The Association Between Education and Induced Abortion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Safety and Quality of Abortion Care in the United States (2018)

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://nap.edu/24950 SHARE The Safety and Quality of Abortion Care in the United States (2018) DETAILS 222 pages | 6 x 9 | PAPERBACK ISBN 978-0-309-46818-3 | DOI 10.17226/24950 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK Committee on Reproductive Health Services: Assessing the Safety and Quality of Abortion Care in the U.S.; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Board on Health Care Services; Health and Medicine Division; National FIND RELATED TITLES Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine SUGGESTED CITATION National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2018. The Safety and Quality of Abortion Care in the United States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24950. Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. The Safety and Quality of Abortion Care in the United States THE SAFETY AND QUALITY OF ABORTION CARE IN THE UNITED STATES Committee on Reproductive Health Services: Assessing the Safety and Quality of Abortion Care in the U.S. Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice Board on Health Care Services Health and Medicine Division A Consensus Study Report of Copyright National Academy of Sciences. -

A Reproductive Right, Or a Moral Profligacy?

A REPRODUCTIVE RIGHT, OR A MORAL PROFLIGACY? A POLICY PAPER DISCUSSING THE LEGISLATIVE FUTURE FOR MALTA An Għaqda Studenti Tal-Liġi Policy Paper © Għaqda Studenti tal-Liġi 2020 OPENING REMARKS INTRODUCTION It is with great pleasure that I present A multidisciplinary modus operandi was to you this year’s GħSL policy paper employed to offer a holistic discussion addressing the subject of Abortion, a and this was achieved through a paper which is the culmination of the thorough examination of pertinent comprehensive work of the GħSL Policy areas beyond the legal sphere such as Office. medical research, ethical considerations involved, as well as the psychological GħSL strives to keep law students as aspects, among others. well as society as a whole abreast regarding current legal issues in Malta. Moreover, a comparative exercise was An ongoing area of contention featuring carried out, whereby the laws regulating, across local media centres around the restricting and prohibiting abortion were topic of abortion. Due to the polarised evaluated. This contributed towards a views on this subject, the GħSL comprehensive outcome of this policy Executive Board decided that it would paper and provided a robust reference be opportune to delve into this topic. point for active and potential students alike. As a body representing the interests of law students, throughout this paper our Finally, I would like to thank the main focus was to maintain and uphold colleagues of GħSL, including all those an impartial appreciation of the law who contributed to this paper, namely while taking into account the sensitive Dr Desiree Attard, Andrew Sciberras, nature of this topic. -

Noetic Propaedeutic Pedagogy As a Panacea to the Problem of Abortion Peter B

Online Journal of Health Ethics Volume 12 | Issue 1 Article 4 Noetic Propaedeutic Pedagogy as a Panacea to the Problem of Abortion Peter B. Bisong [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://aquila.usm.edu/ojhe Part of the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Bisong, P. B. (2016). Noetic Propaedeutic Pedagogy as a Panacea to the Problem of Abortion. Online Journal of Health Ethics, 12(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.18785/ojhe.1201.04 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Online Journal of Health Ethics by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Noetic Propaedeutic Pedagogy as a Panacea to the Problem of Abortion Introduction Abortion has over the years posed ethical, medical, political and legal problems in the world and in Nigeria in particular. These problems (such as, danger to health, psychological trauma, unnecessary economic cost, population depletion etc) have been and have continued to be fuelled by the pro-abortionists supportive arguments. The pro-abortionists argue that abortion is good because it brings financial benefits to medical practitioners; it preserves the life of the mother when in danger; it controls population and enables the couple to live a more comfortable and meaningful life amongst other reasons. Unfortunately these arguments seem to have taken root in the heart of Nigerians, for only this will explain why Nigerians still perform abortion en masse in spite of the current illegality status of it. -

Yes We Can! Successful Examples of Disallowing ‘Conscientious Objection’ in Reproductive Health Care

