Water-Policy Study Represented in This Paper Is Jointly Sponsored by the Two Cities and Is Linked to Cooperation Concerning an ETJ Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agenda 02.19.13

AGENDA PUBLIC HEARING February 19, 2013 Capitol Extension, E2.010 7:30 a.m. I. CALL TO ORDER & ROLL CALL II. HB 4 Ritter Relating to the creation and funding of the state water implementation fund for Texas to assist the Texas Water Development Board in the funding of certain water- related projects. III. INVITED TESTIMONY ON HB 4 A. Panel One: Mayors (To Be Called As Available) Annise Parker, Mayor of Houston Mike Rawlings, Mayor of Dallas John Monaco, Mayor of Mesquite, President of TML Lee Leffingwell, Mayor of Austin John Cook, Mayor of El Paso Julian Castro, Mayor of San Antonio B. Panel Two: Legislative Budget Board Patrick Moore, Analyst C. Panel Three: Averitt & Associates Kip Averitt, Principal D. Panel Four: Texas Water Development Board Melanie Callahan, Executive Administrator Piper Montemayor, Director in Finance for Debt & Portfolio Management Carolyn Brittin, Deputy Executive Administrator, Water Resources Planning and Information E. Panel Five: Estrada Hinojosa & Company, Inc. Jorge A. Garza, Senior Managing Director F. Panel Six: West Texas Mayors Norm Archibald, Mayor of Abilene Wes Perry, Mayor of Midland Alvin New, Mayor of San Angelo G. Panel Seven: H2O 4 Texas Coalition Heather Harward, Executive Director H. Panel Eight: Water Associations Dean Robbins, General Manager Texas Water Conservation Association Carol Batterton, Executive Director Water Environment Association of Texas Fred Aus, Executive Director Texas Rural Water Association Page 1 of 2 I. Panel Nine: River Authorities Becky Motal, General Manager Lower Colorado River Authority Kevin Ward, General Manager Trinity River Authority Bill West, General Manager Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority J. Panel Ten: Water Utilities and Water Districts Robert Puente, CEO San Antonio Water Systems Jim Parks, General Manager North Texas Municipal Water District K. -

The Edwards Aquifer (Part A)

E-PARCC COLLABORATIVE GOVERNANCE INITIATIVE Program for the Advancement of SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY Maxwell School Research on Conflict and Collaboration THE EDWARDS AQUIFER (PART A) Amidst of one of the worst Texas droughts in recent memory, attorney Robert Gulley wondered why he had left his position at an established law practice to take on the position of program director for the Edwards Aquifer Recovery Implementation Program (EARIP). As the program director, Robert now worked for 26 different organizations and his job was to assist them, using a consensus-based stakeholder process, through one of the most contentious and intractable national disputes involving scarce groundwater resources at the Edwards Aquifer, one of the most valuable water resources in the Central Texas area. This dispute had already spanned decades and, to make this task even more daunting, the competing interests on both sides had made numerous unsuccessful attempts over the years to resolve this conflict. Hot weather, droughts, and the resulting conflicts between stakeholders are frequent occurrences in Texas. Robert, who had returned to his home state specifically for this position, knew that this drought would only intensify the tensions amongst the stakeholders involved. The Edwards Aquifer (“Aquifer”) provides approximately 90 percent of the water for over two million people living and working in the South-Central Texas area. The Aquifer supplies the water that services the city of San Antonio and other municipalities; a multi-million agricultural and ranching industry in the western part of the region that views water as a coveted property right; as well as the recreational activities that provide the backbone of the economies of rapidly-growing, nearby cities of San Marcos and New Braunfels (Figure 1). -

HRC's Gay Rights Ad During

APril 1[1[17 The Mar-qui§e P.O. Box 701204 WtiAT~§ 1~§1[)~ San Antonio, Texas 78232 ElESJAJ (210) 545-3511 Voice & Fax Quote-Unquote 4 E-mail: [email protected] The Marquise staff's favorite quotes for April. r:>ubllshe.- Bill Thornton for Mayor 5 & Manaulnlt l:dltf)l" The San Antonio Equal Rights Political Caucus endorses Bill Ted Switzer Thornton for re-election as mayor. J>I"C)duc:tlf)n l:dltf)l" AIDS in Bexar County 5 Heather Chandler The External Review Committee of the AIDS Consortium hands out over $1 million to local AIDS Agencies and a quick 4ssf)date l:dltf)I"S ............. c-.....,. review of some interesting statistics. Cllarcla oiS.. AatOIIIo Tere Frederickson Glenn Stehle The Cover: Page 6 , 4sslstant l:dltf)l" Human Rights Campaign ;·.,_ Our largest and most effective national ........ _ Wai7:00JB Michael Leal ~ ....,... organization started with a disconnected ...... CC)P'Y 4sslstant"S phone and $9 in the bank . ....... ...... Cheryl Fox -- Pictured on the cover are (clockwise from David Walsh CtllllllliDa17,_. ••a... Ctlfth af.. tln£C. bottom left) HRC Executive Director ~ \ ,.. ......lnetjce .... eccepta aD ...... J>hC)tf)ltl"aPhe.-s Elizabeth Birch, National Field Director " Donna Red Wing, National Governors 611 E. Myrtle (210) 472-3597 "' Linda Alvarado It's more than a party. Jo~ Salazar, Stephen Strausser Mark Phariss and Priscilla Magouirk. It's an experience. SALGA Update 6 You'll have something CC)nt.-lbutf)I"S A new name, a new meeting time,·but the same old disregard Rob Blanchard, David Bianco for the democratic process. -

