Justification and Emancipation: the Critical Theory of Rainer Forst. Edited by Amy Allen and Eduardo Mendieta. University Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Justification of Basic Rights: a Discourse-Theoretical Approach1 Rainer Forst

The Justification of Basic Rights: A Discourse-Theoretical Approach1 Rainer Forst 1. Justifying Basic Rights Very few people doubt that it is a fundamental demand of justice that members of legal- political normative orders ought to have legal rights that define their basic standing as subjects of such an order.2 But when it comes to the concrete understanding of such rights, debates abound. What is the nature of these rights – are they an expression of the sovereign will of individuals, or are they based on important human interests? How should these rights be justified – do they have a particular moral ground, and if so, only one or many? In what follows, I suggest a discourse theory of basic legal rights that answers such questions in a way that I argue is superior to rival approaches, such as a will-based or an interest-based theory of rights. The main argument runs as follows.3 Basic rights are reciprocally and generally valid – i.e. mutually justifiable – claims4 on others (agents or institutions) that they should do or refrain from doing certain things determined by the content of these rights. We call these rights basic or fundamental because they define the status of persons as full members of a normative order in such a way that they provide 1 Many thanks for helpful critical remarks to the editors of this journal, Lisette ten Haaf, Elaine Mak and Bertjan Wolthuis and to my critics at the occasion of the VWR conference in June 2016 to whom I will have the pleasure to reply: Laura Valentini, Marcus Düwell, Glen Newey and Stefan Rummens. -

Noumenal Power

Normative Orders Working Paper 02/2013 Noumenal Power Prof. Dr. Rainer Forst Cluster of Excellence The Formation of Normative Orders www.normativeorders.net Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main Grüneburgweg 1, Fach EXC 6, 60629 Frankfurt am Main [email protected] © 2013 by the author(s) 1 Noumenal Power by Rainer Forst 1. In political or social philosophy, we speak about power all the time. Yet the meaning of this important concept is rarely made explicit, especially in the context of normative discussions.1 But as with many other concepts, once one considers it more closely, fundamental problems arise, such as whether a power relation is necessarily a relation of subordination and domination. In the following, I suggest a novel understanding of what power is and what it means to exercise it. The title “noumenal power” might suggest that I am going to speak about a certain form of power in the world of ideas or of thought, and that this will be far removed from the reality of power as a social or institutional phenomenon. In Joseph Nye’s words, one might assume that I have only the “soft power” of persuasion in mind and not the “hard power” of coercion.2 Real and hard power, a “realist” might say, is about the empirical world, it is made of material stuff, like political positions, monetary means or, ultimately, military instruments of force. 1 There are of course exceptions, such as Philip Pettit’s work – see his recent book On the People’s Terms, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012 – as well as Ian Shapiro’s work, in particular Democratic Justice, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999, and The Real World of Democratic Theory, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011. -

Two Pictures of Justice." Justice, Democracy and the Right to Justification: Rainer Forst in Dialogue

Forst, Rainer. "Two Pictures of Justice." Justice, Democracy and the Right to Justification: Rainer Forst in Dialogue. Ed. Rainer Forst. : Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 3–26. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472544735.ch-001>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 16:30 UTC. Copyright © Rainer Forst and contributors, 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 1 Two Pictures of Justice Rainer Forst Professor of Political Theory and Philosophy Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany 1. At various times, human beings have made depictions of justice. She appears as the goddess Diké or Justitia, sometimes with, sometimes without a blindfold, though invariably with the sword and symbols of even-handedness and non-partisanship; one need only think, for example, of Lorenzetti’s ‘Allegory of Good Government’ in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena. Mostly she is depicted as beautiful and sublime, yet at other times also as hard and cruel, as in Klimt’s famous paintings for Vienna University (which were destroyed during the war). Studying such representations is a fascinating enterprise.1 However, the understanding of ‘picture’ which informs my remarks is a different, linguistic, one. In his Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein writes: ‘A picture held us captive. And we could not get outside it, for it lay in our language and language seemed to repeat it to us inexorably.’2 A picture of this kind shapes our language in a particular way, brings together the various usages of a word and thus constitutes its ‘grammar’. -

