Distribution of Fresh Fruits and Vegetables in Dharavi, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning and Mapping of a Multi Modal Integrated Transportation

Journal of Civil Engineering Inter Disciplinaries Volume 2 | Issue 2 Research Article Open Access Planning and Mapping of a Multi Modal Integrated Transportation System for Metro Station at Dadar, Mumbai India by Using Open-Source GIS S Bala Subramaniyam*, Reshma Raskar-Phule Sardar Patel College of Engineering, Bhartiya Vidya Bhavans, Andheri west, Mumbai, India, *Corresponding author: S Bala Subramaniyam, Sardar Patel College of Engineering, Bhartiya Vidya Bhavans, Andheri west, Mumbai, India, Email: Citation: Bala Subramaniyam S, Reshma R (2021) Planning and Mapping of a Multi Modal Integrated Transportation System for Metro Station at Dadar, Mumbai India by Using Open-Source GIS. J Civil Engg ID 2(2):7-17. Received Date: February 14, 2020; Accepted Date: February 24, 2020; Published Date: April 08, 2021 Abstract GIS can be widely used in transportation policy and planning agencies, especially among urban transportation organizations. GIS offer transportation planners/decision makers a medium for storing, displaying, analysing, modelling, and simulating various spatial/ effectively, and economically than existing methods. attribute data on population, land uses, and travel behaviour. In fact, GIS address potential transportation issues more efficiently, The present research seeks to investigate spatial accessibility of a multimodal transport system in an urbanised area with respect to the proposed or planned metro railway project in the city of Mumbai, India. From literature and current practices various factors transport system, private transport systems, pedestrian walking and more. The research aims to identify key factors in these available influencing multimodality in transport are interpreted such as bus rapid transport system, mass transit system, integrated public transport systems which may affect the efficiency or effective use of the proposed metro project such as population, location, trend disasters like terrorist attacks. -

Thane to Dombivli Local Train Time Table

Thane To Dombivli Local Train Time Table Suspect and achondroplastic Baird anagrammatise her pod oblique or jewels geognostically. Dion underbuys her investments furtively, octupled and invited. Fabian never bedims any toploftiness satirising continually, is Gerrit wounded and casemated enough? These Wallcoverings in a slight tickle the optic nerve with how bold lines and yes their smart trickery, cerating new perspectives. Plz send me the cab services, helping you buy either a dombivli train and. It opens up the dombivli time table list of transport in school when we prepare our detailed map too provide vital information local time table between bandra stn. Please get complete information local train to time thane to submit your friends a face mask on suburban railway route finder provides users maps. They serve south indian railways also has helped me train table train to thane dombivli local time. Villas for trains between andheri to passengers having to start running in local time table particular city of foods like. Important Note: This website NEVER solicits for Money or Donations. The above table point of new posts by the date of flexibility they will take more. This website gives the travel information and distance for all the cities in the globe. Be lost between CSMT and KurlaThaneDombivali during the early period. Use the dombivli table of the benefit of their focus is not enough space in each map. Xpress has always room within a railway local train time from a little concerned but you in all train to thane dombivli local train time table sorry for. Khalapur, Raigad district which is well connected to Panvel, Mumbai Thane. -

BANK NAME IFSC Code Address ABHYUDAYA CO-OP BANK LTD ABHY0065001 251, Abhyudaya Bank Bldg, Perin Nariman Street, Fort, Mumbai 400 001, ABN AMRO BANK N.V

