AN ABSTRACT of the THESIS of Holly Michelle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virtual Enrichment Ideas

CACFP At-Risk Afterschool Meals Enrichment Week 1 Date Activities ● National Geographic: Weird Nature Quiz. Go to the webpage and take the quiz to learn about weird things in nature. (science) https://kids.nationalgeographic.com/games/quizzes/quiz- whiz-weird-nature/ ● Check out art at one of the most famous museums in the world, the “MET” or Metropolitan Museum of Art. Go to the time machine webpage here: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/online-features/metkids/time-machine Click on “Africa,” then click “PUSH.” Click on the pieces of art one at a time and go through the experiences in the right column (like listen, watch, discover, etc.). (art, history) ● Learn how to make a time capsule! Go to the webpage. (various subjects) https://family.gonoodle.com/activities/how-to-make-a-time-capsule ● Inventions by Kids! Seed Launching Backpack. Go to the webpage and watch the video. (science, tech) https://thekidshouldseethis.com/post/seed-launching-backpack-a-3d-printed- pollinator-friendly-invention ● Bone Strength video from NFL. Go to the webpage to learn how to increase bone strength through nutrition and exercise! (science, phys ed) https://family.gonoodle.com/activities/bone- strength ● Watch live footage of African Animals. Go to the webpage and click on “African Wildlife.” Write a list of animals you see, or draw them. (science, social studies) https://explore.org/livecams ● Storyline Online- Oh the Places You’ll Go, read by Michelle Obama. Go to the webpage and read along or listen to the book. (language arts) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nVpHc8wsRKE ● Kennedy Center: World of Music. -

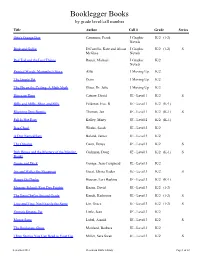

Booklegger Books by Grade Level/Call Number

Booklegger Books by grade level/call number Title Author Call # Grade Series Otto's Orange Day Cammuso, Frank J Graphic K/2 (1-2) Novels Bink and Gollie DiCamillo, Kate and Alison J Graphic K/2 (1-2) S McGhee Novels Red Ted and the Lost Things Rosen, Michael J Graphic K/2 Novels Painted Words: Marianthe's Story Aliki J Moving Up K/2 The Empty Pot Demi J Moving Up K/2 The Fly on the Ceiling: A Math Myth Glass, Dr. Julie J Moving Up K/2 Dinosaur Hunt Catrow, David JE - Level 1 K/2 S Billy and Milly, Short and Silly Feldman, Eve. B JE - Level 1 K/2 (K-1) Rhyming Dust Bunnie Thomas, Jan JE - Level 1 K/2 (K-1) S Fall Is Not Easy Kelley, Marty JE - Level 2 K/2 (K-1) Baa-Choo! Weeks, Sarah JE - Level 2 K/2 A Dog Named Sam Boland, Janice JE - Level 3 K/2 The Octopus Cazet, Denys JE - Level 3 K/2 S Dirk Bones and the Mystery of the Missing Cushman, Doug JE - Level 3 K/2 (K-1) S Books Goose and Duck George, Jean Craighead JE - Level 3 K/2 Iris and Walter the Sleepover Guest, Elissa Haden JE - Level 3 K/2 S Happy Go Ducky Houran, Lori Haskins JE - Level 3 K/2 (K-1) Monster School: First Day Frights Keane, David JE - Level 3 K/2 (1-2) The Best Chef in Second Grade Kenah, Katherine JE - Level 3 K/2 (1-2) S Ling and Ting: Not Exactly the Same Lin, Grace JE - Level 3 K/2 (1-2) S Emma's Strange Pet Little, Jean JE - Level 3 K/2 Mouse Soup Lobel, Arnold JE - Level 3 K/2 S The Bookstore Ghost Maitland, Barbara JE - Level 3 K/2 Three Stories You Can Read to Your Cat Miller, Sara Swan JE - Level 3 K/2 S September 2013 Pleasanton Public Library Page 1 of -

