Notes of the Feeding Behavior of the Common Merganser (Mergus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diving Ducks Wildlife Note

Diving Ducks Pennsylvania ducks may be grouped into two types: diving ducks and dabbling or puddle ducks. Diving ducks often spend much more of their time farther out from shore than puddle ducks. Both groups can be found on streams, rivers, lakes and marshes. This note covers 15 species commonly called diving ducks. redhead Diving ducks eat seeds and other parts of aquatic plants, form monogamous pairs that last until the female begins fish, insects, mollusks, crustaceans and other invertebrates. incubating eggs; then, the male leaves the area and usually They dive underwater to obtain much of their food. They joins a band of other males. have large broad feet, fully webbed and with strongly lobed hind toes, that act as paddles. Their legs are spaced Nesting habits and habitats vary from species to species. widely apart and located well back on the body, improving Generally, female diving ducks lay 5 to 15 eggs in diving efficiency but limiting agility on land. Their bodies vegetation, tree cavities, or rock crevices over or near the are compact, and their wings have relatively small surface water. Because females do not start incubating a clutch areas; noticeably more narrow than puddle ducks. While until they lay their last egg, young develop simultaneously this arrangement helps their diving and swimming, it and all hatch at about the same time. hinders their ability to become airborne. Instead of Ducklings are covered with down, patterned with shades springing straight out of the water into flight, as puddle of yellow or brown to break up their body outlines. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

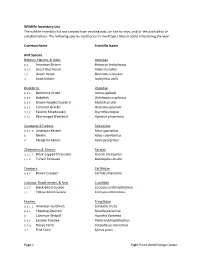

Master Wildlife Inventory List

Wildlife Inventory List The wildlife inventory list was created from existing data, on site surveys, and/or the availability of suitable habitat. The following species could occur in the Project Area at some time during the year: Common Name Scientific Name Bird Species Bitterns, Herons, & Allies Ardeidae D, E American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus A, E, F Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias E, F Green Heron Butorides virescens D Least bittern Ixobrychus exilis Blackbirds Icteridae B, E, F Baltimore Oriole Icterus galbula B, E, F Bobolink Dolichonyx oryzivorus B, E, F Brown-headed Cowbird Molothrus ater B, E, F Common Grackle Quiscalus quiscula B, E, F Eastern Meadowlark Sturnella magna B, E, F Red-winged Blackbird Agelaius phoeniceus Caracaras & Falcons Falconidae B, E, F, G American Kestrel Falco sparverius B Merlin Falco columbarius D Peregrine Falcon Falco peregrinus Chickadees & Titmice Paridae B, E, F, G Black-capped Chickadee Poecile atricapillus E, F, G Tufted Titmouse Baeolophus bicolor Creepers Certhiidae B, E, F Brown Creeper Certhia americana Cuckoos, Roadrunners, & Anis Cuculidae D, E, F Black-billed Cuckoo Coccyzus erythropthalmus E, F Yellow-billed Cuckoo Coccyzus americanus Finches Fringillidae B, E, F, G American Goldfinch Carduelis tristis B, E, F Chipping Sparrow Spizella passerina G Common Redpoll Acanthis flammea B, E, F Eastern Towhee Pipilo erythrophthalmus E, F, G House Finch Carpodacus mexicanus B, E Pine Siskin Spinus pinus Page 1 Eight Point Wind Energy Center E, F, G Purple Finch Carpodacus purpureus B, E Red Crossbill -

Life History Account for Common Merganser

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group COMMON MERGANSER Mergus merganser Family: ANATIDAE Order: ANSERIFORMES Class: AVES B105 Written by: T. Harvey Reviewed by: S. Bailey Edited by: C. Polite DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALITY Uncommon to locally common breeder on lakes, ponds, and large streams of the Coast, Klamath, Cascade, and Sierra Nevada Ranges. Winters in small flocks on large, fresh waters in the Coast, Klamath, and Cascade Ranges, and foothills of the Sierra Nevada. Also occurs in the Central Valley, Modoc Plateau, Transverse, and Peninsular Ranges in nonbreeding seasons. Found commonly on the Colorado River November through April, and uncommonly on the Salton Sea. SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: Forages in clear water 0.5 to 1.8 m (1.5 to 6.1 ft) deep. Swims on the surface, searches underwater, and dives for fish. Also probes among submerged rocks to flush out prey (Anderson et al. 1974). In Canada, fed on perch, carp, trout, salmon, fish eggs, aquatic invertebrates, frogs, newts, tadpoles, and small amounts of aquatic plants (White 1957). Duckling feeds on insects caught beneath the water. Cover: Dives for cover. Reproduction: Breeds in deciduous riparian habitats in later forest stages, along streams, rivers, and lakes. Nests in cavities or dark recesses in trees, snags, and stumps near water; especially old cavities of pileated woodpecker. Also may nest in caves in cliffs, in tangles of roots, beneath rocks, and in nest boxes; occasionally in holes in buildings. Nest height 0-61 m (0-200 ft). Nest lined, and eggs covered, with grass and down. -

