Book Reviews the Last Great Necessity: Cemeteries in American

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil War Generals Buried in Spring Grove Cemetery by James Barnett

Spring Grove Cemetery, once characterized as blending "the elegance of a park with the pensive beauty of a burial-place," is the final resting- place of forty Cincinnatians who were generals during the Civil War. Forty For the Union: Civil War Generals Buried in Spring Grove Cemetery by James Barnett f the forty Civil War generals who are buried in Spring Grove Cemetery, twenty-three had advanced from no military experience whatsoever to attain the highest rank in the Union Army. This remarkable feat underscores the nature of the Northern army that suppressed the rebellion of the Confed- erate states during the years 1861 to 1865. Initially, it was a force of "inspired volunteers" rather than a standing army in the European tradition. Only seven of these forty leaders were graduates of West Point: Jacob Ammen, Joshua H. Bates, Sidney Burbank, Kenner Garrard, Joseph Hooker, Alexander McCook, and Godfrey Weitzel. Four of these seven —Burbank, Garrard, Mc- Cook, and Weitzel —were in the regular army at the outbreak of the war; the other three volunteered when the war started. Only four of the forty generals had ever been in combat before: William H. Lytle, August Moor, and Joseph Hooker served in the Mexican War, and William H. Baldwin fought under Giuseppe Garibaldi in the Italian civil war. This lack of professional soldiers did not come about by chance. When the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia in 1787, its delegates, who possessed a vast knowledge of European history, were determined not to create a legal basis for a standing army. The founding fathers believed that the stand- ing armies belonging to royalty were responsible for the endless bloody wars that plagued Europe. -

February Speaker

______________________________________________________________________________ CCWRT February, 2016 Issue Meeting Date: February 18, 2016 Place: The Drake Center (6:00) Sign-in and Social (6:30) Dinner (7:15) Business Meeting (7:30) Speaker Dinner Menu: Baked Stuffed Fish, Wild Rice, Ratatouille, Waldorf Salad, Rye Dinner Roll, and Carrot Cake Vegetarian Option: Upon request Speaker: Gene Schmiel, Washington D.C. Topic: Citizen-General: Jacob D. Cox ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ Reservations: If you do not have an Automatic Reservation, please remember to email your meeting reservation to [email protected] or call it in to Lester Burgin at 513-891-0610. If you are making a reservation for more than yourself, please provide the names of the others. Please note that all reservations must be in no later than 8:00 pm Tuesday, February 9, 2016. _______________________________________________________________________________________ February Speaker: In the 19th century there were few professional schools other than West Point, and so the self-made man was the standard for success. True to that mode, Jacob Dolson Cox, a long-time Cincinnati resident who is buried in Spring Grove Cemetery, fashioned himself into a Renaissance man. In each of his vocations and avocations— Civil War general, Governor of Ohio, Secretary of the Interior, President of the University of Cincinnati, Dean of the Cincinnati Law School, President of the Wabash Railroad, historian, and scientist— he was recognized as a leader. Cox’s greatest fame, however, is as the foremost participant-historian of the Civil War. His accounts of the conflict are to this day cited by serious scholars and serve as a foundation for the interpretation of many aspects of the war. -

Viewing an Exhibition

Winter 1983 Annual Report 1983 Annual Report 1983 Report of the President Much important material has been added to our library and the many patrons who come to use our collections have grown to the point where space has become John Diehl quite critical. However, collecting, preserving and dissemi- President nating Cincinnati-area history is the very reason for our existence and we're working hard to provide the space needed Nineteen Eight-three has been another banner to function adequately and efficiently. The Board of Trustees year for the Cincinnati Historical Society. The well docu- published a Statement of the Society's Facility Needs in December, mented staff reports on all aspects of our activities, on the to which you responded very helpfully with comments and pages that follow clearly indicate the progress we have made. ideas. I'd like to have been able to reply personally to each Our membership has shown a substantial increase over last of you who wrote, but rest assured that all of your comments year. In addition to the longer roster, there has been a are most welcome and carefully considered. Exciting things heartening up-grading of membership category across-the- are evolving in this area. We'll keep you posted as they board. Our frequent and varied activities throughout the develop. year attracted enthusiastic participation. Our newly designed The steady growth and good health of the quarterly, Queen City Heritage, has been very well received.Society rest on the firm foundation of a dedicated Board We are a much more visible, much more useful factor in of Trustees, a very competent staff and a wonderfully the life of the community. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly fi'om the original or copy submitted- Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from aity type of conçuter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to r i^ t in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9427761 Lest the rebels come to power: The life of W illiam Dennison, 1815—1882, early Ohio Republican Mulligan, Thomas Cecil, Ph.D. -

