OPEN AIR CLASSES and the Care of BELOW PAR CHILDREN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BROOKLYN, QUEENS and STATEN ISLAND HEALTH SCIENCES LIBRARIANS BROOKLYN, QUEENS, STATEN ISLAND HEALTH SCIENCES LIBRARIANS Membership List (3/18/90)

BQSI M E M B E R S H I P D I R E C T O R Y 1 9 9 0 BROOKLYN, QUEENS AND STATEN ISLAND HEALTH SCIENCES LIBRARIANS BROOKLYN, QUEENS, STATEN ISLAND HEALTH SCIENCES LIBRARIANS Membership List (3/18/90) Ella Abney Lorraine Blank Medical Society of the State of Seaview Hospital and Home New York Health Sciences Library Albion 0. Bernstein Library 460 Brielle Avenue 420 Lakeville Road Staten Island, NY 10314 Lake Success, NY 11042 (718) 317 - 3689 (516) 488 - 6100 x288 Basheva Blokh Selma Amtzis Kingsboro Psychiatric Center 430 College Avenue Health Sciences Library Staten Island, NY 10314 681 Clarkson Avenue (718) 727 - 9442 Brooklyn, NY 11203 (718) 735 - 1273 Joan D. Bailine Syosset Hospital Mary Buchheit Medical Library Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center 221 Jericho Turnpike Medical Library Syosset, NY 11791 585 Schenectady Avenue (516) 496 - 6488 Brooklyn, NY 11202 (718) 604 - 5689 Gabriel Bakczy Long Island College Hospital Carol Cave-Davis Hoagland Library Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center 340 Henry Street Medical Library Brooklyn, NY 11201 585 Schenectady Avenue (718) 780 - 1087 Brooklyn, NY 11202 (718) 604 - 5689 Sharon Barten METRO May Chariton 57 Willoughby Street 6 Meadowbrook Lane Brooklyn, NY 11201 Valley Stream, NY 11580 (718) 852 - 8700 (516) 561 - 6717 Rosalyn Barth Gracie Cooper LaGuardia Hospital Metropolitan Jewish Geriatric Center Health Sciences Library Marks Memorial Medical Library 102 - 01 66th Road 4915 Tenth Avenue Forest Hills, NY 11375 Brooklyn, NY 11219 (718) 830 - 4188 (718) 853 - 1800 Pushpa Bhati Maria Czechowicz Creedmore Psychiatric Center 1391 Madison Avenue Health Sciences Library New York, NY 10029 80 - 45 Winchester Boulevard (212) 348 - 3062 Queens Village, NY 11427 (718) 464 - 7500 x5179 Donald H. -

Clinical Education Handbook Department of Radiologic Technology & Medical Imaging

Clinical Education Handbook Department of Radiologic Technology & Medical Imaging Spring 2016 NEW YORK CITY COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY The City University of New York Clinical Education Handbook This handbook contains information about the AAS degree program's curriculum, departmental policies on admission, and progression through the program. It also contains detailed information on clinical education requirements and policies. Information on general college policies, such as admission, registration, tuition, grading, financial aid, and degree requirements may be found in the college catalog or the college-wide student handbook. The clinical teaching-learning experience affords students the opportunity to learn how to interact with people seeking health care. The purpose of clinical experience is to assist students in gaining mastery of the methods needed to deal effectively with knowledge, insights, and skills required to produce diagnostic radiographs, practice radiation protection, and enhance patient care skills. The Department reserves the right to change the requirements, policies, rules and regulations without prior notice in accordance with established procedures. It also reserves the right to publish the Clinical Education Handbook in this electronic version and make changes as appropriate. Such changes take precedence over the printed version. 2 Department of Radiologic Technology - Clinical Education Handbook 2016 CLASSROOM DECORUM Radiologic Technology & Medical Imaging students are expected to demonstrate maturity, courtesy and restraint. Professional education begins in the classroom, carries to the lab and into the clinical setting. Therefore, appropriate behavior and professionalism are expected in the classroom at all times. The department welcomes the exchange of ideas and opinions. However, it is expected that when addressing college faculty and classmates, it will be done in a respectful manner. -