Final A1 8-806

www.tooeletranscript.com TUESDAY TOOELETRANSCRIPT Benson Grist Mill the perfect backdrop for beloved American musical. ULLETIN See B1 B August 8, 2006 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL. 113 NO. 21 50 cents Four child Aye! ‘Pirates’ film crew spied on Flats sex abuse by Jesse Fruhwirth STAFF WRITER There are no plans to change “Pirates of the cases hit Caribbean” to “Pirates of the West Desert.” Nonetheless, The Tooele local court Transcript- B u l l e t i n EDITOR’S NOTE: The contents of has con- this story may be offensive to some firmed that readers. J o h n n y by Jesse Fruhwirth Depp and STAFF WRITER the crew of Several unrelated but dreadful the block- charges of sex crimes against buster film children are making their way franchise photo/ Disney Enterprise Inc. through the court system in were at the Tooele. Second only to drug Bonneville Johhny Depp in “Dead’s Man Chest” charges, sex crimes against chil- Salt Flats dren account for a large share of Friday film- first-degree felonies on the court ing a scene for the upcoming calendar. third installment. The most recent charge filed Utah Gov. Jon Huntsman is against 21-year-old Tanisha had a secret lunch at the Salt Magness who faces a first-degree Flats Friday. He met with the felony charge of rape of a child. cast and crew of the next Magness made her initial appear- installment of “The Pirates of ance in court Monday, July 31. the Caribbean” series, which She was released on her own wrapped a one-day filming recognizance, but ordered to stay engagement near Wendover. -

Brown Bear Books Books Books Books

WINDMILL BOOKS WINDMILL BOOKS WINDMILL WINDMILL BROWN BEAR WINDMILL BROWN BEAR BOOKS BOOKS BOOKS BOOKS Ashley Brown Chairman [email protected] Ashley Brown Chairman [email protected] Anne O’Daly Children’s Publisher [email protected] 2018 BROWN Anne O’Daly Children’s Publisher [email protected] 2018 BROWN Lindsey Lowe Editorial Director [email protected] Lindsey Lowe Editorial Director [email protected] Audrey Curl Marketing and Rights [email protected] Audrey Curl Marketing and Rights [email protected] Unit 1/D Leroy House BEAR WINDMILL Unit 1/D Leroy House BEAR WINDMILL 436 Essex Road 436 Essex Road London N1 3PQ London N1 3PQ B B United Kingdom BEAR BOOKS ROWN BOOKS BOOKS United Kingdom BEAR BOOKS ROWN BOOKS BOOKS Tel: +44 (0)20 3176 8603 Tel: +44 (0)20 3176 8603 www.windmillbooks.co.uk www.windmillbooks.co.uk www.brownbearbooks.co.uk www.brownbearbooks.co.uk 2018 2018 WB_CAT18_COV_4.5_spine_final.indd 1 09/03/2018 18:17 WB_CAT18_COV_4.5_spine_final.indd 1 09/03/2018 18:17 CONTENTS Frontlist ..................................................................................................................... 2 UK Trade Titles ........................................................................................................ 20 Fast Track ................................................................................................................ 26 Facts at your Fingertips ........................................................................................ -

Wednesday, March 18, 2020 2:30 Pm

1 Wednesday, March 18, 2020 2:30 p.m. - 3:15 p.m. Pre-Opening Refreshment Ballroom Foyer ********** Wednesday, March 18, 2020 3:30 p.m. - 4:15 p.m. Opening Ceremony Ballroom Host: Jeri Zulli, Conference Director Welcome from the President: Dale Knickerbocker Guest of Honor Reading: Jeff VanderMeer Ballroom “DEAD ALIVE: Astronauts versus Hummingbirds versus Giant Marmots” Host: Benjamin J. Robertson University of Colorado, Boulder ********** Wednesday, March 18, 2020 4:30 p.m. - 6:00 p.m. 1. (GaH) Cosmic Horror, Existential Dread, and the Limits of Mortality Belle Isle Chair: Jude Wright Peru State College Dead Cthulhu Waits Dreaming of Corn in June: Intersections Between Folk Horror and Cosmic Horror Doug Ford State College of Florida The Immortal Existential Crisis Illuminates The Monstrous Human in Glen Duncan's The Last Werewolf Jordan Moran State College of Florida Hell . With a Beach: Christian Horror in Michael Bishop's "The Door Gunner" Joe Sanders Shadetree Scholar 2 2. (CYA/FTV) Superhero Surprise! Gender Constructions in Marvel, SpecFic, and DC Captiva A Chair: Emily Midkiff Northeastern State University "Every Woman Has a Crazy Side"? The Young Adult and Middle Grade Feminist Reclamation of Harley Quinn Anastasia Salter University of Central Florida An Elaborate Contraption: Pervasive Games as Mechanisms of Control in Ernest Cline's Ready Player One Jack Murray University of Central Florida 3. (FTFN/CYA) Orienting Oneself with Fairy Stories Captiva B Chair: Jennifer Eastman Attebery Idaho State University Fairy-Tale Socialization and the Many Lands of Oz Jill Terry Rudy Brigham Young University From Android to Human – Examining Technology to Explore Identity and Humanity in The Lunar Chronicles Hannah Mummert University of Southern Mississippi The Gentry and The Little People: Resolving the Conflicting Legacy of Fairy Fiction Savannah Hughes University of Maine, Stonecoast 3 4. -

