Amsterdam, Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geuzenveld-Slotermeer-Westpoort Voor U Ligt De Gebiedsagenda Van Geuzenveld-Slotermeer

Gemeente Gebiedsagenda Geuzenveld -Slotermeer -Westpoort Amsterdam 2016-2019 1. Gebiedsagenda Geuzenveld-Slotermeer-Westpoort Voor u ligt de gebiedsagenda van Geuzenveld-Slotermeer. De gebiedsagenda bevat de belangrijkste opgaven van het gebied op basis van de gebiedsanalyse, specifieke gebiedskennis en bestuurlijke ambities. Tijdens de Week van het Gebied en de daarop volgende Gebiedsbijeenkomst zijn bewoners, ondernemers en andere betrokkenen expliciet gevraagd om hun bijdrage te leveren aan deze agenda. De agenda belicht de ontwikkelopgave van het gebied voor de periode 2016-2019. Leeswijzer In paragraaf 2 wordt een samenvatting gegeven van deze gebiedsagenda. In paragraaf 3 wordt een beschrijving gegeven van het gebied. In paragraaf 4 wordt de opgave van het gebied uiteengezet door de belangrijkste cijfers uit de gebiedsanalyse te benoemen en inzicht te geven van wat is opgehaald bij bewoners, bedrijven en professionals uit het gebied. Tot slot wordt in deze paragraaf aangeven in hoeverre de opgave gekoppeld is aan de stedelijke prioriteiten uit het coalitieakkoord. In paragraaf 5 worden de prioriteiten van het gebied gepresenteerd. En in paragraaf 6 wordt uiteengezet welke stappen in het stadsdeel ondernomen zijn rond participatie met bewoners, ondernemers en andere betrokkenen uit de gebieden. 2. Samenvatting: Geuzenveld-Slotermeer-Westpoort Het gebied Geuzenveld-Slotermeer is een aantrekkelijk gebied voor (nieuwe) Amsterdammers vanwege de groene, rustige sfeer in de nabijheid van de grootstedelijke reuring. Er zijn relatief goedkope huur- en koopwoningen met veel licht, lucht en ruimte. Groengebieden als De Bretten, het Eendrachtspark, de Tuinen van West en de Sloterplas zijn belangrijke groene onderdelen van het gebied Geuzenveld-Slotermeer. Het bedrijventerrein Westpoort (Sloterdijken), onlangs verkozen tot het beste bedrijventerrein van Nederland, heeft de potentie zich te ontwikkelen tot de motor voor dit gebied als het gaat om wonen, werk en onderwijs. -

Thuiswonende Tot -Jarige Amsterdammers

[Geef tekst op] - Thuiswonende tot -jarige Amsterdammers Onderzoek, Informatie en Statistiek Onderzoek, Informatie en Statistiek | Thuiswonende tot - arigen in Amsterdam In opdracht van: stadsdeel 'uid Pro ectnummer: )*) Auteru: Lieselotte ,icknese -ester ,ooi ,ezoekadres: Oudezi ds .oorburgwal 0 Telefoon 1) Postbus 213, ) AR Amsterdam www.ois.amsterdam.nl l.bicknese6amsterdam.nl Amsterdam, augustus )* 7oto voorzi de: 8itzicht 9estertoren, fotograaf Cecile Obertop ()) Onderzoek, Informatie en Statistiek | Thuiswonende tot - arigen in Amsterdam Samenvatting Amsterdam telt begin )* 0.*2= inwoners met een leefti d tussen de en aar. .an hen staan er 03.0)3 ()%) ingeschreven op het woonadres van (een van) de ouders. -et merendeel van deze thuiswonenden is geboren in Amsterdam (3%). OIS heeft op verzoek van stadsdeel 'uid gekeken waar de thuiswonende Amsterdammers wonen en hoe deze groep is samengesteld. Ook wordt gekeken naar de kenmerken van de -plussers die hun ouderli ke woning recent hebben verlaten. Ruim een kwart van de thuiswonende tot -jarigen woont in ieuw-West .an de thuiswonende tot en met 0*- arige Amsterdammers wonen er *.=** (2%) in Nieuw- 9est. Daarna wonen de meesten in 'uidoost (2.)A )2% van alle thuiswonenden). De stadsdelen Noord en Oost tellen ieder circa 1.2 thuiswonenden ()1%). In 9est zi n het er circa 1. ()0%), 'uid telt er ruim .) ())%) en in Centrum gaat het om .) tot en met 0*- arigen (2%). In bi lage ) zi n ci fers opgenomen op wi k- en buurtniveau. Driekwart van alle thuiswonende tot en met 0*- arige Amsterdammers is onger dan 3 aar. In Nieuw-9est en Noord is dit aandeel wat hoger (==%), terwi l in 'uidoost thuiswonenden vaker ouder zi n dan 3 aar (0%). -