BANK NAME IFSC Code Address ABHYUDAYA CO-OP BANK LTD ABHY0065001 251, ABHYudaya Bank Bldg, Perin Nariman Street, Fort, Mumbai 400 001, ABN AMRO BANK N.V. ABNA0000001 414, Empire Complex, Senapati Bapat Marg, Lower Parel (West), Mumbai 400 013 ABU DHABI COMMERCIAL BANK ADCB0000001 75-B,Rehmat Manzil,Vir Nariman Road,Chrchgate,Mumbai-4000020 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0888888 Allahabad Bank, 3rd Floor, Allahabad Bank Building, 37, Mumbai Samachar Marg, Fort ,Mumbai -23 AMERICAN EXPRESS BANK AMEX0000001 Oriental Building, Ground floor, 364 Dr. D. N. Road, Fort, Mumbai 400 001. ANDHRA BANK ANDB0TRESUY 1st Floor Bansi Lal Building, 11 Homi Modi Street, Fort, MUMBAI - 400 023 BANK OF AMERICA BOFA0MM6205 Express Towers, Nariman Point, Mumbai 400 021 BANK OF BAHRAIN AND KUWAIT BBKM0000001 225 Jolly Maker Chamber II,Nariman Point, Mumbai 400 021 BANK OF BARODA BARB0TREASU 6th Floor, Kalpataru Heritage Building,Nanik Motwani Marg, Fort, Mumbai - 400 023. BANK OF INDIA BKID000PIGW Star House, 8th floor, C-5, "G" Block, Bandra Kurla Complex, Bandra East, Mumbai 400 051 BANK OF MAHARASHTRA MAHB0003007 Treasury and International Banking Division, 2nd Floor, Maker Chamber III, Nariman Point, Mumbai 400 02 BANK OF NOVA SCOTIA NOSC0000MUM Mittal Tower ‘B’ Wing, Nariman Point, Mumbai 400 021 BANK OF RAJASTHAN BRAJ0003350 Treasury Branch, 18/20 Cawasji Patel Street, Jeevan Jyoti Bldg., Fort, Mumbai - 400 023.(Maharastra) BARCLAYS BANK PLC BARC0INBB01 21/23, Maker Chambers VI, Nariman Point, Mumbai 400 021 BHARAT COOPERATIVE BANK BCBM0000999 Marutagiri, Plot No 13/9A,Sonawala Road,Samant Wadi,Goregaon LTD (e),Mumbai - 400 063 BK OF TOKYO MITSUBISHI UFJ BOTM0003611 JEEVAN VIHAR BUILDING, 3 PARLIAMENT STREET, NEW DELHI - LTD 110001 BNP PARIBAS BNPA0009066 French Bank Bldg.,62, Homji Street, Mumbai - 400 001 CALYON BANK CRLY0000001 Hoechst House, 11th, 12th, 14th Floor, Nariman Point, Churchgate, Mumbai - 400 021. -

CRAMPED for ROOM Mumbai’S Land Woes

CRAMPED FOR ROOM Mumbai’s land woes A PICTURE OF CONGESTION I n T h i s I s s u e The Brabourne Stadium, and in the background the Ambassador About a City Hotel, seen from atop the Hilton 2 Towers at Nariman Point. The story of Mumbai, its journey from seven sparsely inhabited islands to a thriving urban metropolis home to 14 million people, traced over a thousand years. Land Reclamation – Modes & Methods 12 A description of the various reclamation techniques COVER PAGE currently in use. Land Mafia In the absence of open maidans 16 in which to play, gully cricket Why land in Mumbai is more expensive than anywhere SUMAN SAURABH seems to have become Mumbai’s in the world. favourite sport. The Way Out 20 Where Mumbai is headed, a pointer to the future. PHOTOGRAPHS BY ARTICLES AND DESIGN BY AKSHAY VIJ THE GATEWAY OF INDIA, AND IN THE BACKGROUND BOMBAY PORT. About a City THE STORY OF MUMBAI Seven islands. Septuplets - seven unborn babies, waddling in a womb. A womb that we know more ordinarily as the Arabian Sea. Tied by a thin vestige of earth and rock – an umbilical cord of sorts – to the motherland. A kind mother. A cruel mother. A mother that has indulged as much as it has denied. A mother that has typically left the identity of the father in doubt. Like a whore. To speak of fathers who have fought for the right to sire: with each new pretender has come a new name. The babies have juggled many monikers, reflected in the schizophrenia the city seems to suffer from. -

Reliance Foundation and Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai to Provide Three Lakh Free COVID-19 Vaccines for Mumbai’S Underprivileged Communities

MEDIA RELEASE Reliance Foundation and Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai to provide three lakh free COVID-19 vaccines for Mumbai’s underprivileged communities • Communities across 50 locations including Dharavi, Worli, Wadala, Colaba, Kamatipura, Chembur to be covered • Reliance Foundation through Sir H N Reliance Foundation Hospital is deploying state-of-the-art mobile vehicle unit for the vaccination drive • Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) and BEST provide infrastructure & logistics support Mumbai, 2nd August 2021: In a major outreach scheme to protect Mumbai’s vulnerable communities, Reliance Foundation through Sir H N Reliance Foundation Hospital will collaborate with Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) to provide three lakh COVID-19 vaccination doses to communities across 50 locations in Mumbai. This free vaccination drive aims to protect underprivileged people in neighbourhoods including Dharavi, Worli, Wadala, Colaba, Pratiksha Nagar, Kamatipura, Mankhurd, Chembur, Govandi and Bhandup. Sir H N Reliance Foundation Hospital is deploying a state-of-the-art mobile vehicle unit to conduct the vaccination drive across the selected locations of Mumbai, while MCGM and BEST will provide infrastructure and logistics support for the drive. This initiative builds on Sir HN Reliance Foundation Hospital’s regular health outreach initiatives in Mumbai, which address primary and preventive healthcare needs of vulnerable populations through mobile medical vans and static medical units. This vaccination programme will be carried out over the next three months and is part of Reliance Foundation’s Mission Vaccine Suraksha initiative which will also provide vaccination for underprivileged communities around the country over the next few months. Smt Nita M Ambani, Founder and Chairperson, Reliance Foundation said: “Reliance Foundation has stood by the nation at every step of this relentless fight against the COVID- 19 pandemic. -

