Video and Transcript of 25 Years Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020JAN Yr 12 PAL ATAR Course Mapped to the FBLEP.Docx

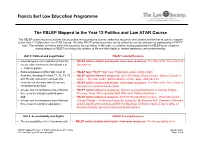

Francis Burt Law Education Programme The FBLEP Mapped to the Year 12 Politics and Law ATAR Course The FBLEP online resources include classroom/pre and post-visit resources, reference resources and student and teacher resources mapped to the Year 12 Politics and Law ATAR Course. All of the FBLEP online resources can be utilised by schools that are not participating in FBLEP visits. The activities and tasks within the resources are not reliant, in the main, on students having participated in FBLEP tours. However, participating in a FBLEP tour brings the syllabus to life and adds depth to student awareness and understanding. Unit 3: Political and Legal Power FBLEP Activity/Resource • Lawmaking process in parliament and the • FBLEP online student and teacher classroom resources: The Role of the Three Arms of courts, with reference to the influence of Government • Political parties • Roles and powers of the High Court of • FBLEP tour: FBLEP High Court Programme (when sitting in WA) Australia, including Sections 71, 72, 73, 75 • FBLEP online reference resources: 2010 Sir Ronald Wilson Lecture: ‘Being a Chapter 3 and 76 with reference to at least one Judge’ – The Hon. Justice Michael Barker, Lecture paper and Video file common law decision and at least one • FBLEP online student and teacher classroom resources: The Role of the Three Arms of constitutional decision Government (constitutional decision) • at least one contemporary issue (the last • FBLEP online reference resources: Non-Consensual Distribution of Intimate Images three years) relating -

Biotech Daily

Biotech Daily Tuesday September 8, 2009 Daily news on ASX-listed biotechnology companies * ASX, BIOTECH UP: CATHRX UP 11%; COMPUMEDICS DOWN 9.5% * SIRTEX’S DR BRUCE GRAY WINS ‘NO DUTY TO INVENT’ CASE * SPRUSON & FERGUSON: IP GENIE UNBOTTLED * BIONOMICS RAISES $12.8m; SHARE PLAN TO RAISE $2.2m * MEDICAL THERAPIES’ MIDKINE BOOSTS BREAST CANCER TESTS * UNDERWRITER PNK HOLDINGS TAKES 31% OF PATRYS * CATHRX APPOINTS MERCE V SPANISH DISTRIBUTOR MARKET REPORT The Australian stock market climbed 1.56 percent on Tuesday September 8, 2009 with the S&P ASX 200 up 69.4 points to 4523.8 points. Sixteen of the Biotech Daily Top 40 stocks were up, 13 fell, seven traded unchanged and four were untraded. Cathrx was best, climbing four cents or 11.43 percent to 39 cents with 185,310 shares traded, followed by Antisense up 0.4 cents or 8.9 percent to 4.9 cents. Bionomics climbed 6.25 percent; Cellestis, Novogen and Sirtex were up more than four percent; Acrux and Viralytics were up more than three percent; Benitec, Cochlear and Optiscan rose more than two percent; with Biota, Chemgenex, Mesobalst, Nanosonics and Psivida up more than one percent. Compumedics led the falls, down two cents or 9.5 percent to 19 cents with 60,000 shares traded, followed by Cytopia down one cent or 7.7 percent to 12 cents. Tissue Therapies and Universal Biosensors lost more than six percent; Prana fell 4.35 percent; Clinuvel fell 3.2 percent; Circadian, Pharmaxis, Progen and Sunshine Heart shed two percent or more; with Genera and Starpharma down more than one percent. -

Sir Ronald Wilson Lecture (Pdf 102Kb)