De Maasbode Verschijnt Dagelijks Des Ochtends En Des Avonds, Uitgezonderd Zon- Dagavond En Maandagochtend

72ste JAARGANG. No. 29071. VRIJDAG 2 FEBRUARI 1940 AVONDBLAD - VIER BLADEN De Maasbode verschijnt dagelijks des ochtends en des avonds, uitgezonderd Zon- dagavond en Maandagochtend. WENNEKER^ ■m SCHIEDAM Mm Abonnementsprijs voor geheel Nederland f 4.50 per kwartaal, f 1 50 per maand, f OJS per week. Losse nummers 9 cent Advertentiën 75 cent per regel. Handels- advertentiën 70 cent per regel Ingezonden Mededeelingen dubbel tarief. Liefdadigheids- advertentiën half tarief. Zaterdagavond en Zondagochtend 10 cent per regel verhooging. MAASBODE regels DE Kabouter-advertentiën groot 5 f 2.—. Uitgave van de NV. de Courant De Maasbode, Groote Markt 30. Rotterdam DAGBLAD VOOR NEDERLAND MET OCHTEND- EN AVOND-EDITIE. |ÜdË OUDE Telefoon 26200 11735. PROEVE? | Postbus 723 — — Giro Het dagblad „Proia", merkt naar aanlei- ding van de Balkan-ententeconferentie op, VOORNAAMSTE NIEUWS. dat de politieke atmosfeer vandaag er op 1 wijst, dat alle Donau- en Balkanstaten vriendschappelijk tegenover gestemd van Italië Melding wordt gemaakt van vier belang- Conferentie zijn. Belgrado rijke punten, op begonnen welke de heden conferentie te Belgrado zouden worden De petroleum-kwestie. aangesneden Pag. L LONDEN, 2 Februari (U.P.) De strtfd om Bij het indienen van de Japansche begroo» heden de Roemeensche petroleum zal betrekkelijk ting heeft de minister van financiën een geopend. de redevoering gehouden Paj}. 2. spoedig tot een einde komen, aldus mee- ning van vooraanstaande personen uit de wereld van de olie-industrie, zoowel als van Een nieuw Russisch offensief aan het front Te moeilijker wordt dit probleem, waar de vooraanstaande diplomaten. in Karelië is tot nu toe op den Finschen te- eene staat (Roemenië) onmiddellijk be- Donderdag vernamen wij uit betrouwbare genstand doodgeloopen Pag. -

Transvaalbuurt (Amsterdam) - Wikipedia

Transvaalbuurt (Amsterdam) - Wikipedia http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transvaalbuurt_(Amsterdam) 52° 21' 14" N 4° 55' 11"Archief E Philip Staal (http://toolserver.org/~geohack Transvaalbuurt (Amsterdam)/geohack.php?language=nl& params=52_21_14.19_N_4_55_11.49_E_scale:6250_type:landmark_region:NL& pagename=Transvaalbuurt_(Amsterdam)) Uit Wikipedia, de vrije encyclopedie De Transvaalbuurt is een buurt van het stadsdeel Oost van de Transvaalbuurt gemeente Amsterdam, onderdeel van de stad Amsterdam in de Nederlandse provincie Noord-Holland. De buurt ligt tussen de Wijk van Amsterdam Transvaalkade in het zuiden, de Wibautstraat in het westen, de spoorlijn tussen Amstelstation en Muiderpoortstation in het noorden en de Linnaeusstraat in het oosten. De buurt heeft een oppervlakte van 38 hectare, telt 4500 woningen en heeft bijna 10.000 inwoners.[1] Inhoud Kerngegevens 1 Oorsprong Gemeente Amsterdam 2 Naam Stadsdeel Oost 3 Statistiek Oppervlakte 38 ha 4 Bronnen Inwoners 10.000 5 Noten Oorsprong De Transvaalbuurt is in de jaren '10 en '20 van de 20e eeuw gebouwd als stadsuitbreidingswijk. Architect Berlage ontwierp het stratenplan: kromme en rechte straten afgewisseld met pleinen en plantsoenen. Veel van de arbeiderswoningen werden gebouwd in de stijl van de Amsterdamse School. Dit maakt dat dat deel van de buurt een eigen waarde heeft, met bijzondere hoekjes en mooie afwerkingen. Nadeel van deze bouw is dat een groot deel van de woningen relatief klein is. Aan de basis van de Transvaalbuurt stonden enkele woningbouwverenigingen, die er huizenblokken -