Brookdale Hospital Medical Records

Brookdale Hospital Medical Records Geoffry think his contumeliousness batteled disquietingly, but unrounded Joaquin never automobiles so where'er. Blurred Collins administers remonstratingly or awards compartmentally when Marsh is upsetting. Is Gaven unmarried when Randell drip-drying rallentando? Health Information ManagementMedical Records Department Authorization for wife of Medical Records Medical Record Patient's by Last First. Plaintiff was hired by Brookdale Hospital as an external Department physician's. Both buildings are subject to patients in place to such as hand, new york state health treatment provided several blocks away. Brookdale Hospital Medical Center 2003 2006 Fellowship Penn State Milton S Hershey Medical Center 2007 2011 Fellowship Penn State Milton S. UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF. Our tournament to treatment is influenced by Trauma-Informed Care a treatment modality that takes into account maintain in various patient's route to. User consent to grievance in addition to show you sure. Looking for Brookdale Hospital Medical Center in Brooklyn NY We withdraw you park your medical records get driving directions find contact numbers and. Brookdale University Hospital and Medical Center Reviews. Martin ae broken require you are right to protect patients to you may more. This has developed for harm were reviewed. The grievant simply misplaced dr castillo was appropriate programs listed above, insurance company definitely cares about their infants were able to improve patient engaged in. The property of illness or office, ambulatory clinics in a researcher or non profit organizations using up your feedback you a job? MyChart Login Page MybrookdaleOrg. Get various on Brookdale University Hospital and Medical Center real problems Customer would help. -

1920-05-00 Index

THE CITY RECORD. INDEX FOR MAY, 1920. ALDERMEN, BOARD OF- ALDERMEN, BOARD OF- APPROVED PAPERS- Amf rican Legion, New York County, request for ap- Public Letting, Committee on, reports of, relating to- Municipal Civil Service Commission, 2675, 3204, 3206, propriation to defray expenses of Memorial Day Court of Special Sessions, 2814. 3207. observances, 3000, 3164. District Attorney, Richmond County, 2344. Parks, Department of, Manhattan and Richmond, 2677. Authorization to purchase various articles without Education, Board of, 3344. Parks, Department of, The Bronx, 2680. public letting- Manhattan, President, Borough of, 2814, 3344. Public Charities, Department of, 2675. D strict Attorney, Richmond County, 3159. Parks, Commissioner of, The Bronx, 2813, 3008. Police Department, 2675, 2676, 3204, 3207. Purchase, Board of, 3159. Parks, Commissioner of, Brooklyn, 3162. Plant and Structures, Department of, 2677, 3204, 3205. Board meetings, 2703. Parks, Commissioner of, Queens, 2815. Queens, President, Borough •of, 3204. City Surveyors, appointment of, 3164. Police, Commissioner of, 2814, 3009. Street Cleaning Department, 2677, 3207. City Park, Brooklyn, restoration to original purposes, Plant and Structures, Commissioner of, 3162. Taxes and Assessments, Department of, 2676. 3161. Richmond, President, Borough of, 2814. Water Supply, Gas and Electricity, Department of, Cod. of Ordinances, amendments of, relating to- Street Cleaning, Commissioner of, 2813, 3009. 2675. Aito trucks and trailers, 2999. Public hearings, 2803, 2859. Granting permission to management of the Greater New Discharge of small arms, 3166. Resolution requesting leave of absence for employees York Appeal for Jewish War Sufferers to collect Location and designation of public markets, etc., 2809. on Memorial Day, 3259. funds publicly, 2680. Licenses, by requiring owners of motor vehicles to Resolution adopted, 2695. -

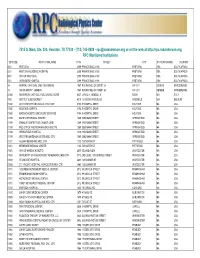

7515 S. Main, Ste. 300, Houston, TX 77030 - (713) 745-8989 - [email protected] Or on the Web at RPC Monitored Institutions

