Low-Dose Naltrexone Therapy Improves Active Crohn's Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symptom Management in the Last Days of Life This Is About Managing Symptoms in the Last Days of Life Where the Dying Process Has Set In

Symptom management in the last days of life This is about managing symptoms in the last days of life where the dying process has set in. It assumes that the therapeutic aims are therefore: To allow the patient to die comfortably To support the family/carers and to start to prepare them for bereavement To discontinue any burdensome or irrelevant clinical procedures Key Prescribing Questions in the last days of life 1. Ahead of time Page a. Pre-emptive prescribing 1 b. Differences in specific circumstances 1 2. Once the oral route is lost a. What can be stopped? – managing co-morbidities at the end of life 2 (insulin; anti-epileptics; steroids; cardiac medicines) b. How to prescribe a syringe pump 3 i. Opioid conversion 4 ii. Combining drugs in a syringe – what can and can’t be mixed? 5 iii. Dosing other drugs 6 c. What can and can’t be given subcutaneously 7 3. Problems a. Uncontrolled symptoms (pain; restlessness; secretions; breathlessness; nausea; thirst) 8 b. Obtaining medicines out of hours 11 c. References and contact phone numbers 12 Pre-emptive prescribing The pre-emptive prescribing of p.r.n. medication for anticipated symptoms can avoid great distress. The cost is negligible and it saves time on the part of both families and out-of-hours health professionals. Typical maximum doses are described on page 22, but the doses needed by individuals vary widely: it is more important to assess the effectiveness of each p.r.n. before repeating or increasing doses – if a p.r.n. is ineffective, try a different approach or seek advice (see flow diagrams) A typical “pre-emptive p.r.n.” regimen for patients approaching the end of life might include: Morphine sulphate 2.5-5mg 1-4 hourly p.r.n. -

Topical Budesonide for Treating Giant Rectal Pseudopolyposis

ANTICANCER RESEARCH 25: 2961-2964 (2005) Topical Budesonide for Treating Giant Rectal Pseudopolyposis CHARALAMPOS PILICHOS1, ATHENA PREZA1, MARIA DEMONAKOU2, DIMITRIOS KAPATSORIS1 and CONSTANTINOS BOURAS1 1First Department of Internal Medicine and 2Department of Pathology, Sismanogleion Hospital, Athens, Greece Abstract. Pseudopolyps are a frequent finding in the course of Case Report inflammatory bowel disease. They are non-neoplastic lesions resulting from a regenerative and healing process that leaves A 45-year-old male patient was admitted to our service in July inflamed colonic mucosa in polypoid configuration. Data about 2002 for acute rectal bleeding. All laboratory tests were their management is lacking. "Giant" pseudopolyps can be normal, except an increase of aminotransferases level (>10 N) mistaken for adenocarcinomas and, as they rarely regress with and a serological profile consistent with acute hepatitis B or a medical management alone, a surgical resection is often required. flare of chronic hepatitis B (HbsAg +, HbsAb –, HbeAg –, A case of giant pseudopolyposis treated non-surgically, in a patient HbeAb +, HbcAb-IgM +). The patient underwent lower with concomitant ulcerative colitis and chronic hepatitis B, is gastro-intestinal endoscopy and multiple biopsies were taken reported, representing a co-morbidity complicating an eventual from a bulky rectal mass lesion (Figure 1). Histological study conservative treatment. The clinical implementation of topical revealed alterations compatible with inflammatory bowel budesonide was originally tested, resulting in clinical, endoscopic disease (IBD) with no dysplasia (Figure 2). Because of the and histological remission. Budesonide seems a promising therapy atypical macroscopic features and the high suspicion of rectal for IBD, particularly when a comorbidity with viral hepatitis exist. -

Practice Parameters for the Surgical Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis Howard Ross, M.D

