Celebrating the Scholarship of Polly Schaafsma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A16 TV Friday [16-16].Indd

16 TIMES-TRIBUNE / FRIDAY, MARCH 9, 2012 ENTERTAINMENT , FRIDAY PRIME TIME MARCH 9, 2012 PEOPLE IN THE NEWS 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 BROADCAST ABC & WATE 6 ABC World News & Judge Judy & Judge Shark Tank Body jewelry; organic Primetime: What Would You Do? 20/20 (N) ’ Å & WATE 6 (:35) Nightline News at 6 With Diane Saw- D Entertain- Judy Å skin care. (N) ’ Å (N) ’ Å News at 11 (N) Å WATE & D ABC 36 yer (N) Å ment Tonight D The Insider D ABC 36 WTVQ D News at 6 (N) Å News at 11 Ky. company sues CBS Y News CBS Evening Y Season College Basketball SEC Tournament, Third Quarterfinal: Teams TBA. From New Orleans. (N) College Basketball SEC Tournament, Fourth Quarterfinal: Teams TBA. From ( Local 8 News News With Scott Special (Live) New Orleans. (N) (Live) WYMT Y ; Newsfirst at Pelley (N) ’ Å ( Entertain- WVLT ( 6:00pm ment Tonight WKYT ; ; Wheel of to stop name airing Fortune NBC 2 LEX 18 News NBC Nightly 2 LEX 18 2 Access Hol- Who Do You Think You Are? “Je- Grimm “Plumed Serpent” Investigat- Dateline NBC (N) ’ Å 2 LEX 18 News (:35) The Tonight at 6 (N) Å News (N) ’ Å NEWS lywood rome Bettis” Retired football player ing an arson-related homicide. (N) at 11 Show With Jay WLEX 2 * News (N) * Wheel of * Jeopardy! Jerome Bettis. (N) ’ Å ’ Å * 10 News Leno Å WBIR * Fortune Nightbeat on Limbaugh FOX Judge Judy ’ Å Judge Judy ’ Å Two and a Half The Big Bang Kitchen Nightmares “Blackberry’s; Leone’s” Improving a New Jersey eatery. -

APÉNDICE BIBLIOGRÁFICO1 I. Herederas De Simone De Beauvoir A. Michèle Le Doeuff -Fuentes Primarias Le Sexe Du Savoir, Aubier

APÉNDICE BIBLIOGRÁFICO1 I. Herederas de Simone de Beauvoir A. Michèle Le Doeuff -Fuentes primarias Le sexe du savoir, Aubier, Paris : Aubier, 1998, reedición: Champs Flammarion, Paris, 2000. Traducción inglesa: The Sex of Knowing. Routledge, New-York, 2003. L'Étude et le rouet. Des femmes, de la philosophie, etc. Seueil, Paris, 1989. Tradcción inglesa: Hipparchia's Choice, an essay concerning women, philosophy, etc. Blackwell, Oxford, 1991. Traducción española: El Estudio y la rueca, ed. Catedra, Madrid, 1993. L'Imaginaire Philosophique, Payot, Lausanne, 1980. Traducción inglesa: The Philosophical Imaginary, Athlone, London, 1989. The Philosophical Imaginary ha sido reeditado por Continuum, U. K., 2002. "Women and Philosophy", en Radical Philosophy, Oxford 1977; original francés en Le Doctrinal de Sapience, 1977; texto inglés vuelto a publicar en French Feminist Thought, editado por Toril Moi, Blackwell, Oxford 1987. Ver también L'Imaginaire Philosophique o The Philosophical Imaginary, en una antología dirigida por Mary Evans, Routledge, Londres. "Irons-nous jouer dans l'île?", en Écrit pour Vl. Jankélévitch, Flammarion, Flammarion, 1978. "A woman divided", Ithaca, Cornell Review, 1978. "En torno a la moral de Descartes", en Conocer Descartes 1 Este apéndice bibliográfico incluye las obras de las herederas de Simone de Beauvoir, así como las de Hannah Arendt y Simone Weil, y algunas de las fuentes secundarias más importantes de dichas autoras. Se ha realizado a través de una serie de búsquedas en la Red, por lo que los datos bibliográficos se recogen tal y como, y en el mismo orden con el que se presentan en las diferente páginas visitadas. y su obra, bajo la dirección de Victor Gomez-Pin, Barcelona 1979. -

El Llegat Dels Germans Grimm En El Segle Xxi: Del Paper a La Pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira I Virgili [email protected]