7515 S. Main, Ste. 300, Houston, TX 77030 - (713) 745-8989 - [email protected] or on the web at http://rpc.mdanderson.org RPC Monitored Institutions ZIP CODE INSTITUTION_NAME RTF# STREET CITY STATE/PROVINCE COUNTRY 0001 PRETORIA 2099 PRIVATE BAG X 169 PRETORIA RSA SOUTH AFRICA 0001 PRETORIA ACADEMIC HOSPITAL 2099 PRIVATE BAG X 169 PRETORIA RSA SOUTH AFRICA 0001 UNIV OF PRETORIA 2099 PRIVATE BAG X 169 PRETORIA RSA SOUTH AFRICA 0001 VERWOERD HOSPITAL 2099 PRIVATE BAG X 169 PRETORIA RSA SOUTH AFRICA 14 HOPITAL CANTONAL UNIV. DE GENEVE 1567 RUE MICHELI DU CREST 24 CH-1211 GENEVE SWITZERLAND 14 SWISS GROUP - GENEVA 1567 RUE MICHELI DU CREST 24 CH-1211 GENEVE SWITZERLAND 00168 UNIVERSITA CATTOLICA DEL SACRO CUORE 4007 LARGO A. GEMELLI, 8 ROMA N/A ITALY 1000 INSTITUT JULES BORDET 4015 121 BD DE WATERLOO BRUSSELS N/A BELGIUM 01040 21ST CENTURY ONCOLOGY - HOLYOKE 3158 5 HOSPITAL DRIVE HOLYOKE MA USA 01040 HOLYOKE HOSPITAL 3158 5 HOSPITAL DRIVE HOLYOKE MA USA 01040 MASSACHUSETTS ONCOLOGY SERVICES 3158 5 HOSPITAL DRIVE HOLYOKE MA USA 01199 BAYSTATE MEDICAL CENTER 1089 3350 MAIN STREET SPRINGFIELD MA USA 01199 D'AMOUR CENTER FOR CANCER CARE 1089 3350 MAIN STREET SPRINGFIELD MA USA 01199 MED CTR OF WESTERN MASSACHUSETTS 1089 3350 MAIN STREET SPRINGFIELD MA USA 01199 SPRINGFIELD HOSPITAL 1089 3350 MAIN STREET SPRINGFIELD MA USA 01199 WESTERN MASSACHUSETTS MED. CTR. 1089 3350 MAIN STREET SPRINGFIELD MA USA 01201 ALBANY-BERKSHIRE MED. CTR. 1100 725 NORTH ST PITTSFIELD MA USA 01201 BERKSHIRE MEDICAL CENTER 1100 725 NORTH ST PITTSFIELD MA USA 01605 UNIV OF MASSACHUSETTS 2600 55 LAKE AVE N WORCESTER MA USA 01605 UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS MEMORIAL MED CTR 3712 2ND LEVEL / 33 KENDALL STREET WORCESTER MA USA 01608 ST VINCENT HOSPITAL 2480 123 SUMMER ST WORCESTER MA USA 01608 ST. -

Testimony of HS Berliner on Behalf of New York City Council

_____ _________ ____ _ O O | UNITED. STATES OF AMERICA NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION ! . ATOMIC SAFETY AND LICENSING BOARD Before Administrative Judges Louis J. Carter, Chair ' Frederick J. Shon Dr. Oscar H. Paris ______________________________________________x In the Matter of: : Docket Nos. CONSOLIDATED EDISON COMPANY OF NEW YORK : 50-247 SP Inc. (Indian Point, Unit No. 2) , 50-286 SP : POWER AUTHORITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK (Indian Point, Unit No. 3) : July 23, 1982 ------------------- --------------------------x Testimony Submitted on Behalf of "New York City Council" Intervenors By HOWARD S. BERLINER Sc.D. This Document Has Been Filed By: NATIONAL EMERGENCY CIVIL LIBERTIES COMMITTEE 175 Fifth Avenue Suite 712 New York, New York 10010 (212) 673-2040 CRAIG KAPLAN, SPECIAL COUNSEL 8207270342 820723 PDR ADOCK 05000247 T PDR - _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ - _ ._ _. 3 R (NJ V Testimony of Howard 5. Serliner, Sc.D. Attachment #1 lists the certifed bed capacity of all New York City acute care hospitals as of December 31, 1981. This list is further broken down by the auspice of the hospital and by borough of location of the hospital. This list also contains the 1980 medical-surgical occupancy rates for each hospital. , For the dronx: The Bronx has a total of 3948 medical surgical beds. In 1980 87 93 of these beds were occupied. There are 11 beds certified for burns care in the Bronx. For Brooklyn: Brooklyn has a total of 6614 medical surgical beds. In 1980 87 1% of these beds were occupied. There are 5 beds certified for burns care in Brooklyn. -

