Binaries: Remarks on Chaim N. Saiman's "Halakhah"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life and Impact of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik (Part Two)

The Life and Impact of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik (Part Two) David Jacobowitz Congregation Torah Ohr Boca Raton, Florida January 20, 2020 “Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik (1903-1993) was not only one of the outstanding Talmudists of the twentieth century but also one of its most creative and seminal Jewish thinkers. His stature was such that he was widely known simply as “the Rav” – The Rabbi par excellence. Drawing from a vast reservoir of Jewish and general knowledge, Rabbi Soloveitchik brought Jewish thought and law to bear on the interpretation and assessment of the modern experience. On the one hand, he built bridges between Judaism and the modern world; yet, at the same time, he vigorously upheld the integrity and autonomy of the Jew’s faith commitment.” Dr. David Shatz, Professor of Philosophy, Yeshiva University, Introduction to Lonely Man of Faith 1 The Rav and Religious Zionism Questions: 1. Why was the Rav so firmly anti-Zionist when he came to the US? 2. How did the impact of the Shoah and the birth of Israel cause him to fundamentally change his perspective? 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 “The Rav was arguably the greatest exponent of Religious Zionism in the 20th Century and he traveled a long path to reach that position. He constructed a majestic Religious Zionism built on activism and the passionate desire to seek out God’s guiding hand in the world. -

St. Francis College Career Development Center

St. Francis College Career Development Center TABLE SCHOOL GRADUATE PROGRAMS OFFERED NUMBER St. Francis College Accounting, Psychology, Project Management Certificate Program 1 International Relations, English, Creative Writing, Human Resources, Across the Pond 2 Psychology, Business Management and more Arts & Sciences, Business, Education, Nursing and Public Health, Adelphi University 3 Social Work, Emergency Management, Health Innovation MS Ed Literacy, School Counseling: C.A.S. Mental Health Alfred University Counseling, MA Public Administration, Certificate of Advanced Study 4 in Mental Health Counseling American International College Various 5 Ave Maria School of Law J.D. 6 MS in Child Life, MSED with a variety of specialties including early Bank Street Graduate School of Education Childhood, Special Education and Literacy. MSED/MSW, Education 7 Leadership including in the Arts, Early Childhood, and Mathematics Baruch College - Ziklin School of Business MBA & MS 8 Boston College Lynch Graduate School of Teacher Education, Educational Research, Counseling Psychology 9 Education Brooklyn Law School J.D. and LL.M 10 College of Mount Saint Vincent MS Nursing, MS Education, MBA 11 Page 1 St. Francis College Career Development Center College of Mount Saint Vincent International Development and Service 12 College of Mount Saint Vincent & Concordia MA & MS in International Development and Service 13 University - Portland College of Saint Rose Various 14 College of Staten Island (CUNY) Various 15 Columbia University, Teacher’s College Nursing -

RIETS Application

RABBI ISAAC ELCHANAN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY an affiliate of Yeshiva University 500 West 185 Street, Glueck Suite 632 • New York, NY 10033 (646) 592-4455 • Fax: (646) 592-4060 • [email protected] • www.riets.edu Instructions for Completing Application for Admission 1. Students apply either to the Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik Semikha Program, the Pre-Semikha Program, or the Ludwig Jesselson Kollel Chaverim (Chaver Program) Program. While it is envisioned that most of the students will have attended Yeshiva College, graduates from other college institutions may apply as well, in accordance with the requirements set forth below. a. Requirements for admission to the Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik Semikha Program include: i. A Bachelor’s degree from an accredited college or university. Students with senior status at Yeshiva College or the Sy Syms School of Business may be considered for acceptance to the Semikha program during their senior year of college on an individual basis, based on their length of study in Israel. ii. A satisfactory record in Talmud and Jewish Studies beyond the secondary school level for at least four years. Successful completion of any of the Yeshiva College Undergraduate Torah Studies Programs will automatically count towards fulfillment of this requirement. iii. An entrance examination (bechina) demonstrating proficiency in Talmud. iv. A personal interview. b. Requirements for admission to the Pre-Semikha Program (for those not yet ready to be accepted to the Semikha program) include: i. A Bachelor’s degree from an accredited college or university. ii. An entrance examination (bechina). iii. A personal interview. c. Applicants to the Ludwig Jesselson Kollel Chaverim (Chaver Program) are evaluated on an individual basis. -

The Urology Residency Program of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

THE UROLOGY RESIDENCY PROGRAM OF THE ICAHN SCHOOL OF MEDICINE AT MOUNT SINAI Overview The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Urology Residency Program is an ACGME-accredited program with a training format consisting of one year of preliminary training in general surgery followed by four years of urology. Its home institution is The Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City. The program is currently approved for a complement of four residents per training year, though as a result of a recent merger with our sister program at Mount Sinai Beth Israel, the current enrollment includes four residents in the PGY 2 year, and five in each of PGY’s 3 through 5. The program curriculum assures that over the course of training, every resident receives ample experience and didactic grounding in all of the core domains and techniques of urology while acquiring the professional skills and competencies that are characteristic of excellent physicians. Each of the 19 rotations that comprise the curriculum include experience in both in-patient and out-patient treatment settings, with selected rotations offering concentrated experience in areas such as pediatric urology, urodynamics, endourology, female urology, infertility and oncology. An overarching schedule of conferences (led by faculty, fellow residents and guest lecturers), collaborative research projects and support for participation in professional organizations and special programs knit the residents’ clinical experience into the fabric of current urologic scholarship. Our home and affiliated institutions offer an immersive experience in three distinct health care delivery models: the tertiary care academic medical center, the community hospital and the municipal hospital system. -

1950S 1960S 1970S 1980S 1990S

CLASS Your news is our news! ClassNotes Dr. Stanford “2009 New York Super Lawyers”, pub- is where YU celebrates the mile- Goldman ’61YC, lished in The New York Times Magazine, ’65E was awarded listed Ira Lawrence Herman ’79YC in 1980s stones and accomplishments of our honorary member- the top 5 percent of lawyers in the New Dr. Allan Barsky ’88W published a alumni. In this section, you can catch ship to the Royal York metro area. textbook, Ethics and Values in Social up on everything your classmates Belgian Radiological Work: An Integrated Approach for a have been up to over the years, from Society (RBRS) Comprehensive Curriculum (Oxford for outstanding THE AWARD GOES TO… marriages and births to professional University Press, 2010). achievements in uroradiology. Dr. Michael and personal achievements. You can Aizenman ’75BS Notes submit your class note by e-mailing Chana Henkin received the [email protected] with the subject line ’64YUHS, ’68S, 2010 Dannie PRESIDENT OBAMA TAPS “ClassNotes,” by mailing the form ’76BR was Heineman Prize ALUMNUS FOR COUNCIL included on the back of this page, mentioned in the for Mathematical or by visiting www.yu.edu/alumni. Jerusalem Post Physics from (October 22, 2009) the American Physical Society. We hope that you enjoy reading about for her outstand- Aizenman received the award for your fellow alumni and friends, and ing achievements his “development of the random we look forward to hearing about in promoting female scholarship. She current approach to correlations your achievements. founded Nishmat, an elite school for which has had an impact on a wide Israeli and American women that variety of problems, especially his emphasizes beit midrash havruta study rigorous non-perturbative proof of of Talmud. -

