CHAPTER 6 : the Historical Background to Ticket Rage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Official Anzac Friendship Match

THE OFFICIAL ANZAC FRIENDSHIP MATCH 27th of April 2013 VIETNAM SWANS vs JAKARTA BINTANGS LORD MAYOR’S OVAL, VUNG TAU FEATURES 02 WELCOMES Messages from all those involved and those with a past history with the ANZAC Friendship Match. 30 THE HISTORY OF See the photo THE VFL that caused a stir Stan Middleton tells us on the Vietnam about the Vietnam Football Swans’ website. League. page 56. 34 AROUND THE GROUNDS Stories from other countries and thier ANZAC matches 40 BROTHER CLUBS Clubs from Australia give their best for the weekend. 45 TWO BLACK ARMBANDS Remembering the fallen 46 SCHEDULE A rundown of the ANZAC Weekend. 48 TEAM PROFILES Read up about the players of this historic match. 03 58 CHARITIES PHIL JOHNS The young lives we are Vietnam Swans supporting at today’s National President ANZAC Friendship Match. welcomes all to this great occassion. FRONT COVER Kevin Back & Bob McKenna, October 1968 THE 2013 ANZAC FRIENDSHIP MATCH RECORD - 01 Welcomes & Messages John McAnulty Australian Consul General, HCMC would like to welcome you to the 4th Annual ANZAC Friendship Weekend in Vung Tau. It is my honour to be involved in an event Ithat celebrates the close relationship between Australia and Vietnam especially with this year being the 40th Anniversary of Diplomatic Relations between our two countries. A 40 year partnership marked by friendship and cooperation and which continues to strengthen. This week Australians paused to remember the sacrifices made by their compatriots – from the beaches of Gallipoli to the fields of Northern France, from Tobruk to Kokoda and in Korea and Vietnam and in more recent theatres in East Timor, Iraq and Afghanistan. -

Encyclopedia of Australian Football Clubs

Full Points Footy ENCYCLOPEDIA OF AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL CLUBS Volume One by John Devaney Published in Great Britain by Full Points Publications © John Devaney and Full Points Publications 2008 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission. Every effort has been made to ensure that this book is free from error or omissions. However, the Publisher and Author, or their respective employees or agents, shall not accept responsibility for injury, loss or damage occasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of material in this book whether or not such injury, loss or damage is in any way due to any negligent act or omission, breach of duty or default on the part of the Publisher, Author or their respective employees or agents. Cataloguing-in-Publication data: The Full Points Footy Encyclopedia Of Australian Football Clubs Volume One ISBN 978-0-9556897-0-3 1. Australian football—Encyclopedias. 2. Australian football—Clubs. 3. Sports—Australian football—History. I. Devaney, John. Full Points Footy http://www.fullpointsfooty.net Introduction For most football devotees, clubs are the lenses through which they view the game, colouring and shaping their perception of it more than all other factors combined. To use another overblown metaphor, clubs are also the essential fabric out of which the rich, variegated tapestry of the game’s history has been woven. -

A BRIEF HISTORY 1892 Metropolitan Junior Football Association Began at Salvation Army Headquarters, 62 Bourke Street, Melbourne

