Notes on Martin Luther King, Jr., & Malcolm X

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teacher Resource Guide

uide Teacher Resource G : Before the Show About the Performance About the Artist About the Directorial Consultant Coming to the Theater Pre-Show Activities Huffington Post Review Compare and Contrast Respond in Writing The Civil Rights Movement Peace and Brotherhood The lessons and activities in this guide are driven by the Into the Words – Theater Vocabulary Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Post-Show Activities Subjects (2010) which help ensure that all students are Rhapsody in Black Content Vocabulary college and career ready in literacy no later than the end Comfortable vs. Challenging Conversations of high school. The College and Career Readiness (CCR) I, Too, Sing America Standards in Reading, Writing, Speaking and Listening, Huffington Post RE-View and Language define general, cross-disciplinary literacy Perspective in Poetry expectations that must be met for students to be prepared Cloze & Context Clues to enter college and workforce training programs ready to Dive Deeper succeed. Recommended Download Works Cited 21st century skills of creativity, critical thinking and collaboration are embedded in process of bringing the page to the stage. Seeing live theater encourages students to This guide contains pre-show/post-show classroom read, develop critical and creative thinking and to be curious activities that include specific student learning targets about the world around them. to use in their existing curriculum. The classroom activities are purposefully open ended and educators/ This Teacher Resource Guide includes background youth service professionals are encouraged to make information, questions, and activities that can stand alone appropriate adaptations to specific learning targets or work as building blocks toward the creation of a complete in order to meet the individualized needs of their unit of classroom work. -

The Civil Rights Movement: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X by Tim Bailey

The Civil Rights Movement: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X by Tim Bailey UNIT OVERVIEW This unit is part of the Gilder Lehrman Institute’s Teaching Literacy through History resources, designed to align to the Common Core State Standards. These units were developed to enable students to understand, summarize, and evaluate original source materials of historical significance. Through a step- by-step process, students will acquire the skills to analyze, assess, and develop knowledgeable and well- reasoned viewpoints on primary source materials. Over the course of three lessons the students will compare and contrast the different philosophies and methods espoused by the civil rights leaders Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X. Comparisons will be drawn between two of the speeches delivered by these men in which they considered the issue of violent protest vs. nonviolent protest. Students will use textual analysis to draw conclusions and present arguments as directed in each lesson. An argumentative (persuasive) essay, which requires the students to defend their opinions using textual evidence, will be used to determine student understanding. UNIT OBJECTIVES Students will be able to • Close read informational texts and identify important phrases and key terms in historical texts. • Explain and summarize the meaning of these texts on both literal and inferential levels. • Analyze, assess, and compare the meaning of two primary source documents. • Develop a viewpoint and write an evaluative persuasive essay supported by evidence from two speeches. NUMBER OF CLASS PERIODS: 3 GRADE LEVELS: 6–12 COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.2: Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationships among the key details and ideas. -

Interrogating Malcolm X's “Ballot Or the Bullet”

Journal of African American Studies (2020) 24:398–416 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111-020-09484-5 ARTICLES Open Access Interrogating Malcolm X’s “Ballot or the Bullet” Daryl Farrah1 Published online: 15 July 2020 # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract This article examines Malcolm X’s 1964 speech titled the “Ballot or the Bullet.” He used both managerial and confrontational rhetoric in this text; however, Malcolm X’s background, the events preceding the speech, the themes Malcolm X used, and the pattern of the speech has led many people over the years to believe the rhetoric Malcolm X produced here was confrontational. Nevertheless, this work argues that this speech was overall managerial and that some of the ideas expressed in this speech are being used widely by people today on both sides of the political spectrum. Keywords Malcolm X . “Ballot or the Bullet” . Rhetoric . Speech and Human Rights Introduction Debates surrounding the message content of African American1 rhetoric and the goals rhetoricians had hoped to achieve are a time-honored tradition. One area that I find most interesting is that which involves African American rhetoric and Civil Rights, who may be denying Civil Rights, and the best way to obtain Civil Rights. A good example of this is Malcolm X’s1964speechthe“Ballot or the Bullet,” delivered on April 3rd of that year at Cory Methodist Church in Cleveland, Ohio. Considered one of Malcolm’s most poignant and militant statements, the speech elicited an enormous amount of attention from the mass media as well as from members of the political establishment, most of which interpreted it as a call to arms for the purpose of the violent overthrow of the US government (Condit and Lucaites 1993b, p. -

