Downloaded From: Usage Rights: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Deriva- Tive Works 4.0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Webcare Is Vakkundig(Er) & Vanzelfsprekend Geworden'

‘Webcare is vakkundig(er) & vanzelfsprekend geworden’ Derde editie, april 2015 Arne Keuning Marco Derksen Mike Kelders Voorwoord Stand van Webcare 2015 Webcare werd in 2013 al vanzelfsprekend(er) gevonden. In 2015 kunnen Langs deze weg willen wij vooral we spreken dat er nu ook actief door organisaties wordt opgeroepen tot alle respondenten bedanken voor het stellen van vragen via sociale kanalen. Niet alleen de consument hun input. Zonder deze input was vindt het vanzelfsprekend, ook vele organisaties zijn zich bewust van de een goed beeld van webcare bij mogelijkheden van webcare en kiezen hier ook voor. Nederlandse organisaties niet mogelijk geweest. Ook dank aan ieder die zijn of haar netwerk heeft Webcare is gegroeid in belang en voor sommige grotere organisaties ook gevraagd mee te doen. Top! in volume. Reden genoeg om webcare structureel in je organisatie te be- leggen en verwachtingen over openings- en responstijden goed te mana- Arnhem, 20 april 2015 gen. Hierbij is het ook van belang om goed na te denken wat de Marco Derksen, Mike Kelders & mogelijke reactie strategieën zijn voor ‘hoe, wanneer en met welke toon’ Arne Keuning te reageren. Na een Quick Scan in 2012 is in september 2013 het eerste onderzoek naar de Stand van Webcare in Nederland gedaan. Dit onderzoek is een vervolg en uitbreiding daarop en onderzoekt hoe Nederlandse organisa- ties in 2015 aan webcare doen en welke effecten zij verwachten. Via e-mail, twitter en persoonlijke verzoeken werden (zoveel mogelijk Wij horen graag je mening, feed- praktiserende webcare-)medewerkers van organisaties gevraagd om aan back en aanvullingen op dit te geven hoe webcare in hun organisatie is georganiseerd en welke effec- onderzoeksrapport. -

Virtual Enrichment Ideas

CACFP At-Risk Afterschool Meals Enrichment Week 1 Date Activities ● National Geographic: Weird Nature Quiz. Go to the webpage and take the quiz to learn about weird things in nature. (science) https://kids.nationalgeographic.com/games/quizzes/quiz- whiz-weird-nature/ ● Check out art at one of the most famous museums in the world, the “MET” or Metropolitan Museum of Art. Go to the time machine webpage here: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/online-features/metkids/time-machine Click on “Africa,” then click “PUSH.” Click on the pieces of art one at a time and go through the experiences in the right column (like listen, watch, discover, etc.). (art, history) ● Learn how to make a time capsule! Go to the webpage. (various subjects) https://family.gonoodle.com/activities/how-to-make-a-time-capsule ● Inventions by Kids! Seed Launching Backpack. Go to the webpage and watch the video. (science, tech) https://thekidshouldseethis.com/post/seed-launching-backpack-a-3d-printed- pollinator-friendly-invention ● Bone Strength video from NFL. Go to the webpage to learn how to increase bone strength through nutrition and exercise! (science, phys ed) https://family.gonoodle.com/activities/bone- strength ● Watch live footage of African Animals. Go to the webpage and click on “African Wildlife.” Write a list of animals you see, or draw them. (science, social studies) https://explore.org/livecams ● Storyline Online- Oh the Places You’ll Go, read by Michelle Obama. Go to the webpage and read along or listen to the book. (language arts) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nVpHc8wsRKE ● Kennedy Center: World of Music. -