PRACTICE PARAMETERS Practice Parameters for the Surgical Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis Howard Ross, M.D. • Scott R. Steele, M.D. • Mika Varma, M.D. • Sharon Dykes, M.D. Robert Cima, M.D. • W. Donald Buie, M.D. • Janice Rafferty, M.D. Prepared by the Standards Practice Task Force of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons he American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons the most common surgical indication for UC. Whether is dedicated to assuring high-quality patient care it is secondary to an inability to control symptoms, poor Tby advancing the science, prevention, and manage- quality of life, risks/side effects of chronic medical therapy ment of disorders and diseases of the colon, rectum, and (especially long-term corticosteroids), noncompliance, or anus. The Standards Committee is composed of Society growth failure, patients may opt for surgery in the elective members who are chosen because they have demonstrat- or semielective setting.3 Complete removal of all the poten- ed expertise in the specialty of colon and rectal surgery. tial disease-bearing tissue is theoretically curative in UC. This Committee was created to lead international efforts Operative options include an abdominal colectomy or total in defining quality care for conditions related to the co- proctocolectomy with either a permanent end ileostomy or lon, rectum, and anus. This is accompanied by develop- surgical construction of a “new” rectum through an IPAA ing Clinical Practice Guidelines based on the best available that restores GI continuity.4,5 All these procedures may evidence. These guidelines are inclusive, and not prescrip- be performed by using open or minimally invasive tech- tive. -

Future Directions for Intrathecal Pain Management 93

NEUROMODULATION: TECHNOLOGY AT THE NEURAL INTERFACE Volume 11 • Number 2 • 2008 http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/loi/ner ORIGINAL ARTICLE FBlackwell uturePublishing Inc Directions for Intrathecal Pain Management: A Review and Update From the Interdisciplinary Polyanalgesic Consensus Conference 2007 Timothy Deer, MD* • Elliot S. Krames, MD† • Samuel Hassenbusch, MD, PhD‡ • Allen Burton, MD§ • David Caraway, MD¶ • Stuart Dupen, MD** • James Eisenach, MD†† • Michael Erdek, MD‡‡ • Eric Grigsby, MD§§ • Phillip Kim, MD¶¶ • Robert Levy, MD, PhD*** • Gladstone McDowell, MD††† • Nagy Mekhail, MD‡‡‡ • Sunil Panchal, MD§§§ • Joshua Prager, MD¶¶¶ • Richard Rauck, MD**** • Michael Saulino, MD†††† •Todd Sitzman, MD‡‡‡‡ • Peter Staats, MD§§§§ • Michael Stanton-Hicks, MD¶¶¶¶ • Lisa Stearns, MD***** • K. Dean Willis, MD††††† • William Witt, MD‡‡‡‡‡ • Kenneth Follett, MD, PhD§§§§§ • Mark Huntoon, MD¶¶¶¶¶ • Leong Liem, MD****** • James Rathmell, MD†††††† • Mark Wallace, MD‡‡‡‡‡‡ • Eric Buchser, MD§§§§§§ • Michael Cousins, MD¶¶¶¶¶¶ • Ann Ver Donck, MD******* *Charleston, WV; †San Francisco, CA; ‡Houston, TX; §Houston, TX; ¶Huntington, WV; **Bellevue, WA; ††Winston Salem, NC; ‡‡Baltimore, MD; §§Napa, CA; ¶¶Wilmington, DE; ***Chicago, IL; †††Columbus, OH; ‡‡‡Cleveland, OH; §§§Tampa, FL; ¶¶¶Los Angeles, CA; ****Winston Salem, NC; ††††Elkings Park, PA; ‡‡‡‡Hattiesburg, MS; §§§§Colts Neck, NJ; ¶¶¶¶Cleveland, OH; *****Scottsdale, AZ; †††††Huntsville, AL; ‡‡‡‡‡Lexington, KY; §§§§§Iowa City, IA; ¶¶¶¶¶Rochester, NY; ******Nieuwegein, The Netherlands; ††††††Boston, MA; ‡‡‡‡‡‡La Jolla, CA; §§§§§§Switzerland; ¶¶¶¶¶¶Australia; and *******Brugge, Belgium ABSTRACT Background. Expert panels of physicians and nonphysicians, all expert in intrathecal (IT) therapies, convened in the years 2000 and 2003 to make recommendations for the rational use of IT analgesics, based on the preclinical and clinical literature known up to those times, presentations of the expert panels, discussions on current practice and standards, and the result of surveys of physicians using IT agents. -