SIR RONALD WILSON LECTURE 19 MAY 2011 The Hon Justice Murray, Senior Judge, Supreme Court of WA THE DELIVERY OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE: BUILDING ON THE PAST TO MEET THE CHALLENGES OF THE FUTURE INTRODUCTION Mr President, distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen. It is a very great honour to have been asked to deliver the Sir Ronald Wilson Lecture this year, although I appreciate that I am very much the second choice, and that I only got the gig because his Honour the Chief Justice is in Europe, attending a Court of the Future Program on courthouse design in the perhaps over-optimistic expectation that what he learns will be useful when, or if, the Supreme Court is provided with new accommodation of an appropriate standard to go with the 1903 Courthouse and to replace our tenancy in the former Royal Commission into WA Incorporated premises in an office building in the city. Of course, the mention of those premises recalls another link to Sir Ronald Wilson who, with the Hon Justice Kennedy, seconded from the Court, and the then recently retired judge, the Hon Peter Brinsden QC, served on that Royal Commission, which made such momentous findings on a wide range of Government activities and the people involved in them. I feel particularly intimidated when I observe that previous presenters of this lecture include people such as Sir Ronald himself, the Rt Hon Lord MacKay of Clashfern, the Rt Hon Sir Ninian Stephen, the Rt Hon Sir Zelman Cowen, Justice Michael Kirby, as he then was, and others, including local luminaries, the Hon Justice Robert French, as he then was, the Hon Justice Carmel McLure, Chief Judge Antoinette Kennedy, and the Hon Justice Michael Barker. -

Legislative Assembly

Legislative Assembly Thursday, 14 August 2003 THE SPEAKER (Mr F. Riebeling) took the Chair at 9.00 am, and read prayers. AUSTRALIA BUSINESS ARTS FOUNDATION AWARDS Statement by Minister for Culture and the Arts MS S.M. McHALE (Thornlie - Minister for Culture and the Arts) [9.02 am]: I bring to the attention of the House Western Australia’s success in the recent Australia Business Arts Foundation Awards presented on 7 August 2003. The awards this year attracted nominations from 107 partnerships, which is the highest number received to date. Forty of those nominations were from Western Australia, and seven of the 27 finalists were from our State. It is pleasing to note that three of the nine national categories, and the Richard Pratt Business Leadership Award, were won by Western Australians. I congratulate Janet Holmes a Court on receiving the Richard Pratt Business Leadership Award. Members will be aware that Janet joins previous winner Michael Chaney in being presented this award in recognition of business leadership in support of the arts. I also congratulate Alcoa World Alumina on winning the Caliburn Corporate Strategy Award. This award recognises companies that are implementing strategies to maximise returns on their arts partnerships. The SPEAKER: Order, members! The background noise from other conversations means that I am having difficulty hearing the minister. Ms S.M. McHALE: Thank you, Mr Speaker. Alcoa World Alumina has successfully linked its arts partnerships with what the company is trying to do as a whole, and has integrated its corporate objectives with the needs of its arts partners. -

Transcript: Welcome Ceremony For

Copyright in this document is reserved to the State of Western Australia. Reproduction of this document (or part thereof, in any format) except with the prior written consent of the Attorney General is prohibited. Please note that under section 43 of the Copyright Act 1968 copyright is not infringed by anything reproduced for the purposes of a judicial proceeding or of a report of a judicial proceeding. THE SUPREME COURT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA WELCOME TO THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE McGRATH FULL BENCH TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS AT PERTH ON MONDAY, 28 NOVEMBER 2016, AT 9.15 AM JSS SC/CIV/PE/ MARTIN CJ: The Court sits this morning to welcome the Honourable Justice Joseph McGrath to the Court. His Honour took the oath of office and received his commission as a judge of the General Division at Government House last Friday. I would like to particularly welcome members of his Honour's family to this morning's sitting including his Honour's children, Thomas and Genevieve, his parents-in-law John and Carolyn Pritchard, and his sister and brother-in-law, Nanette Pritchard and Chris Cook, the latter of whom have travelled from the ACT to join us here this morning. I would also like to welcome the Honourable Malcolm McCusker AC CVO QC, former Governor of Western Australia, the Honourable Justices Tony Siopis, Michael Barker and James Edelman of the Federal Court of Australia, his Honour Chief Judge Kevin Sleight of the District Court, his Honour Judge Denis Reynolds, President of the Children's Court, Chief Magistrate Steven Heath and Ms Pauline Bagdonavicius, the Acting Director General of the Department of the Attorney General, and other distinguished guests, including many past members of this and other Courts. -