Combined/Joint Degree Programs and Articulation Agreements* 1

Yeshiva University 215 Lexington Avenue, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10016 STERN COLLEGE FOR WOMEN Phone: (646) 592-4170 | Fax: (212) 340-7788 Academic Advisement Center [email protected] Advisers Mrs. Miriam Schechter, Director . [email protected] Dr. Jill Katz . [email protected] Dr. Rochelle Kohn . [email protected] Combined/Joint Degree Programs and Articulation Agreements* 1. Business Administration 6. Nutrition* 11. Physician Assistant 2. Engineering 7. Occupational Therapy 12. Podiatry 3. Jewish Education 8. Optometry 13. Teaching Math & Science* 4. Jewish Studies 9. Physical Therapy (NYMC)* 5. Nursing 10. Physical Therapy (Rutgers) Below are the basic elements of each program. Detailed information is available from the academic advisors. These programs are competitive, and final admission decisions are made by the cooperating institution. 1. Business Administration - B.A./M.B.A. Yeshiva University and Bar Ilan University agree to admit qualified students simultaneously to a YU undergraduate program and a new M.B.A. program at Bar Ilan. The 13-month M.B.A. program will be taught in English at Bar Ilan in Israel. Once admitted to the program, students will have to maintain at least a B average. 2. Engineering - B.A./B.E./B.S. or B.A./M.S. Yeshiva University offers combined plans in engineering with Columbia University School of Engineering and Applied Science (CU) as well as with the State University of New York at Stony Brook College of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SBU) Under the BA/BS plan with Columbia, a student who maintains a 3.3 average overall as well as in Program-required courses (with no grade lower than a B in courses required by Columbia), and receives the recommendation of the pre-engineering adviser is admitted to Columbia University School of Engineering and Applied Science. -

J. David Bleich, Ph.D., Dr. Iuris Rosh Yeshivah (Professor of Talmud)

J. David Bleich, Ph.D., Dr. Iuris Rosh Yeshivah (Professor of Talmud) and Rosh Kollel, Kollel le-Hora'ah (Director, Postgraduate Institute for Jurisprudence and Family Law), Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary; Professor of Law, Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law; Tenzer Professor of Jewish Law and Ethics, Yeshiva University; Rabbi, The Yorkville Synagogue, New York City; has taught at the University of Pennsylvania, Hunter College, Rutgers University and Bar Ilan University; ordained, Mesivta Torah Vodaath; Graduate Talmudic Studies, Beth Medrash Elyon, Monsey, N.Y. and Kollel Kodshim of Yeshiva Chofetz Chaim of Radun; Yadin Yadin ordination; Woodrow Wilson Fellow; Post-Doctoral Fellow, Hastings Institute for Ethics, Society and the Life Sciences; Visiting Scholar, Oxford Center for Post-Graduate Hebrew Studies; Editor, Halakhah Department, Tradition; Contributing Editor, Sh'ma; Associate Editor, Cancer Investigation; Past Chairman, Committee on Medical Ethics, Federation of Jewish Philanthropies; Founding Chairman, Section on Jewish Law, Association of American Law Schools; Contributor, Encyclopedia of Bioethics; Fellow, Academy of Jewish Philosophy; Member, New York State Task Force on Life and the Law; Past Chairman, Committee on Law, Rabbinical Alliance of America; Member, Executive Board, COLPA (National Jewish Commission on Law and Public Affairs); Member, Board of Directors, Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America; Member, National Academic Advisory Council of the Academy for Jewish Studies Without Walls; Member, -

Frank J. Macchiarola Biography

FRANK J. MACCHIAROLA BIOGRAPHY Chancellor, St. Francis College B.A., 1962, L.H.D., 1981, St. Francis College; LL.B., 1965, Ph.D., 1970, Columbia University; LL.D., 1983, Dominican College; L.H.D., 1983, College of Staten Island of the City University of New York; LL.D., 1983, Manhattan College; LL.D., 1999, Molloy College; L.H.D., 1999, Saint Joseph’s College; L.H.D., 2009, Fordham University. Frank J. Macchiarola, Ph.D., whose interests and expertise span the legal, academic, religious, executive management and public service areas, joined St. Francis College, his alma mater, as president in July 1996. He served in that role until 2008 when he stepped down to become the Chancellor of St. Francis College. Prior to his service at his alma mater, Dr. Macchiarola served as dean and professor of law at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law of Yeshiva University (1991-96), where he taught Legal Process, Contracts and Legal Writing. He also served as professor of business in Columbia University's Graduate School of Business with teaching and research interests in business law, government regulation of business and nonprofit management (1988-91). He also served as chair of the advisory committee of the Columbia Business School Community Collaboration and served on doctoral panels in political science and education. A faculty member at the City University of New York from 1964-85, he served at City College, Baruch College, and City University Graduate School, leaving as professor of political science on the doctoral faculty. He served as vice president of the City University Graduate School and as director of the Top 40 Program of the CUNY Urban Academy for Management. -