Hyoscine Butylbromide, Levomepromazine, Metoclopramide, Midazolam, Ondansetron

TRUST WIDE/DIVISIONAL DOCUMENT Delete as appropriate Policy/Standard Operating Procedure/ Clinical Guideline Policy and Procedure for the T34 Ambulatory Syringe Pump DOCUMENT TITLE: in adults (Palliative Care) DOCUMENT ELHT/CP22 Version 5.3 NUMBER: DOCUMENT REPLACES Which ELHT/CP22 Version 5.2 Version LEAD EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR DGM AUTHOR(S): Note Syringe pump policy task and finish group chaired by should not include Palliative Medicine Consultant names TARGET AUDIENCE: Medical and Nursing Staff 1 To provide a clear governance framework to ensure a safe and consistent approach to the use of the T34 Ambulatory Syringe Pump DOCUMENT 2 To provide details of how to set up and administer PURPOSE: medication by a T34 Ambulatory Syringe Pump 3 To provide easily accessible information about the common medicines used in a Syringe Pump Clinical Practice Summary. Guidance on consensus approaches To be read in to managing palliative care symptoms. Lancashire and South conjunction with Cumbria consensus guidance – August 2017 (identify which internal C064 V5 Medicines Management Policy documents) IC24 V4 Aseptic non touch technique (ANTT) policy East Lancashire Hospital NHS Trust – Policies & Procedures, Protocols, Guidelines ELHT/CP22 v5.2 May 2020 Page 1 of 77 Nursing and Midwifery Council - Standards for Medicines Management 2015 Dickman et al (2016) The Syringe Driver, 4th edition, Oxford Press T. Mitten, (2000) Subcutaneous drug infusions, a review of problems and solutions. International Journal of Palliative Nursing Vol 7, No 2. Twycross et al (2017) 6th Edition Palliative Care SUPPORTING Formulary and Palliative Care Formulary online, REFERENCES accessed June 2018 Twycross R., Wilcock A., (2001) Symptom Management in Advanced Cancer 3rd edition Radcliffe medical press Oxon. -

Approach to the Poisoned Patient

PED-1407 Chocolate to Crystal Methamphetamine to the Cinnamon Challenge - Emergency Approach to the Intoxicated Child BLS 08 / ALS 75 / 1.5 CEU Target Audience: All Pediatric and adolescent ingestions are common reasons for 911 dispatches and emergency department visits. With greater availability of medications and drugs, healthcare professionals need to stay sharp on current trends in medical toxicology. This lecture examines mind altering substances, initial prehospital approach to toxicology and stabilization for transport, poison control center resources, and ultimate emergency department and intensive care management. Pediatric Toxicology Dr. James Burhop Pediatric Emergency Medicine Children’s Hospital of the Kings Daughters Objectives • Epidemiology • History of Poisoning • Review initial assessment of the child with a possible ingestion • General management principles for toxic exposures • Case Based (12 common pediatric cases) • Emerging drugs of abuse • Cathinones, Synthetics, Salvia, Maxy/MCAT, 25I, Kratom Epidemiology • 55 Poison Centers serving 295 million people • 2.3 million exposures in 2011 – 39% are children younger than 3 years – 52% in children younger than 6 years • 1-800-222-1222 2011 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers Toxic Exposure Surveillance System Introduction • 95% decline in the number of pediatric poisoning deaths since 1960 – child resistant packaging – heightened parental awareness – more sophisticated interventions – poison control centers Epidemiology • Unintentional (1-2 -

Sandostatin® Injection

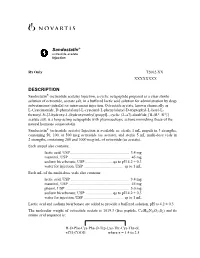

Sandostatin® octreotide acetate Injection Rx Only T2002-XX XXXXXXXX DESCRIPTION Sandostatin® (octreotide acetate) Injection, a cyclic octapeptide prepared as a clear sterile solution of octreotide, acetate salt, in a buffered lactic acid solution for administration by deep subcutaneous (intrafat) or intravenous injection. Octreotide acetate, known chemically as L-Cysteinamide, D-phenylalanyl-L-cysteinyl-L-phenylalanyl-D-tryptophyl-L-lysyl-L- threonyl-N-[2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)propyl]-, cyclic (2→7)-disulfide; [R-(R*, R*)] acetate salt, is a long-acting octapeptide with pharmacologic actions mimicking those of the natural hormone somatostatin. Sandostatin® (octreotide acetate) Injection is available as: sterile 1 mL ampuls in 3 strengths, containing 50, 100, or 500 mcg octreotide (as acetate), and sterile 5 mL multi-dose vials in 2 strengths, containing 200 and 1000 mcg/mL of octreotide (as acetate). Each ampul also contains: lactic acid, USP............................................................ 3.4 mg mannitol, USP .............................................................. 45 mg sodium bicarbonate, USP.............................qs to pH 4.2 ± 0.3 water for injection, USP ........................................ qs to 1 mL Each mL of the multi-dose vials also contains: lactic acid, USP ........................................................... 3.4 mg mannitol, USP .............................................................. 45 mg phenol, USP ................................................................ 5.0 mg sodium -