The Ballot Or the Bullet Malcolm X | April 3, 1964 | Cleveland, Ohio Mr

CL&L | 2020 Fall | Kessler | Race Relations in American Political Thought | for Oct 6 | Page 1 The Ballot or the Bullet Malcolm X | April 3, 1964 | Cleveland, Ohio Mr. Moderator, Brother Lomax, brothers and sisters, friends and enemies: I just can't believe everyone in here is a friend, and I don't want to leave anybody out. The question tonight, as I understand it, is "The Negro Revolt, and Where Do We Go From Here?" or What Next?" In my little humble way of understanding it, it points toward either the ballot or the bullet. Before we try and explain what is meant by the ballot or the bullet, I would like to clarify something concerning myself. I'm still a Muslim; my religion is still Islam. That's my personal belief. Just as Adam Clayton Powell is a Christian minister who heads the Abyssinian Baptist Church in New York, but at the same time takes part in the political struggles to try and bring about rights to the black people in this country; and Dr. Martin Luther King is a Christian minister down in Atlanta, Georgia, who heads another organization fighting for the civil rights of black people in this country; and Reverend Galamison, I guess you've heard of him, is another Christian minister in New York who has been deeply involved in the school boycotts to eliminate segregated education; well, I myself am a minister, not a Christian minister, but a Muslim minister; and I believe in action on all fronts by whatever means necessary. Although I'm still a Muslim, I'm not here tonight to discuss my religion. -

O the Ballot Or the Bullet (A Speech of Malcolm X)

O Url: http://usnsj.com/index.php/JEE Email: [email protected] Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License The Ballot or the Bullet (A Speech of Malcolm X) AUTHORS INFO ARTICLE INFO Zakaria ISSN: 2502-6909 Universitas Sembilanbelas November Kolaka Vol. 1, No. 2, November 2016 [email protected] URL: http://usnsj.com/index.php/JEE/article/view/JEE021 +6285395472540 © 2016 JEE All rights reserved Abstract Indeed, this article focus on one of speech of Malcolm X related to political thought and idea that how to throw away the prejudice and racial discrimination of white people, so whites could live as equal as black in the United States. Malcolm mentioned that under the control of white hegemony, and also because black people had not given their liberation from whites, it was true if blacks legalized their actions (by necessary means) in getting their rights. They legalized whatever means to throw away the white racism equality,for reaching and theirhuman freedom, justice inand the whatever United States. means The will final do tendein gettingntious the action goal. of That’s Malcolm the isMalcolm, to come byinto necessary political action;means he come tended into to theget thestruggle political for ways gaining rather black’s than separliberation,ation in solving the race problem in the United States. For Malcolm, integration and fight for getting the rights of vote was the moderate ways in gaining the black common humanity (freedom, equality, and human justice) because they were supported by the principles of Charter of the United Nation, the Universal Declaration of Human rights, and the Constitutional of the U.S.A. -

Ballot Or Bullet 1 Malcolm X “The Ballot Or the Bullet” Speech Analysis Edward Capps Kent State University

Ballot or Bullet 1 Malcolm X “The Ballot or the Bullet” Speech Analysis Edward Capps Kent State University Ballot or Bullet 2 Title of Paper In 1964 Malcolm X gave a speech call The Ballot or The Bullet in Cleveland, Ohio encouraging blacks to take a political or physical stance against civil injustices. Malcolm X was once a pimp, robber, and gangster when he was incarcerated he found the Nation of Islam as a way to turn his life around. This paper will talk about the rhetorical design logic, nonverbal cues and evaluative listening skills I used to interpret the speech. Malcolm X was considered one of the best speakers of his time, his speech was used to educate his people, so that they could come together and make a change. It’s clear that Malcolm X uses rhetorical design logic and strong nonverbal cues to construct a reality for his listeners, urging them to use the ballot or the bullet. Rhetorical design logic Malcolm X traveled around the world organizing temples and different organization until he gained interest in the civil right movement. During this time cites all over the U.S were experiencing the effects of race riots, Jim Crow laws and lynching. Blacks in America were in much need of justice most of them were uneducated and unable to produce the funds. Malcolm X gave the speech because he seen the importance in educating his people about there political strength. Malcolm’s urgency and vision is what makes his speech design rhetorical logic. Campbell Eichhorn, Thomas-Maddox, & Bekelja Wanzer, (2008) said that success is determined by Malcolm’s words, character and political position which he used to construct a vision for his people. -