A BRIEF HISTORY 1892 Metropolitan Junior Football Association began at Salvation Army Headquarters, 62 Bourke Street, Melbourne. W.H. Davis, first President and E.R. Gower, first Secretary. Alberton, Brighton, Collegians, Footscray District, St. Jude’s, St. Mary’s, Toorak-Grosvenor and Y.M.C.A. made up the Association. 1893 Olinda F.C., University 2nd and South St. Kilda admitted. 1894 Nunawading F.C., Scotch Collegians, Windsor and Caulfield admitted. Olinda F.C., University 2nd, Footscray District and St. Jude’s withdrew. 1895 Waltham F.C. admitted. Toorak-Grosvenor Y.M.C.A. disbanded. 1896 Old Melburnians and Malvern admitted. Alberton and Scotch Collegians withdrew. L.A. Adamson elected second President. 1897 V.F.L. formed. M.J.F.A. received 2 pounds 12 shillings and 6 pence as share of gate receipts from match games against Fitzroy. Result Fitzroy 5.16 defeated M.J.F.A. 3.11. South Yarra and Booroondara admitted, Old Melburnians withdrew. Waltham disbanded 15/6/97. Booroondara withdrew at end of season. 1898 Leopold and Beverley admitted. St. Mary’s banned from competition 7/6/1898. 1899 Top two sides played off for Premiership. J.V. (Val) Deane appointed Secretary. Parkville and St. Francis Xaviers admitted, St. Francis Xaviers disbanded in May 1899 and Kew F.C. chose to play its remaining matches. 1900 South Melbourne Juniors admitted. 1904 Fitzroy District Club admitted. 1905 Melbourne University F.C. admitted due to amalgamation of Booroondara and Hawthorn. 1906 Fitzroy District changed name to Collingwood Districts and played at Victoria Park. Melbourne District Football Association approached to affiliate with M.J.F.A. -

Tasmanian Football Companion

Full Points Footy’s Tasmanian Football Companion by John Devaney Full Points Footy http://www.fullpointsfooty.net © John Devaney and Full Points Publications 2009 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission. Every effort has been made to ensure that this book is free from error or omissions. However, the Publisher and Author, or their respective employees or agents, shall not accept responsibility for injury, loss or damage occasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of material in this book whether or not such injury, loss or damage is in any way due to any negligent act or omission, breach of duty or default on the part of the Publisher, Author or their respective employees or agents. Cataloguing-in-Publication data: Full Points Footy’s Tasmanian Football Companion ISBN 978-0-9556897-4-1 1. Australian football—Encyclopedias. 2. Australian football—Tasmania. 3. Sports—Australian football—History. I. Devaney, John. Full Points Footy http://www.fullpointsfooty.net Acknowledgements I am indebted to Len Colquhoun for providing me with regular news and information about Tasmanian football, to Ross Smith for sharing many of the fruits of his research, and to Dave Harding for notifying me of each season’s important results and Medal winners in so timely a fashion. Special thanks to Dan Garlick of OzVox Media for permission to use his photos of recent Southern Football League action and teams, and to Jenny Waugh for supplying the photo of Cananore’s 1913 premiership-winning side which appears on page 128. -

Bumper AFL Grand Final Week on Seven

Bumper AFL Grand Final week on Seven Local Grand Finals, The Chosen Few and Grand Final Eve countdown (23 September, 2015) From the best football news and analysis to the Brownlow Medal, the traditional Grand Final Eve marathon and the LIVE and EXCLUSIVE 2015 AFL Grand Final, Seven has all the action covered in the fevered build-up in football’s biggest week. Seven Sport’s Grand Final day coverage will include Bruce McAvaney, Dennis Cometti, Brian Taylor, Tim Watson, Leigh Matthews, Cameron Ling, Luke Darcy, Matthew Richardson, Wayne Carey, Hamish McLachlan, Basil Zempilas, Nick Maxwell and Andrew Welsh, along with Sam Lane and Mick Molloy. Long before the first bounce, Seven will launch into a week-long celebration of Australia’s favourite football code, starting with Game Day on Sunday morning after the two grand finalists have booked a berth in the AFL’s ultimate decider. Sunday September 27 AFL GAME DAY – 10am on Channel 7 in Melb, Adel and Perth and 7mate in Syd and Bris Hamish McLachlan hosts Game Day to preview and analyse the biggest week on the AFL calendar with Leigh Matthews, Jimmy Bartel and Andrew Welsh. VFL Grand Final – Box Hill v Williamstown (Etihad Stadium) – 2.30pm LIVE on Channel 7 in VIC SANFL Grand Final – Eagles v West Adelaide (Adelaide Oval) – 1.30pm LIVE on Channel 7 in SA WAFL Grand Final – Subiaco v West Perth (Domain Stadium) – 2pm LIVE on Channel 7 in WA Monday September 28 AFL BROWNLOW MEDAL On Monday night the Brownlow screens live on Seven, starting with an expanded, fashion-focused Brownlow Red Carpet Special at 7.30pm, co-hosted by Hamish McLachlan and Rebecca Maddern with Rachael Finch and Andrew Welsh. -