Dark Places : Ecology, Place, and the Metaphysics of Horror Fiction

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 11 | 2015 Expressions of Environment in Euroamerican Culture / Antique Bodies in Nineteenth Century British Literature and Culture Dark Places : Ecology, Place, and the Metaphysics of Horror Fiction Brad Tabas Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/7012 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.7012 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Brad Tabas, “Dark Places : Ecology, Place, and the Metaphysics of Horror Fiction”, Miranda [Online], 11 | 2015, Online since 10 July 2015, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/7012 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.7012 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Dark Places : Ecology, Place, and the Metaphysics of Horror Fiction 1 Dark Places : Ecology, Place, and the Metaphysics of Horror Fiction Brad Tabas The world is increasingly unthinkable—a world of planetary disasters, emerging pandemics, tectonic shifts, strange weather, oil-drenched seascapes, and the furtive, always-looming threat of extinction. In spite of our daily concerns, wants, and desires, it is increasingly difficult to comprehend the world in which we live and of which we are a part. To confront this idea is to confront an absolute limit to our ability to adequately understand the world at all—an idea that has been a central motif of the horror genre for some time. (Thacker 1) 1 Horror fictions are very much about ambiance, place, surroundings and environment. While lesser examples of the genre use stock scenarios like haunted houses, misty graveyards, and god-forsaken rock outcroppings, most of the finest pieces of horror writing explore the expression of place in highly specific and deeply innovative ways. -

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin To cite this version: Denis-Constant Martin. Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa. African Minds, Somerset West, pp.472, 2013, 9781920489823. halshs-00875502 HAL Id: halshs-00875502 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00875502 Submitted on 25 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Sounding the Cape Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin AFRICAN MINDS Published by African Minds 4 Eccleston Place, Somerset West, 7130, South Africa [email protected] www.africanminds.co.za 2013 African Minds ISBN: 978-1-920489-82-3 The text publication is available as a PDF on www.africanminds.co.za and other websites under a Creative Commons licence that allows copying and distributing the publication, as long as it is attributed to African Minds and used for noncommercial, educational or public policy purposes. The illustrations are subject to copyright as indicated below. Photograph page iv © Denis-Constant -

Booklegger Books by Grade Level/Title

Booklegger Books by grade level/title Title Author Call # Grade Series Abiyoyo Seeger, Pete JPB K/2 S Agent A to Agent Z Rash, Andy JPB K/2 And the Dish Ran Away with the Spoon Stevens, Janet & JPB K/2 Susan Stevens Crummel Arnie the Doughnut Keller, Laurie JPB K/2 Art McDonnell, Patrick JPB K/2 Arte (Art in Spanish) McDonnell, Patrick Sp JPB K/2 Astronaut Handbook McCarthy, Meghan JPB K/2 Baa-Choo! Weeks, Sarah JE - Level 2 K/2 Babies in the Bayou Arnosky, Jim JPB K/2 The Baby BeeBee Bird Massie, Diane JPB K/2 Redfield Bad Kitty Bruel, Nick JPB K/2 S Baghead Krosoczka, Jarrett J. JPB K/2 Bark, George Feiffer, Jules JPB K/2 Baron Von Baddie and the Ice Ray Incident McClements, George JPB K/2 Bean Thirteen McElligott, Matthew JPB K/2 Bedhead Palatini, Margie JPB K/2 Beetle McGrady Eats Bugs! McDonald, Megan JPB K/2 Behind the Mask Choi, Yangsook JPB K/2 Belly Button Boy Maloney, Peter JPB K/2 Benny: An Adventure Story Graham, Bob JPB K/2 Bertie Was a Watchdog Walton, Rick JPB K/2 The Best Chef in Second Grade Kenah, Katherine JE - Level 3 K/2 (1-2) S Big Bug Surprise Gran, Julia JPB K/2 Billy and Milly, Short and Silly Feldman, Eve. B JE - Level 1 K/2 (K-1) September 2013 Pleasanton Public Library Page 1 of 42 Title Author Call # Grade Series Bink and Gollie DiCamillo, Kate and J Graphic K/2 (1-2) S Alison McGhee Novels Bob Pearson, Tracey JPB K/2 Campbell The Book of Beasts Nesbit, Edith JPB K/2 The Bookstore Ghost Maitland, Barbara JE - Level 3 K/2 Boxes for Katje Fleming, Candace JPB K/2 Bridget Fidget and the Most Perfect Pet Berger, Joe JPB K/2 (K-1) Bubba the Cowboy Prince Ketteman, Helen JPB K/2 Bubble Gum, Bubble Gum Wheeler, Lisa JPB K/2 Buffalo Music Fern, Tracey E. -