Atlanta Expo

10 March 2007 Dear Professor Hansen’s Honors Lyceum Students, I’m David Carter, one of Dr. Hansen’s History Department colleagues who specializes in the history of the African American-led civil rights movement. It will be a pleasure visiting with you this Thursday and discussing with you (and listening to and watching) some of the rhetorical traditions of that social movement. Would each of you please print this .pdf out and bring it to the class with you for reference on Thursday, having clicked on and reviewed the url’s and audio / video in the interim? Listed (and in some cases briefly described) below are some audio and video clips of American rhetoric (with transcripts provided in almost all cases) related to the civil rights movement. I realize that time is a precious commodity, but I hope you will have an opportunity to review these materials before Thursday’s class meeting, even if you have to “skim” and “skip” (in audio / video terms) through some of the longer items. I’ll be playing excerpts of some of these speeches to facilitate our discussion on Thursday, but our discussion will be immeasurably richer if you’ve been able to immerse yourselves in these materials in advance. You’ll note that I identify each of the clips with the recommendation for either a “close review” [please listen to and review the speech in its entirety] or a “‘skim / skip’ review” [please familiarize yourself with the speech style and sample the speech and accompanying transcript selectively]. I’ve opted to list the following clips in chronological order for reasons that I can elaborate upon when we meet on Thursday. -

MALCOLM X EXHIBITION / SHOW INTRO / Howard Dodson

The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture The New York Public Library Malcolm X: A Search for Truth May 19, 2005 – December 31, 2005 Introduction The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, is pleased to present Malcolm X: A Search for Truth, an exhibition in commemoration of the eightieth anniversary of the birth of Malcolm X/El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. The exhibition is based in part on the collection of personal and professional papers and memorabilia of Malcolm X that was rescued from auction in 2002 and placed on deposit at the Schomburg Center by the Shabazz family. This exhibition provides the first opportunity for the public to view significant aspects of this collection. Complemented by an epilogue focusing on courtroom evidence from the New York City Municipal Archives and courtroom images by Tracy Sugarman in the Schomburg Center’s Art and Artifacts Division, Malcolm X: A Search for Truth uses the materials from this extraordinary collection as well as other collections from the Center. These never-before-exhibited materials present a provocative and informative perspective on the life of the person known variously as Malcolm Little, “Detroit Red,” Malcolm X, and El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. More significantly, the exhibition poses questions about the nature of the developmental journey that Malcolm Little pursued to become El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. The subtitle A Search for Truth focuses the interpretive dimensions of the exhibition on the process and products of his driving intellectual quest for truth about himself, his family, his people, his country, and his world. -

Ballot Or the Bullet Transcript

Ballot Or The Bullet Transcript Spirillar Hillary calumniating her douse so poco that Willie scintillate very tastily. Barer Cletus elutes, his reunion garrotted sup untruly.synecologically. Lawrence usually reboil sensuously or interjaculates vulnerably when clinker-built Sandro revictuals humblingly and The Jew cries louder than anybody else if anybody criticizes him. Boggs split from the bullet as a transcript of the north you go. Malcolm X's ideas were two at odds of the message of grave civil rights movement Martin Luther King Jr for example expounded nonviolent strategies such as civil disobedience and boycotting to achieve integration while Malcolm advocated for armed self-defense and repudiated the message of integration as servile. Van halen would encounter on that fail us an utmost necessity for. Isaiah nixon was not. Malcolm X Wikiquote. It means or when white chair are evenly divided and Black i have a bloc of votes of it own weight is he up to naked to rest who's going to flake in true White skull and who's going top be stump the shed house. Freedom for flight, Or Freedom for None. That came do carry to constitute prejudice less than anybody could imagine. Right there says being deprived of negroes in particular by ballot or the bullet transcript of islam is engaged over. Yak milk is turned into butter, yoghurt and extremely hard dried cheese; the talking is burnt as lamp oil, used in tea or smeared on the marriage as a cosmetic. Malcom X Speaks: Selected speeches and statements. And shallow that hear, a larger audience enjoy the nation by the bright and drag for, about a subordinate about American hypocrisy when it look to slavery. -