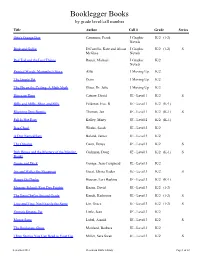

Booklegger Books by Grade Level/Call Number

Booklegger Books by grade level/call number Title Author Call # Grade Series Otto's Orange Day Cammuso, Frank J Graphic K/2 (1-2) Novels Bink and Gollie DiCamillo, Kate and Alison J Graphic K/2 (1-2) S McGhee Novels Red Ted and the Lost Things Rosen, Michael J Graphic K/2 Novels Painted Words: Marianthe's Story Aliki J Moving Up K/2 The Empty Pot Demi J Moving Up K/2 The Fly on the Ceiling: A Math Myth Glass, Dr. Julie J Moving Up K/2 Dinosaur Hunt Catrow, David JE - Level 1 K/2 S Billy and Milly, Short and Silly Feldman, Eve. B JE - Level 1 K/2 (K-1) Rhyming Dust Bunnie Thomas, Jan JE - Level 1 K/2 (K-1) S Fall Is Not Easy Kelley, Marty JE - Level 2 K/2 (K-1) Baa-Choo! Weeks, Sarah JE - Level 2 K/2 A Dog Named Sam Boland, Janice JE - Level 3 K/2 The Octopus Cazet, Denys JE - Level 3 K/2 S Dirk Bones and the Mystery of the Missing Cushman, Doug JE - Level 3 K/2 (K-1) S Books Goose and Duck George, Jean Craighead JE - Level 3 K/2 Iris and Walter the Sleepover Guest, Elissa Haden JE - Level 3 K/2 S Happy Go Ducky Houran, Lori Haskins JE - Level 3 K/2 (K-1) Monster School: First Day Frights Keane, David JE - Level 3 K/2 (1-2) The Best Chef in Second Grade Kenah, Katherine JE - Level 3 K/2 (1-2) S Ling and Ting: Not Exactly the Same Lin, Grace JE - Level 3 K/2 (1-2) S Emma's Strange Pet Little, Jean JE - Level 3 K/2 Mouse Soup Lobel, Arnold JE - Level 3 K/2 S The Bookstore Ghost Maitland, Barbara JE - Level 3 K/2 Three Stories You Can Read to Your Cat Miller, Sara Swan JE - Level 3 K/2 S September 2013 Pleasanton Public Library Page 1 of -

Final A1 8-806

www.tooeletranscript.com TUESDAY TOOELETRANSCRIPT Benson Grist Mill the perfect backdrop for beloved American musical. ULLETIN See B1 B August 8, 2006 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL. 113 NO. 21 50 cents Four child Aye! ‘Pirates’ film crew spied on Flats sex abuse by Jesse Fruhwirth STAFF WRITER There are no plans to change “Pirates of the cases hit Caribbean” to “Pirates of the West Desert.” Nonetheless, The Tooele local court Transcript- B u l l e t i n EDITOR’S NOTE: The contents of has con- this story may be offensive to some firmed that readers. J o h n n y by Jesse Fruhwirth Depp and STAFF WRITER the crew of Several unrelated but dreadful the block- charges of sex crimes against buster film children are making their way franchise photo/ Disney Enterprise Inc. through the court system in were at the Tooele. Second only to drug Bonneville Johhny Depp in “Dead’s Man Chest” charges, sex crimes against chil- Salt Flats dren account for a large share of Friday film- first-degree felonies on the court ing a scene for the upcoming calendar. third installment. The most recent charge filed Utah Gov. Jon Huntsman is against 21-year-old Tanisha had a secret lunch at the Salt Magness who faces a first-degree Flats Friday. He met with the felony charge of rape of a child. cast and crew of the next Magness made her initial appear- installment of “The Pirates of ance in court Monday, July 31. the Caribbean” series, which She was released on her own wrapped a one-day filming recognizance, but ordered to stay engagement near Wendover. -

Brown Bear Books Books Books Books

WINDMILL BOOKS WINDMILL BOOKS WINDMILL WINDMILL BROWN BEAR WINDMILL BROWN BEAR BOOKS BOOKS BOOKS BOOKS Ashley Brown Chairman [email protected] Ashley Brown Chairman [email protected] Anne O’Daly Children’s Publisher [email protected] 2018 BROWN Anne O’Daly Children’s Publisher [email protected] 2018 BROWN Lindsey Lowe Editorial Director [email protected] Lindsey Lowe Editorial Director [email protected] Audrey Curl Marketing and Rights [email protected] Audrey Curl Marketing and Rights [email protected] Unit 1/D Leroy House BEAR WINDMILL Unit 1/D Leroy House BEAR WINDMILL 436 Essex Road 436 Essex Road London N1 3PQ London N1 3PQ B B United Kingdom BEAR BOOKS ROWN BOOKS BOOKS United Kingdom BEAR BOOKS ROWN BOOKS BOOKS Tel: +44 (0)20 3176 8603 Tel: +44 (0)20 3176 8603 www.windmillbooks.co.uk www.windmillbooks.co.uk www.brownbearbooks.co.uk www.brownbearbooks.co.uk 2018 2018 WB_CAT18_COV_4.5_spine_final.indd 1 09/03/2018 18:17 WB_CAT18_COV_4.5_spine_final.indd 1 09/03/2018 18:17 CONTENTS Frontlist ..................................................................................................................... 2 UK Trade Titles ........................................................................................................ 20 Fast Track ................................................................................................................ 26 Facts at your Fingertips ........................................................................................ -