CHRONOLOGICAL SUMMARY San Antonio's Struggle Over

CHRONOLOGICAL SUMMARY San Antonio’s Struggle Over Construction of the PGA Golf and Hotel Resort Over Sensitive Recharge Zone of the Edwards Aquifer May 2009 CHRONOLOGICAL SUMMARY San Antonio’s Struggle Over Construction of the PGA Golf and Hotel Resort Over Sensitive Recharge Zone of the Edwards Aquifer This chronological summary is drawn from contemporaneous1 articles that appeared in the San Antonio Express-News on the dates cited to the left of the chronicle. The page number and section of the paper in which the article appeared is noted in parenthesis. All quotations are drawn from the cited pieces, written by Express-News staff writers or, when noted, by Express-News columnists or the paper’s editorial board. PRE-PGA 1984 Oct. 17, 2001 (1H) Lumbermen’s invests $6.8 million in water for development put on indefinite hold after market collapse “In 1984, Lumbermen's paid $6.8 million in general benefit fees to the San Antonio Water System for pumping costs, storage capacity, main water lines and an extension of the sewer main. Shortly thereafter, the real estate market collapsed and the plan was put on hold. Nothing new had been proposed for the site until this year, when developers secured legislation allowing for a special taxing district to support infrastructure costs. The district is contingent on a development agreement with the city of San Antonio.” 1994 Jan. 26, 2002 (1B) Lumbermen’s and 26 other developments exploit loophole in water quality ordinance, “grandfathering” rights that exempt them from new restrictions on development over the aquifer. In 1994 City Council engaged in a “rancorous battle” over a proposal to safeguard San Antonio’s drinking water by establishing limits on development over the Edwards Aquifer. -

Texas Health Resources Foundation | 2018 Donor Giving TEXAS HEALTH RESOURCES FOUNDATION | 2018 DONOR GIVING 2

Texas Health Resources Foundation | 2018 Donor Giving TEXAS HEALTH RESOURCES FOUNDATION | 2018 DONOR GIVING 2 Contents 3 Hawthorne Society 4 Farrington-Thompson Society 5 Circle of Giving Society 9 Foundation Friends 29 Gifts-In-Kind 30 Birthday Buddies 31 Stewardship Report Texas Health Resources Foundation has made every attempt to ensure the completeness and accuracy of this list. If you notice an error or omission, please report it to the Foundation at 682-236-5200 and accept our sincere apologies. TEXAS HEALTH RESOURCES FOUNDATION | 2018 DONOR GIVING 3 Deepest appreciation is extended to the individuals, corporations, Crystelle Waggoner Charitable Trust, Rhoda and Howard L. Bernstein foundations and community organizations for all philanthropic Bank of America Trustee Blackwell Publishing, Inc. The Dallas Foundation BNSF Railway Company gifts supporting Texas Health Resources Foundation between Davidson Family Charitable Foundation Mr. and Mrs. Charles W. Boes January 1, 2018 and December 31, 2018. Veeta H. and C. J. (Red) Davidson Lorin A. Boswell Foundation Sherry and Howard Dudley Ann and Robert W. Bowman EMC of TeamHealth Nannie Hogan Boyd Trust Ethicon Endo-Surgery A. Compton Broders III, M.D. Mr. and Mrs. Finley Ewing III and Maureen Murry, M.D., J.D. Mrs. Gail Ewing Mrs. Sharon Marr Brown Hawthorne Society Dr. and Mrs. Maynard F. Ewton Jr. Burlington Resources Foundation Mr. and Mrs. Jerry Farrington Dr. and Mrs. Jeffrey L. Canose Below we list those special donors who have made Gerald J. Ford Family Foundation Carnival Minyard Foundation cumulative gifts of $100,000 or more since Texas Health Mr. and Mrs. Gerald J. -