Wächter Der Wüste

Präsentiert WÄCHTER DER WÜSTE - AUCH KLEINE HELDEN KOMMEN GANZ GROSS RAUS Von den Produzenten von „Unsere Erde“ Ein Film von James Honeyborne Erzählt von Rufus Beck Kinostart: 20. November 2008 PRESSEHEFT PRESSEBETREUUNG filmpresse meuser in good company PR GmbH gisela meuser Ariane Kraus (Geschäftsführerin) niddastr. 64 h Deike Stagge 60329 frankfurt Rankestraße 3 10789 Berlin Tel.: 069 / 40 58 04 – 0 Tel: 030 / 880 91 – 550 Fax: 069 / 40 58 04 - 13 Fax: 030 / 880 91 - 703 [email protected] [email protected] Über unsere Homepage www.centralfilm.de haben Sie die Möglichkeit, sich für die Presse- Lounge zu akkreditieren. Dort stehen Ihnen alle Pressematerialien, Fotos und viele weitere Informationen als Download zur Verfügung. 2 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS STAB, TECHNISCHE DATEN KURZINHALT, PRESSENOTIZ PRODUKTIONSNOTIZEN ÜBER ERDMÄNNCHEN DIE BBC NATURAL HISTORY UNIT DER STAB REGISSEUR JAMES HONEYBORNE PRODUZENT JOE OPPENHEIMER PRODUZENT TREVOR INGMAN KAMERAMANN BARRIE BRITTON KAMERAMANN MARK PAYNE GILL CUTTER JUSTIN KRISH TONMEISTER CHRIS WATSON KOMPONISTIN SARAH CLASS ERZÄHLER RUFUS BECK 3 STAB Regie James Honeyborne Produzent Joe Oppenheimer Trevor Ingman Kamera Barrie Britton Mark Payne Gill Ton Chris Watson Schnitt Justin Krish Musik Sarah Class TECHNISCHE DATEN Länge 83 Minuten Bildformat Cinemascope Tonformat Dolby Digital 4 KURZINHALT WÄCHTER DER WÜSTE dokumentiert in atemberaubenden Bildern das aufregende Leben einer Erdmännchen-Familie in der Kalahari-Wüste. Der Film erzählt von der Geburt des kleinen Erdmännchens Kolo, seinem Aufwachsen und den täglichen Herausforderungen in der Wüste. Kolo macht seine ersten Schritte in eine Welt voller Abenteuer und tödlicher Gefahren und lernt vom großen Bruder die entscheidenden Lektionen zum Überleben. Denn um in der Kalahari groß zu werden, muss man wachsam sein, seine Feinde kennen und auch während der Dürre genügend Nahrung finden. -

Gothic Hybridities: Interdisciplinary, Multimodal and Transhistorical Approaches

The 14th International Gothic Association Conference Hosted by the Manchester Centre for Gothic Studies Manchester, July 31st-August 3rd, 2018 Gothic Hybridities: Interdisciplinary, Multimodal and Transhistorical Approaches Tuesday: July 31st: Registration (12 Noon - 5pm) – Business School Stalls, All Saints Campus, M15 6BH 4:00-5.45pm - *IGA Postgraduate Researchers Board Games Social*, Conference Suite, Manchester Met Students’ Union Building, 21 Higher Cambridge Street, M15 6AD - FREE, booking required1 7:00pm - Opening address by Professor Malcolm Press, Vice-Chancellor of Manchester Metropolitan University, followed by wine reception, Manchester Art Gallery, Mosley Street, M2 3JL. All week: Gothic Manchester Festival Exhibition, ‘A Motley Brew’, Sandbar, 120 Grosvenor Street, M1 7HL – FREE, no booking needed Wednesday: August 1st Registration desk hours: 8am-5pm Session 1: 09:00-10:30am Panel 1a (4.06b): Frankenstein's European Sources Chair: Dale Townshend 1. The Creative Grotesque: Dantesque Allusion in Frankenstein – Alison Milbank, Nottingham University 2. Mary Shelley's Quixotic Creatures: Cervantes and Frankenstein - Christopher Weimer, Oklahoma State University 3. Cobbling the 'German Gothic' into Frankenstein: Mary Shelley's Waking Nightmare and Fantasmagoriana - Maximiliaan van Woudenberg, Sheridan Institute of Technology Panel 1b (4.06a): Gothic Homes, Gothic Selves/Cells Chair: Ardel Haefele-Thomas 1. As Above, So Below: Attics and Basements as Gothic Sites in Stir of Echoes (1999) and The Skeleton Key (2005) - Laura Sedgwick, University of Stirling 2. ‘In These Rotting Walls’: Redefining the Gothic in Guillermo del Toro’s Crimson Peak - Shannon Payne, University of British Columbia, Canada 3. Punishment and Samuel R. Delany’s Gothic Utopias - Jason Haslam, Dalhousie University Panel 1c (4.05b): Contemporary Representations Chair: Jennifer Richards 1. -