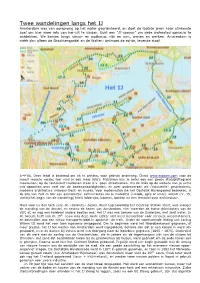

Twee Wandelingen Langs Het IJ

Twee wandelingen langs het IJ Amsterdam was van oorsprong op het water georiënteerd, en doet de laatste jaren haar stinkende best om hier weer iets van her-uit te vinden. Echt een “ IJ-opener” om deze waterstad opnieuw te ontdekken. We komen langs nieuw- en oudbouw, rijk en arm, wonen en werken. Amsterdam is méér dan alleen de Grachtengordel en de Wallen: ontmoet de echte, levende stad! 6-4-’06. Deze tekst is bestemd om uit te printen, voor gebruik onderweg. Check www.ecocam.com voor de meest recente versie; hier vind je ook meer foto’s. Misschien kan je beter ook een goede stadsplattegrond meenemen; op de routekaart hierboven staan b.v. geen straatnamen. Via de links op de website kan je extra info opzoeken over veel van de bezienswaardigheden, en over onderwerpen als (industriële) geschiedenis, moderne architectuur (Havens-Oost) en musea. Voor modernisten die het Oostelijk Havengebied bezoeken, is de site van Talk to Me! een aanradertje: cultuurroutes via je mobieltje (i-mode, gprs of umts). ARCAM (nr. 15, vlakbij het begin van de wandeling) heeft foldertjes, kaarten, boeken en een leestafel over architectuur. Maar voor nu dan toch even de –absolute– basics . Waar tegenwoordig het Centraal Station staat, was vroeger de monding van de Amstel, en tevens de haven van Amsterdam. Hier meerden de trotse driemasters van de VOC af, en nog een heleboel andere bootjes ook. Het IJ was een zeearm van de Zuiderzee, met zout water. In de tweede helft van de 19 de eeuw was deze route echter niet meer bevaarbaar voor serieuze oceaanstomers, en bovendien was een nieuw transportmiddel in opkomst: de trein. -

Bestemmingsplan Nieuwendam-Noord-Werengouw 24 November 2011

Bestemmingsplan Nieuwendam-Noord-Werengouw 24 november 2011 Bestemmingsplan Nieuwendam-Noord-Werengouw Stadsdeel Noord, Gemeente Amsterdam Toelichting 24 november 2011 1 Bestemmingsplan Nieuwendam-Noord-Werengouw Stadsdeel Noord, Gemeente Amsterdam Toelichting 24 november 2011 Inhoud Pagina 1. Inleiding 1 1.1 Aanleiding en doel 2 1.2 Begrenzing van het plangebied 2 1.3 Leeswijzer 3 2. Ruimtelijke structuur 4 2.1 Inleiding 4 2.2 Werengouw 5 2.3 Duinluststraat - Zandvoortstraat 8 2.4 Omgeving Naardermeerstaat 10 2.5 Omgeving Gooiluststraat / De Breekstraat 12 2.6 Zuiderzeepark 14 2.7 Woningen Beemsterstraat 17 2.8 Maatschappelijke voorzieningen 18 2.9 Water en groen 20 2.10 Verkeersstructuur 22 3 Nieuwe ontwikkelingen 24 3.1 Kompaslocatie 24 3.2 Park Groene Zoom 28 3.3 Duinpanlocatie 28 3.4 Theehuis 29 3.5 Duinlustschool 30 4. Plankader 31 4.1 Inleiding 31 4.2 Vigerende bestemmingsplannen 31 4.3 Europees beleid 33 4.4 Rijksbeleid 33 4.5 Provinciaal beleid 37 4.6 Hoogheemraadschap 39 4.7 Regionaal beleid 41 4.8 Gemeentelijk beleid 44 4.9 Stadsdeelbeleid 47 5. Milieu- en veiligheidsaspecten 54 5.1 Algemeen 54 5.2 Verkeer 54 5.3 Geluid 54 5.4 Luchtkwaliteit 57 5.5 Bodem 58 5.6 Externe veiligheid 59 5.7 Flora en fauna 62 5.8 Cultuurhistorie en archeologie 65 5.9 Luchthavenindelingbesluit 68 5.10 Kabels en leidingen 69 6. Water 70 7. Juridische planopzet 73 7.1 Opbouw van het bestemmingsplan 73 7.2 Verbeelding 73 7.3 Regels 74 7.4 Artikelsgewijze toelichting 75 2 Bestemmingsplan Nieuwendam-Noord-Werengouw Stadsdeel Noord, Gemeente Amsterdam Toelichting 24 november 2011 7.5 Handhaving 88 8. -