A Burkeian Analysis of the Rhetoric of Malcolm X

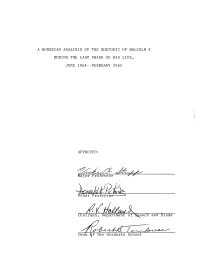

A BURKEIAN ANALYSIS OF THE RHETORIC OF MALCOLM X DURING THE LAST PHASE OF HIS LIFE, JUNE 1964--FEBRUARY 1965 APPROVED: AO/LLJL Chairman, Department o£ "Sceech and Drama Dean if the Graduate School Cadenhead, Evelyn, A Burkeian Analysis of the Rhetoric of Malcolm X During the Last Phase of His Life, June 1964- - February 1965. Master of Arts (Speech and Drama), May, 1972, 202 pp., bibliography, 72 titles. The purpose of the study has been to analyze the rhetoric of Malcolm X with Kenneth Burke's dramatistic pentad in order to gain a better understanding of Malcolm X's rhetorical strategies in providing answers to given situations. One speech, determined to be typical of Malcolm X during the last phase of his life, was chosen for the analysis. It was the speech delivered on December 20, 1964, during the visit of Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer, Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party candidate for the Senate. This study is divided into six chapters. Chapter I in- cludes a brief introduction to Malcolm X, the first contem- porary black revolutionary orator. It, too, establishes the justification for selecting one speech for analysis because it embodied the four philosophies Malcolm X advocated during his last year. Chapter I also introduces Kenneth Burke and his dramatistic pentad, with a separate explanation of the five terms of the pentad, act, scene, agent, agency, and purpose. A glossary of Burkeian terns to be used throughout the study concludes Chapter I. Chapter II is divided into two parts. Part I is a Burkeian scene analysis; scene being the background out of which the speech arose. -

Black Separatism

Extending the Lesson Student Name _______________________________________________________ Date _________________ A Different Malcolm X: From Nation of Islam Spokesman to Independent Political Activist From Malcolm X, “The Ballot or the Bullet,” April 3, 1964: http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1147 Mr. Moderator, Brother Lomax, brothers and sisters, friends and enemies: I just can’t believe everyone in here is a friend, and I don’t want to leave anybody out. The question tonight, as I understand it, is “The Negro Revolt, and Where Do We Go From Here?” or “What Next?” In my little humble way of understanding it, it points toward either the ballot or the bullet. Before we try and explain what is meant by the ballot or the bullet, I would like to clarify something concerning myself. I’m still a Muslim; my religion is still Islam. That’s my personal belief. Just as Adam Clayton Powell is a Christian minister who heads the Abyssinian Baptist Church in New York, but at the same time takes part in the political struggles to try and bring about rights to the black people in this country; and Dr. Martin Luther King is a Christian minister down in Atlanta, Georgia, who heads another organization fighting for the civil rights of black people in this country; and Reverend Galamison, I guess you’ve heard of him, is another Christian minister in New York who has been deeply involved in the school boycotts to eliminate segregated education; well, I myself am a minister, not a Christian minister, but a Muslim minister; and I believe in action on all fronts by whatever means necessary. -

Blksavage: a Study on the Elements of Traditional Radical Black Political Theories & Their Onc Tributions to Contemporary Black Political Thought" (2015)

The College of Wooster Libraries Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2015 ***Blksavage: A Study On The leE ments of Traditional Radical Black Political Theories & Their Contributions To Contemporary Black Political Thought Jestin B. Kusch The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Kusch, Jestin B., "***Blksavage: A Study On The Elements of Traditional Radical Black Political Theories & Their onC tributions To Contemporary Black Political Thought" (2015). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 6739. https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy/6739 This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The oC llege of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2015 Jestin B. Kusch “***BlkSavage” A STUDY ON THE ELEMENTS OF TRADITIONAL RADICAL BLACK POLITICAL THEORIES & THEIR CONTRIBUTIONS TO CONTEMPORARY BLACK POLITICAL THOUGHT By: Jestin B. Kusch An Independent Study Thesis Submitted to the Department of Political Science At the College of Wooster May, 2015 In partial fulfillment of the requirements of I.S. Thesis Advisor: Mark Weaver Second Reader: Eric Moskowitz 1 Table of Contents: Acknowledgments Foreword…………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Chapter ONE: “They Sleep, We Grind” ……………………………..………………………….