Wednesday, March 18, 2020 2:30 Pm

1 Wednesday, March 18, 2020 2:30 p.m. - 3:15 p.m. Pre-Opening Refreshment Ballroom Foyer ********** Wednesday, March 18, 2020 3:30 p.m. - 4:15 p.m. Opening Ceremony Ballroom Host: Jeri Zulli, Conference Director Welcome from the President: Dale Knickerbocker Guest of Honor Reading: Jeff VanderMeer Ballroom “DEAD ALIVE: Astronauts versus Hummingbirds versus Giant Marmots” Host: Benjamin J. Robertson University of Colorado, Boulder ********** Wednesday, March 18, 2020 4:30 p.m. - 6:00 p.m. 1. (GaH) Cosmic Horror, Existential Dread, and the Limits of Mortality Belle Isle Chair: Jude Wright Peru State College Dead Cthulhu Waits Dreaming of Corn in June: Intersections Between Folk Horror and Cosmic Horror Doug Ford State College of Florida The Immortal Existential Crisis Illuminates The Monstrous Human in Glen Duncan's The Last Werewolf Jordan Moran State College of Florida Hell . With a Beach: Christian Horror in Michael Bishop's "The Door Gunner" Joe Sanders Shadetree Scholar 2 2. (CYA/FTV) Superhero Surprise! Gender Constructions in Marvel, SpecFic, and DC Captiva A Chair: Emily Midkiff Northeastern State University "Every Woman Has a Crazy Side"? The Young Adult and Middle Grade Feminist Reclamation of Harley Quinn Anastasia Salter University of Central Florida An Elaborate Contraption: Pervasive Games as Mechanisms of Control in Ernest Cline's Ready Player One Jack Murray University of Central Florida 3. (FTFN/CYA) Orienting Oneself with Fairy Stories Captiva B Chair: Jennifer Eastman Attebery Idaho State University Fairy-Tale Socialization and the Many Lands of Oz Jill Terry Rudy Brigham Young University From Android to Human – Examining Technology to Explore Identity and Humanity in The Lunar Chronicles Hannah Mummert University of Southern Mississippi The Gentry and The Little People: Resolving the Conflicting Legacy of Fairy Fiction Savannah Hughes University of Maine, Stonecoast 3 4. -

The Crowd Is Watching You

The crowd is watching you Interne Publieke social Medewerkers- communicatie media betrokkenheid COMMUNICATIE – ZIJN ER NOG GRENZEN? Merijn van den Berg 2010/2011 The crowd is watching you: Communicatie – zijn er nog grenzen? The crowd is watching you Communicatie – zijn er nog grenzen? Merijn van den Berg MSL Hogeschool Zeeland Opleiding Vestiging Amsterdam Bezoekadres Hoofdlocatie Communicatie Jan van Goyenkade 10 Edisonweg 4 2010/2011 1075 HP Amsterdam 4382 NW Vlissingen 00041143 T 020-3055900 T 0118-489000 twitter.com/merino1987 Vestiging Breda Afstudeerbegeleider Baronielaan 19 Katinka de Bakker linkedin.com/in/merino87 4818 PA Breda T 0118-489736 T 076-5242472 E [email protected] Begeleider www.hz.nl Bart van Wanrooij [email protected] T 06-14898389 E [email protected] www.msl.nl [email protected] 1 | P a g i n a The crowd is watching you: Communicatie – zijn er nog grenzen? Voorwoord Wie kan tegenwoordig alle online veranderingen nog bijhouden, de ontwikkelingen volgen elkaar zo snel op dat je altijd achter loopt. Dit is juist wat de online wereld zo interessant maakt voor mij. De constante beweging zorgt ervoor dat je nooit stil staat in je ontwikkeling, dagelijks is er wel iets nieuws te leren. Tijdens mijn vorige opleiding, IT Mediaproductie, ben ik mij pas echt gaan verdiepen in de wereld van social media. Internet werd met de dag interactiever en zeker als webdesigner moet je hierop inspelen. Eind 2005 maakte ik een Hyves profiel aan en sindsdien ben ik actief aan het netwerken geslagen. Twitter, Facebook, Linkedin, Myspace of zelfs het recent ontwikkelde Whoopaa, noem de sociale netwerksites maar op, je zal mij erop vinden. -