MOUNT AUBURN CEMETERY Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-8 OMB No. 1024-0018 MOUNT AUBURN CEMETERY Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Mount Auburn Cemetery Other Name/Site Number: n/a 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Roughly bounded by Mount Auburn Street, Not for publication:_ Coolidge Avenue, Grove Street, the Sand Banks Cemetery, and Cottage Street City/Town: Watertown and Cambridge Vicinityj_ State: Massachusetts Code: MA County: Middlesex Code: 017 Zip Code: 02472 and 02318 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): _ Public-Local: _ District: X Public-State: _ Site: Public-Federal: Structure: _ Object:_ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 4 4 buildings 1 ___ sites 4 structures 15 ___ objects 26 8 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 26 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: n/a NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 MOUNT AUBURN CEMETERY Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

GRAND ISLAND VETERANS HOME (GIVH) (Formerly NEBRASKA SOLDIER and SAILORS HOME) 1887-2005 215 Cubic Ft; 211 Boxes & 36 Volumes

1 RG97 Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) GRAND ISLAND VETERANS HOME (GIVH) (formerly NEBRASKA SOLDIER AND SAILORS HOME) 1887-2005 215 cubic ft; 211 boxes & 36 volumes History of Collection: The Grand Island Veterans Home, originally known as the Nebraska Soldiers and Sailors Home, opened in 1887 and was the first Veterans’ home in the state. A brief history of the facility is reproduced below from the DHHS website at: http://dhhs.ne.gov/Documents/GIVHHistory.pdf History of the Grand Island Veterans’ Home Nebraska’s oldest and largest home was established in 1887. The following is an excerpt taken from the Senate Journal of the Legislature of the State of Nebraska Twentieth Regular Session held in Lincoln on January 4, 1887: “WHEREAS, There are many old soldiers in Nebraska who, from wounds or disabilities received while in the union army during the rebellion, are in the county poorhouses of this state; therefore be it RESOLVED, That it is the sense of this Senate that a suitable building be erected and grounds provided for the care and comfort of the old soldiers of Nebraska in their declining years; RESOLVED, That a committee of five be appointed to confer with a committee of the House on indigent soldiers and marines to take such action as will look to the establishment of a State Soldiers’ Home.” Legislative Bill 247 was passed on March 4, 1887 for the establishment of a soldiers’ home and the bill stipulated that not less than 640 acres be donated for the site. The Grand Island Board of Trade had a committee meeting with the citizens of Grand Island to secure funds to purchase land for the site of the home. -

Ohio UGRR.Pdf

HAMILTON AVENUE – ROAD TO FREEDOM 13. Jonathan Cable – A Presbyterian minister, his family fugitive slaves in a tool house and wooden shed attached to once lived north of 6011 Belmont Avenue. Levi Coffin his house. 1. Hall of Free Discussion site - The Hall was so named by wrote about the deeds of Cable, who procured clothing and 26. Mt. Healthy Christian Church – 7717 Harrison Avenue James Ludlow, son of Israel Ludlow (a Hamilton County gave slaves shelter in his house. He is seen in this – Founded by Pastor David S. Burnet, part of the Cincinnati abolitionist surveyor whose first home was built in photograph as the tall man in the back row. The man with Burnet family, this church was torn apart by the slavery Northside) who built it for the purpose of open discussion the top hat is Levi Coffin; they are with some of those they question. It expelled Aaron Lane for his abolitionist views of controversial topics. After the Lane Debates, some helped to escape. against the protests of other members and for six years the abolitionist seminary students taught classes here to blacks, 14. Samuel and Sally Wilson house – 1502 Aster Place – church stopped holding services. while others taught here and then moved on to Oberlin A staunch abolitionist family, the Wilsons moved to 27. Rev. Dr. John Witherspoon Scott – 7601 Hamilton College. Abolitionist speakers such as Rev. Lyman Beecher College Hill in 1849, purchasing land and a small log cabin Avenue – Built in 1840, this was a station for the and William Cary were popular. -

