Behavioural and Metabolic Adaptations of Marine Isopods to the Rafting Life Style

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 17Th International Colloquium on Amphipoda

Biodiversity Journal, 2017, 8 (2): 391–394 MONOGRAPH The 17th International Colloquium on Amphipoda Sabrina Lo Brutto1,2,*, Eugenia Schimmenti1 & Davide Iaciofano1 1Dept. STEBICEF, Section of Animal Biology, via Archirafi 18, Palermo, University of Palermo, Italy 2Museum of Zoology “Doderlein”, SIMUA, via Archirafi 16, University of Palermo, Italy *Corresponding author, email: [email protected] th th ABSTRACT The 17 International Colloquium on Amphipoda (17 ICA) has been organized by the University of Palermo (Sicily, Italy), and took place in Trapani, 4-7 September 2017. All the contributions have been published in the present monograph and include a wide range of topics. KEY WORDS International Colloquium on Amphipoda; ICA; Amphipoda. Received 30.04.2017; accepted 31.05.2017; printed 30.06.2017 Proceedings of the 17th International Colloquium on Amphipoda (17th ICA), September 4th-7th 2017, Trapani (Italy) The first International Colloquium on Amphi- Poland, Turkey, Norway, Brazil and Canada within poda was held in Verona in 1969, as a simple meet- the Scientific Committee: ing of specialists interested in the Systematics of Sabrina Lo Brutto (Coordinator) - University of Gammarus and Niphargus. Palermo, Italy Now, after 48 years, the Colloquium reached the Elvira De Matthaeis - University La Sapienza, 17th edition, held at the “Polo Territoriale della Italy Provincia di Trapani”, a site of the University of Felicita Scapini - University of Firenze, Italy Palermo, in Italy; and for the second time in Sicily Alberto Ugolini - University of Firenze, Italy (Lo Brutto et al., 2013). Maria Beatrice Scipione - Stazione Zoologica The Organizing and Scientific Committees were Anton Dohrn, Italy composed by people from different countries. -

Colour Polymorphism and Genetic Variation in <Emphasis Type="Italic">Idotea Baltica</Emphasis> Populations

The Ecological Distribution of British Species of Idotea (Isopoda) STOR E. Naylor The Journal of Animal Ecology, Vol. 24, No. 2. (Nov., 1955), pp. 255-269. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0021-8790%28195511%2924%3A2%3C255%3ATEDOBS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-%23 The Journal of Animal Ecology is currently published by British Ecological Society. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/joumals/briteco.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is an independent not-for-profit organization dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of scholarly journals. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.j stor.org/ Tue Oct 3 15:24:28 2006 VOLUME 24, No. 2 NOVEMBER 1955 THE ECOLOGICAL DISTRIBUTION OF BRITISH SPECIES OF IDOTEA (ISOPODA) BY E. NAYLOR Marine Biological Station, Port Erin (With 4 Figures in the Text) INTRODUCTION Descriptions of the ecology of Idotea are often generalized, and there appears to be no comprehensive work on the habits of individual species. -

Belgian Register of Marine Species

BELGIAN REGISTER OF MARINE SPECIES September 2010 Belgian Register of Marine Species – September 2010 BELGIAN REGISTER OF MARINE SPECIES, COMPILED AND VALIDATED BY THE VLIZ BELGIAN MARINE SPECIES CONSORTIUM VLIZ SPECIAL PUBLICATION 46 SUGGESTED CITATION Leen Vandepitte, Wim Decock & Jan Mees (eds) (2010). Belgian Register of Marine Species, compiled and validated by the VLIZ Belgian Marine Species Consortium. VLIZ Special Publication, 46. Vlaams Instituut voor de Zee (VLIZ): Oostende, Belgium. 78 pp. ISBN 978‐90‐812900‐8‐1. CONTACT INFORMATION Flanders Marine Institute – VLIZ InnovOcean site Wandelaarkaai 7 8400 Oostende Belgium Phone: ++32‐(0)59‐34 21 30 Fax: ++32‐(0)59‐34 21 31 E‐mail: [email protected] or [email protected] ‐ 2 ‐ Belgian Register of Marine Species – September 2010 Content Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... ‐ 5 ‐ Used terminology and definitions ....................................................................................................... ‐ 7 ‐ Belgian Register of Marine Species in numbers .................................................................................. ‐ 9 ‐ Belgian Register of Marine Species ................................................................................................... ‐ 12 ‐ BACTERIA ............................................................................................................................................. ‐ 12 ‐ PROTOZOA ........................................................................................................................................... -