The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care ISSN: 1362-5187 (Print) 1473-0782 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/iejc20 Yes we can! Successful examples of disallowing ‘conscientious objection’ in reproductive health care Christian Fiala, Kristina Gemzell Danielsson, Oskari Heikinheimo, Jens A. Guðmundsson & Joyce Arthur To cite this article: Christian Fiala, Kristina Gemzell Danielsson, Oskari Heikinheimo, Jens A. Guðmundsson & Joyce Arthur (2016) Yes we can! Successful examples of disallowing ‘conscientious objection’ in reproductive health care, The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care, 21:3, 201-206, DOI: 10.3109/13625187.2016.1138458 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/13625187.2016.1138458 Published online: 03 Feb 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 374 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=iejc20 Download by: [81.223.16.2] Date: 28 October 2016, At: 06:29 THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF CONTRACEPTION AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH CARE, 2016 VOL. 21, NO. 3, 201–206 http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/13625187.2016.1138458 SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC ARTICLE Yes we can! Successful examples of disallowing ‘conscientious objection’ in reproductive health care Christian Fialaa,b, Kristina Gemzell Danielssonb, Oskari Heikinheimoc, Jens A. Guômundssond and Joyce Arthure aGynmed Clinic for Abortion and Family -

TOP 10 MYTHS ABOUT ABORTION by Ingrid Skop, M.D

Cover TOP 10 MYTHS ABOUT ABORTION By Ingrid Skop, M.D. family research council Washington, D.C. A NOTE FROM THE AUTHOR: I hope the points I have raised in this paper will cause those who consider themselves to be “pro-choice” to question some of the assumptions they have made about abortion. Abortion is a difficult topic to talk or even think about. It has invaded deeply into the fiber of our society precisely because most of us do not want to address it until it confronts us directly. While most Americans have ignored it and while our health departments and medical societies have turned a blind eye to it, abortion has adversely affected far too many women, injured many physically and emotionally, destroyed families, and damaged the psyche of our country. Pro-abortion rhetoric sounds so benign (“women’s rights”; “reproductive freedom”; “women’s health care”) that many times we fail to think about what these terms represent. You don’t have to believe like I do—that abortion is harmful to women, families, and society. But please have the courage to look into it yourself. Follow the leads I have provided in the citations to study this subject more deeply. Begin to have difficult conversations with friends and family so you can help others to really confront this issue too. It is time that our country sees abortion for what it really is—for the sake of women and children yet unborn. Ingrid Skop, M.D. April 23, 2018 Ingrid Skop, M.D., F.A.C.O.G. -

Abortion Policies and Reproductive Health Around the World

Abortion Policies and Reproductive Health around the World United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division DESA The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environmental data and information on which States Members of the United Nations draw to review common problems and take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint courses of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises interested Governments on the ways and means of translating policy frameworks developed in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. Notes The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This report presents data for countries using a traditional classification by development group. The “developed regions” comprise all countries and areas of Europe plus Northern America, Australia, New Zealand and Japan. The “developing regions” comprise all countries and areas of Africa, Asia (excluding Japan), Latin America and the Caribbean plus Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia. -

Abortion and Repeat Abortion in Grampian

Abortion and Repeat Abortion In Grampian A report for the Sexual Health and Blood Borne Virus Managed Care Network (MCN) NHS Grampian March 2015 This document is also available in large print and other formats and languages upon request. Please call NHS Grampian Corporate Communications on (01224) 551116 or (01224) 552245. Contents Page Acknowledgements 1 Glossary 2 Foreword 3 Recommendations 4 Introduction 5 Section 1: Abortions in Grampian (2009-2013) 6 1. Background 6 2. Overview of abortion rates in Grampian: ISD Data 6 2.1 Grounds for abortion 7 2.2 Abortion rates and deprivation 8 3. Abortion rates by age and local authority area 9 3.1 Aberdeen City 9 3.2 Aberdeenshire 9 3.3 Moray 11 4. Abortion rates by intermediate zone 11 4.1 Aberdeen City 11 4.2 Aberdeenshire 12 4.3 Moray 13 5. Abortion rates by deprivation 15 5.1 Aberdeen City 15 5.2 Aberdeenshire 15 5.3 Moray 15 6. Abortion rates by GP cluster zone 17 6.1 Aberdeen 17 6.2 Aberdeenshire 17 6.3 Moray 17 7. Travel times to Aberdeen Royal Infirmary and Dr Grays 19 8. Key Findings 22 Section 2: Repeat abortions in Grampian (2010-2013) 23 1. Background 23 2. Results: Analysis of the Grampian TOP Database 23 2.1 Comparison of characteristics of women with 24 single and multiple abortions 2.2 Multivariate analysis 24 Section 3: International Systematic Review – Determinant 29 factors of repeat abortion 1. Background 29 1.1 Definitions 30 2. Systematic review 30 2.1 Systematic review methods 30 2.2 Scope of the review 30 2.3 Search strategy 31 2.4 Inclusion Criteria 31 2.5 Exclusion Criteria 31 2.6 Data extraction and assessment for study inclusion 31 3. -