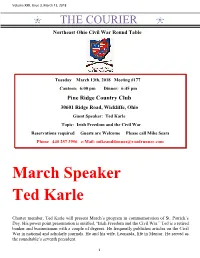

March Speaker Ted Karle

Volume XXII, Issue 3, March 13, 2018 THE COURIER Northeast Ohio Civil War Round Table Tuesday March 13th, 2018 Meeting #177 Canteen: 6:00 pm Dinner: 6:45 pm Pine Ridge Country Club 30601 Ridge Road, Wickliffe, Ohio Guest Speaker: Ted Karle Topic: Irish Freedom and the Civil War Reservations required Guests are Welcome Please call Mike Sears Phone 440 257 3956 e-Mail: [email protected] March Speaker Ted Karle Charter member, Ted Karle will present March’s program in commemoration of St. Patrick’s Day. His power point presentation is entitled, “Irish Freedom and the Civil War.” Ted is a retired banker and businessman with a couple of degrees. He frequently publishes articles on the Civil War in national and scholarly journals. He and his wife, Leonarda, life in Mentor. He served as the roundtable’s seventh president. 1 Volume XXII, Issue 3, March 13, 2018 A Stroll Through Spring Grove Cemetery By Paul Siedel Among the many Civil War sites here in Ohio is Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati. Besides being a fantastic arboretum, featuring many native and exotic species of plants it is the final resting place for many well known Civil War personalities. Upon entering the Cemetery one is taken by the remarkable gatehouse. Built in the 1880s it is truly a remarkable piece of late Victorian architecture. In the office one may obtain maps to the graves of many of the people that made Ohio one of our premier states both in business, industry and opportunity. Names such as Kroger, Chase, Hooker, Jacob Cox and others. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

The International Battleaxe 2010 V.2

Clan Maclean International Association COUNCIL as at APRIL 2010 Chief Sir Lachlan Maclean of Duart and Morvern, Bt., CVO, DL Duart Castle, Isle of Mull, Argyl PA64 6AP Chieftains Robin Maclean of Ardgour, Salachan House, Ardgour, Fort William PH33 7AB The Very Rev. Allan Maclean of Dochgarroch, 5 North Charlotte St, Edinburgh EH2 4HR Sir Charles Maclean of Dunconnel Bt., Strachur House, Strachur, Argyll PA27 8BX Nicolas Maclean of Pennycross CMG, 30 Malwood Road, London SW12 8EN Richard Compton Maclean of Torloisk, Torloisk House, Isle of Mull, Argyll PA74 6NH President Ian MacLean, 72 Tidnish Cove Lane, RR #2, Amherst, Nova Scotia, B4H 3X9, Canada Vice President Peter MacLean, 59A Alness Street, Applecross, Western Australia 6153 Honorary Vice Presidents Donald H MacLean, 134 Whitelands Avenue, Chorleywood, Herts WD3 5RG Lt. Col. Donald MacLean, Maimhor, 2 Fullerton Drive, Seamill, Ayrshire KA23 9HT Scotland Presidents of Clan Maclean Associations Clan Maclean Association The Very Rev. Allan Maclean of Dochgarroch, 5 North Charlotte St, Edinburgh EH2 4HR Clan Maclean Association of London Nicolas Maclean of Pennycross CMG, 30 Malwood Road, London SW12 8EN Clan Gillean USA Robert S McLean, 1333 Pine Trail, Clayton, North Carolina, 27520-9345, USA Clan Maclean Association of California & Nevada Jeff MacLean, CMA California, PO Box 2191, Santa Rosa, CA 95405, USA Clan Maclean Association, Pacific NW, USA Jim McClean, 9275 SW Cutter Pl, Beaverton, OR 97008–7706, USA Clan Maclean Association, Atlantic (Canada) Murray MacLean, 2337 Route 106, -