To Down Load Appendix 1

APPENDIX 1 Chapter 1 Pictures of dominant species ................................................................................................................................. 2 Species inventory of micro-invertebrate species found ....................................................................................... 16 Bathymetry Map of Pleasant Bay ........................................................................................................................ 18 Eelgrass Locations in Pleasant Bay ..................................................................................................................... 19 Sidescan Map of Pleasant Bay ............................................................................................................................. 20 Chapter 2 Species inventory of macro-invertebrate and fish species by gear type .............................................................. 21 Chapter 3 Prey otoliths and hard parts recovered during seal scat processing ..................................................................... 24 1 Pictures of dominant species Disclaimer: biological samples were treated with ethanol and Rose Bengal in the laboratory to preserve the samples. Rose Bengal is a stain commonly used in microscopy and stains cell tissue a bright pink. This is useful in the visual detection of microscopic animals in sediment samples. An overwhelming majority of micro invertebrate species do not have common names. The common names used here are listed in Pollock’s “A Practical Guide -

Crustacean Fauna of a Mussel Cultivated Raft System in the Black Sea

Arthropods, 2013, 2(2): 89-94 Article Crustacean fauna of a mussel cultivated raft system in the Black Sea Murat Sezgin, Eylem Aydemir Çil Sinop University Faculty of Fisheries Department of Marine Biology and Ecology TR57000 Sinop, Turkey E-mail: [email protected] Received 1 January 2013; Accepted 5 February 2013; Published online 1 June 2013 Abstract The aim of the current study was to make a faunistic analysis of the crustaceans associated with cultivated mussels grown on ropes. Mussel samples from 30 cm ropes were collected from rope-grown mussel beds by hand. The crustacean fauna associated with mussel population were quantified. The density of crustacean fauna associated with mussels was significantly greater within rope-grown mussel assemblages than on other biotopes around. Keywords Crustacea; Mytilus galloprovincialis; raft culture; rope-grown mussels; species richness. Arthropods ISSN 22244255 URL: http://www.iaees.org/publications/journals/arthropods/onlineversion.asp RSS: http://www.iaees.org/publications/journals/arthropods/rss.xml Email: [email protected] EditorinChief: WenJun Zhang Publisher: International Academy of Ecology and Environmental Sciences 1 Introduction A few species of Bivalvia in Black Sea live on hard substrate: the mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis fasten themselves with bissal threads to underwater stones, macroalgal stems or pier columns as nature habitats. The biodiversity associated with cultivated mussel assemblages depends partly on the source of the mussels and on the new habitat created by the method of cultivation. To date, no study has been made of the macrofauna associated with mussels in the habitats created by different methods of mussel cultivation in the Black Sea. -

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES an Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES An Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals By Paul Rudy, Jr. Lynn Hay Rudy Oregon Institute of Marine Biology University of Oregon Charleston, Oregon 97420 Contract No. 79-111 Project Officer Jay F. Watson U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 500 N.E. Multnomah Street Portland, Oregon 97232 Performed for National Coastal Ecosystems Team Office of Biological Services Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Department of Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 Table of Contents Introduction CNIDARIA Hydrozoa Aequorea aequorea ................................................................ 6 Obelia longissima .................................................................. 8 Polyorchis penicillatus 10 Tubularia crocea ................................................................. 12 Anthozoa Anthopleura artemisia ................................. 14 Anthopleura elegantissima .................................................. 16 Haliplanella luciae .................................................................. 18 Nematostella vectensis ......................................................... 20 Metridium senile .................................................................... 22 NEMERTEA Amphiporus imparispinosus ................................................ 24 Carinoma mutabilis ................................................................ 26 Cerebratulus californiensis .................................................. 28 Lineus ruber ......................................................................... -

Are Marine Isopods Picking Favorites with Colors? the Role of Color Sensing in Food Preference in Pentidotea Wosnesenskii

Are marine isopods picking favorites with colors? The role of color sensing in food preference in Pentidotea wosnesenskii Aurora Nelson1,2 Friday Harbor Labs FHL 470 A Research in Marine Biology Spring 2021 1 Friday Harbor Laboratories, University of Washington, Friday Harbor, WA 98250 2 Department of Marine Biology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195 Contact information: Aurora Nelson [email protected] Keywords: marine isopod, Pentidotea wosnesenskii, color sensing, chromatophores Nelson 1 Abstract The marine isopod Pentidotea wosnesenskii is one of many species that can change its color throughout its life. The variety of colors it can take on allows it to match the species of algae it lives on and consumes. While this isopod can change its color when moved to a new substrate, this requires it to build a new cuticle and molt, a process that takes weeks. It seems likely that it would be more efficient for an isopod to seek out algae that it is already matched to. This species is highly likely to have color sensing abilities as a way of adjusting their chromatophores, so they may use those abilities to search for a substrate that they can match. I placed isopods in containers where they had access to three different colors of algae. I hypothesized that adult isopods would show a preference for algae that was similar in color to their cuticles. However, the results of this study do not suggest that isopods use color sensing to move to matching backgrounds. Instead, they may be choosing substrates based on its quality as a food source or how well they can attach themselves to it. -