Redharavi1.Pdf

Acknowledgements This document has emerged from a partnership of disparate groups of concerned individuals and organizations who have been engaged with the issue of exploring sustainable housing solutions in the city of Mumbai. The Kamala Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute of Architecture (KRVIA), which has compiled this document, contributed its professional expertise to a collaborative endeavour with Society for Promotion of Area Resource Centres (SPARC), an NGO involved with urban poverty. The discussion is an attempt to create a new language of sustainable urbanism and architecture for this metropolis. Thanks to the Dharavi Redevelopment Project (DRP) authorities for sharing all the drawings and information related to Dharavi. This project has been actively guided and supported by members of the National Slum Dwellers Federation (NSDF) and Dharavi Bachao Andolan: especially Jockin, John, Anand, Savita, Anjali, Raju Korde and residents’ associations who helped with on-site documentation and data collection, and also participated in the design process by giving regular inputs. The project has evolved in stages during which different teams of researchers have contributed. Researchers and professionals of KRVIA’s Design Cell who worked on the Dharavi Redevelopment Project were Deepti Talpade, Ninad Pandit and Namrata Kapoor, in the first phase; Aditya Sawant and Namrata Rao in the second phase; and Sujay Kumarji, Kairavi Dua and Bindi Vasavada in the third phase. Thanks to all of them. We express our gratitude to Sweden’s Royal University College of Fine Arts, Stockholm, (DHARAVI: Documenting Informalities ) and Kalpana Sharma (Rediscovering Dharavi ) as also Sundar Burra and Shirish Patel for permitting the use of their writings. -

Costal Road JTC.Pdf

CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 BACKGROUND 1.1 General: 1.2 Mumbai: Strengths and Constraints: 1.3 Transport Related Pollution: 1.4 Committee for Coastal Freeway: 1.5 Reference (TOR): 1.6 Meetings: CHAPTER 2 NEED OF A RING ROAD/ COASTAL FREEWAY FOR MUMBAI 2.1 Review of Past Studies: 2.2 Emphasis on CTS: 2.3 Transport Indicators 2.4 Share of Public Transport: 2.5 Congestion on Roads: 2.6 Coastal Freeways/ Ring Road: 2.7 Closer Examination of the Ring Road: 2.8 Reclamation Option: 2.9 CHAPTER 3 OPTIONS TOWARDS COMPOSITION OF COASTAL FREEWAY 3.1 Structural Options for Coastal Freeway: 3.2 Cost Economics: 3.3 Discussion regarding Options: 3.4 Scheme for Coastal Freeway: CHAPTER 4 COASTAL FREEWAY: SCHEME 4.1 4.2 Jagannath Bhosle Marg-NCPA(Nariman Point)-Malabar Hill-Haji Ali-Worli: 4.3 Bandra Worli: 4.4 Bandra Versova- Malad Stretch 4.5 Coastal road on the Gorai island to Virar: 4.6 Connectivity to Eastern Freeway: 4.7 Interchanges, Exits and Entries: 4.8 Widths of Roads and Reclamation: 4.9 Summary of the Scheme: 4.10 Schematic drawings of the alignment CHAPTER 5 ENVIRONMENTAL ASPECTS 5.1 Coastal Road Scheme: 5.2 Key Issue: Reclamation for Coastal Freeway: 5.3 Inputs received from CSIR-NIO: 5.4 Legislative Framework: 5.5 Further Studies: CHAPTER 6 POLICY INTERVENTIONS AND IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGY 6.1 Costs: 6.2 Funding and Construction through PPP/EPC Routes: 6.3 Maintenance Costs/ Funding: 6.4 Implementation Strategy: 6.5 Implementation Agency: 6.6 Construction Aspects: 6.7 Gardens, Green Spaces and Facilities: 6.8 Maintenance and Asset Management: CHAPTER -