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

14 July 2014 The Executive Director Australian Law Reform Commission GPO Box 3708 Sydney NSW 2001 [email protected] AIATSIS submission to Australian Law Reform Commission Review of the Native Title Act Issues Paper 45 of March 2014 The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) welcomes the opportunity to provide input to the Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) in its review into the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA). AIATSIS is one of Australia’s publicly funded research agencies and is dedicated to research across the broad spectrum of native title law, policy and practice and where possible, this submission draws on this broad evidence base. AIATSIS includes the Native Title Research Unit (NTRU), established following the Mabo decision. Through the NTRU, AIATSIS seeks to promote the recognition and protection of the native title of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples through independent research and assessment of the impact of policy and legal developments. In our response, AIATSIS has sought to promote a principled approach to reform. We have sought to highlight the primary underlying principle that Indigenous peoples have a right to own and inherit their traditional territories; to make decisions about, and benefit from, their traditional territories and resources; as well as to maintain their culture. The importance of the recognition and protection of native title to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the broader Australian community cannot be overstated. We appreciate that the ALRC’s review of the NTA, and any government response to subsequent recommendations, is intended to enhance the opportunity for addressing and reducing barriers to the recognition of native title while providing greater certainty in the way native title interacts with other interests in land and 1 waters. -

Past As Prologue : the Royal Commission Into Commercial Activities of Government and Other Matters : Proceedings from a Conferen

Edith Cowan University Research Online ECU Publications Pre. 2011 1994 Past as prologue : the Royal Commission into Commercial Activities of Government and Other Matters : proceedings from a conference on the Part II Report of the Royal Commission and the reform of government in Western Australia Mark Brogan (Ed.) Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks Part of the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Brogan, M., & Phillips, H. (1994). Past as prologue : the Royal Commission into Commercial Activities of Government and Other Matters : proceedings from a conference on the Part II Report of the Royal Commission and the reform of government in Western Australia. Mount Lawley, Australia: SASTEC, Adith Cowan University. This Conference Proceeding is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks/7001 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). -

The Role of Judges in Making Law

School of Law The Honourable David Malcolm Annual Memorial Lecture The Honourable Justice Michael Barker, Federal Court of Australia Perth The Role of Judges in Making Law Thursday 26 October 2017 | 6-7pm followed by refreshments The Honourable Justice Barker was appointed to the Federal Court of Australia in February 2009. At the time of his appointment he was a Judge of the Supreme Court of Western Australia (appointed August 2002) and President of the WA Statefollowed by refreshments ThursdayAdministrative Tribunal (appointed20 October December 2004). 2016 | 6-7pm Justice Barker holds the degrees LLB (Hons) (UWA) and LLM (York University, Canada). He was admitted to practice in Western Australia in December 1973. After practising as a barrister and solicitor in Perth he undertook postgraduate studies in Canada. He was a member of the Faculty of Law, Australian National University, Canberra 1981 – 1985 before returning to Perth to practice. He joined the independent Bar in Perth in 1993. In 1991 – 1992, Justice Barker was one of the counsel assisting the 'WA Inc' Royal Commission. In 1990 – 1994 he was Chairman of the WA Town Planning Appeals Tribunal. He took silk in 1996. Venue: The University of Notre Dame Australia Michael Keating Room (ND42) Cliff Street, Fremantle RSVP: Pam Meehan on 9433 0741 or email [email protected] The Honourable David Malcolm Memorial Lecture series was established in 2015 by the School of Law (Fremantle) to honour the late David Malcolm, a former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Western Australia. The annual Memorial Lecture is dedicated to his life and work as an eminent jurist, scholar and legal practitioner as well as the significant contributions he made to the law profession, community and civil society. -

Meeting Booklet FOM 2014

Convocation FIRST ORDINARY MEETING Convocation welcomes all graduates and other members of Convocation to the First Ordinary Meeting Friday 21 March 2014 at 6pm at the Banquet Hall, The University Club of Western Australia Guest Speaker: Winthrop Professor Carmen Lawrence ‘An avalanche of change: Will universities as we know them survive the onslaught?’ Agenda The First Ordinary Meeting of the Convocation of The University of Western Australia will take place at 6pm Friday 21 March 2014 in The University Club of Western Australia 1. Minutes of the Second Ordinary Meeting held on Friday 20 September 2013 (Attachment A) 2. Amendments and motion of acceptance of minutes 3. Business arising from the minutes 4. Correspondence 5. Results of Convocation Elections for Warden, Deputy Warden, Convocation-elected Members of the UWA Senate and Members of the Council of Convocation 6. Vice-Chancellor’s report (Attachment B) 7. Guild President’s report (Attachment C) 8. Warden’s report (Attachment D) 9. Convocation Officer’s report (Attachment E) 10. Other business Guest Speaker Winthrop Professor Carmen Lawrence will talk on: ‘An avalanche of change: Will universities as we know them survive the onslaught?’ Further copies of all meeting materials are available on the Convocation website at convocation.uwa.edu.au The University of Western Australia | 01 Minutes Minutes of the Second Ordinary Meeting of Convocation 20 September 2013 The Second Ordinary Meeting of Convocation was held Marie Ryan, Djohan Salim, Angela Samec, Joan Sandover, on Friday 20 September 2013 at 6pm in The University Club Penelope Sandover, John Sanusi, Jennifer Searcy, James of Western Australia. -