November 2014

NOVEMBER 2014 Registered by Australia Post Publication No.PP 5321/51/0003 Principal’s Report Dear Members of the Sacred Heart College Community As I write, the Class of 2014 is in their concluding week of classes. So, after over 500 weeks of schooling our Year 12 students’ lives move into a phase CONTENTS very different to the routines to which Features they have been accustomed. I’m sure 2 Principal’s Report many readers have fond memories of 3 Chairman’s Report their time associated as students or as parents (or both!) of the College. School News The Class of 2014 will soon be 4 Academic Achievements Sacred Heart Old Collegians, but 4 Yr 12 Formal perhaps not that old! 6-7 Co-curricular News Steve Byrne 8-9 Dance/Music/Drama Since the first edition of the Blue and Blue much has been 10-14 School Sports accomplished and a significant, if not historical, decision 15 Boarding House News has been taken to combine the previously separately administered Sacred 16 P&F News Heart College Senior and Middle Schools to form a single entity - Sacred Foundation Office Heart College - from 2015. 18 Chairman’s Report The decision followed extensive consultation across the two schools and was 18 Centenary Celebrations inclusive of all stakeholders. Paul Herrick, Director (Melbourne Region), Marist 22 Sacred Sights 4WD Tour Schools Australia (MSA), in his letter to the Sacred Heart Community back in Sacred Heart Old Collegians Association August put it thus:- 24 President’s Report ‘Formal consultations were conducted with the staff of both Schools, with the Advisory Councils of both Schools, with the SHC Foundation, with the Old 25 SHOC’s Annual Business Lunch Scholars, and with the Archdiocese. -

Port Melbourne Williamstown

Peter Jackson VFL Grand Final PORT MELBOURNE WILLIAMSTOWN VFL & TAC CUP GRAND FINAL EDITION AFL VICTORIA SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 25, 2011 TAC Cup Grand Final SANDRINGHAMHAM DRAGONSD OAKLEIGHH CCHARGERSHA ALL-NEW RANGER Ready to take on the world Tested to the limits and beyond Meet the team and the locations that pushed the all-new Ranger to the limits and beyond at ford.com.au/newranger Pre-production 4x4 XLT Crew Cab shown in Aurora Blue. Appearance may change at time of introduction. editorial Season fi nale The race for the premiership started with 25 teams across two competitions - just two will hold aloft the premiership cup at the end of another season. WELCOME to one of the truly to win the premiership is North Cup Coaches Award. great and traditional days in the Melbourne in 1918. AFL Victoria is appreciative of Victorian sporting calendar – the Victoria’s talented player pathway all the hard work and energy twin bill Peter Jackson VFL and program is something which AFL delivered by volunteers at TAC Cup Grand Finals. Victoria is extremely proud. The every club in the Peter Jackson It’s a celebration and climax of title of the best State in the NAB VFL and TAC Cup. It is that yet another memorable season, AFL U18 Championships was commitment and passion that clustered with highlights, both won by Vic Metro – it is the 16th drives our great game. club and individual. time since 1991 a Victorian team Clearly, the value of partners And, it showcases some of has won the Championship. can’t be understated. -