Handboek Starten Met Webcare

Starten met webcare handboek Aan de slag in 7 stappen Starten met webcare - Aan de slag in 7 stappen Jouw start voor effectieve webcare Je bent overtuigd van de kracht van webcare, maar hoe ga je ermee beginnen? Wat is er nodig om succesvol te worden? Wat zijn de eerste stappen om te starten met webcare en hoe zorg je dat je afdeling efficiënt gaat werken? In dit handboek delen we ons stappenplan waarmee jij concreet kan gaan starten met webcare. Daarnaast geven we je onze visie op webcare en vertellen we waarom webcare hét middel is waarmee je klanten extra service gaat bieden. Vervolgens kijken we naar de stappen die jij moet zetten om te beginnen met webcare. Door succesvolle verhalen van grote webcare organisaties als Ziggo, NS en Freo te combineren met onze eigen visie levert dit handboek je handvaten op. Zo kan jij vandaag nog aan de slag met webcare. In een notendop leert dit handboek je: • waarom webcare zorgt voor een glimlach bij de klant; • welke stappen jij concreet moet zetten om te starten met webcare; • een opzet van jouw webcareplan; • hoe je jouw toekomstige webcaresuccessen in kaart brengt. Team Coosto 2 Starten met webcare - Aan de slag in 7 stappen INHOUD 2 Jouw start voor effectieve webcare 4 Onze visie op webcare 7 Jouw stappenplan om te starten met webcare 12 Het leren kennen van je doelgroep met persona’s 15 Inspiratie van anderen 17 Het maken van een webcare plan 20 Breng het succes van jouw webcare afdeling in kaart 3 Onze visie op webcare Webcare wordt door organisaties op verschillende manieren ingezet afhankelijk van de doelstellingen. -

Textual Paralanguage and Its Implications for Marketing Communications†

Textual Paralanguage and Its Implications for Marketing Communications† Andrea Webb Luangratha University of Iowa Joann Peck University of Wisconsin–Madison Victor A. Barger University of Wisconsin–Whitewater a Andrea Webb Luangrath ([email protected]) is an Assistant Professor of Marketing at the University of Iowa, 21 E. Market St., Iowa City, IA 52242. Joann Peck ([email protected]) is an Associate Professor of Marketing at the University of Wisconsin– Madison, 975 University Ave., Madison, WI 53706. Victor A. Barger ([email protected]) is an Assistant Professor of Marketing at the University of Wisconsin–Whitewater, 800 W. Main St., Whitewater, WI 53190. The authors would like to thank the editor, associate editor, and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback, as well as Veronica Brozyna, Laura Schoenike, and Tessa Strack for their research assistance. † Forthcoming in the Journal of Consumer Psychology Abstract Both face-to-face communication and communication in online environments convey information beyond the actual verbal message. In a traditional face-to-face conversation, paralanguage, or the ancillary meaning- and emotion-laden aspects of speech that are not actual verbal prose, gives contextual information that allows interactors to more appropriately understand the message being conveyed. In this paper, we conceptualize textual paralanguage (TPL), which we define as written manifestations of nonverbal audible, tactile, and visual elements that supplement or replace written language and that can be expressed through words, symbols, images, punctuation, demarcations, or any combination of these elements. We develop a typology of textual paralanguage using data from Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. We present a conceptual framework of antecedents and consequences of brands’ use of textual paralanguage. -

