to June 2019. It examines a total of 85 research articles published in 57 journals. Overall, it finds an explosion in research after 2009. Findings reveal that research overwhelmingly deals with content analysis of Western media coverage, which indicates a strong influence of Cold War binaries. Findings also show that North Korea’s media environment has been moving toward more openness and better connectivity. Ultimately, this study finds a need for more comparative research to examine not only content, but also audience and producers—to include those inside North Korea, for which innovative, interdisciplinary approaches are called for. Keywords: global media, North Korea, research agenda, systematic review Scholarly interest in North Korea is a relatively new phenomenon. Up until the 1980s, academic and journalistic writings about the country, long known as a “hermit regime,” were largely lacking. There was little interest to begin with, North Korea being a small, Easternmost country among communist countries. It did not help that North Korea had been difficult to access—its government and its people. Since the 1990s, however, major changes in international politics have taken place, with rising tensions surrounding North Korea’s nuclear and military developments, rapprochement between the two Koreas, and Kim Jong-il’s reform drive, as well as mass defection of North Koreans amid growing concerns about the country’s human rights record.