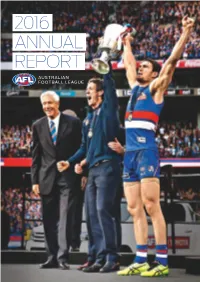

2016 Annual Report

2016 ANNUAL REPORT AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE CONTENTS AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE 120TH ANNUAL REPORT 2016 4 2016 Highlights 16 Chairman’s Report 30 CEO’s Report 42 AFL Clubs & Operations 52 Football Operations 64 Commercial Operations 78 NAB AFL Women’s 86 Game & Market Development 103 Around The Regions 106 AFL in Community 112 Legal & Integrity 120 AFL Media 126 Awards, Results & Farewells 139 Obituaries 142 Financial Report 148 Concise Financial Report Western Bulldogs coach Cover: The wait is over ... Luke Beveridge presents Luke Beveridge (obscured), his Jock McHale Medal Robert Murphy and captain to injured skipper Robert Easton Wood raise the Murphy, a touching premiership cup, which was gesture that earned him a presented by club legend Spirit of Australia award. John Schultz (left). 99,981 The attendance at the 2016 Toyota AFL Grand Final. 4,121,368 The average national audience for the 2016 Toyota AFL Grand Final on the Seven Network which made the Grand Final the most watched program of any kind on Australian television in 2016. This total was made up of a five mainland capital city metropolitan average audience of 3,070,496 and an average audience of 1,050,872 throughout regional Australia. 18,368,305 The gross cumulative television audience on the Seven Network and Fox Footy for the 2016 Toyota AFL Finals Series which was the highest gross cumulative audience for a finals series in the history of the AFL/VFL. The Bulldogs’ 62-year premiership drought came to an end in an enthralling Grand Final, much to the delight of young champion Marcus Bontempelli and delirious 4 Dogs supporters. -

52026 Mission Melbourne Fact Sheet

TRAVEL WITH CHRIS BROWN MELBOURNE UNFORGETTABLE EXPERIENCES Its travel with a twist this week as Amanda sends Chris on an unforgettable trip to Melbourne. It has been voted most livable city in the world two years running but that’s not why Chris is there. Armed with a list of challenges that Amanda has set, Chris makes his mark on the city courtesy of a graffiti art project and joins a training session with some of Melbourne’s fittest men, the St Kilda Saints. Then it’s off to Fitzroy’s famous Kodiak bar for a ‘Hot Wings Challenge’ against local competitive eating champion ‘Hungry Haddo’. It’s travel day that Chris will never forget! TRAM SESSIONS Tram Sessions, a not-for-porfit project is the creation of Sweden study-exchange students Nick Walberg and Carl Mamsten. Inspired by Black Cab Sessions in London and Take- Away Shows on La Blogotheque in Paris, both of which feature artists performing outside their typical comfort zone. Starting off in true guerrilla style with a 2010 pilot that roped in a friend as performer, the duo soon had the approval of Yarra Trams. But beyond the presentation and a simple idea that is so very ‘Melbourne’, Tram Sessions is about the Victorian capital in another, more specific way. Over the last five years, Melburnians have watched as an increasing number of inner city live music venues have closed their doors. The Trams Session’s Statement of Purpose: • to encourage the use of sustainable transport by letting Melbourne artists and bacnds perfor on city trams. -

2017 Premiers CONTENTS AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE 121ST ANNUAL REPORT 2017

Australian Football League Annual Report 2017 Premiers CONTENTS AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE 121ST ANNUAL REPORT 2017 4 2017 Highlights 16 Chairman’s Report 26 CEO’s Report 36 Strong Clubs 44 Spectacular Game 68 Revenue/Investment 80 Financial Report 96 Community Football 124 Growth/Fans 138 People 144 Awards, Results & Farewells Cover: The 37-year wait is over for Richmond as coach Damien Hardwick and captain Trent Cotchin raise the premiership cup; co-captains Chelsea Randall and Erin Phillips with coach Bec Goddard after the Adelaide Crows’ historic NAB AFLW Grand Final win. Back Cover: Richmond star Jack Riewoldt joining US Jubilant Richmond band The Killers on fans erupt around the stage at the Grand MCG at the final siren Final Premiership as the Tigers clinch Party was music their first premiership to the ears of since 1980. Tiger fans. 100,021 The attendance at the 2017 Toyota AFL Grand Final 3,562,254 The average national audience on the Seven Network for the 2017 Toyota AFL Grand Final, which was the most watched program of any kind on Australian television in 2017. This was made up by an audience of 2,714,870 in the five mainland capital cities and an audience in regional Australia of 847,384. 16,904,867 The gross cumulative audience on the Seven Network and Fox Footy Channel for the 2017 Toyota AFL Finals Series. Richmond players celebrate after defeating the Adelaide Crows in the 2017 Toyota AFL Grand Final, 4 breaking a 37-year premiership drought. 6,732,601 The total attendance for the 2017 Toyota AFL Premiership Season which was a record, beating the previous mark of 6,525,071 set in 2011. -