Reflexive Toleration – a Critical Inquiry Into Rainer Forst’S Theory of Toleration

Uppsala University Faculty of Theology Studies in Systematic Theology, Ethics, and Philosophy of Religion E 30 ECTS-credits Ethics of Religion Spring semester 2017 Master’s Thesis Author: Martin Langby Supervisor: Professor Elena Namli Reflexive Toleration – A Critical Inquiry into Rainer Forst’s Theory of Toleration Abstract This master’s thesis provides a critical inquiry into Rainer Forst’s theory of toleration, including a descriptive section and a normative critical stance of said theory. Being placed in the tradition of critical theory, also applied as the theoretical framework, and using a hermeneutics methodology when approaching the material, the aim is to provide a close reading of Forst’s texts. The research question of the thesis is What are the possibilities and limits of Forst’s theory of toleration when applied to a democratic political community? The descriptive section of Forst's theory of toleration includes sections comprising of what constitutes the domain of toleration, the components and foundation of toleration, and toleration in relation to virtue and politics. In essence, Forst proposes a principle of justification as the foundation of toleration, mainly derived from his political theory of justification, practiced in a reciprocal and universal manner of the participants in a system combined with a reflexive component. The critique includes components of toleration in relation to the need of tradition, ambivalence in relation to the claims of the intolerants, and how spontaneity is needed in contrast to the mechanistic view mainly proposed by Forst. Other sections of the critique include the relation of toleration and whom can participate in the domain of it, inter- and intra-group deviances regarding power and perspective, but also a discussion of toleration and religious minorities – mainly focused on bodily integrity. -

Toleration in Conflict: Past and Present Rainer Forst Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88577-5 - Toleration in Conflict: Past and Present Rainer Forst Frontmatter More information Toleration in Conflict Past and Present The concept of toleration plays a central role in pluralistic societies. It designates a stance which permits conflicts over beliefs and practices to persist while at the same time defusing them, because it is based on reasons for coexistence in conflict – that is, in continuing dissension. A critical examination of the concept makes clear, however, that its content and evaluation are profoundly contested matters and thus that the concept itself stands in conflict. For some, toleration was and is an expression of mutual respect in spite of far-reaching differences, but for others, it is a condescending, potentially repressive attitude and practice. Rainer Forst analyses these conflicts by reconstructing the philosophical and political discourse of toleration since antiquity. He demonstrates the diversity of the justifications and practices of toleration from the Stoics and early Christians to the present day and develops a systematic theory which he tests in discussions of contemporary conflicts over toleration. Rainer Forst is Professor of Political Theory and Philosophy at the Goethe University in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. In addition, he is Co-Director of the interdisciplinary Research Cluster ‘Formation of Normative Orders’ at the Goethe University. His books include Contexts of Justice, The Right to Justification and Justification and Critique. In 2012, he received the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize, the highest honour awarded to German researchers. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88577-5 - Toleration in Conflict: Past and Present Rainer Forst Frontmatter More information ideas in context Edited by David Armitage, Jennifer Pitts, Quentin Skinner and James Tully The books in this series will discuss the emergence of intellectual traditions and of related new disciplines. -