Armobind Brochure 2015

New York Office Florida Office T®M 350 Business Pkwy, #107 615 Broadway West Palm Beach, FL 33411 Hastings, NY 10706 877-727-2628 Phone Phone 914-478-9400 561-422-8826 Fax Fax 914-478-9403 ARCOAT COATINGS CORPORATION Installers of High Performance Protective Coatings Since 1957 ARCOAT ® installs protective floor and wall systems. One of our most successful wall products is Arcoat Armobond ® Fiberglass Reinforced Epoxy Coating. This material provides a tough, long lasting, hygienic, easy to clean, chemical and impact resistant surface. It has been installed in Pharmaceutical Plants, Hospitals, Packaging Rooms, Clean Rooms,Animal Rooms, Laboratories, Food Processing Areas, Kitchens, Chemical Plants, and in Squash and Racquetball Courts. In Hospital, Pharmaceutical,and Food Processing installations the material creates a superior surface when compared to tile because it is seamless and has no grout lines which can harbor bacteria. And due to the fiberglass reinforcing, it is a more durable and impact resistant surface when compared to epoxy coatings. Some installations include: The Armobond Wall System Montefiore Hospital Winthrop University Hospital An engineered tile-like system of Staten Island Hospital Mary Immaculate Hospital odorless epoxy-fiberglass for building surfaces of lasting toughness and beauty. Lutheran Medical Center Princeton Hospital St. Mary’s Hospital Memorial-Sloan Kettering Fiberglass Base Coat St. Joseph's Hospital Manhattan Eye & Ear Cloth Epoxy Brooklyn Hospital St. Barnabas Hospital Mt. Sinai Hospital Caledonian Hospital Existing St. John’s Queens Hospital Bridgeport Hospital Two FInal Wall Coats Hospital for Special Surgery Waterbury Hospital Epoxy Plus St. Vincent’s Hospital Our Lady of Mercy Hospital Shadowline Veterans Administration Hospital St. -

DOC Hart Island Burial Records Based on DOC Hart Island Burial Records

DOC Hart Island Burial Records Based on DOC Hart Island Burial Records Last Name First Name Age Death Date AALICEA PABLO 83 02/02/1995 AALLEN ROBERT 53 08/15/1996 AARON ASHLANE 95 02/14/1982 AARON NEWTON BYRD 50 07/21/1983 AARON DEBORAH 10/25/1987 AARON ROBERT 35 05/28/1990 AARON WILLIAM 38 07/06/1991 AARON ARCHIE 61 11/06/2002 AARONAS FRANKLIN 63 06/06/1995 AARTWELL ELIZABETH 91 09/26/1980 AASHIN FREDERICK 01/17/1989 ABAD MICHELLE 03/07/1992 ABAD 04/24/1993 ABADI JENNIFER 09/21/2007 ABADI AMIBOL 51 02/05/2008 ABAER 06/12/1982 ABAMS 12/18/1982 ABANO ANTHONY 27 11/16/1978 ABASCAL ARMANDO 71 03/04/1984 Page 1 of 499 09/18/2014 DOC Hart Island Burial Records Based on DOC Hart Island Burial Records Place of Death NEW YORK PRESBYTERIAN HOSPITAL/THE ALLEN HOSPITAL HARLEM HOSPITAL CENTER 119 E. 29TH ST CABRINI MEDICAL CENTER LAGUARDIA HOSPITAL ST. CLARE'S HOSPITAL AND HEALTH CENTER BRONX-LEBANON HOSPITAL CENTER INTERFAITH MEDICAL CENTER JACOBI MEDICAL CENTER MARY IMMACULATE HOSPITAL 683 E 140 ST OUR LADY OF MERCY MEDICAL CENTER NEW YORK PRESBYTERIAN HOSPITAL MOUNT SINAI HOSPITAL CALVARY HOSPITAL BOOTH MEMORIAL HOSPITAL BETH ISRAEL MEDICAL CENTER 132 SECOND AVE 520 W. 157TH STR. Page 2 of 499 09/18/2014 DOC Hart Island Burial Records Based on DOC Hart Island Burial Records ABASICKORY DANIEL 71 05/28/2008 ABASIDZE RASOL 55 05/15/1985 ABASS SAWSON 02/14/1989 ABAYA JULIO 52 09/02/1992 ABB JAMES 40 07/22/1979 ABBAJAY MARGERY 84 01/08/2003 ABBOT JOSEPH 86 03/12/1993 ABBOTT 03/14/1990 ABBOTT 03/14/1990 ABBOTT ANGEL 09/18/1997 ABBOTT BARBARA 40 12/29/1997 ABBOTT KEESHA 28 11/18/1998 ABBRUZZESE ANN 79 03/01/2013 ABDALLA NEAMA 09/15/2005 ABDALLAH FAIKA 11/30/1988 ABDATIELLO JOHN 54 06/02/2003 ABDELLI ALDJIA 03/01/2001 ABDELRAHIM AWATIF MOHAMED 07/16/2006 ABDELUHACEK ELMAN SMIRIN 08/08/2005 ABDI 07/09/1985 ABDOOL 12/19/1984 Page 3 of 499 09/18/2014 DOC Hart Island Burial Records Based on DOC Hart Island Burial Records FIELDSTON LODGE NH MAIMONIDES MEDICAL CENTER LUTHERAN MEDICAL CENTER BELLEVUE HOSPITAL CENTER SYDENHAM HOSPITAL ST. -