Department of Economics Issn 1441-5429 Discussion

DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS ISSN 1441-5429 DISCUSSION PAPER 21/05 SOME ECONOMIC EFFECTS OF CHANGES TO GATE-SHARING ARRANGEMENTS IN THE AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE Ross Booth 1 SOME ECONOMIC EFFECTS OF CHANGES TO GATE-SHARING ARRANGEMENTS IN THE AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE 1 INTRODUCTION Whilst gate revenue as a source of revenue for the (member-owned win-maximising) clubs in the Australian Football League (AFL) is relatively small and declining as a proportion, it is still an important source of revenue difference between clubs, and potentially their on-field playing performance. Until 2000, gate revenue was shared between the home and away teams (after the deduction of match expenses), after which the policy was changed to allow the home team to keep all of the (net) gate receipts. In the AFL, membership income, reserved seat and corporate box income has never been shared, but the league does share the revenue from key income streams such as national TV broadcast rights (there is no local TV revenue), corporate sponsorship and finals. The AFL (1998) recommended in its Gate Sharing Discussion Paper to change the gate-sharing arrangements, because the intended equalising of gate revenue was not being achieved. Whilst net gate proceeds had traditionally been shared 50-50, membership and reserved seat income had not. This meant that a club playing in a large stadium with a large cash-paying crowd provided a good return for the visiting side. However, a club playing in a small stadium filled mostly with members and reserved seat holders had little room for a cash-paying crowd, and hence provided a poor return to the visiting team. -

2008 Yearbook Port Adelaide Football Club

14 28 54 Contents 2008 Yearbook Port Adelaide Football Club 2 PRESIDENT’S REPORT 34 KANE’S COMING OF AGE Greg Boulton Best & Fairest wrap 4 MEET THE BOARD 42 PLAYER REVIEWS 2008 Board of Directors Analysis of every player INTRODUCING OUR ALLAN SCOTT AO, OAM Cover: 2008 John Cahill Medallist 5 47 Kane Cornes. Read more about NEW PRESIDENT Giving thanks to Allan Scott Kane’s Coming of Age on page 34. Q & A with Brett Duncanson ROBERT BERRIMA QUINN Cover design: EnvyUs Design 48 Cover photography: AFL Photos 7 CEO’S REPORT Paying homage to one of Power Brand Manager: Jehad Ali Mark Haysman our all time greats Port Adelaide Football Club Ltd COACH’S REPORT THE COMMUNITY CLUB 10 50 Brougham Place Alberton SA 5014 Mark Williams The Power in the community Postal Adress: PO Box 379 Port Adelaide SA 5015 Phone: 08 8447 4044 Fax: 08 8447 8633 ROUND BY ROUND CLUB RECORDS 14 54 [email protected] PortAdelaideFC.com.au 2008 Season Review 1870-2008 Design & Print by Lane Print & Post Pty Ltd NEW LOOK FOR ‘09 SANFL/AFL HONOUR ROLL 22 60 101 Mooringe Avenue Camden Park SA 5038 Membership Strategy 1870-2008 Phone: 08 8179 9900 Fax: 08 8376 1044 25 ALL THE STATS 62 STAFF LIST [email protected] LanePrint.com.au Every player’s numbers 2008 Board, management Yearbook 2008 is an offi cial publication from 2008 staff and support staff list of the Port Adelaide Football Club President Greg Boulton 26 2008 PLAYER LIST 64 LIFE MEMBERS Chief Executive Mark Haysman Games played for 2008 1909-2008 Editors Daniel Norton, Andrew Fuss Writers Daniel Bryant, Andrew Fuss, Daniel Norton 28 OUR HEART AND SOUL THE NUMBERS Photography AFL Photos, Gainsborough Studios, A tribute to Michael Wilson PAFC FINANCIALS FOR 2008 Bryan Charlton, The Advertiser 65 -Notice of AGM THANKS FOR THE MEMORIES 30 - Directors’ Report Copyright of this publication belongs to the Port Adelaide Football Club Ltd.