Induced Abortion and Mental Health

INDUCED ABORTION AND MENTAL HEALTH A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF THE MENTAL HEALTH OUTCOMES OF INDUCED ABORTION, INCLUDING THEIR PREVALENCE AND ASSOCIATED FACTORS. DECEMBER 2011 Developed for the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges by National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, London, 2011 This review was funded by the Department of Health The National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH) was established in 2001 at the Royal College of Psychiatrists, in partnership with the British Psychological Society. Its primary role is to develop evidence-based mental health reviews and clinical guidelines CONTENTS Steering Group Members................................................,............................................................................................05 Executive summary.......................................................................................................................................................07 1 Introduction.........................................................................................................................................................09 1.1 Background...........................................................................................................................................................................09 1.2 Terminology...........................................................................................................................................................................11 1.3 Abortion Legislation..............................................................................................................................................................11 -

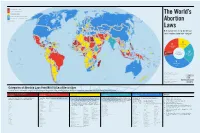

World-Abortion-Map.Pdf

I PROHIBITED ALTOGETHER II TO SAVE THE WOMAN’S LIFE III TO PRESERVE HEALTH GREENLAND The World’s IV BROAD SOCIAL OR ECONOMIC GROUNDS FINLAND V ON REQUEST (GESTATIONAL LIMITS VARY) ICELAND SWEDEN RUSSIAN FEDERATION UNKNOWN CANADA NORWAY Abortion ESTONIA LATVIA NORTHERN IRELAND DENMARK LITHUANIA NETHERLANDS IRELAND GREAT BELARUS BRITAIN GERMANY POLAND BELGIUM CZECH LUXEMBOURG UKRAINE REPUBLIC KAZAKHSTAN SLOVAK REP. MONGOLIA LIECHTENSTEIN AUSTRIA Laws SWITZERLAND HUNGARY MOLDOVA SLOVENIA FRANCE CROATIA ROMANIA ITALY SAN BOSNIA SERBIA MONACO MARINO HERZ. DEM. PEOPLE’S MONTENEGRO BULGARIA UNITED STATES ANDORRA KOSOVO GEORGIA UZBEKISTAN KYRGYZSTAN REP. OF KOREA How many women of reproductive age N. MACEDONIA PORTUGAL ALBANIA ARMENIA AZERBAIJAN SPAIN TURKMENISTAN REP. OF JAPAN TURKEY TAJIKISTAN KOREA live in countries under each category? CHINA MALTA GREECE CYPRUS SYRIA LEBANON AFGHANISTAN WEST BANK/GAZA STRIP MOROCCO TUNISIA IRAN ISRAEL IRAQ JORDAN KUWAIT NEPAL PAKISTAN BHUTAN BAHAMAS ALGERIA LIBYA QATAR MEXICO EGYPT BAHRAIN CUBA WEST SAUDI ARABIA BANGLADESH TAIWAN SAHARA UAE INDIA HONG KONG OMAN MYANMAR DOMINICAN REPUBLIC LAOS SAINT KITTS AND NEVIS MAURITANIA III BELIZE HAITI MALI JAMAICA PUERTO ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA NIGER RICO SUDAN THAILAND PHILIPPINES HONDURAS DOMINICA CAPE VERDE II 237 MILLION ERITREA YEMEN GUATEMALA SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES CHAD NICARAGUA SAINT LUCIA SENEGAL EL SALVADOR ARUBA BARBADOS GAMBIA CAMBODIA 359 MILLION 14% CURAÇAO BURKINA GRENADA GUINEA-BISSAU FASO DJIBOUTI VIETNAM COSTA RICA PANAMA TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO GUINEA BENIN MARSHALL ISLANDS 22% MICRONESIA NIGERIA SOMALIA SRI LANKA VENEZUELA ETHIOPIA SIERRA LEONE COTE TOGO CENTRAL D’IVOIRE SOUTH PALAU SURINAME GHANA AFRICAN SUDAN BRUNEI DARUSSALAM GUYANA LIBERIA REP. CAMEROON MALAYSIA COLOMBIA KIRIBATI MALDIVES EQUATORIAL GUINEA UGANDA SINGAPORE WOMEN OF SAO TOME AND PRINCIPE 90 MILLION IV DEM. -