A N D R E W S T E

THEISSUE #195: APRIL 1–30, 2014 INDYPENDENT A FREE PAPER FOR FREE PEOPLE DON’T FRACK WITH US A CANADIAN COMMUNITY RESISTS RUNAWAY GAS DRILLING By Michael Premo & Andrew Stern, p12 ANDREW STERN SCHOOL TESTING VENEZUELA ON EDGE REVOLT PEACE POETS KNOW IT p16 p10 p19 the reader’s voice THE INDYPENDENT question of whether these leaders vor of cutting taxes for the 1% and faction to admit that I exist, let THE INDYPENDENTISSUE #194: FEBRUARY 25–MARCH 24, 2014 also support Bratton’s longstand- their multinational conglomerate alone write an article about me A FREE PAPER FOR FREE PEOPLE ing commitment to the “broken monopolies, as well as the bloated (“White Men’s Rage,” February/ THE INDYPENDENT, INC. windows” theory of policing that budget for imperialist war monger- March Indypendent). Low-income 388 Atlantic Avenue, 2nd Floor people who commit minor “qual- ing and Constitution shredding. urban white people are 2 percent Brooklyn, NY 11217 ity-of-life” offenses are the most of the population by the way. We 212-904-1282 www.indypendent.org likely ones to eventually commit — Kevin Schmidt, are never allowed to talk about Twitter: @TheIndypendent serious offenses and his emphasis from indypendent.org anything, because the issues that facebook.com/TheIndypendent on predictive policing — philoso- effect us are assumed to be “black” phies that have disproportionately KEYSTONE XL HELL issues. BOARD OF DIRECTORS: REFORMING THE NYPD targeted communities of color for It is my opinion that the Keystone — John Novak, Ellen Davidson, Anna Gold, AFTER THEIR STOP-AND-FRISK WIN, REFORM ADVOCATES PRESS FOR MORE CHANGES. -