Telling It Like It Is: YU Alumni in Journalism

YESHIVA UNIVERSITY ALUMNITODAYFALL 2013 Telling It Like It Is: YU Alumni In Journalism Ari Goldman ’71YC Shayndi Raice ’05S, ’07BR Gary Rosenblatt ’68YC Avital Chizhik ’12S he British playwright Tom Stoppard once said, “I still believe that if “I agree with Rabbi Chanina, who says in the Talmud that he learned the your aim is to change the world, journalism is a more immediate short- most from his students,” said Goldman. “My students have opened my eyes to Tterm weapon.” Yeshiva University is proud to have many alumni who so many new ideas and ways of thinking. What I try to teach my students is believe that the pen is mightier than the sword and who are changing the not explicitly in the Talmud, but it is certainly rooted there. I tell them to world through their written words. write about other people the way they would like to be written about—with respect, knowledge and sensitivity.” ARI GOLDMAN ’71YC: RELIGION AND REPORTING INTRINSICALLY TIED Goldman is excited whenever a YU graduate shows up in his classes at The decision to attend YU was not a difficult one for Ari Goldman, originally Columbia, and he encourages current students to truly consider a journalism from Hartford, CT. “It was the only school I applied to,” he said. His father, career if they maintain an interest in the field. “Don’t be afraid; take chances Rabbi Marvin Goldman, was a 1944 YC graduate; an uncle, Rabbi Israel and do something you love,” he said. “Many people told me that I shouldn’t be Miller, served as the senior vice president of YU; and another uncle, Rabbi a journalist, and said that I couldn’t be observant, that I couldn’t make a living. -

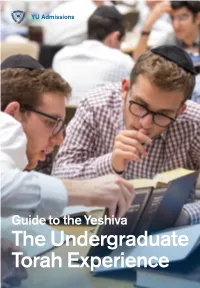

Guide to the Yeshiva

YU Admissions Guide to the Yeshiva The Undergraduate Torah Experience Welcome to Yeshiva! Our Yeshiva has a long and profound history and legacy of Torah scholarship, Jewish values, and spiritual aspirations. Grounded in the world-view of Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik and guided today by our world-renowned Roshei Yeshiva, we prepare each student on his personal path to greatness. We have assembled in one Yeshiva an unparalleled group of warm Rebbeim, insightful Mashgichim, and helpful support staff to enable you to have an uplifting and enriching Torah experience—ranging from beginner to advanced 3 Yeshiva Program/ levels. Beyond the Beit Midrash and classroom Mazer School of Talmudic Studies (MYP) learning, we provide programming, shabbatonim, 4 Isaac Breuer College of and extracurricular events with Rebbeim, often in Hebraic Studies (IBC) their homes. As you decide where you will spend 7 The James Striar School the next stage of your life’s journey, we hope that (JSS) you will join us here in Yeshiva and take full 8 Irving I. Stone Beit Midrash advantage of all that we have to offer you here. Program (SBMP) 10 Masmidim Program With Torah Blessings, 13 BA/Semicha Program 14 Support Staff Administration/ Mashgichim/ Madrichim/ Shiur Assistants 16 Annual Programming Rabbi Dr. Ari Berman, Rabbi Dr. Yosef Kalinsky, President Dean ROSHEI YESHIVA AND REBBEIM Rabbi Elchanan Rabbi Eliyahu Rabbi Mordechai Rabbi Yitzchak Rabbi Daniel Rabbi Meir Adler Ben-Haim Benhaim Cohen Feldman Goldwicht Rabbi David Hirsch Rabbi Dr. Dovid Rabbi Aharon Kahn Rabbi Eliakim Rabbi Yaakov Rabbi Hershel Horwitz Koenigsberg Neuburger Reichman Rabbi Dr. Michael Rabbi Avi Sarfaty Rabbi Hershel Rabbi Eliahu Rabbi Baruch Rabbi Zvi Rosensweig Schachter Baruch Shulman Simon Sobolofsky Rabbi Daniel Stein Rabbi Dr. -