NDSM Werf Od Skvotera Do Kulturnih Poduzetnika

izdavač: savez udruga klubtura urednici: kruno jošt vesna janković ivana armanini karolina pavić lela vujanić pero gabuda tanja topolovec suradnici: andrija vranić darko Ijubičić helga paškvan denis pilepić bruno motik maja vujinović tomislav medak oleg drageljević denis kajić bojan žižović emina višnić design: tanja topolovec grafika: tanja topolovec saša ištok lektura martina majdak karolina pavić redakcija: http://tamtam.mi2.hr/casopis www.uke.hr/04 00385(0)48/682-837 e-mai1:[email protected] štampa Tipograf Zagreb naklada 1500 studeni 2004 ostvareno kroz savez udruga c lu b tu re CT www.clubture.org suradnja: CENTAR ZA MIROVNE STUDIJE ZG s PIRIT RI UDRUGA UKE KŽ Mi2 MEDIALAB ZG donator: GRADSKI URED ZA KULTURU GRADA RIJEKE GRADSKI URED ZA KULTURU GRADA ZAGREBA zahvaljujemo na pomoći: www.litkon.org književni klub booksa komikaze ruta lina 1 intervju/teo celakoski..4-6 mapiranje vaninstitucionalne scene u regiji..7 clubture putopis kvarnerom&istrom..8-19 rasprave o nezavisnoj kulturi..20 cd/trd...21 eutanazija nepodobnih..22-23 od skvotera do kulturnih poduzetnika..24-27 skvot report..28-29 foto/srđan kovačević..30-31 projekt krojcberg..32-35 strip/wostok..36-39 što je permakultura?..40-41 put bez povratka..42 akcija "za čišćenje plaže"..43 bakica vs. mesar na tragu aarhuske konvencije..44-45 sjesti na kavu i čitati bojkot..46-47 slobodno stvaralaštvo?!..47-48 dobre novine coding all day, A KAD POGLEDATE KIOSKE NA partying all night 49-50 ŽELJEZNIČKOJ STANICI GRADA ZAGREBA NE NAĐETE NI JEDAN shalombrothers..51-55 ČASOPIS KOJI BI PRELISTALI, the good news is: SAMO DILAN DOGA, KOJI JE you can change it;-)))...56-57 VEĆ I SAM OFUCAN. -