Jeffrey Flynn August 2013

JEFFREY FLYNN AUGUST 2013 DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY [email protected] FORDHAM UNIVERSITY, LINCOLN CENTER CAMPUS OFFICE: 212-636-7928 NEW YORK, NY 10023 ACADEMIC POSITIONS 2013 - Associate Professor Fordham University 2007 - 2013 Assistant Professor Fordham University 2006 - 2007 Assistant Professor Middlebury College 2005 - 2006 Instructor Middlebury College 2004 - 2005 Visiting Instructor Middlebury College EDUCATION Northwestern University Ph.D., Philosophy 2006 Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt DAAD Fellowship 2002-2003 Syracuse University Graduate Program in Philosophy 1997-1998 University of Notre Dame B.A., Philosophy & Anthropology 1995 AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION Critical Social Theory (esp. Habermas) Social and Political Philosophy Human Rights and Humanitarianism FELLOWSHIPS Member, Institute for Advanced Study, School of Social Science, Princeton, NJ, 2013-14. Mellon Sawyer Seminar Faculty Fellow, “Democratic Citizenship and the Recognition of Cultural Differences,” CUNY Graduate Center Seminar, 2012-13. NEH Summer Institute, “Human Rights in Conflict: Interdisciplinary Perspectives,” CUNY Graduate Center, June 24-July 28, 2006. DAAD Fellow, German Academic Exchange Service, 2002-2003. PUBLICATIONS Reframing the Intercultural Dialogue on Human Rights: A Philosophical Approach (Routledge, forthcoming). “System and Lifeworld in Habermas’s Theory of Democracy,” Philosophy & Social Criticism (forthcoming). “Truth, Objectivity, and Experience after the Pragmatic Turn: Bernstein on Habermas’s ‘Kantian Pragmatism,’” in Richard J Bernstein and the Pragmatist Turn in Contemporary Philosophy, Judith M. Green, ed. (Palgrave Macmillan, forthcoming). “Human Rights in History and Contemporary Practice: Source Materials for Philosophy,” in Philosophical Dimensions of Human Rights, Claudio Corradetti, ed. (Springer, 2012). Jeffrey Flynn – Curriculum Vitae, p. 2 “Two Models of Human Rights: Extending the Rawls-Habermas Debate,” in Habermas and Rawls: Disputing the Political, Gordon Finlayson and Fabian Freyenhagen, eds. -

Political Legitimacy and Democracy in Transnational Perspective

Political Legitimacy and Democracy in Transnational Perspective Rainer Forst and Rainer Schmalz-Bruns (eds) ARENA Report No 2/11 RECON Report No 13 Political Legitimacy and Democracy in Transnational Perspective Rainer Forst and Rainer Schmalz-Bruns (eds) Copyright ARENA and authors ISBN (print) 978-82-93137-30-6 ISBN (online) 978-82-93137-80-1 ARENA Report Series (print) | ISSN 0807-3139 ARENA Report Series (online) | ISSN 1504-8152 RECON Report Series (print) | ISSN 1504-7253 RECON Report Series (online) | ISSN 1504-7261 Printed at ARENA Centre for European Studies University of Oslo P.O. Box 1143, Blindern N-0318 Oslo, Norway Tel: + 47 22 85 87 00 Fax: + 47 22 85 87 10 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.arena.uio.no http://www.reconproject.eu Oslo, March 2011 Cover picture: ‘Untitled… Homage to Mark Rothko’ by Mike Lusk. © Mike Lusk 2007 Preface Reconstituting Democracy in Europe (RECON) is an Integrated Project supported by the European Commission’s Sixth Framework Programme for Research, Priority 7 ‘Citizens and Governance in a Knowledge-based Society’. The five-year project has 21 partners in 13 European countries and New Zealand, and is coordinated by ARENA – Centre for European Studies at the University of Oslo. RECON takes heed of the challenges to democracy in Europe. It seeks to clarify whether democracy is possible under conditions of pluralism, diversity and complex multilevel governance. See more on the project at www.reconproject.eu. The present report is part of RECON’s work package 1 ‘Theoretical Framework’, which seeks to develop an overarching theoretical approach to the study of European democracy. -

Politikon: IAPSS Political Science Journal Vol. 25

Politikon: IAPSS Political Science Journal Vol. 25 1 Politikon: IAPSS Political Science Journal Vol. 25 Volume 25: December 2014 Special Conference Volume of IAPSS Autumn Convention 2014, Nijmegen, The Netherlands Editor-in-Chief Vit Simral (Czech Republic) Editorial Board Caitlin Bagby (USA) Péter Király (Hungary) Caroline Ronsin (France) Eltion Meka (USA) Laurens Visser (Australia) 2 Politikon: IAPSS Political Science Journal Vol. 25 Table of Contents Editorial Note 4 Rights from the Other Side of the Line: Postcolonial perspectives on human rights Owen Brown 5 Perspectives for a Social Integration of Human rights in the Muslim world Efrem Garlando 27 Human Rights Relations between Europe and Russia A genealogy of diverging concepts Amelie Harbisch 37 Country Specifics of a Universal Right? Freedom of political speech in the Slovak Republic Max Steuer 56 “Positionality” and “Performativity”: Feminist theory and gender studies’ contributions to the construction of the concept of media literacy Raquel Tebaldi 80 Political Cartoon in Ecuador: Exploring a chilling-effect after the sanction against ‘Bonil’ and El Universo David Vásquez Léon 95 Theories of Universal Human Rights and the Individual’s Perspective Linda Walter 120 Call for Papers for Politikon 142 3 Politikon: IAPSS Political Science Journal Vol. 25 Editorial Note Dear Reader, You have before you a special Politikon volume comprised of works presented at the Autumn Convention of the International Association of Political Science Students in Nijmegen, The Netherlands, in October 2014. We selected in total seven original papers that show the wide variety of topics presented at the Convention: from post-colonial perspectives on human rights, through freedom of speech issues in Slovakia, feminist theory’s contribution to the construction of the concept of media literacy, to political cartoons in Ecuador. -

