Implementing Equity Crowdfunding in the Record

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PREMIÈRES RÉFLEXIONS ET ÉTAT DES LIEUX DU CROWD- FUNDING Du Lien Entre Le financement Et Le Porteur De Projet

Vous avez dit crowdfunding ? Réflexions prospectives et repères pratiques PREMIÈRES RÉFLEXIONS ET ÉTAT DES LIEUX DU CROWD- FUNDING du lien entre le financement et le porteur de projet. Cela répond également à des besoins de financement qui ne sont pas pourvus INTRODUCTION par les dispositifs traditionnels. Tel est le cas de l’equity gap. Equity gap L’equity gap est traduit par « trou de financement » ou Entraide financière : « vallée de la mort ». Il se définit comme un déficit de capital un phénomène ancien social (« equity ») à différents stades de la chaîne de financement. Cette chaîne suppose une continuité entre les différents acteurs La solidarité financière ne date pas de notre époque contem- qui se succèdent au cours du développement de l’entreprise. poraine. Fondée sur des réseaux sociaux et une logique de communauté, elle se retrouve dans les sociétés archaïques et En France, cette chaîne s’interrompt, le plus souvent, après l’inter- prémodernes sous différentes formes. Tel est le cas du potlatch, vention des Business Angels (BA) et avant celle du capital-risque qui repose sur le principe du don au sein d’une communauté, ou qualifié également de Venture Capital (VC). Selon l’Institut de de la tontine qui repose sur le principe d’une caisse commune Recherche pour la Démographie des Entreprises, ce manque de à laquelle abondent plusieurs personnes à parts égales, et qui financement est estimé à 4 milliards € et concerne essentiellement reviendra au dernier survivant du groupe. Il s’agit donc d’une la tranche entre 500 K€ et 2 millions € 2. logique sociale basée sur la solidarité entre les membres du groupe, la confiance et les liens qui les unissent. -

Powering the Crowd Into the Future

POWERING THE CROWD INTO THE FUTURE KEY LEARNINGS & RECOMMENDATIONS Davinia Cogan, Peter Weston POWERING THE CROWD INTO THE FUTURE KEY LEARNINGS & RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ENERGY ACCESS CROWDFUNDING AND P2P LENDING CONTENTS BIOS 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 INTRODUCTION 6 1 STATE OF THE MARKET 8 2 THE 6 CAMPAIGN ARCHETYPES 12 1. PARTNERSHIP MODELS 15 CASE STUDY: TAHUDE FOUNDATION 16 2. ONE-OFF FUNDRAISERS 17 CASE STUDY: RAFODE 19 CASE STUDY: SOLARIS OFFGRID 20 3. MEGA-CAMPAIGNS 22 4. P2P MICROLENDING 23 CASE STUDY: EMERGING COOKING SOLUTIONS 24 5. ONLINE DEBT-BASED SECURITIES 26 CASE STUDY: SIMUSOLAR 27 CASE STUDY: AZURI TECHNOLOGIES 29 5.EQUITY CROWDFUNDING 31 CASE STUDY: TRINE 32 3 INTERVENTIONS TO CATALYSE FUNDING 34 4 CROWD POWER UPDATE 37 CONCLUSION 39 REFERENCES 41 This material has been funded by UK aid from the UK government; however the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. Published December 2018 Design: www.dougdawson.co.uk Front cover by C.Schubert BIOS Davinia Cogan Peter Weston Davinia Cogan is the Programme Peter Weston is the Director of Manager of Crowd Power at Energy Advisory Services at Energy 4 Impact. 4 Impact. She runs the UK aid He manages a team of consultants funded programme, which explores that advises off-grid SMEs in Sub the role of incentives to stimulate Saharan Africa and helps them to donation, reward, debt and equity implement new business models crowdfunding in the off-grid energy and technologies. He is an expert sector in Sub- Saharan Africa and in power, renewables and off- South Asia. -