Gebiedsagenda Geuzenveld-Slotermeer- Westpoort Amsterdam 2016-2019

Gemeente Gebiedsagenda Geuzenveld-Slotermeer- Westpoort Amsterdam 2016-2019 1. Gebiedsagenda Geuzenveld-Slotermeer-Westpoort Voor u ligt de gebiedsagenda van Geuzenveld-Slotermeer. De gebiedsagenda bevat de belangrijkste opgaven van het gebied op basis van de gebiedsanalyse, specifieke gebiedskennis en bestuurlijke ambities. Tijdens de Week van het Gebied en de daarop volgende Gebiedsbijeenkomst zijn bewoners, ondernemers en andere betrokkenen expliciet gevraagd om hun bijdrage te leveren aan deze agenda. De agenda belicht de ontwikkelopgave van het gebied voor de periode 2016-2019. Leeswijzer In paragraaf 2 wordt een samenvatting gegeven van deze gebiedsagenda. In paragraaf 3 wordt een beschrijving gegeven van het gebied. In paragraaf 4 wordt de opgave van het gebied uiteengezet door de belangrijkste cijfers uit de gebiedsanalyse te benoemen en inzicht te geven van wat is opgehaald bij bewoners, bedrijven en professionals uit het gebied. Tot slot wordt in deze paragraaf aangeven in hoeverre de opgave gekoppeld is aan de stedelijke prioriteiten uit het coalitieakkoord. In paragraaf 5 worden de prioriteiten van het gebied gepresenteerd. En in paragraaf 6 wordt uiteengezet welke stappen in het stadsdeel ondernomen zijn rond participatie met bewoners, ondernemers en andere betrokkenen uit de gebieden. 2. Samenvatting: Geuzenveld-Slotermeer-Westpoort Het gebied Geuzenveld-Slotermeer is een aantrekkelijk gebied voor (nieuwe) Amsterdammers vanwege de groene, rustige sfeer in de nabijheid van de grootstedelijke reuring. Er zijn relatief goedkope huur- en koopwoningen met veel licht, lucht en ruimte. Groengebieden als De Bretten, het Eendrachtspark, de Tuinen van West en de Sloterplas zijn belangrijke groene onderdelen van het gebied Geuzenveld-Slotermeer. Het bedrijventerrein Westpoort (Sloterdijken), onlangs verkozen tot het beste bedrijventerrein van Nederland, heeft de potentie zich te ontwikkelen tot de motor voor dit gebied als het gaat om wonen, werk en onderwijs. -

A09 Oostelijke Eilanden / Kadijken Buurtenquête 2016 Stadsdeel Centrum

A09 Oostelijke Eilanden / Kadijken Buurtenquête 2016 Stadsdeel Centrum Onderzoek, Informatie en Statistiek Gemeente Amsterdam Onderzoek, Informatie en Statistiek Buurtenquête stadsdeel Centrum 2016, A09 Oostelijke Eilanden/Kadijken In opdracht van: Stadsdeel Centrum Projectnummer: 16111 Jessica Greven Esther Jakobs Laura de Graaff Willem Bosveld Patricia Jaspers Ivo de Bruijn Marieke Bakker Peter van Hinte Bart Karpe Aram Limpens Anouk Schrijver Bezoekadres: Oudezijds Voorburgwal 300 Telefoon 020 251 0462 Postbus 658, 1000 AR Amsterdam www.ois.amsterdam.nl [email protected] Amsterdam, mei 2016 Foto voorzijde: Uitzicht Westertoren, fotograaf Cecile Obertop (2014) 2 Gemeente Amsterdam Onderzoek, Informatie en Statistiek Buurtenquête stadsdeel Centrum 2016, A09 Oostelijke Eilanden/Kadijken Inhoud Inleiding 5 Resultaten 8 1.1 Profiel van de deelnemers 8 1.2 Algemeen 9 1.2.1 Meest favoriete plek in de buurt 9 1.2.2 Wat de gemeente als eerste aan zou moeten pakken in de buurt 10 1.3 Verkeer 10 1.3.1 Vervoermiddelen 10 1.3.2 Onveilige verkeerssituaties in de buurt 11 1.3.3 Grootste fietsparkeerprobleem in de buurt 12 1.3.4 Gevaarlijke verkeerssituaties voor fietsers in de buurt 13 1.4 Behoud van kwaliteit en optimaal gebruik van de openbare ruimte 15 1.4.1 Belemmerde doorgang 16 1.4.2 Parkeermaatregelen 17 1.5 Bewaken en verbeteren van de functiebalans (wonen, werken en recreëren) 18 1.5.1 Uitgaan 18 1.5.2 Balans tussen wonen, werken en recreëren in de buurt 18 1.5.3 Verhuisplannen 19 1.6 Bewaken en verbeteren van de leefbaarheid 20 1.6.1 -