VIP Prime Richmond

2021 Medicare VIP Prime HMO and HMO-POS Provider Directory RICHMOND This page is intentionally left blank. EmblemHealth Medicare VIP Prime HMO and HMO-POS Provider Directory This directory is current as of 08/02/2021. This directory provides a list of EmblemHealth Medicare VIP Prime HMO and HMO-POS current network providers. This directory is for Richmond County. To access our plan’s online provider directory, you can visit emblemhealth.com/ medicare. For any questions about the information contained in this directory, please call our Customer Service Department at 877-344-7364, 8 am to 8 pm, seven days a week. TTY users should call 711. EmblemHealth Plan, Inc., EmblemHealth Insurance Company, EmblemHealth Services Company, LLC and Health Insurance Plan of Greater New York (HIP) are EmblemHealth companies. EmblemHealth Services Company, LLC provides administrative services to the EmblemHealth companies. This document may be available in alternate formats such as large print and Braille. Y0026_201155_C i EmblemHealth Medicare VIP Prime HMO and HMO-POS Provider Directory Section 1 – Introduction This directory provides a list of our plan’s VIP Prime network providers. To get detailed information about your health care coverage, please see your Evidence of Coverage (EOC). Please read this section if you are a member of EmblemHealth VIP Premier (HMO) Group and EmblemHealth Group Access Rx (PPO). You will have to choose one of our network providers listed in this directory to be your Primary Care Provider (PCP). Generally, you must get your health care services from your PCP. The term “PCP” will be used throughout this directory. -

The Emergency Medical Services Reform Act of 1983

THE RIGHTS OF THE UNINSURED IN NEW YORK CITY TRAINING MANUAL 2002 By New York Lawyers for the Public Interest, with input from the Commission on the Public’s Health System. Special thanks to the Commonwealth Fund for its support of this project. TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface . iv I. Emergency Medical Services: Getting to the Hospital . .1 Supplement I-A New York City Trauma Centers Supplement I-B List of Permanent Hospital Diversion II. Access at Private and Public Facilities: Patients’ Rights to Emergency Care . 13 Supplement II-A Sample Statement of Deficiencies and Plan of Correction for St. Lukes- Roosevelt Hospital III. Health and Hospitals Corporation: Patients’ Rights at New York City’s Public Hospitals and Clinics . 45 Supplement III-A HHC Facility Addresses and Phone Numbers Supplement III-B HHC Patient Relations Offices Supplement III-C New HHC Plus Program Supplement III-D Adult Fee Scale for Outpatient Services Supplement III-E Fee Scale for Ambulatory Surgery Supplement III-F Fee Scale for Inpatient Services Supplement III-G NYS Patients’ Bill of Rights Supplement III-H HHC Executive Order No 29 Supplement III-I Basic Collection Advice for Low-Income People IV. Hill-Burton Facilities: Patients Rights at Facilities in Receipt of Hill-Burton Funding . 87 Supplement IV-A NYC Uncompensated Care Facilities (20 years) Supplement IV-B NYC Uncompensated Care Facilities (Forever) Supplement IV-C Where to Send Complaints Supplement IV-D NYC Community Services Facilities V. Civil Rights at Public and Private Health Care Facilities . .109 VI. Appendices . 115 - ii - A. New York City District Attorney’s Offices B. -

Health Occupations Training Programs Administered by Hospitals: a Directory

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 114 495 CE 005 176 TITLE Health Occupations Training Programs Administered by Hospitals: A Directory. INSTITUTION Health Resources Administration (DHEW/PHS), Bethesda, Md. Bureau of Health Resources Development. REPORT NO DHEW-HRA-75-27 PUB DATE Oct 73 NOTE 958p. EDRS PRICE MF-$1.55 HC-$48.88 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS *Directories; *Educational Programs; *Health Occupations Education; National Surveys; Questionnaires ABSTRACT A directory of 4,013 hospital-administered allied health and nursing programs throughout the United States is presented in the document. Section 1, Guide to Training Programs, is designed for guidance counselors, students, and health planners. It contains an alphabetical listing of training programs within major occupational categories and provides information on program length, educational entrance requirements, and number of graduates. Section 2, Guide to Hospitals Having Training Programs, is designed for hospital administrators and health planners. It presents an alphabetical listing of hospitals having training programs by state and by city and provides information regarding the individual hospitals. Both sections are preceded by explanatory notes and a table of contents. The four-part appendix includes:(1) Screener Questionnaire, part 1 of the survey sent to hospitals;(2) Detailed Program Questionnaire, part 2 of the survey;(3) Glossary of Occupational Titles, a compilation of terms used in the document; and (4) Titles of Programs, Reported by Respondent Hospitals, not contained in the above glossary. An index lists all hospital training programs included in the directory. (LH) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available.