55Th Frank Fraser Potter Memorial Lecture in Philosophy - Amy Allen

55th Frank Fraser Potter Memorial Lecture in Philosophy - Amy Allen MATT STICHTER: Good evening, everyone. My name is Matt Stichter. I'm a Professor of Philisophy in the School of Politics, Philosophy, and Public Affairs here at WSU. My colleagues and I would like to welcome you all to the 55th Memorial Lecture celebrating the Potters and their legacy. For those of you who it's the first time here, this annual Memorial Lecture series serves to commemorate the accomplishments of Professor Frank Potter, and his wife Irene, and what they gave to WSU and the community. Frank Potter was actually the first philosopher here at WSU, and was instrumental in starting the Philosophy Department here. In addition, he and his wife Irene regularly hosted students at their home over on B Street for intellectual discussions, for music. They'd play chess. Apparently they'd also get very well-fed. And this intellectual stimulation and generosity on behalf of the Potters really made a deep impact on their students. Furthermore, another accomplishment of the Potters can be seen in the mentoring that Frank Potter did with his students, because he mentored 10 Rhodes scholars over the course of here at WSU. And this Potter lecture series was actually started and funded by one of their students, Mildred Bissinger. And over the years, people who knew the Potters or know about their legacy have generously donated to help keeping this going now in its 55th year. And overall, I think this program helped serve some of the university's grand initiatives challenges with respect to social political issues, creating a more equitable and just society. -

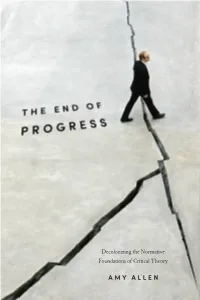

Decolonizing the Normative Foundations of Critical Theory

Decolonizing the Normative Foundations of Critical Theory AMY ALLEN THE END OF PROGRESS new directions in critical theory New Directions in Critical Theory amy allen, general editor New Directions in Critical Theory presents outstanding classic and contem- porary texts in the tradition of critical social theory, broadly construed. The series aims to renew and advance the program of critical social theory, with a particular focus on theorizing contemporary struggles around gender, race, sexuality, class, and globalization and their complex interconnections. Narrating Evil: A Postmetaphysical Theory of Reflective Judgment, María Pía Lara The Politics of Our Selves: Power, Autonomy, and Gender in Contemporary Critical Theory, Amy Allen Democracy and the Political Unconscious, Noëlle McAfee The Force of the Example: Explorations in the Paradigm of Judgment, Alessandro Ferrara Horrorism: Naming Contemporary Violence, Adriana Cavarero Scales of Justice: Reimagining Political Space in a Globalizing World, Nancy Fraser Pathologies of Reason: On the Legacy of Critical Theory, Axel Honneth States Without Nations: Citizenship for Mortals, Jacqueline Stevens The Racial Discourses of Life Philosophy: Négritude, Vitalism, and Modernity, Donna V. Jones Democracy in What State?, Giorgio Agamben, Alain Badiou, Daniel Bensaïd, Wendy Brown, Jean-Luc Nancy, Jacques Rancière, Kristin Ross, Slavoj Žižek Politics of Culture and the Spirit of Critique: Dialogues, edited by Gabriel Rockhill and Alfredo Gomez-Muller Mute Speech: Literature, Critical Theory, and -