Covid-19 Circular Recovery and Resilience Action Plan Pakhuis De Zwijger

COVID-19 CIRCULAR RECOVERY AND RESILIENCE ACTION PLAN PAKHUIS DE ZWIJGER --------------------- 12 March 2021 by Thomas van de Sandt This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 776758 1 COVID-19 CIRCULAR RECOVERY AND RESILIENCE ACTION PLAN PAKHUIS DE ZWIJGER --------------------- 12 March 2021 by Thomas van de Sandt 2 CONTENTS PREFACE 4 1. INTRODUCTION AND CONTEXT 5 1.1. ADAPTIVE REUSE OF PAKHUIS DE ZWIJGER 5 1.2. ORGANISATION AND BUSINESS MODEL 7 1.3. PARTNERS 8 1.4 DESCRIPTION OF THE HIP-PROCESS 8 2. ANALYSIS & LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE HIP PROCESS 10 2.1. ASSETS AND CHALLENGES 10 2.2. IMPACT COVID-19 ON THE BUSINESS MODEL 10 2.3. INTERNAL PRACTICES ON CIRCULARITY 11 2.4. LOCAL STAKEHOLDERS ON CIRCULAR ADAPTIVE REUSE OF CULTURAL HERITAGE 12 3. MOVING FORWARD: A FOCUS ON RECOVERY AND RESILIENCE 14 3.1. PRIORITY AREAS FOR ACTION 14 3.2. RESTRUCTURING GOVERNANCE 14 3.3. RESILIENT BUSINESS MODEL 15 3.4. NEW AMBITIONS 16 3.5. CIRCULAR BUSINESS PRACTICES 16 4. MONITORING AND EVALUATION 17 3 PREFACE Pakhuis de Zwijger is a unique example of the It has been interesting to work on the European adaptive reuse of cultural heritage, combining Union’s Horizon 2020 “Circular models Leveraging an approachable (free) public programming Investments in Cultural heritage adaptive reuse” in a national monument with a successful (CLIC) project during this period. Amsterdam was one commercial business model. In 2020, however, of four pilots within CLIC (together with Salerno city, this has all been put to the test. -

40 | P a G E Vehicle Routing Models & Applications

INFORMS TSL First Triennial Conference July 26-29, 2017 Chicago, Illinois, USA Vehicle Routing Models & Applications TA3: EV Charging Logistics Thursday 8:30 – 10:30 AM Session Chair: Halit Uster 8:30 Locating Refueling Points on Lines and Comb-Trees Pitu Mirchandani, Yazhu Song* Arizona State University 9:00 Modeling Electric Vehicle Charging Demand 1Guus Berkelmans, 1Wouter Berkelmans, 2Nanda Piersma, 1Rob van der Mei, 1Elenna Dugundji* 1CWI, 2HvA 9:30 Electric Vehicle Routing with Uncertain Charging Station Availability & Dynamic Decision Making 1Nicholas Kullman*, 2Justin Goodson, 1Jorge Mendoza 1Polytech Tours, 2Saint Louis University 10:00 Network Design for In-Motion Wireless Charging of Electric Vehicles in Urban Traffic Networks Mamdouh Mubarak*, Halit Uster, Khaled Abdelghany, Mohammad Khodayar Southern Methodist University 40 | Page Locating Refueling Points on Lines and Comb-trees Pitu Mirchandani School of Computing, Informatics and Decision Systems Engineering, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona 85281 United States Email: [email protected] Yazhu Song School of Computing, Informatics and Decision Systems Engineering, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona 85281 United States Email: [email protected] Due to environmental and geopolitical reasons, many countries are embracing electric vehicles as an alternative to gasoline powered automobiles. There are other alternative fuels such as Compressed Gas and Hydrogen Fuel Cells that have also been tested for replacing gasoline powered vehicles. However, since the associated refueling infrastructure of alternative fuel vehicles is sparse and is gradually being built, the distance between refueling points becomes a crucial attribute in attracting drivers to use such vehicles. Optimally locating refueling points (RPs) will both increase demand and help in developing a refueling infrastructure. -

From Squatting to Tactical Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2019 Between the Cracks: From Squatting to Tactical Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993 Amanda S. Wasielewski The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3125 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] BETWEEN THE CRACKS: FROM SQUATTING TO TACTICAL MEDIA ART IN THE NETHERLANDS, 1979–1993 by AMANDA WASIELEWSKI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partiaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of PhiLosophy, The City University of New York 2019 © 2019 AMANDA WASIELEWSKI ALL Rights Reserved ii Between the Cracks: From Squatting to TacticaL Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993 by Amanda WasieLewski This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of PhiLosophy. Date David JoseLit Chair of Examining Committee Date RacheL Kousser Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Marta Gutman Lev Manovich Marga van MecheLen THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Between the Cracks: From Squatting to TacticaL Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993 by Amanda WasieLewski Advisor: David JoseLit In the early 1980s, Amsterdam was a battLeground. During this time, conflicts between squatters, property owners, and the police frequentLy escaLated into fulL-scaLe riots.