El llegat dels germans Grimm en el segle xxi: del paper a la pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira i Virgili [email protected] Resum Les rondalles que els germans Grimm van recollir als Kinder- und Hausmärchen han traspassat la frontera del paper amb nombroses adaptacions literàries, cinema- togràfiques o televisives. La pel·lícula The brothers Grimm (2005), de Terry Gilli- am, i la primera temporada de la sèrie Grimm (2011-2012), de la cadena NBC, són dos mostres recents d’obres audiovisuals que han agafat les rondalles dels Grimm com a base per elaborar la seva ficció. En aquest article s’analitza el tractament de les rondalles que apareixen en totes dues obres (tenint en compte un precedent de 1962, The wonderful world of the Brothers Grimm), així com el rol que adopten els mateixos germans Grimm, que passen de creadors a convertir-se ells mateixos en personatges de ficció. Es recorre, d’aquesta manera, el camí invers al que han realitzat els responsables d’aquestes adaptacions: de la pantalla (gran o petita) es torna al paper, mostrant quines són les rondalles dels Grimm que s’han adaptat i de quina manera s’ha dut a terme aquesta adaptació. Paraules clau Grimm, Kinder- und Hausmärchen, The brothers Grimm, Terry Gilliam, rondalla Summary The tales that the Grimm brothers collected in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen have gone beyond the confines of paper with numerous literary, cinematographic and TV adaptations. The film The Brothers Grimm (2005), by Terry Gilliam, and the first season of the series Grimm (2011–2012), produced by the NBC network, are two recent examples of audiovisual productions that have taken the Grimm brothers’ tales as a base on which to create their fiction. -

Land~~Ing'betweentwo ''''Orlds ,'One Dead, ;'.1.[; V" :,: The"Other"Po\'Terless to Be Born

·.... !tIn the Shadgw of the Golden Bough": " ' , "'" in resHonse to Lienhardt , 'Chaosis' new, "And has no pastel" future ~, Praise the fevl :vlho bUilt in chaos our bastion and our home. • Such is Edliin' tfu:i~' s response to the dilemma which faced liJ8.nyEnglish wri ters at the turn of the century - the feeling that, unity; of culture had been lost in the mechanistica,nd scientific.yorld, that the, increase in knO';11edse of ,other societies led to a breakdown of confidence in one's own. Li'enhal~dtih:d:gshi:"wn'(1973;' p'. '61) how'the Hritings' of ahthropologists at this time contributed. ,to many crea:~ive writers' sense of ali~@tio:n, almost" of' anomilit~!:,L"i: "" "" ,,';' ,,:, ' . \'land~~ing'betweentwo ''''orlds ,'one dead, ;'.1.[; v" :,: The"other"po\'Terless to be born. "', '~;.-'!~,' ~: ~ ~ r\~.L 'i~',~-:~'tV""-'" "v,.~ , ~ ; ;:·t'.!'.:·.i. i ':",t":i:;;" ... ''' ••• , Anthropologioa.l w'rit ings provided a new frame\'l'Ork :i:'or experience. a. mode of understanding which atteurpted to s~ the iweld through the Slyes of ,savages' and 'primitives' and in doing so recognised that the savage might exclude t:16 :2uropean from his world viow as much as the ~iuropean had been accustomed to exclude the savage. The sense of disintegration that 'this gave rise to is traced in various directions by Lienhardt. This new relativism created an excess of lmowledge \'lhich Nietzsche as early as 1909 called 'dangerous' and 'harmful'. It also gave rise to an excess of consciousness - of intellectual awareness. D. H. LaN'rence in particular represented this as destructive of finer sensi ti vi ties, of spontaneity and emotional response. -

![San Diego Public Library New Additions May 2009 [April 1, 2009 – May 14, 2009]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2271/san-diego-public-library-new-additions-may-2009-april-1-2009-may-14-2009-2382271.webp)

San Diego Public Library New Additions May 2009 [April 1, 2009 – May 14, 2009]

San Diego Public Library New Additions May 2009 [April 1, 2009 – May 14, 2009] Adult Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities California Room 100 - Philosophy & Psychology CD-ROMs 200 - Religion Compact Discs 300 - Social Sciences DVD Videos/Videocassettes 400 - Language eAudiobooks, eBooks & eVideos 500 - Science Fiction 600 - Technology Foreign Languages 700 - Art Genealogy Room 800 - Literature Graphic Novels 900 - Geography & History Large Print Audiocassettes Newspaper Room Audiovisual Materials Biographies Fiction Call # Author Title FIC/AALBORG Aalborg, Gordon. The horse tamer's challenge : a romance of the old west FIC/ADAMS Adams, Will, 1963- The Alexander cipher FIC/ADDIEGO Addiego, John. The islands of divine music FIC/ADLER Adler, H. G. The journey : a novel FIC/AGEE Agee, James, 1909-1955. A death in the family FIC/AIDAN Aidan, Pamela. Duty and desire : a novel of Fitzwilliam Darcy, gentleman FIC/AIDAN Aidan, Pamela. These three remain : a novel of Fitzwilliam Darcy, gentleman FIC/AKPAN Akpan, Uwem. Say you're one of them [MYST] FIC/ALBERT Albert, Susan Wittig. The tale of Briar Bank : the cottage tales of Beatrix Potter [MYST] FIC/ALBERT Albert, Susan Wittig. Wormwood FIC/ALBOM Albom, Mitch, 1958- The five people you meet in heaven FIC/ALLEN Allen, Jeffery Renard, 1962- Holding pattern : stories [SCI-FI] FIC/ALLSTON Allston, Aaron. Star wars : legacy of the force : betrayal FIC/AMBLER Ambler, Eric, 1909-1998. A coffin for Dimitrios FIC/AMIS Amis, Kingsley. Lucky Jim FIC/ANAYA Anaya, Rudolfo A. Bless me, Ultima FIC/ANAYA Anaya, Rudolfo A. The man who could fly and other stories [SCI-FI] FIC/ANDERSON Anderson, Kevin J., 1962- The ashes of worlds FIC/ANDERSON Anderson, Sherwood, 1876-1941. -