Hepatopancreatic Endosymbionts in Coastal Isopods (Crustacea: Isopoda)

Marine Biology 2001) 138: 955±963 Ó Springer-Verlag 2001 M. Zimmer á J. P. Danko á S. C. Pennings A. R. Danford á A. Ziegler á R. F. Uglow á T. H. Carefoot Hepatopancreatic endosymbionts in coastal isopods Crustacea: Isopoda), and their contribution to digestion Received: 28 August 2000 / Accepted: 8 December 2000 Abstract Three isopod species Crustacea: Isopoda), phenolic compounds was most developed in one of the commonly found in the intertidal and supratidal zones more marine species, suggesting that this trait may have of the North American Paci®c coast, were studied with evolved independently in isopod species that consume a respect to symbiotic microbiota in their midgut glands phenolic-rich diet, whether in marine habitats or on hepatopancreas). Ligia pallasii Oniscidea: Ligiidae) land. contained high numbers of microbialsymbionts in its hepatopancreatic caeca. Numbers of endosymbionts were strongly reduced by ingestion of antibiotics. By contrast, Introduction the hepatopancreas of Idotea wosnesenskii Valvifera: Idoteidae) and Gnorimosphaeroma oregonense Sphae- Endosymbionts are well known to play a key role in the romatidea: Sphaeromatidae) did not contain any mic- digestive processes of many terrestrialspecies summa- robiota. Results of feeding experiments suggest that rized in Martin 1983; Slaytor 1992; Breznak and Brune microbialendosymbionts contribute to digestive pro- 1994); however, their role in marine invertebrate species cesses in L. pallasii, the most terrestrialof the three is poorly understood. While studies have shown that gut isopods that we studied. The acquisition of digestion- microbiota exist in some marine invertebrates, know- enhancing endosymbionts may have been an important ledge of their nutritional role is scanty cf. -

Metapopulation Structure of the Marine Isopod Idotea Metallica, a Species Associated with Drifting Habitat Patches

Helgol Mar Res (2003) 56:259–264 DOI 10.1007/s10152-002-0126-y ORIGINAL ARTICLE L. Gutow · H.-D. Franke Metapopulation structure of the marine isopod Idotea metallica, a species associated with drifting habitat patches Received: 22 October 2001 / Revised: 25 July 2002 / Accepted: 28 August 2002 / Published online: 5 December 2002 © Springer-Verlag and AWI 2002 Abstract The neustonic isopod Idotea metallica inhab- Thus, the application of the metapopulation concept pos- its objects drifting at the sea surface. Animals found on es difficulties to benthic species with pelagic larvae be- floating patches represent not just ephemeral assemblag- cause discrete local populations are difficult to distin- es but persistent local populations. Drift material collect- guish. ed in the Mediterranean, the North Atlantic, and the In contrast, isopods, as peracarid crustaceans, develop North Sea harboured populations of up to about 50 ani- directly in the females’ brood pouch without planktonic mals including all developmental stages. In laboratory larval stages. Connectivity of discrete local populations experiments the species proved to be able to establish occurs only temporarily and depends on active migration populations on spatially limited, isolated substrates. The of the animals. Therefore isopods could be suitable tar- capacity of 5-litre-microcosms for I. metallica was about get organisms for marine metapopulation research. 130 animals. In the presence of the coastally distributed In addition to all kinds of benthic environments congener Idotea baltica, however, laboratory populations (Naylor 1972), isopods of the genus Idotea are also of I. metallica went extinct within 12 weeks. Even found associated with objects drifting at the sea surface though high colonisation rates can be expected in coastal (Franke et al. -