Noah Haynes Swayne

Noah Haynes Swayne Noah Haynes Swayne (December 7, 1804 – June 8, 1884) was an Noah Haynes Swayne American jurist and politician. He was the first Republican appointed as a justice to the United States Supreme Court. Contents Birth and early life Supreme Court service Retirement, death and legacy See also Notes References Further reading Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States In office Birth and early life January 24, 1862 – January 24, 1881 Nominated by Abraham Lincoln Swayne was born in Frederick County, Virginia in the uppermost reaches of the Shenandoah Valley, approximately 100 miles (160 km) Preceded by John McLean northwest of Washington D.C. He was the youngest of nine children of Succeeded by Stanley Matthews [1] Joshua Swayne and Rebecca (Smith) Swayne. He was a descendant Personal details of Francis Swayne, who emigrated from England in 1710 and settled Born December 7, 1804 near Philadelphia.[2] After his father died in 1809, Noah was educated Frederick County, Virginia, U.S. locally until enrolling in Jacob Mendendhall's Academy in Waterford, Died June 8, 1884 (aged 79) Virginia, a respected Quaker school 1817-18. He began to study New York City, New York, U.S. medicine in Alexandria, Virginia, but abandoned this pursuit after his teacher Dr. George Thornton died in 1819. Despite his family having Political party Democratic (Before 1856) no money to support his continued education, he read law under John Republican (1856–1890) Scott and Francis Brooks in Warrenton, Virginia, and was admitted to Spouse(s) Sarah Swayne the Virginia Bar in 1823.[3] A devout Quaker (and to date the only Quaker to serve on the Supreme Court), Swayne was deeply opposed to slavery, and in 1824 he left Virginia for the free state of Ohio. -

Cincinnati Underwater Index.Fm

Cincinnati Under Water The 1937 Flood by Steven J. Rolfes Index A Armleder, Otto 177 A&P Grocers 125, 134 Armstrong, Leon 48 Abbe Observatory 40, 96, 173 Army Corps of Engineers 37, 59, 223, Abbe, Cleveland 96 225 Addyston 4, 85, 103, 130, 142, 189, 201, Art Deco 34, 58, 101, 102, 138, 212 203 Associated Charities 23, 27, 111 Aequi 135 Associated Press 108 Aeronautical Corporation 95 Atkins, Rev. Henry Pearce 205 Alexander, Edward F. 48, 135 Atlas Rubber Products Co. 87 Allenwood, Pa. 195 Ault Park 138 Alms Hotel 106, 208, 209, 211, 212 Aurora bridge 32 Alms Park 138 automobiles 32, 45, 52, 78, 97, 103, 105, American Airlines 53 129, 142, 168, 185, 186, 188, American Civil War 18, 20, 128, 137 196 American Legion 53, 65, 168, 194, 218, Avondale 28, 197 224 American Products Co. 166 B Ames, John H. 48, 98, 141 B&O Railroad roundhouse 82, 158 Amrein, John 179 Bailey, Miriam 217 Anderson Township 72 Baldwin, Mollie 25 Anderson, Richard Cligh 72 ban on theaters 141 Angel, George 70 Banker, Charley 16 Anna Louise Inn 106 Barenscheer, Leo 157 Anstead, Harry 87 Barlace, William 127 Ante, Louis 199 baseball park 20 Archdiocese of Cincinnati 176 Batavia, Ohio 93 Armleder Building 177 battle of Mons Algidus 135 232 Cincinnati Under Water: The 1937 Flood Bauer, Nicholas 194 Bush, Sheldon 153 Baumberger, George 48 Butler, Smedley 213 Baumer, John 166 Beckman, Clem 83 C Beechmont 95 C&O bridge 202 Bell, Samuel W. 140 C&O Railroad 122, 123, 149 Bellevue, Ky.