Jun Zhang (10742239) Msc

To Which Extend Do Material Incentives Matter? A Study on Backers’ Motivation behind Crowdfunding Behaviour Master Thesis Student: Jun Zhang (10742239) MSc. in Business Administration - Entrepreneurship and Innovation Faculty of Business and Economics of UvA Supervisor: First Supervisor: Dr. G.T. Vinig Second Supervisor: Dr. W. van der Aa Date: 26 Jun 2015 (Final Version) Statement of Originality This document is written by Student Jun Zhang, who declares to take full responsibility for the contents of this document. I declare that the text and the work presented in this document is original and that no sources other than those mentioned in the text and its references have been used in creating it. The Faculty of Economics and Business is responsible solely for the supervision of completion of the work, not for the contents. Page 2 of 91 Contents Acknowledgement ..................................................................................................................... 5 Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 6 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Academic Relevance ................................................................................................. 10 1.2 Managerial Relevance ............................................................................................... 11 1.3 Thesis Outline .......................................................................................................... -

Girişimciler Için Yeni Nesil Bir Finansman Modeli “Kitle Fonlamasi - Crowdfunding”: Dünya Ve Türkiye Uygulamalari Üzerine Bir Inceleme Ve Model Önerisi

T.C. BAŞKENT ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ İŞLETME ANABİLİM DALI İŞLETME DOKTORA PROGRAMI GİRİŞİMCİLER İÇİN YENİ NESİL BİR FİNANSMAN MODELİ “KİTLE FONLAMASI - CROWDFUNDING”: DÜNYA VE TÜRKİYE UYGULAMALARI ÜZERİNE BİR İNCELEME VE MODEL ÖNERİSİ DOKTORA TEZİ HAZIRLAYAN ASLI VURAL TEZ DANIŞMANI DOÇ. DR. DENİZ UMUT DOĞAN ANKARA- 2019 TEŞEKKÜR Beni her konuda daima destekleyen, cesaretlendiren, güçlü olmayı öğreten, mücadeleden, öğrenmekten ve kendimi geliĢtirmekten vazgeçmemeyi ilke edindiren, sevgili babama ve rahmetli anneme, Sevgisini ve desteğini daima hissettiğim değerli eĢime, Tezimin her aĢamasında bana tecrübesi ve bilgi birikimiyle yol gösteren, ilgi ve desteğini esirgemeyen tez danıĢmanım Doç. Dr. Deniz Umut DOĞAN’a, Çok değerli görüĢleri ve yönlendirmeleri için Prof. Dr. Nalan AKDOĞAN’a, ÇalıĢma dönemimde destek ve yardımını benden hiç esirgemeyen Çiğdem GÖKÇE’ye ve sevgili dostlarıma, En içten duygularımla teĢekkür ederim. I ÖZET GiriĢimcilerin en önemli problemi finansal kaynaklara ulaĢmalarında yaĢadıkları zorluklardır. GiriĢimciler finansal sorunlarını çözmek için geleneksel finansman yöntemlerinden ve Risk Sermayesi, GiriĢim Sermayesi, Bireysel Katılım Sermayesi, Mikrofinansman gibi alternatif finansman modellerinden yararlanmaktadır. Günümüzde giriĢimcilerin gereksinim duydukları sermayeye ulaĢmak için kullandıkları yeni finansal yöntemlerden biri Kitle Fonlaması modelidir. ÇalıĢmada giriĢimcilik, giriĢim finansmanı ve Kitle Fonlaması modeli konusunda literatür taraması yapılarak ilgili kavramlara değinilmiĢtir. Dünya’da -

Current State of Crowdfunding in Europe

Current State of Crowdfunding in Europe An Overview of the Crowdfunding Industry in more than 25 Countries: Trends, Volumes & Regulations 2016 Current State of Crowdfunding in Europe 2016 CrowdfundingHub is the European Expertise Centre for Alternative and Community Finance [email protected] www.crowdfundinghub.eu @CrowdfundingHub.eu Keizersgracht 264 1016 EV Amsterdam The Netherlands This report is made possible by the contribution of: Current State of Crowdfunding in Europe is a report based on research conducted by CrowdfundingHub in close cooperation with professionals from all over Europe. Revised versions of this report and updates of individual countries can be found at www.crowdfundingineurope.eu. Current State of Crowdfunding in Europe 2016 Foreword We started this research to get a structured view on the state of crowdfunding in Europe. With the support of more than 30 experts in Europe we collected information about the industry in 27 countries. One of the conclusions is that there is a wide variety of alternative finance instruments that is being offered through online platforms and also that the maturity of the alternative finance industry in a country can not just be measured by the volume of transactions on these platforms. During the process of the research therefore, the idea took root to develop an Alternative Finance Maturity Index. The index takes into account the volumes in the industry, the access to relevant and reliable data, the degree of organization of the industry, the presence and use of all the different forms of alternative finance and also the way governments are regulating the industry with rules that on one hand foster alternative finance but on the other hand also protect consumers and prevent excesses. -

CROWD FUNDING – a NEW WAVE for the SUCCESSFUL INDIAN ENTREPRENUER’S

International Journal of Engineering & Scientific Research Vol. 6 Issue1, January 2018, ISSN: 2347-6532 Impact Factor: 6.660 Journal Homepage: http://esrjournal.com, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell‟s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A CROWD FUNDING – A NEW WAVE FOR THE SUCCESSFUL INDIAN ENTREPRENUER’s Dr. J. Venkatesh* & Dr. R. Lavanya Kumari** Dr. J. VENKATESH* Associate Professor Department of Management Studies Anna University Regional Campus Coimbatore, Navavoor, Coimbatore – 641 046. Tamil Nadu, INDIA Dr. R. LAVANYA KUMARI** Associate Professor, Department of Business Management David Memorial Institute of Management Tarnaka, Hyderabad – 500017, Telangana, INDIA ABSTRACT The crowdfunding is an application on crowd sourcing. This concept implemented in the year 2000 and has been developing hastily all around the world. Over the last years crowdfunding emerged as an alternative investment channel for entrepreneurs. In assessment to traditional financiers (banks, venture capital firms or angel investors), crowdfunding lets in people to fund entrepreneurs directly in spite of small amounts. Crowdfunding is the exercise of funding a project by using raising money from a big range of people. It presents new investment avenues and offers a brand new product for portfolio diversification of investors. Crowdfunding is a new paradigm for the younger people to start up an enterprise. The objective of this paper has been focus on benefits & types; it‟s a brand new wave for the successful Indian Entrepreneurs. -

Are You Ready to Raise Money for Your Business? What Funders Will Fund Small Business Support & Tools Resource List

GOOD MONEY GUIDE GOOD MONEY GUIDE GOOD MONEY GUIDE INSIDE: Are you ready to raise money for your business? What Funders will Fund Small Business Support & Tools Resource List and more... WE’RE HERE TO HELP YOUR BUSINESS PROSPER Whether you’re starting a new business, We’re working to grow the local economy expanding your operations, or relocating in an equitable manner, so that Oakland to Oakland, our business conceirge team is remains a unique, special place to live, do here to help your buisness prosper. business and prosper together. From navigating business permitting and To request help, take the online self licensing to connecting you with Oakland’s assessment at oaklandbusinesscenter.com. rich ecosystem of business support (510) 238-7398 organizations to assisting with workforce [email protected] recruitment, our team members can provide referrals and resources to help you Economic & Workforce CITY OF start or grow your business in Oakland. Development Department Oakland Good MONEY 2021 GOOD MONEY GUIDE 2 DEDICATION The Zulu philosophy of Ubuntu is rooted in the notion that “I am because we are.” In essence, it means that as a human being, you—your humanity, your personhood—are fostered in relation to other people. We at Alliance for Community Development take this philosophy to heart. All that we are, including who and what we center our work in, how we achieve our mission and what organizations we partner with to do so, is a reflection of each and every person who makes up our community. This year, we dedicate the 2020 Good Money Guide, our labor of love rooted in equity and shared knowledge, to our community: the entrepreneurs, community members, advisors, and funders that make up our ecosystem and have included us into their lives, their businesses, and their hopes and dreams over the past 20 years. -

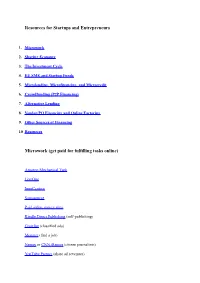

Resources for Startups and Entrepreneurs Microwork

Resources for Startups and Entrepreneurs 1. Microwork 2. Sharing Economy 3. The Investment Cycle 4. EU SME and Startup Funds 5. Microlending, Microfinancing, and Microcredit 6. Crowdfunding (P2P Financing) 7. Alternative Lending 8. Vendor/PO Financing and Online Factoring 9. Other Sources of Financing 10 Resources Microwork (get paid for fulfilling tasks online) Amazon Mechanical Turk LiveOps InnoCentive Samasource Paid online survey sites Kindle Direct Publishing (self-publishing) Craiglist (classified ads) Monster (find a job) Newsy or CNN iReport (citizen journalism) YouTube Partner (share ad revenues) CCNow (accept credit cards and PayPal payments) Amazon Associates (get a commission on referred sales) EBay or Etsy or Alibaba (sell things, including handicrafts) Shareconomy (Sharing Economy) View introductory video AirBnB or Couchsurfing (share your home for a fee) Eatwith or Kitchensurfing (host a meal and get paid) Vayable (become a tour guide) Uber or Lyft or Sidecar (give rides in your car) BorrowedBling or Girl Meets Dress or Rent the Runway (lend your jewelry and haute couture for a fee) Yerdle or Snap Goods (Simplist) or Open Shed (swap, rent, or borrow things) Relay Rides or Getaround (rent out your car) Favor Delivery (get deliveries – or deliver) Task Rabbit (handyman services) Waze (community rides) The Investment Cycle Register firm in target market Doing Business Equity structure Common stock Stock options Convertible debt Series A Preferred Stock (convertible to common stock on IPO/sale) Investment Cycle - Overview Seed -

Journal of Management and Business Administration Central Europe Vol

„Journal of Management and Business Administration. Central Europe” Vol. 26, No. 1/2018, p. 49–78, ISSN 2450-7814; e-ISSN 2450-8829 © 2018 Authors. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/) How do we study crowdfunding? An overview of methods and introduction to new research agenda1 Agata Stasik2, Ewa Wilczyńska3 Submitted: 19.07.2017. Final acceptance: 12.12.2017 Abstract Purpose: Crowdfunding is a global phenomenon of rising significance and impact on different areas of business and social life, investigated across many academic disciplines. The goal of the article is to present the variety of methods applied in crowdfunding research, assess their strengths and weaknesses, offer the typology of methodological approaches, and suggest the most promising direction for further studies. Design/methodology: The paper is based on the review of the most recent academic and industry lite rature on crowdfunding and own analysis of data presented by crowdfunding platforms’ operators. Findings: The article incorporates interrelations of methods, goals of inquiries, and types of results to propose a typology of methodological approaches that researchers currently apply to crowdfund ing: from platformcentred to multisited. The authors discuss the advantages and limitations of the identified approaches with the use of multiple examples of recent and most influential studies from the field and propose the most urgent direction of future inquiries. Research limitations/implications: The overview renders crowdfunding studies more accessible for potential newcomers to the field and strengthens transdisciplinary discussion on crowdfunding. Despite the broad variety of the analyzed articles that reflect the newest trends, the sample is not representative in the statistical meanings of the term. -

The Crowdfunding Book

Praise for The Crowdfunding Book: If you have a business dream and need a little (or a lot) of cash to get it going, Patty Lennon's insights will be invaluable. - Shawn Hull, Successful Crowdfunder and Owner, Hull’s Happiest Days Designs Until I read Patty Lennon's book, I always thought of crowdfunding as a way to raise money. Once I understood her approach I saw the tremendous marketing potential of crowdfunding. I can't think of a better or more cost-effective way to build a community of people who support you and your message. - Angela Lauria, President, The Author Incubator Patricia Lennon is the source for the crowdfunding industry. This book will help explore the topic and give a better understanding to all who are interested in learning more. - Amanda L. Barbara, Vice President, Pubslush Patty Lennon takes the mystery out of crowdfunding in The Crowdfunding Book. Her practical and engaging approach will help thousands of people launch successful campaigns and raise the funds to realize their dreams. - Brenda Bazan and Nancy Hayes, CoFounders, MoolaHoop THE CROWDFUNDING BOOK: A How-to Book for Entrepreneurs, Writers, and Inventors Patty Lennon The Crowdfunding Book: A How-to Book for Entrepreneurs, Writers, and Inventors Patty Lennon © 2014 Patty Lennon All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher and author. Reviewers may quote brief passages in reviews. Published by Difference Press, Washington DC Difference Press, and the Difference Press wax seal design are registered trademarks of Becoming Journey LLC. -

Crowd Power – Success & Failure, the Key to a Winning Campaign

CROWD POWER Success & Failure: The Key to a Winning Campaign Davinia Cogan and Simon Collings 1 CONTENTS 1.0 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................3 2.0 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................5 3.0 The Layers of Success ..............................................................................................................................7 3.1 Donation .........................................................................................................................................................11 3.1.1 Choosing the Right Platform....................................................................................................................................................................11 3.1.2 The Campaign Period ..................................................................................................................................................................................13 3.1.3 Implementing Campaign Goals & Success into the Future .......................................................................................16 3.1.4 Q&A – Kenya Green Supply ..............................................................................................................................................18 3.2 Reward .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Istanbul Technical University Graduate School of Arts

ISTANBUL TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES CROWDFUNDING COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT: DRIVERS AND OUTCOMES Ph.D. THESIS Melek DEMİRAY Department of Management Management Programme AUGUST 2019 ISTANBUL TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES CROWDFUNDING COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT: DRIVERS AND OUTCOMES Ph.D. THESIS Melek DEMİRAY (403132003) Department of Management Management Programme Thesis Advisor: Prof. Dr. Şebnem BURNAZ AUGUST 2019 İSTANBUL TEKNİK ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ KİTLE FONLAMASINDA TOPLULUK KATILIMI: ÖNCÜLLER VE ÇIKTILAR DOKTORA TEZİ Melek DEMİRAY (403132003) İşletme Anabilim Dalı İşletme Doktora Programı Tez Danışmanı: Prof. Dr. Şebnem BURNAZ AĞUSTOS 2019 Melek Demiray, a Ph.D. student of ITU Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences student ID 403132003, successfully defended the thesis entitled “CROWDFUNDING COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT: DRIVERS AND OUTCOMES”, which she prepared after fulfilling the requirements specified in the associated legislations, before the jury whose signatures are below. Thesis Advisor : Prof. Dr. Şebnem BURNAZ .............................. Istanbul Technical University Jury Members : Doç. Dr. Mehmet ERÇEK ............................. Istanbul Technical University Prof. Dr. Yonca ASLANBAY .............................. Istanbul Bilgi University Prof. Dr. A. Banu ELMADAĞ BAŞ .............................. Istanbul Technical University Prof. Dr. Nimet URAY .............................. Kadir Has University Date of Submission : 09 July 2019 Date of Defense : 07 August 2019 v vi To my family, vii viii FOREWORD This Ph.D. thesis would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of many individuals. I would like to take this opportunity to acknowledge them. I would like to first thank to my supervisor Prof. Şebnem BURNAZ for her guidance, support, invaluable suggestions at all stages of this study. Without her encouragement, this Ph.D.