Bluegrass Student Union

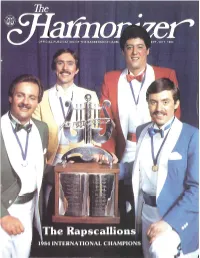

Bluegrass Student Union "+lave you seel1 •You cal1 9Qt tilt heW ~II > 21bums ~lue..9YaH phone il1 "Uh uh." fod1.0 8111! yovr order aI\:lVI'YI lid?" you C811 BWEGRASS STUDENT UNION THE MUSIC MAN RUSH ORDERS : 1 • 1 Call 1-502-267-9812 WHILE THEY LAST ... ~CEJ. All 8-Track tapes are 50% offthe advertised price CREDIT CARD PHONE ORDERS ORDER TODAY! OR SEND CHECK OR M.O. - TO: Bluegrass Records 3613 St. Edwards Drive Louisville, KY 40299 .----------------------------------------------- BLUEGRASS RECORDS NAME _ 3613 St. Edwards Drive STREET _ Louisville, Kentucky 40299 ClTy STATE ZlP _ INDICATE QUANTITY ALBUM CASSETTE 8-TRACK AFTER CLASS $7 $ THE OLDER ... THE BETTER $8 $ THE MUSIC MAN $9 $ POSTAGE $ .95 O~b~R DISCOUNT: $4 OFF When Purchasing a Set of All 3 Records or Tapes. DEDUCT DISCOUNT ENTER IF APPLICABLE - $ Canadian Orders Specify "U.S. Funds" TOTAL ENCLOSED $ ---------------------------------------- ------ The dl51rlbullon, sale or advertising 01 unofficial reco/dings Is not a IepresenlaHon thaI the contents 01 wch recordings ore oppropllate lor conlesl use. The ~,-CJ.1MmonizenEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 1984 VOL. XLIV No.5 C/A~:I.MONTHLY MAGAZINE PUBLISHED FOR AND ABOUT MEMBERS OF SPEBSQSA, INC., IN THE INTERESTS OF BARBERSHOP HARMONY. Features 6 CONVENTION HIGHLIGHTS 26 SAN ANTONIO SAYS HOWDY A review of the St. Louis Con FOR MID·WINTER vention - a week to remember. A big Texas welcome awaits Bar bershoppers heading for San An 12 THE WINNERS tonio in January. Sign up today! A photo album of the medalists, finalists, semi-finalists and quarter 30 ARE YOU SAVING YOUR SOUP finalists. -

San Antonio Past

Lockhill-Selma R V a n c e B J e d a v a 0123Mi c n k A d s t e F o s r r n e a e 10 1535 B d R R 01 2 34Km W e a d d d b r i R c c rt o k 87 e c s k k b Ca 16 c R u E r d g Ja R ck d 410 k k e e e e Huebner Rd r r Evers Rd Olmo C B C a Balcones h n Creek de c ra Heights n on R e r d Callaghan Rd F Le 471 West Ave West Rd 10 m k so e Fredericksburg R ris e G r 410 B Fr C a Hillcrest Dr nde r ra e 16 R n r d 3478 d b In D Hilde u g Quill Dr Culebra Rd ra m H w d e i v d St Cloud Rd a St Mary's W Woodlawn Ave o r allaghan R allaghan Univ B C Culebra Rd WOODLAWN LAK Culebra R PARK Potranco Rd Southwest Research Zarzamora Creek op 410 L Institute e SAN Lo on W C Commerce N re e d k Gen Clements ANTO Southwest Mc Mullen Dr Commerce Buena Vista St Foundation 151 o for Research Guadalupe St z 16 Bra & Education R allaghan Old Hwy 90 W 36th St Marbach Rd C To Seaword To 410 Castroville Rd 90 G Gro r wden Frio City Rd o Zarzamora St w Mc Mullen Dr d Lackland e n ts Cupples Rd n To El Paso El To Air Force Base e 353 m per d e l Kelly Billy Mitchell R C Dr Rd a Division n n e Valley Hi Truem Kelly ta G Air Force Base 13 Quin R Southcross B a e v y Medina Base Rd Military D A E r W l l is o Milita n Blvd Ray Ellison Blvd PEARSALL d Med PARK Bynum io R C d o I t l r n y e A d e w i o l r 35 k 410 a a erset R F n P Pearsall Rd n Cre om S o t n e Zarzamora St a k Ave Commercial New Laredo Hwy d r Hunter Blvd u eon o 16 L C J d r Am Expressway South e e k teet Pan o P erset RSW Loop 410 om 16 To Laredo S To Jourdanton B To Johnson N l ew a N ek Schertz