Dark Places : Ecology, Place, and the Metaphysics of Horror Fiction

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 11 | 2015 Expressions of Environment in Euroamerican Culture / Antique Bodies in Nineteenth Century British Literature and Culture Dark Places : Ecology, Place, and the Metaphysics of Horror Fiction Brad Tabas Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/7012 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.7012 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Brad Tabas, “Dark Places : Ecology, Place, and the Metaphysics of Horror Fiction”, Miranda [Online], 11 | 2015, Online since 10 July 2015, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/7012 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.7012 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Dark Places : Ecology, Place, and the Metaphysics of Horror Fiction 1 Dark Places : Ecology, Place, and the Metaphysics of Horror Fiction Brad Tabas The world is increasingly unthinkable—a world of planetary disasters, emerging pandemics, tectonic shifts, strange weather, oil-drenched seascapes, and the furtive, always-looming threat of extinction. In spite of our daily concerns, wants, and desires, it is increasingly difficult to comprehend the world in which we live and of which we are a part. To confront this idea is to confront an absolute limit to our ability to adequately understand the world at all—an idea that has been a central motif of the horror genre for some time. (Thacker 1) 1 Horror fictions are very much about ambiance, place, surroundings and environment. While lesser examples of the genre use stock scenarios like haunted houses, misty graveyards, and god-forsaken rock outcroppings, most of the finest pieces of horror writing explore the expression of place in highly specific and deeply innovative ways. -

What Chatbot Developers Could Learn from Webcare Employees in Adopting a Conversational Human Voice

Pre-print of full paper presented at CONVERSATIONS 2019 - an international workshop on chatbot research, November19-20, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. The final authenticated version of the paper is available online at https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39540-7_4 Creating Humanlike Chatbots: What Chatbot Developers Could Learn From Webcare Employees In Adopting A Conversational Human Voice Christine Liebrecht1 and Charlotte van Hooijdonk2 1 Tilburg University, PO Box 90153, 5000 LE Tilburg, The Netherlands 2 VU Amsterdam, De Boelelaan 1105, 1081 HV, Amsterdam, The Netherlands [email protected] [email protected] Abstract. Currently, conversations with chatbots are perceived as unnatural and impersonal. One way to enhance the feeling of humanlike responses is by imple- menting an engaging communication style (i.e., Conversational Human Voice (CHV); Kelleher, 2009) which positively affects people’s perceptions of the or- ganization. This communication style contributes to the effectiveness of online communication between organizations and customers (i.e., webcare). This com- munication style is of high relevance to chatbot design and development. This project aimed to investigate how insights on the use of CHV in organizations’ messages and the perceptions of CHV can be implemented in customer service automation. A corpus study was conducted to investigate which linguistic ele- ments are used in organizations’ messages. Subsequently, an experiment was conducted to assess to what extent linguistic elements contribute to the perception of CHV. Based on these two studies, we investigated whether the amount of CHV can be identified automatically. These findings could be used to design human- like chatbots that use a natural and personal communication style like their hu- man conversation partner. -

Examining Consumers' Responses to Negative Electronic Word-Of-Mouth

Examining Consumers’ Responses to Negative Electronic Word-of-Mouth on Social Media: The Effect of Perceived Credibility on Brand Attitude and Purchase Intention XIE Minghua Student No. 15250962 Bachelor of social science (Honors) in Communication -- Public Relations and Advertising Major Abstract Consumers nowadays are increasingly engaging in electronic word-of-mouth communication to share their experience with brands or engage in the pre-purchase information search process. Such communication online shows a significant influence on consumers’ purchase decision making. As consumers tend to trust other consumers more than companies, eWOM is always considered to be more credible as compared to other paid media. Therefore, the perceived credibility of eWOM is always regarded as a key driver of the unignorable impact of eWOM. Moreover, negative word-of-mouth is found out to be more influential than the positive or neutral ones, as they are perceived to be more informative and diagnostic. Therefore, this research aimed at investigating the impact of perceived credibility of negative eWOM on observing consumers’ reactions, with regard to their post-message brand attitudes and purchase intentions. In addition, the researcher also paid attention to whether such impact would be affected by consumers’ prior brand attitudes and company’s eWOM intervening strategy (i.e., webcare). The results indicated that high perceived credibility of negative eWOM negatively affects consumers’ post-message brand attitudes and purchase intentions. And companies’