Schriftenverzeichnis Von Mattias Iser

Curriculum Vitae Mattias Iser October 2019 Binghamton University, State University of New York Department of Philosophy Binghamton, NY 13902-6000 Library Tower 1213 607-777-3492 [email protected] www.mattias-iser.com Academic Appointments 09/2016 – Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy, Binghamton University, State University of New York (SUNY) 09/2014 – 09/2016 Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, Binghamton University, State University of New York (SUNY) 12/2009 – 08/2014 Permanent Research Fellow & Member of the Board of Directors, Center for Advanced Studies “Justitia Amplificata: Rethinking Justice – Applied and Global,” Goethe University Frankfurt Spring 2014 Visiting Professor, Department of Philosophy, Karl Franzens- University Graz Spring 2013 Visiting Professor, Department of Philosophy, Karl Franzens- University Graz 03/2012 Visiting Scholar, Department of Philosophy, Karl Franzens- University Graz; invited by Lukas H. Meyer 02/2011 – 04/2011 Visiting Scholar, Department of Philosophy, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA); invited by Barbara Herman 08/2009 – 10/2009 Visiting Scholar, Department of Philosophy, New York University; invited by Thomas Nagel 08/2005 – 12/2005 Theodor Heuss-Lecturer (Visiting Assistant Professor), New School for Social Research, New York 04/2005 – 11/2009 Junior Faculty for political theory and philosophy, Faculty of the Social Sciences, Goethe-University Frankfurt 10/2003 Visiting Lecturer, Higher School of Economics, Moscow 04/1999 – 03/2005 Pre-doctoral teaching position for political theory and philosophy, Faculty of the Social Sciences, Freie Universität Berlin Education 03/2005 Dr. phil., Freie Universität Berlin (grade: Summa cum laude – best possible grade) 12/2003 M.A. (philosophy), Freie Universität Berlin (grade: 1,0 – best possible grade between 1,0 and 6,0) 12/1998 M.A. -

Brian Milstein

BRIAN MILSTEIN work: Exzellenzcluster “Normative Orders” Goethe-Universität Frankfurt HausPostfach EXC 14 60629 Frankfurt am Main, Germany http://www.brianmilstein.com email: [email protected] Academic Employment RESEARCH ASSOCIATE AND LECTURER (Wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter), Chair of International Political Theory, Excellenzcluster “Normative Orders,” Goethe- Universität Frankfurt, SePtember 2016 to present POSTDOCTORAL FELLOW, Leibniz Research GrouP and Excellenzcluster “Normative Orders,” Goethe-Universität Frankfurt, January 2015 to SePtember 2016 POSTDOCTORAL FELLOW, Collège d’études mondiales, Fondation Maison des sciences de l’homme, Paris, January to December 2014 POSTDOCTORAL FELLOW, Forschungskolleg Humanwissenschaften, Goethe-Universität Frankfurt, January to December 2013 POSTDOCTORAL FELLOW, Einstein Foundation WorkgrouP on “Crisis of Democracy,” John-F.-Kennedy Institut für Nordamerikastudien, Freie Universität Berlin, May 2011 to December 2012 ADJUNCT INSTRUCTOR, DePartment of Humanities, New School for Public Engagement, SePtember 2006 to May 2008 Education PH.D. (POLITICS), New School for Social Research, 2011 Major field: Political Theory Minor field: ComParative Politics Cumulative GPA: 3.97 (on 4.00 scale) Dissertation: “Commercium: Toward a Critical Social Theory of the Cosmopolitan” § Selected for the 2011 Hannah Arendt Award in Politics § Nominated for the APSA 2012 Leo Strauss Award Dissertation committee: Nancy Fraser (chair), Andreas Kalyvas, Richard J. bernstein, Rainer Forst, Terry Williams (dean’s rePresentative) M.A. (POLITICS), New School for Social Research, 2003 Selected for the 2003 Outstanding M.A. Graduate Award, Politics A.b. (POLITICAL SCIENCE), Vassar College, 1999 Page 1 of 8 BRIAN MILSTEIN Books (as author) Commercium: Critical Theory from a Cosmopolitan Point of View. London: Rowman & Littlefield International, 2015 § Preface by Nancy Fraser § Back-cover endorsements by William E.