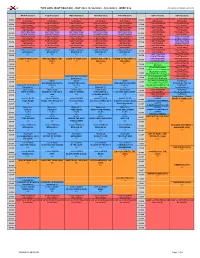

MAY 2021 (4/26/2021 - 5/2/2021) - WEEK #18 Date Updated:4/16/2021 2:24:45 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - MAY 2021 (4/26/2021 - 5/2/2021) - WEEK #18 Date Updated:4/16/2021 2:24:45 PM MON (4/26/2021) TUE (4/27/2021) WED (4/28/2021) THU (4/29/2021) FRI (4/30/2021) SAT (5/1/2021) SUN (5/2/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 The Laws of Fantasy Remix Matthew J. Dauphin Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE LAWS OF FANTASY REMIX By MATTHEW J. DAUPHIN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2017 Matthew J. Dauphin defended this dissertation on March 29, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: Barry Faulk Professor Directing Dissertation Donna Marie Nudd University Representative Trinyan Mariano Committee Member Christina Parker-Flynn Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To every teacher along my path who believed in me, encouraged me to reach for more, and withheld judgment when I failed, so I would not fear to try again. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ v 1. AN INTRODUCTION TO FANTASY REMIX ...................................................................... 1 Fantasy Remix as a Technique of Resistance, Subversion, and Conformity ......................... 9 Morality, Justice, and the Symbols of Law: Abstract -

ENG 402: Advanced Placement English Literature & Composition Summer Reading

ENG 402: Advanced Placement English Literature & Composition Summer Reading Dear students, Welcome to Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition! You have chosen a challenging, but rewarding path. This course is for students with intellectual curiosity, a strong work ethic, and a desire to learn. I know all of you have been well prepared for the “Wonderful World of Literature” in which we will delve into a wide selection of fiction, drama, and poetry. In order to prepare for the course, you will complete a Summer Reading Assignment prior to returning to school in the fall. Your summer assignment has been designed with the following goals in mind: to help you build confidence and competence as readers of complex texts; to give you, when you enter class in the fall, an immediate basis for discussion of literature – elements like narrative viewpoint, symbolism, plot structure, point of view, etc.; to set up a basis for comparison with other works we will read this year; to provide you with the beginnings of a repertoire of works you can write about on the AP Literature Exam next spring; and last but not least, to enrich your mind and stimulate your imagination. If you have any questions about the summer reading assignment (or anything else pertaining to next year), please feel free to email me ([email protected]). I hope you will enjoy and learn from your summer reading. I am looking forward to seeing you in class next year! Have a lovely summer! Mrs. Yee Read: How to Read Literature Like a Professor by Thomas C. -

The Ecological Imagination of John Cowper Powys: Writing, 'Nature', and the Non-Human

The Ecological Imagination of John Cowper Powys: Writing, 'Nature', and the Non-human Michael Stephen Wood Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of English September 2017 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his/her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2017 The University of Leeds and Michael Stephen Wood The right of to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 Acknowledgements Thanks are due, first and foremost, to Dr. Fiona Becket for her unswerving belief and encouragement. This thesis would not have been possible without the support of Stuart Wood, Susan Bayliss, Elaine Wood, Paul Shevlin, and Jessica Foley, all of whom have my love and gratitude. Further thanks are due to Dr. Emma Trott, Dr. Frances Hemsley, Dr. Ragini Mohite, Dr. Hannah Copley, and Dr. Georgina Binnie for their friendship and support, and to Kathy and David Foley for their patience in the final weeks of this project. Thanks to Adrienne Sharpe of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library for facilitating access to Powys’s correspondence with Dorothy Richardson. I am indebted to everyone in the Leeds School of English who has ever shared a conversation with me about my work, and to those, too numerous to mention, whose teaching has helped to shape my work and thinking along the way. -