Acute Poisoning: Understanding 90% of Cases in a Nutshell S L Greene, P I Dargan, a L Jones

204 REVIEW Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.2004.027813 on 5 April 2005. Downloaded from Acute poisoning: understanding 90% of cases in a nutshell S L Greene, P I Dargan, A L Jones ............................................................................................................................... Postgrad Med J 2005;81:204–216. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.024794 The acutely poisoned patient remains a common problem Paracetamol remains the most common drug taken in overdose in the UK (50% of intentional facing doctors working in acute medicine in the United self poisoning presentations).19 Non-steroidal Kingdom and worldwide. This review examines the initial anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), benzodiaze- management of the acutely poisoned patient. Aspects of pines/zopiclone, aspirin, compound analgesics, drugs of misuse including opioids, tricyclic general management are reviewed including immediate antidepressants (TCAs), and selective serotonin interventions, investigations, gastrointestinal reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) comprise most of the decontamination techniques, use of antidotes, methods to remaining 50% (box 1). Reductions in the price of drugs of misuse have led to increased cocaine, increase poison elimination, and psychological MDMA (ecstasy), and c-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) assessment. More common and serious poisonings caused toxicity related ED attendances.10 Clinicians by paracetamol, salicylates, opioids, tricyclic should also be aware that severe toxicity can result from exposure to non-licensed pharmaco- -

8-GI Drugs Final

Gastrointestinal Drugs Subcommittee: Prozialeck, Walter (Chair) [email protected] Escher, Emanuel [email protected] Garrison, James C. [email protected] Henry, Matthew, [email protected] Weber, Donna R [email protected] Recommended Curriculum Equivalent: 1.5 h Acid Reducers and Drugs for the Treatment of Peptic Ulcer Disease Proton pump inhibitors First generation Second generation OMEPRAZOLE ESOMEPRAZOLE LANSOPRAZOLE PANTOPRAZOLE RABEPRAZOLE Learning Objectives Physiology and pathophysiology Describe the synthesis and mechanism of H+ secretion by the parietal cells Mechanism of action Describe the mechanism of action of proton pump inhibitors and why they are selective for the parietal cell proton pump. Actions on organ systems Describe the pharmacological effects of the drugs on gastric function. Are there effects on other organ systems? Pharmacokinetics Describe the pharmacokinetics of proton pump inhibitors? Are there significant differences among the different drugs in this class? Adverse effects, drug interactions and contraindications Describe the principal adverse effects of proton pump inhibitors. Describe the clinically important drug interactions of proton pump inhibitors. Describe the principal contraindications of proton pump inhibitors. Therapeutic uses Describe the current therapeutic uses of proton pump inhibitors. 1 Clinical Pharmacology Omeprazole is perceived to be the most potent of this drug class in inhibiting CYP2C19 activity and is proposed to have potential drug interactions with other drugs metabolized by this P450 isoform. Concern has been raised about potential inhibition of clopidogrel activation in patients taking both drugs concurrently. Current consensus is that in such patients clopidogrel with pantoprazole may be a safer choice to reduce the probability of a drug interaction involving CYP2C19. -

Question of the Day Archives: Monday, December 5, 2016 Question: Calcium Oxalate Is a Widespread Toxin Found in Many Species of Plants

Question Of the Day Archives: Monday, December 5, 2016 Question: Calcium oxalate is a widespread toxin found in many species of plants. What is the needle shaped crystal containing calcium oxalate called and what is the compilation of these structures known as? Answer: The needle shaped plant-based crystals containing calcium oxalate are known as raphides. A compilation of raphides forms the structure known as an idioblast. (Lim CS et al. Atlas of select poisonous plants and mushrooms. 2016 Disease-a-Month 62(3):37-66) Friday, December 2, 2016 Question: Which oral chelating agent has been reported to cause transient increases in plasma ALT activity in some patients as well as rare instances of mucocutaneous skin reactions? Answer: Orally administered dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) has been reported to cause transient increases in ALT activity as well as rare instances of mucocutaneous skin reactions. (Bradberry S et al. Use of oral dimercaptosuccinic acid (succimer) in adult patients with inorganic lead poisoning. 2009 Q J Med 102:721-732) Thursday, December 1, 2016 Question: What is Clioquinol and why was it withdrawn from the market during the 1970s? Answer: According to the cited reference, “Between the 1950s and 1970s Clioquinol was used to treat and prevent intestinal parasitic disease [intestinal amebiasis].” “In the early 1970s Clioquinol was withdrawn from the market as an oral agent due to an association with sub-acute myelo-optic neuropathy (SMON) in Japanese patients. SMON is a syndrome that involves sensory and motor disturbances in the lower limbs as well as visual changes that are due to symmetrical demyelination of the lateral and posterior funiculi of the spinal cord, optic nerve, and peripheral nerves. -