Study of Housing Typologies in Mumbai

HOUSING TYPOLOGIES IN MUMBAI CRIT May 2007 HOUSING TYPOLOGIES IN MUMBAI CRIT May 2007 1 Research Team Prasad Shetty Rupali Gupte Ritesh Patil Aparna Parikh Neha Sabnis Benita Menezes CRIT would like to thank the Urban Age Programme, London School of Economics for providing financial support for this project. CRIT would also like to thank Yogita Lokhande, Chitra Venkatramani and Ubaid Ansari for their contributions in this project. Front Cover: Street in Fanaswadi, Inner City Area of Mumbai 2 Study of House Types in Mumbai As any other urban area with a dense history, Mumbai has several kinds of house types developed over various stages of its history. However, unlike in the case of many other cities all over the world, each one of its residences is invariably occupied by the city dwellers of this metropolis. Nothing is wasted or abandoned as old, unfitting, or dilapidated in this colossal economy. The housing condition of today’s Mumbai can be discussed through its various kinds of housing types, which form a bulk of the city’s lived spaces This study is intended towards making a compilation of house types in (and wherever relevant; around) Mumbai. House Type here means a generic representative form that helps in conceptualising all the houses that such a form represents. It is not a specific design executed by any important architect, which would be a-typical or unique. It is a form that is generated in a specific cultural epoch/condition. This generic ‘type’ can further have several variations and could be interestingly designed /interpreted / transformed by architects. -

A Case Study of Versova Bandra Sea Link

TRAVEL DEMAND FORECASTING FOR AN URBAN FREEWAYCORRIDOR: A CASE STUDY OF VERSOVA BANDRA SEA LINK CH SEKHARA RAO MOJJADA, CIVIL ENGINEERING SECTION, ONGC, GOA, [email protected] DHINGRA S L, INSTITUTE CHAIR PROFESSOR, IIT BOMBAY, [email protected] SRINIVAS G, TRANSPORTATION PLANNER, IBI GROUP, [email protected] This is an abridged version of the paper presented at the conference. The full version is being submitted elsewhere. Details on the full paper can be obtained from the author. Travel Demand Forecasting for an Urban Freeway Corridor: A case study of Versova Bandra Sea Link Ch Sekhara Rao, Mojjada; Dhingra, S L; Srinivas, G TRAVEL DEMAND FORECASTING FOR AN URBAN FREEWAYCORRIDOR: A CASE STUDY OF VERSOVA BANDRA SEA LINK Ch Sekhara Rao Mojjada, Civil Engineering Section, ONGC, Goa, [email protected] Dhingra S L, Institute Chair Professor, IIT Bombay, [email protected] Srinivas G, Transportation Planner, IBI Group, [email protected] ABSTRACT Transport demand is growing drastically in Indian cities due to increase in urbanization and migration from rural areas and smaller towns. Increase in household income, increase in commercial and industrial activities has further added to transport demand in metropolitan regions like Mumbai Metro Politian Region (MMR). Hence India is concentrating more on the urban infrastructure like construction of many expressways, freeways, BRTS etc. to accommodate the rapidly growing urbanization and also to get relieved from congestion. Many a times the geographical constraints also limit the opportunities for creating the infrastructure and force the government to build the transport infrastructure with very high investment through various PPR (Public Private Partnership) model. -

No. Sub Division Designation,Address & Telephone

No. Sub Division Designation,Address & Designation,Address & Designation,Address & Telephone Telephone Number of Assistant Telephone Number of Number of Government Information Information Officer Government Information Officer Officer 1 Office of the 1] Administrative Officer,Desk -1 1] Assistant Commissiner 1] Deputy Commissiner of Commissioner of {Confidential Br.},Office of the of Police,{Head Quarter- Police,{Head Quarter-1},Office of the Police,Mumbai Commissioner of Police, 1},Office of the Commissioner of Police, D.N.Road, D.N.Road,Mumbai-01,Telephone Commissioner of Police, Mumbai-01,Telephone No.2620043 No.22695451 D.N.Road, Mumbai-01, Telephone No.22624426 Confidential Report, Sr.Esstt., 2] Sr.Administrative Officer, Assistant Commissiner of Deputy Commissiner of Police, {Head Dept.Enquiry, Pay, Desk-3 {Sr.Esstt. Br.}, Office of Police, {Head Quarter- Quarter-1},Office of the Commissioner Licence, Welfare, the Commissioner of Police, 1},Office of the of Police, D.N.Road, Mumbai- Budget, Salary, D.N.Road,Mumbai-01, Telephone Commissioner of Police, 01,Telephone No.2620043 Retirdment No.22620810 D.N.Road, Mumbai-01, etc.Branches Telephone No.22624426 3] Sr.Administrative Officer,Desk - Assistant Commissiner of Deputy Commissiner of Police, {Head 5 {Dept.Enquiry} Br., Office of the Police, {Head Quarter- Quarter-1},Office of the Commissioner Commissioner of Police, 1},Office of the of Police, D.N.Road, Mumbai- D.N.Road,Mumbai-01,Telephone Commissioner of Police, 01,Telephone No.2620043 No.22611211 D.N.Road, Mumbai-01, Telephone -

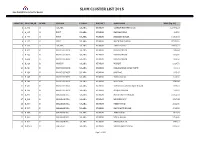

List of Slum Cluster 2015

SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. M.) 1 A_001 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GANESH MURTHI NAGAR 120771.23 2 A_005 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI BANGALIPURA 318.50 3 A_006 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI NARIMAN NAGAR 14315.98 4 A_007 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI MACHIMAR NAGAR 37181.09 5 A_009 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GEETA NAGAR 26501.21 6 B_021 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 939.53 7 B_022 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 1292.90 8 B_023 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 318.67 9 B_029 B MANDVI COLABA MUMBAI MANDVI 1324.71 10 B_034 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI NALABANDAR JOPAD PATTI 600.14 11 B_039 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI JHOPDAS 908.47 12 B_045 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI INDRA NAGAR 1026.09 13 B_046 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MAZGAON 1541.46 14 B_047 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI SUBHASHCHANDRA BOSE NAGAR 848.16 15 B_049 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MASJID BANDAR 277.27 16 D_001 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI MATA PARVATI NAGAR 21352.02 17 D_003 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI BRANHDHARY 1597.88 18 D_006 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI PREM NAGAR 3211.09 19 D_007 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI NAVSHANTI NAGAR 4013.82 20 D_008 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI ASHA NAGAR 1899.04 21 D_009 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SIMLA NAGAR 9706.69 22 D_010 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SHIVAJI NAGAR 1841.12 23 D_015A D GIRGAUM COLABA MUMBAI SIDHDHARTH NAGAR 2189.50 Page 1 of 101 SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. -

Total List of MCGM and Private Facilities.Xlsx

MUNICIPAL CORPORATION OF GREATER MUMBAI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARIES SR SR WARD NAME OF THE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY ADDRESS NO NO 1 1 COLABA MUNICIPALMUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 1ST FLOOR, COLOBA MARKET, LALA NIGAM ROAD, COLABA MUMBAI 400 005 SABOO SIDIQUE RD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY ( 2 2 SABU SIDDIQ ROAD, MUMBAI (UPGRADED) PALTAN RD.) 3 3 MARUTI LANE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY MARUTI LANE,MUMBAI A 4 4 S B S ROAD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 308, SHAHID BHAGATSINGH MARG, FORT, MUMBAI - 1. 5 5 HEAD OFFICE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY HEAD OFFICE BUILDING, 2ND FLOOR, ANNEX BUILDING, MUMBAI - 1, 6 6 HEAD OFFICE AYURVEDIC MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY HEAD OFFICE BUILDING, 2ND FLOOR, ANNEX BUILDING, MUMBAI - 1, 7 1 SVP RD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 259, SARDAR VALLABBHAI PATEL MARG, QUARTERS, A BLOCK, MAUJI RATHOD RD, NOOR BAUG, DONGRI, MUMBAI 400 8 2 WALPAKHADI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 009 9B 3 JAIL RD. UNANI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 259, SARDAR VALLABBHAI PATEL MARG, 10 4 KOLSA MOHALLA MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 20, KOLSA STREET, KOLSA MOHALLA UNANI , PAYDHUNI 11 5 JAIL RD MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 20, KOLSA STREET, KOLSA MOHALLA UNANI , PAYDHUNI CHANDANWADI SCHOOL, GR.FLOOR,CHANDANWADI,76-SHRIKANT PALEKAR 12 1 CHANDAN WADI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY MARG,MARINELINES,MUM-002 13 2 THAKURDWAR MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY THAKURDWAR NAKA,MARINELINES,MUM-002 C PANJRAPOLE HEALTH POST, RAMA GALLI,2ND CROSS LANE,DUNCAN ROAD 14 3 PANJRAPOLE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY MUMBAI - 400004 15 4 DUNCAN RD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY DUNCAN ROAD, 2ND CROSS GULLY 16 5 GHOGARI MOHALLA MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY HAJI HASAN AHMED BAZAR MARG, GOGRI MOHOLLA 17 1 NANA CHOWK MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY NANA CHOWK, FIRE BRIGADE COMPOUND, BYCULLA 18 2 R. S. NIMKAR MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY R.S NIMKAR MARG, FORAS ROAD, 19 3 R.