1 CWU Comparative Osteology Collection, List of Specimens

CWU Comparative Osteology Collection, List of Specimens List updated November 2019 0-CWU-Collection-List.docx Specimens collected primarily from North American mid-continent and coastal Alaska for zooarchaeological research and teaching purposes. Curated at the Zooarchaeology Laboratory, Department of Anthropology, Central Washington University, under the direction of Dr. Pat Lubinski, [email protected]. Facility is located in Dean Hall Room 222 at CWU’s campus in Ellensburg, Washington. Numbers on right margin provide a count of complete or near-complete specimens in the collection. Specimens on loan from other institutions are not listed. There may also be a listing of mount (commercially mounted articulated skeletons), part (partial skeletons), skull (skulls), or * (in freezer but not yet processed). Vertebrate specimens in taxonomic order, then invertebrates. Taxonomy follows the Integrated Taxonomic Information System online (www.itis.gov) as of June 2016 unless otherwise noted. VERTEBRATES: Phylum Chordata, Class Petromyzontida (lampreys) Order Petromyzontiformes Family Petromyzontidae: Pacific lamprey ............................................................. Entosphenus tridentatus.................................... 1 Phylum Chordata, Class Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fishes) unidentified shark teeth ........................................................ ........................................................................... 3 Order Squaliformes Family Squalidae Spiny dogfish ........................................................ -

Species List-Includes Birds (Pdf)

Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge Birds List Common Name Scientific Name Federal State Occurrence Classification Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons native Snow Goose Chen hyperborea native Ross’s Goose Chen rossii native Canada Goose Branta canadensis nests locally native Cackling Goose Branta hutchinsii native Brant Branta bernicla SSC native Tundra Swan Cygnus columbianus native Gadwall Anas strepera nests locally native Eurasian Wigeon Anas penelope native American Wigeon Anas americana native Mallard Anas platyrhynchos nests locally native Blue-winged Teal Anas discors native Cinnamon Teal Anas cyanoptera nests locally native Northern Shoveler Anas clypeata nests locally native Northern Pintail Anas acuta nests locally native Green-winged Teal Anas crecca native Canvasback Aythya valisineria nests locally native Redhead Aythya americana SSC native Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris native Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula non-native Greater Scaup Aythya marila native Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis nests locally native Surf Scoter Melanitta perspicillata native White-winged Scoter Melanitta fusca native Black Scoter Melanitta nigra native Long-tailed Duck Clangula hyemalis native Bufflehead Bucephala albeola native Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula native Barrow’s Goldeneye Bucephala islandica native Hooded Merganser Lophodytes cucullata native Common Merganser Mergus merganser native Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator native Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis nests locally native California Quail Callipepla californica -

Japan in Winter

JAPAN IN WINTER JANUARY 19–31, 2019 Red-crowned Crane roost, Setsuri River, Tsurui, Hokkaido - Photo: Arne van Lamoen LEADERS: KAZ SHINODA & ARNE VAN LAMOEN LIST COMPILED BY: ARNE VAN LAMOEN VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM JAPAN IN WINTER: A CRANE & SEA-EAGLE SPECTACLE! By Arne van Lamoen For a trip as unique as VENT’s “Japan in Winter” tour, it is very difficult to reduce an eleven-day trip into a single, representative highlight. Moreover, to do so would be to eschew a great many other lifetime memories unlikely to be objectively less remarkable. I content myself here to a smattering then, in the interest of brevity, but as is so often the case when describing the beauty and majesty of nature—and birds in particular—mere words will not do these sightings justice. This tour featured several new life birds for even our most seasoned and almost impossibly well-traveled participants, Trent and Meta. I know that for them, the Japanese endemics (and near endemics) such as the Ryukyu Minivet sighted in Kyushu ( Pericrocotus tegimae ) and resident Red-crowned Cranes in Hokkaido ( Grus japonensis ) were among several trip highlights. For others, the inescapable grandeur and majesty of Steller’s Sea-Eagles ( Haliaeetus pelagicus ), both perched on snowy trees and overhead in flight, could not be denied. I count myself among them. Still others were enamored with the rare Baikal Teals ( Sibirionetta formosa ) spotted in a partially iced-over reservoir on Kyushu and the even (globally) rarer Black-faced Spoonbills ( Platalea minor ) and solitary Saunder’s Gull ( Chroicocephalus saundersi ) which we sighted not five minutes apart along the Hi River. -

MD-Birds-2021-Envirothon-3Pp

3/23/2021 Maryland Envirothon: Class Aves KERRY WIXTED WILDLIFE AND HERITAGE SERVICE March 2021 1 Aves Overview •> 450 species in Maryland •Extirpated species include: ◦Bewick’s Wren ◦Greater Prairie Chicken ◦Red-cockaded Woodpecker American Woodcock (Scolopax minor) chick by Kerry Wixted Note: This guide is an overview of select species found in Maryland. The taxonomy and descriptions are based off Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Eastern and Central North America, 6th Ed. 2 Order: Anseriformes • Web-footed waterfowl • Family Anatidae • Ducks, geese & swans Male Wood Duck (Aix sponsa) Order: Anseriformes; Family Anatidae 3 1 3/23/2021 Cygnus- Swans Mute Swan Tundra Swan Trumpeter Swan (Cygnus olor) (Cygnus columbianus) (Cygnus buccinator) Invasive. Adult black-knobbed orange Winter resident. Adult bill black, usually Winter resident. Adult all black bill bill tilts down; immature is dingy with with small yellow basal spot; immature with straight ridge; more nasal calls is dingy in color with pinkish bill; makes than tundra swan pinkish bill; makes hissing sounds mellow-high pitched woo-ho, woo-woo noise Order: Anseriformes; Family Anatidae By Matthew Beziat CC by NC 2.0 By Jen Goellnitz CC by NC 2.0 4 Dabbling Ducks- feed by dabbling & upending Male Female , Maryland Biodiversity Project Biodiversity ,Maryland Hubick By Bill Bill By By Kerry Wixted Kerry By American Black Duck (Anas rubripes) Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) Year-round resident. Dusky black duck with white wing linings Year-round resident. Adult males have green head w/ evident in flight; resembles a female mallard but has black white neck ring & females are mottled in color ; borders on secondary wing feathers; can hybridize with resembles an American Black Duck mallard but has mallards white borders on secondary wing feathers Order: Anseriformes; Family Anatidae 5 Diving Ducks- feed by diving; legs close to tail CC by NC NC 2.0CC by Beziat By Judy Gallagher CC by by 2.0CC Gallagher Judy By By Matthew Matthew By Canvasback (Aythya valisneria) Redhead (Aythya americana) Winter resident. -

Learn About Texas Birds Activity Book

Learn about . A Learning and Activity Book Color your own guide to the birds that wing their way across the plains, hills, forests, deserts and mountains of Texas. Text Mark W. Lockwood Conservation Biologist, Natural Resource Program Editorial Direction Georg Zappler Art Director Elena T. Ivy Educational Consultants Juliann Pool Beverly Morrell © 1997 Texas Parks and Wildlife 4200 Smith School Road Austin, Texas 78744 PWD BK P4000-038 10/97 All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems – without written permission of the publisher. Another "Learn about Texas" publication from TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE PRESS ISBN- 1-885696-17-5 Key to the Cover 4 8 1 2 5 9 3 6 7 14 16 10 13 20 19 15 11 12 17 18 19 21 24 23 20 22 26 28 31 25 29 27 30 ©TPWPress 1997 1 Great Kiskadee 16 Blue Jay 2 Carolina Wren 17 Pyrrhuloxia 3 Carolina Chickadee 18 Pyrrhuloxia 4 Altamira Oriole 19 Northern Cardinal 5 Black-capped Vireo 20 Ovenbird 6 Black-capped Vireo 21 Brown Thrasher 7Tufted Titmouse 22 Belted Kingfisher 8 Painted Bunting 23 Belted Kingfisher 9 Indigo Bunting 24 Scissor-tailed Flycatcher 10 Green Jay 25 Wood Thrush 11 Green Kingfisher 26 Ruddy Turnstone 12 Green Kingfisher 27 Long-billed Thrasher 13 Vermillion Flycatcher 28 Killdeer 14 Vermillion Flycatcher 29 Olive Sparrow 15 Blue Jay 30 Olive Sparrow 31 Great Horned Owl =female =male Texas Birds More kinds of birds have been found in Texas than any other state in the United States: just over 600 species. -

Use of Geolocators Reveals Previously Unknown Chinese and Korean Scaly-Sided Merganser Wintering Sites