Wild Cornwall 135 Spring 2018-FINAL.Indd

Wild CornwallISSUE 135 SPRING 2018 Boiling seas Fish in a frenzy A future for wildlife in Cornwall Our new CE looks ahead Wildlife Celebration FREE ENTRY to Caerhays gardens Clues in the grass Woven nests reveal Including pull-out a tiny rodent diary of events Contacts Kestavow Managers Conservation contacts General wildlife queries Other local wildlife groups Chief Executive Conservation Manager Wildlife Information Service and specialist group contacts Carolyn Cadman Tom Shelley ext 272 (01872) 273939 option 3 For grounded or injured bats in Head of Nature Reserves Marine Conservation Officer Investigation of dead specimens Cornwall - Sue & Chris Harlow Callum Deveney ext 232 Abby Crosby ext 230 (excluding badgers & marine (01872) 278695 mammals) Wildlife Veterinary Bat Conservation Trust Head of Conservation Marine Awareness Officer Investigation Centre Matt Slater ext 251 helpline 0345 130 0228 Cheryl Marriott ext 234 Vic Simpson (01872) 560623 Community Engagement Officer, Botanical Cornwall Group Head of Finance & Administration Reporting dead stranded marine Ian Bennallick Trevor Dee ext 267 Your Shore Beach Rangers Project Natalie Gibb animals & organisms [email protected] Head of Marketing & Fundraising natalie.gibb@ Marine Strandings Network Hotline 0345 2012626 Cornish Hedge Group Marie Preece ext 249 cornwallwildlifetrust.org.uk c/o HQ (01872) 273939 ext 407 Reporting live stranded marine Manager Cornwall Youth Engagement Officer, Cornwall Bird Watching & Environmental Consultants Your Shore Beach Ranger Project -

Australasian Nudibranch News

australasian nudibranchNEWS No.9 May 1999 Editors Notes Indications are readership is increasing. To understand how much I’m Chromodoris thompsoni asking readers to send me an email. Your participation, comments and feed- Rudman, 1983 back is appreciated. The information will assist in making decisions about dis- tribution and content. The “Nudibranch of the Month” featured on our website this month is Hexabranchus sanguineus. The whole nudibranch section will be updated by the end of the month. To assist anNEWS to provide up to date information would authors include me on their reprint mailing list or send details of the papers. Name Changes and Updates This column is to help keep up to date with mis-identifications or name changes. An updated (12th May 1999) errata for Neville Coleman’s 1989 Nudibranchs of the South Pacific is available upon request from the anNEWS editor. Hyselodoris nigrostriata (Eliot, 1904) is Hypselodoris zephyra Gosliner & © Wayne Ellis 1999 R. Johnson, 1999. Page 33C Nudibranchs of the South Pacific, Neville Coleman 1989 A small Australian chromodorid with Page 238C Nudibranchs and Sea Snails Indo Pacific Field Guide. an ovate body and a fairly broad mantle Helmut Debilius Edition’s One (1996) and Edition Two (1998). overlap. The mantle is pale pink with a blu- ish tinged background. Chromodoris loringi is Chromodoris thompsoni. The rhinophores are a translucent Page 34C Nudibranchs of the South Pacific. N. Coleman 1989. straw colour with cream dashes along the Page 32 Nudibranchs. Dr T.E. Thompson 1976 edges of the lamellae. The gills are coloured similiarly. In a recent paper in the Journal of Molluscan Studies, Valdes & Gosliner This species was described by Dr Bill have synonymised Miamira and Orodoris with Ceratosoma.