Scientific Developments Relating to the Abortion Act 1967

House of Commons Science and Technology Committee Scientific Developments Relating to the Abortion Act 1967 Twelfth Report of Session 2006–07 Volume I HC 1045-I House of Commons Science and Technology Committee Scientific Developments Relating to the Abortion Act 1967 Twelfth Report of Session 2006–07 Volume I Report, together with formal minutes Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 29 October 2007 To be published by TSO on 6 November 2007 as HC 1045-I The Science and Technology Committee The Science and Technology Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Office of Science and Innovation and its associated public bodies. Current membership Mr Phil Willis MP (Liberal Democrat, Harrogate and Knaresborough) (Chairman) Adam Afriyie MP (Conservative, Windsor) Mrs Nadine Dorries MP (Conservative, Mid Bedfordshire) Mr Robert Flello MP (Labour, Stoke-on-Trent South) Linda Gilroy MP (Labour, Plymouth Sutton) Dr Evan Harris MP (Liberal Democrat, Oxford West & Abingdon) Dr Brian Iddon MP (Labour, Bolton South East) Chris Mole MP (Labour/Co-op, Ipswich) Dr Bob Spink MP (Conservative, Castle Point) Graham Stringer MP (Labour, Manchester, Blackley) Dr Desmond Turner MP (Labour, Brighton Kemptown) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental Select Committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No.152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at www.parliament.uk/s&tcom A list of Reports from the Committee in this Parliament is included at the back of this volume. -

Submissions to the Secondary Legislation Scrutiny Committee on the Abortion (Northern Ireland) (No

Submissions to the Secondary Legislation Scrutiny Committee on the Abortion (Northern Ireland) (No. 2) Regulations 2020 (SI 2020/503) Lord Alton of Liverpool Page 2 Both Lives Matter Page 6 Lord Brennan QC Page 9 Fiona Bruce MP Page 14 Joanne Bunting CO Page 17 CARE Northern Ireland Page 21 Catholic Bishops of Northern Ireland Page 24 Christian Medical Fellowship Page 27 The Rt Hon. Sir Jeffrey Donaldson MP Page 30 Don’t Screen Us Out Page 32 Paul Givan MLA Page 36 The Rt Hon. Sir John Hayes MP Page 41 The Rt Hon. Sir Edward Leigh MP Page 44 Ian Leist QC Page 47 Carla Lockhart MP Page 51 Dr Calum Miller Page 57 Lord Morrow Page 64 Carol Nolan TD and Senator Rónán Mullen Page 67 NI Voiceless Page 70 Baroness O’Loan Page 73 Presbyterian Church in Ireland Page 76 Right to Life Page 79 1 Lord Alton of Liverpool This submission concerns the Abortion (Northern Ireland) (No. 2) Regulations 2020, laid before Parliament on the 13th May. The points I raise are relevant to the Committee’s terms of reference: 4 (a) ‘that it is politically or legally important or gives rise to issues of public policy likely to be of interest to the House’ because the regulations introduces new forms of discrimination in Northern Ireland; and 4 (d) that ‘it may imperfectly achieve its policy objectives’ because the regulations promote discrimination. Many of the points I make reiterate those made in my submission to you concerning the earlier Abortion (Northern Ireland) Regulations 2020 because these new Regulations replicate the former in most respects. -

Abortion Safety: at Home and Abroad

Abortion Safety: At Home and Abroad Ingrid Skop, M.D.* ABSTRACT: In the U.S., legal abortion is considered extremely safe, and abortion-related mortality is reported to be far lower than mortality asso- ciated with term childbirth. Yet, the voluntary nature of abortion compli- cation reporting and ideological selection biases obscure the poor quality of the data used to support these assumptions. Worldwide, the World Health Organization reports that illegal abor- tion is extremely unsafe, killing and injuring vast numbers of women year- ly. They advocate for the liberalization of abortion laws so that women can access safer abortions. Yet, their calculations are based largely on subjec- tive opinions from a limited number of health care providers, with little objective verification from external sources. The limitations in the data should prompt calls for improved studies and more objective estimates of complications and deaths resulting from abortion, both legal and illegal. “Abortion is safer than childbirth.” “Legal abortion is extremely safe, and illegal abortion is extremely dangerous.” These assumptions drove the widespread legalization of abortion in the United States in 1973, and they continue to drive the effort to overturn all legislative safety restrictions on the procedure within our country, and to liberalize abortion laws internationally today. But are these assumptions true? How Could Pregnancy Pose a Risk to a Woman? During pregnancy, dramatic anatomical, physiological and biochemical changes occur in every organ of a woman’s body. Pregnancy-related hormones cause changes in metabolism, stress response, immune action, electrolyte balance and even neuro- logic function. Growth of the uterus causes a shift in position of intra-abdominal and * Partner of Northeast OB/GYN Associates; M.D., Washington University School of Medicine, St.