YU Branding Guide

Core Identity Style Guide Contents Introduction i Using Manual ii Section 1 Identity and Elements 1 Section 2 Stationery 25 Section 3 Internal Forms 50 Section 4 Marketing Materials 56 Introduction The purpose of this manual is to ensure the consistent use and application of the Yeshiva University identity through form and material. The Yeshiva University identity employs various graphic devices and design elements. In conjunction with appropriated rules for their application, these elements and devices form a public image. i Using Manual This manual is divided into several categories that address design elements and their application. It begins by outlining the fundamental elements of the identity itself. Once the elements and their rules of application are established, the manual illustrates variations and extensions of the primary identity. The variations and extensions are then supported in the following section showing the appropriate application. Each element and application is illustrated in three manners: establishment of the element or application, rules for use and demonstrations of violation of use. ii Identity and Elements The Yeshiva University identity is comprised Typography 1 1 of two fundamental elements: type and color. Typography Use Rules 1.1a Typography Examples 1.1b These elements are expressed through three Typography Violations 1.1c core devices: a shield mark, a logotype and a lockup of shield mark combined with the logotype to construct the primary identity. Identity Color 1 2 Identity Color Violations 1.2a As Yeshiva University encompasses a wide variety of constituents with varying levels of Shield Mark 1 3 hierarchy, rules have been established to Shield Mark Violations 1.3a identify the varying constituents and their relative hierarchy. -

Open House and Israel Fair Sunday, November 11, 2018 Program Schedule

CLUB FAIR DIRECTORY 215 Lexington Avenue (corner of East 33rd Street), 5th floor Active Minds College Republicans Sephardic Club Accounting Society Data Analytics Sinai Scholars Ahavas Chesed Hisoriri START: Students, Teachers and Athletics International Club Researchers Teach Beit Midrash Committee Israel Club UAID: United Against Inequities in Disease Business and Medical Society SEC: Shabbat Enhancement College Democrats Committee ISRAEL FAIR DIRECTORY These schools participate in the S. Daniel Abraham Israel Program Darchei Binah ...................919 Midreshet AMIT. .407 Stella K. Abraham Beit Midrash Emunah V’Omanut ............. 806 Midreshet Eshel .................601 for Women Migdal Oz Israel Experience Midreshet HaRova ..............101 of Yeshivat Har Etzion ..........607 at Bar Ilan University ...........819 Midreshet Lindenbaum. .102 Nishmat ........................619 Machon Maayan ................306 Midreshet Moriah ...............401 Sha’alvim for Women ............418 Michlalah Jerusalem College ....501 Midreshet Tehillah ..............818 Tiferet ......................... 406 UNDERGRADUATE WOMEN Michlelet Mevaseret Midreshet Torah V’Avodah ......301 Tomer Devorah ................ 906 Yerushalayim ..................518 Midreshet Torat Chessed ........315 These schools do not participate in the S. Daniel Abraham Israel Program STERN COLLEGE FOR WOMEN Amudim ........................918 Bilvavi ......................... 606 Baer Miriam ...................1019 Meorot Yerushalayim ..........1015 SY SYMS SCHOOL OF BUSINESS THE KATZ SCHOOL OPEN HOUSE AND ISRAEL FAIR SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 11, 2018 PROGRAM SCHEDULE | Office of Admissions | 646.592.4440 | [email protected] WELCOME TO YESHIVA UNIVERSITY 11 a.m. – 2 p.m. CAMPUS TOURS LAB TOURS leave regularly from the Rae Kushner Lobby of 245 Lexington Avenue 9 – 9:30 a.m. REGISTRATION 245 Lexington Avenue, between 34th and 35th Streets DORM TOURS leave regularly from Brookdale Residence Hall, 50 East 34th Street, between Park and Madison Avenues 9:30 – 10:30 a.m.