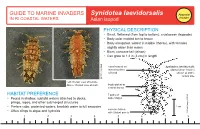

Synidotea Laevidorsalis Potential in RI COASTAL WATERS Asian Isopod Invader

GUIDE TO MARINE INVADERS Synidotea laevidorsalis Potential IN RI COASTAL WATERS Asian isopod Invader PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION • Small, flattened (from top to bottom), crustacean (Isopoda) • Body color mottled tan to brown • Body elongated, widest in middle (thorax), with females slightly wider than males • Blunt, concave tail (telson) • Can grow to 1.2 in (3 cm) in length eyes located on Synidotea laevidorsalis lateral surface (dorsal view, female) of head shown at 200% actual size SERTC / SCDNR SERTC Left: Dorsal view of female Above: Dorsal view of male body widest at central thorax HABITAT PREFERENCE 7 pairs of • Found in shallow, subtidal waters attached to docks, appendages pilings, ropes, and other submerged structures • Prefers calm, protected waters; brackish water to full seawater 1 cm concave telson • Often clings to algae and hydroids with 2 blunt points © Rob Gough, DFBW 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 GUIDE TO MARINE INVADERS Synidotea laevidorsalis Potential IN RI COASTAL WATERS Asian isopod Invader INVASION STATUS & ECOLOGICAL CONCERNS Synidotea laevidorsalis is native to the Western Pacific Ocean and has been introduced to Europe, South America, Australia, and the United States, including San Francisco Bay, South Carolina, and the Delaware Bayshore of New Jersey. A marine isopod, S. laevidorsalis must be submerged in water to breathe. S. laevidorsalis grows to about 3 cm in length and can be found on docks and pilings among seaweed and hydroids. This isopod is classified as an omnivorous scavenger, eating both dead and living material, particularly hydroids. The camouflage pattern on its body allows it to blend in with its environment, and the tiny claws on each leg help it cling to surfaces. -

Chapter 8 Benthic Assessment of Marine Areas of Particular

Chapter 8 Benthic assessment of marine areas of particular ecological importance within the German Baltic Sea EEZ Michael L. Zettlera and Fritz Gosselckb a Baltic Sea Research Institute, Rostock b Institute for Applied Ecology, Broderstorf Abstract The Habitats Directive is one of the main legal tools of the European Union to preserve biodiversity by maintaining and restoring natural habitats, and establishing a network of protected sites (NATURA 2000). One point of interest is the characterisation of marine habitats to localise the areas that fulfil the protection targets. Of the habitats listed in Annex I of the Habitats Directive, mainly reefs and sandbanks are relevant in the case of German Baltic offshore waters. Along a strong salinity gradient (5 to 25 psu), four planned offshore Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) within the German Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of the Baltic Sea were thoroughly investigated in this study. More than 250 locations were analysed using a combination of standard sampling methods, underwater video technique, and measurement of abiotic factors (salinity, oxygen, sediment parameters). The areas of interest were the Odra Bank (Oderbank), Adler Ground (Adlergrund), Kadet Trench (Kadetrinne), and Fehmarn Belt (Fehmarnbelt). The characteristic living communities (macrophytes, such as algae and sea grass, and macrozoobenthos such as worms, bivalves and crustaceans) for the different habitat types in these areas were characterised. Due to different salinity regimes, the benthic colonisation is different as well. In the Baltic Sea, with its decreasing salinity from west to east, the number of marine species declines, too. In the present study, altogether approximately 350 macrozoobenthic species and approximately 20 macrophytes were identified. -

Invertebrate ID Guide

11/13/13 1 This book is a compilation of identification resources for invertebrates found in stomach samples. By no means is it a complete list of all possible prey types. It is simply what has been found in past ChesMMAP and NEAMAP diet studies. A copy of this document is stored in both the ChesMMAP and NEAMAP lab network drives in a folder called ID Guides, along with other useful identification keys, articles, documents, and photos. If you want to see a larger version of any of the images in this document you can simply open the file and zoom in on the picture, or you can open the original file for the photo by navigating to the appropriate subfolder within the Fisheries Gut Lab folder. Other useful links for identification: Isopods http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-33/htm/doc.html http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-48/htm/doc.html Polychaetes http://web.vims.edu/bio/benthic/polychaete.html http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-34/htm/doc.html Cephalopods http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-44/htm/doc.html Amphipods http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-67/htm/doc.html Molluscs http://www.oceanica.cofc.edu/shellguide/ http://www.jaxshells.org/slife4.htm Bivalves http://www.jaxshells.org/atlanticb.htm Gastropods http://www.jaxshells.org/atlantic.htm Crustaceans http://www.jaxshells.org/slifex26.htm Echinoderms http://www.jaxshells.org/eich26.htm 2 PROTOZOA (FORAMINIFERA) ................................................................................................................................ 4 PORIFERA (SPONGES) ............................................................................................................................................... 4 CNIDARIA (JELLYFISHES, HYDROIDS, SEA ANEMONES) ............................................................................... 4 CTENOPHORA (COMB JELLIES)............................................................................................................................