Vol. 17: 217–225, 2012 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Published online June 15 doi: 10.3354/esr00429 Endang Species Res Use of geolocators reveals previously unknown Chinese and Korean scaly-sided merganser wintering sites Diana V. Solovyeva1, Vsevolod Afanasiev2, James W. Fox2,3, Valery Shokhrin4, Anthony D. Fox5,* 1Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Building 1, Universitetskaya Embankment, Saint Petersburg 199034, Russia 2British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0ET, UK 3Migrate Technology Ltd, PO Box 749, Coton, Cambridge CB1 0QY, UK 4Lazovskiy State Reserve, 56 Tsentralnaya Street, Lazo, Primorskiy Kray, 692980, Russia 5Institute of Bioscience, Aarhus University, Grenåvej 14, 8410 Rønde, Denmark ABSTRACT: We determined, for the first time, individual linkages between breeding areas of nesting female scaly-sided mergansers Mergus squamatus in the Russian Far East and their pre- viously unknown wintering grounds in coastal Korea and inland China. Geolocators were deployed on nesting females caught and recaptured on nests along a 40-km stretch of the Kievka River. Mean positions for brood-rearing females during the summer were on average within 61.9 km of the nest site, suggesting reasonable device accuracy for subsequent location of winter quarters. Geolocation data showed that most birds wintered on freshwater habitats throughout mainland China, straddling an area 830 km E−W and 1100 km N−S. Most wintered in discrete mountainous areas with extensive timber cover, large rivers and low human population density. Three birds tracked in more than one season returned to within 25−150 km of previous wintering areas in successive years, suggesting winter fidelity to catchments if not specific sites. -

Cms Convention on Migratory Species

CMS CONVENTION ON Distribution: General MIGRATORY UNEP/CMS/ScC17/Inf.17 3 November 2011 SPECIES Original: English 17 TH MEETING OF THE CMS SCIENTIFIC COUNCIL Bergen, 17-18 November 2011 Agenda Item 17.3 CURRENT AND PREDICTED CONSERVATION STATUS OF CMS-LISTED ARCTIC MARINE SPECIES (in follow-up to Resolution 9.09) (Prepared by the Secretariat) 1. Resolution 9.09 on Migratory Marine Species adopted at the 9 th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties (Rome, 2008) calls for various actions relevant to Arctic marine species from both the CMS Secretariat and the Scientific Council. The Resolution was passed in response to concerns by Parties that marine species such as cetaceans, marine turtles, seabirds and migratory fish face a variety of threats that put cumulative and often synergistic pressure on populations. Of particular concern in this respect are the environmental changes to the Arctic region due to climate change, which can have grave consequences for migratory marine species occurring there and beyond. 2. In order to aid the Council in its task of reviewing the latest available information on the current and predicted conservation status, in relation to the possible consequences of climate change, of all Arctic migratory marine species listed on the CMS Appendices, the Secretariat had compiled a list of these species for the 16 th Meeting of the Council (Annex 1 of ScC16/Doc.11). For this exercise, Arctic marine species were defined as those that spend at least part of their lifecycle within the Arctic Circle. The final list contains fourteen species of cetaceans, twenty- seven bird and three fish species (Annex 1 to this document). -

Common Merganser (Mergus Merganser) Skye Christopher G

Common Merganser (Mergus merganser) Skye Christopher G. Haas Rogers City, MI © Willie McHale One of the more familiar sights to canoeists in (Click to view comparison of Atlas I & II) the North Woods is that of Common Distribution Mergansers. Whether it is a female guiding her Common Mergansers have been abundant in brood across a shallow bay, or the same pair of Michigan most likely since pre-settlement times. birds one keeps flushing all day, grunting as Barrows (1912) reported the species as a they fly up around the next bend in the river, common migrant breeding from Saginaw Bay they can be found on many of northern northward throughout the Upper Peninsula. Michigan’s waterways. Largest of Michigan’s MBBA I reported Common Mergansers as breeding waterfowl, this species is primarily a evenly distributed in the UP, but rather localized fish-eater, hunting its prey by sight or tactile in the LP, with concentrations in the Leelanau probing with its long, thin, serrated bill. Peninsula, the Beaver Islands, and north along Holarctic in distribution, it is known as the coast of Lake Michigan to the Mackinac Goosander in Eurasia. In North America, there Straits. There were also a few scattered interior are a variety of nick-names for this bird reports. One breeding record was confirmed in including sawbill, fish duck and sheldrake. A the SLP, at the tip of “the thumb,” in Huron river south of Whitefish Point in Chippewa County. County is named the Sheldrake. In this waterway, the Common Merganser is a regular At a time when so many bird species are in breeder and the likely inspiration for its name.