When It Comes to Wine,Get the Lead Out

B12 THE NEWS-ENTERPRISE CLASSIFIEDS THURSDAY, APRIL 26, 2012 CROSSWORD When it comes to wine,get the lead out Dear Heloise: In a recent HINTS do. Start by washing the proximately 260 applica- letter, a reader inquired FROM wood spoons in soap and tions — that equals about about removing wine hot water, then let them dry. HELOISE three months’ worth (if you residue from a lead-crystal Next, wipe each with miner- apply lipstick three times a decanter. Please do your al oil (not olive or vegetable day). readers a service and warn should be used with caution, oil, because it can become Lipstick has a shelf life of them about a medical direc- especially with children and rancid). one to two years. However, tive stating wine should nev- women of childbearing age Let the spoons sit for a if it looks, smells or tastes er be stored in lead crystal, — they should use lead-free couple of hours or over- funny, that is an indication as lead can and will leach night. Next, wipe off the ex- crystal, if possible. None of that the lipstick needs to be into the wine. In addition, cess, and they are ready to this information is on the disposed of. pregnant women are ad- use. FDA website. However, it is PET-FOOD BAG. Dear vised against drinking any- available when you call the It’s always a good idea to Heloise: I buy the large thing from lead crystal. — FDA (888-463-6332). hand-wash wooden items. Barbara C., Scotch Plains, P.S.: Many people call all Placing them in the dish- bags of dog and cat food. -

The Fairy Tale and Its Uses in Contemporary New Media and Popular Culture

humanities The Fairy Tale and Its Uses in Contemporary New Media and Popular Culture Edited by Claudia Schwabe Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Humanities www.mdpi.com/journal/humanities Claudia Schwabe (Ed.) The Fairy Tale and Its Uses in Contemporary New Media and Popular Culture This book is a reprint of the Special Issue that appeared in the online, open access journal, Humanities (ISSN 2076-0787) in 2016, available at: http://www.mdpi.com/journal/humanities/special_issues/fairy_tales Guest Editor Claudia Schwabe Assistant Professor, Department of Languages, Utah State University, USA Editorial Office MDPI AG St. Alban-Anlage 66 Basel, Switzerland Publisher Shu-Kun Lin Assistant Editor Jie Gu 1. Edition 2016 MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade ISBN 978-3-03842-300-3 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-03842-301-0 (electronic) Articles in this volume are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY), which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles even for commercial purposes, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book taken as a whole is © 2016 MDPI, Basel, Switzerland, distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC BY-NC-ND) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Table of Contents List of Contributors ......................................................................................................... VII Claudia Schwabe The Fairy Tale and Its Uses in Contemporary New Media and Popular Culture Introduction Reprinted from: Humanities 2016, 5(4), 81 http://www.mdpi.com/2076-0787/5/4/81 ......................................................................... -

Entheogens, the Conscious Brain and Existential Reality Chris King Complementary Video: Entheogens, Culture and the Conscious Brain

Entheogens, the Conscious Brain and Existential Reality Chris King Complementary video: Entheogens, Culture and the Conscious Brain http://youtu.be/pY2MDqdv-No Abstract: The purpose of this article is to provide a ‘state of the art’ research overview of what is currently known about how entheogens, including the classic psychedelics, affect the brain and transform conscious experience through their altered receptor dynamics, and to explore their implications for understanding the conscious brain and its relationship to existential reality, and their potential utility in our cultural maturation and understanding of the place of sentient life in the universe. Contents 1. Cultural and Historical Introduction 2. The Enigma of Subjective Consciousness 3. Fathoming the Mind-Brain Relationship and Experiential Modalities 4. Doors of Perception: Classic Psychedelics and Serotonin Receptor Agonists 5. Doors of Dissociation: Ketamine and the NMDA Receptor Antagonists 6. Salvinorin-A and κ-Opioid Dissociatives 7. Cannabinoids 8. Entactogens 9. Doors of Delirium: Scopolamine and Muscarinic Acetyl-choline Antagonists 10. Safety Considerations of Psychedelic Use and Global Drug Policy 11. An Across-the-Spectrum Case Study 12. Why the Neurotransmitters: Cosmology and Evolution 13. Conclusion 14. References 1: Cultural and Historical Introduction Human societies have been actively using psychoactive substances since the earliest cultures emerged. In “The Alchemy of Culture” Richard Rudgley notes that European cave depictions, from the paleolithic on, abound with both herbivorous animals of the hunt and geometrical entopic patterns similar to the phosphenes seen under sensory withdrawal and under the effects of psychotropic herbs. By the time we find highly-decorated pottery ‘vase supports’ in Middle Neolithic France, we have evidence consistent with their ritual use as opium braziers.