Farewell to the Honourable Justice Murray

10/1/sjr Farewell THE SUPREME COURT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA FAREWELL TO THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE MURRAY TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS AT PERTH ON THURSDAY, 7 DECEMBER 2011, AT 4.29 PM 7/12/11 1 (s&c) Spark & Cannon 10/2/sjr Farewell THE ORDERLY: Please remain standing for his Excellency the Governor Mr McCusker, and Mrs McCusker. Please be seated. MARTIN CJ: The Court sits today to farewell the Honourable Justice Michael Murray who will officially retire from office on 15 January 2012. I would like to particularly welcome today and in a warm way members of his Honour's family, including his wife Dale, their children Timothy, Christopher and Abigail, daughter-in- law Samantha and grandchildren Ben, Isaac, Sarah and Emma, although apparently Max and Zachary are not able to be with us, his Honour's stepmother Mrs Margaret Murray, and his brothers David and Robert Murray. Unfortunately, his Honour's brother Mr Richard Murray is unable to be present today, but I would also particularly like to welcome his Honour's brother-in-law Dr Peter Randell and Mrs Gail Randell and his Honour's niece Lindy Murray. I would also like to warmly welcome the Governor of Western Australia, his Excellency Mr Malcolm McCusker AO QC, and Mrs Tonya McCusker, their Honours Justices Siopis, John Gilmour and Michael Barker of the Federal Court of Australia, Justice Stephen Thackray, Chief Judge of the Family Court of Western Australia, his Honour Judge Peter Martino, Chief Judge of the District Court of Western Australia, and the many current members of the District Court who are with us today, President Denis Reynolds of the Children's Court and her Honour Deputy Chief Magistrate Libby Woods, Ms Cheryl Gwilliam, Director-General of the Department of the Attorney-General, and many other distinguished guests too numerous to name, including former members of this and other courts. -

The Constitutional Centenary Foundation

Chapter Seven White Anting the Constitution : The Constitutional Centenary Foundation John Stone Copyright 1994 by The Samuel Griffith Society. All rights reserved. When I came to finalize for printing the program for this Conference, I asked myself whether I should retain the title given to this paper when issuing preliminary Conference details, or whether I should amend it in one small, but important, particular. Rather than the title White-Anting the Constitution : The Constitutional Centenary Foundation, I asked myself whether its first portion should read White-Anting the Constitution?, with the question mark signifying that, so to speak, the jury was still out. In its very nature, of course, the evidence in the matter can only be circumstantial, and on the basis of it different jurors may possibly arrive at different conclusions. Moreover, it is almost certainly the case that the motivations of some of those involved with the Foundation differ from those of others, so that any verdict is unlikely to apply to all of them, and will also apply in differing degrees even among those who might be placed in one camp or the other. In these circumstances, all that can be done is to marshall the evidence (or as much of it as is publicly available), do one's level best to assess it objectively, and arrive at as balanced a conclusion as possible. I can only say that, after having undertaken that process, I have decided to leave the preliminary title unchanged. There is an American saying to the effect that "if it looks like a duck, waddles like a duck, and quacks like a duck", then it's almost certainly a duck. -

Reflections on an Australian Aboriginal Treaty 1986–2006

What Good Condition? What Good Condition? Reflections on an Australian Aboriginal Treaty 1986–2006 Aboriginal History Monograph 13 Edited by Peter Read, Gary Meyers and Bob Reece �������������������������������� �������������������������������� ������������������������������� � �������������������������������������������������������������� � �������������������������������������������������������������� �� ��������������������������������������������������� ��� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������� � ���������������������������� � �������������������(pbk)������� � ������������������������������������� � ��������������������������� � ����������������������������������������������������� � ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ��� � ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� � � ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� � � �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� � � ������������������������������������������ ��������������������������������� � �������������������� � ���������� � ���������� ���������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������