Malta Medicines List April 08

Defined Daily Doses Pharmacological Dispensing Active Ingredients Trade Name Dosage strength Dosage form ATC Code Comments (WHO) Classification Class Glucobay 50 50mg Alpha Glucosidase Inhibitor - Blood Acarbose Tablet 300mg A10BF01 PoM Glucose Lowering Glucobay 100 100mg Medicine Rantudil® Forte 60mg Capsule hard Anti-inflammatory and Acemetacine 0.12g anti rheumatic, non M01AB11 PoM steroidal Rantudil® Retard 90mg Slow release capsule Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitor - Acetazolamide Diamox 250mg Tablet 750mg S01EC01 PoM Antiglaucoma Preparation Parasympatho- Powder and solvent for solution for mimetic - Acetylcholine Chloride Miovisin® 10mg/ml Refer to PIL S01EB09 PoM eye irrigation Antiglaucoma Preparation Acetylcysteine 200mg/ml Concentrate for solution for Acetylcysteine 200mg/ml Refer to PIL Antidote PoM Injection injection V03AB23 Zovirax™ Suspension 200mg/5ml Oral suspension Aciclovir Medovir 200 200mg Tablet Virucid 200 Zovirax® 200mg Dispersible film-coated tablets 4g Antiviral J05AB01 PoM Zovirax® 800mg Aciclovir Medovir 800 800mg Tablet Aciclovir Virucid 800 Virucid 400 400mg Tablet Aciclovir Merck 250mg Powder for solution for inj Immunovir® Zovirax® Cream PoM PoM Numark Cold Sore Cream 5% w/w (5g/100g)Cream Refer to PIL Antiviral D06BB03 Vitasorb Cold Sore OTC Cream Medovir PoM Neotigason® 10mg Acitretin Capsule 35mg Retinoid - Antipsoriatic D05BB02 PoM Neotigason® 25mg Acrivastine Benadryl® Allergy Relief 8mg Capsule 24mg Antihistamine R06AX18 OTC Carbomix 81.3%w/w Granules for oral suspension Antidiarrhoeal and Activated Charcoal -

DBL™ Octreotide Solution for Injection Contains 0.05 Mg, 0.1 Mg Or 0.5 Mg of Octreotide As Octreotide Acetate

NEW ZEALAND DATA SHEET 1. PRODUCT NAME DBL™ Octreotide 0.05 mg/mL, 0.1 mg/mL and 0.5 mg/mL solution for injection 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each 1 mL vial of DBL™ Octreotide solution for injection contains 0.05 mg, 0.1 mg or 0.5 mg of octreotide as octreotide acetate. Excipients with known effect DBL™ Octreotide solution for injection contains less than 1 mmol (23 mg) sodium per dose; i.e. essentially ‘sodium-free’. For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM DBL™ Octreotide is a clear colourless solution for injection. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications For symptomatic control and reduction of growth hormone (GH) and IGF-1 plasma levels in patients with acromegaly who are inadequately controlled by surgery or radiotherapy. Octreotide treatment is also indicated for acromegalic patients unfit or unwilling to undergo surgery, or in the interim period until radiotherapy becomes fully effective. For the relief of symptoms associated with functional gastro-entero-pancreatic (GEP) endocrine tumours: Carcinoid tumours with features of the carcinoid syndrome Vasoactive intestinal peptide secreting tumours (VIPomas) Glucagonomas Gastrinomas/Zollinger-Ellis syndrome, usually in conjunction with proton pump inhibitors, or H2-antagonist therapy Insulinomas, for pre-operative control of hypoglycaemia and for maintenance therapy GRFomas. Octreotide is not an antitumour therapy and is not curative in these patients. For prevention of complications following pancreatic surgery. Version pfdoctri11020 Supersedes: pfdoctri10719 Page 1 of 16 Emergency management to stop bleeding and to protect from re-bleeding owing to gastro- oesophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis.