Geography of a Massacre: Cherokee and Carolinian Visions of Land at Long Cane

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cherokee Ethnogenesis in Southwestern North Carolina

The following chapter is from: The Archaeology of North Carolina: Three Archaeological Symposia Charles R. Ewen – Co-Editor Thomas R. Whyte – Co-Editor R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr. – Co-Editor North Carolina Archaeological Council Publication Number 30 2011 Available online at: http://www.rla.unc.edu/NCAC/Publications/NCAC30/index.html CHEROKEE ETHNOGENESIS IN SOUTHWESTERN NORTH CAROLINA Christopher B. Rodning Dozens of Cherokee towns dotted the river valleys of the Appalachian Summit province in southwestern North Carolina during the eighteenth century (Figure 16-1; Dickens 1967, 1978, 1979; Perdue 1998; Persico 1979; Shumate et al. 2005; Smith 1979). What developments led to the formation of these Cherokee towns? Of course, native people had been living in the Appalachian Summit for thousands of years, through the Paleoindian, Archaic, Woodland, and Mississippi periods (Dickens 1976; Keel 1976; Purrington 1983; Ward and Davis 1999). What are the archaeological correlates of Cherokee culture, when are they visible archaeologically, and what can archaeology contribute to knowledge of the origins and development of Cherokee culture in southwestern North Carolina? Archaeologists, myself included, have often focused on the characteristics of pottery and other artifacts as clues about the development of Cherokee culture, which is a valid approach, but not the only approach (Dickens 1978, 1979, 1986; Hally 1986; Riggs and Rodning 2002; Rodning 2008; Schroedl 1986a; Wilson and Rodning 2002). In this paper (see also Rodning 2009a, 2010a, 2011b), I focus on the development of Cherokee towns and townhouses. Given the significance of towns and town affiliations to Cherokee identity and landscape during the 1700s (Boulware 2011; Chambers 2010; Smith 1979), I suggest that tracing the development of towns and townhouses helps us understand Cherokee ethnogenesis, more generally. -

Whispers from the Past

Whispers from the Past Overview Native Americans have been inhabitants of South Carolina for more than 15,000 years. These people contributed in countless ways to the state we call home. The students will be introduced to different time periods in the history of Native Americans and then focus on the Cherokee Nation. Connection to the Curriculum Language Arts, Geography, United States History, and South Carolina History South Carolina Social Studies Standards 8-1.1 Summarize the culture, political systems, and daily life of the Native Americans of the Eastern Woodlands, including their methods of hunting and farming, their use of natural resources and geographic features, and their relationships with other nations. 8-1.2 Categorize events according to the ways they improved or worsened relations between Native Americans and European settlers, including alliances and land agreements between the English and the Catawba, Cherokee, and Yemassee; deerskin trading; the Yemassee War; and the Cherokee War. Social Studies Literacy Elements F. Ask geographic questions: Where is it located? Why is it there? What is significant about its location? How is its location related to that of other people, places, and environments? I. Use maps to observe and interpret geographic information and relationships P. Locate, gather, and process information from a variety of primary and secondary sources including maps S. Interpret and synthesize information obtained from a variety of sources—graphs, charts, tables, diagrams, texts, photographs, documents, and interviews Time One to two fifty-minute class periods Materials South Carolina: An Atlas Computer South Carolina Interactive Geography (SCIG) CD-ROM Handouts included with lesson plan South Carolina Highway Map Dry erase marker Objectives 1. -

Cherokee Archaeological Landscapes As Community Action

CHEROKEE ARCHAEOLOGICAL LANDSCAPES AS COMMUNITY ACTION Paisagens arqueológicas Cherokee como ação comunitária Kathryn Sampeck* Johi D. Griffin Jr.** ABSTRACT An ongoing, partnered program of research and education by the authors and other members of the Tribal Historic Preservation Office of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians contributes to economic development, education, and the creation of identities and communities. Landscape archaeology reveals how Cherokees navigated the pivotal and tumultuous 16th through early 18th centuries, a past muted or silenced in current education programs and history books. From a Cherokee perspective, our starting points are the principles of gadugi, which translates as “town” or “community,” and tohi, which translates as “balance.” Gadugi and tohi together are cornerstones of Cherokee identity. These seemingly abstract principles are archaeologically detectible: gadugi is well addressed by understanding the spatial relationships of the internal organization of the community; the network of relationships among towns and regional resources; artifact and ecofact traces of activities; and large-scale “non-site” features, such as roads and agricultural fields. We focus our research on a poorly understood but pivotal time in history: colonial encounters of the 16th through early 18th centuries. Archaeology plays a critical role in social justice and ethics in cultural landscape management by providing equitable access by * Associate Professor, Illinois State University, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Campus Box 4660, Normal, IL 61701. E-mail: [email protected] ** Historic Sites Keeper, Tribal Historic Preservation Office, Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Qualla Boundary Reservation, P.O. Box 455, Cherokee, NC 28719, USA. História: Questões & Debates, Curitiba, volume 66, n.2, p. -

EARTH MOTHER CRYING: Encyclopedia of Prophecies of Peoples of The

EARTH MOTHER CRYING: Encyclopedia of Prophecies of Peoples of the Western Hemisphere, , , PART TWO of "The PROPHECYKEEPERS" TRILOGY , , Proceeds from this e-Book will eventually provide costly human translation of these prophecies into Asian Languages NORTH, , SOUTH , & CENTRAL , AMERICAN , INDIAN;, PACIFIC ISLANDER; , and AUSTRALIAN , ABORIGINAL , PROPHECIES, FROM "A" TO "Z" , Edited by Will Anderson, "BlueOtter" , , Compilation © 2001-4 , Will Anderson, Cabool, Missouri, USA , , Wallace "Mad Bear" Anderson, "I am Mad Bear Anderson, and I 'walked west' in Founder of the American Indian Unity 1985. Doug Boyd wrote a book about me, Mad Bear : Movement , Spirit, Healing, and the Sacred in the Life of a Native American Medicine Man, that you might want to read. Anyhow, back in the 50s and 60s I traveled all over the Western hemisphere as a merchant seaman, and made contacts that eventually led to this current Indian Unity Movement. I always wanted to write a book like this, comparing prophecies from all over the world. The elders have always been so worried that the people of the world would wake up too late to be ready for the , events that will be happening in the last days, what the Thank You... , Hopi friends call "Purification Day." Thanks for financially supporting this lifesaving work by purchasing this e-Book." , , Our website is translated into many different languages by machine translation, which is only 55% accurate, and not reliable enough to transmit the actual meaning of these prophecies. So, please help fulfill the prophecy made by the Six Nations Iroquois Lord of the Confederacy or "Sachem" Wallace "Mad Bear" Anderson -- Medicine Man to the Tuscaroras, and founder of the modern Indian Unity Movement -- by further supporting the actual human translation of these worldwide prophecy comparisons into all possible languages by making a donation, or by purchasing Book #1. -

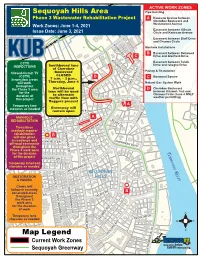

Sequoyah Hills Area Map Legend

NORTH BELLEMEADE AVE ACTIVE WORK ZONES Sequoyah Hills Area Pipe-bursting Phase 3 Wastewater Rehabilitation Project A Kenesaw Avenue between Cherokee Boulevard and Work Zones: June 1-4, 2021 Westerwood Avenue Easement between Hillvale Issue Date: June 3, 2021 KINGSTON PIKE Circle and Kenesaw Avenue Easement between Bluff Drive and Cheowa Circle BOXWOOD SQ Manhole Installations B Easement between Dellwood C Drive and Glenfield Drive KITUWAH TRL CCTV Easement between Talahi Southbound lane Drive and Iskagna Drive INSPECTIONS EAST HILLVALE TURN of Cherokee Paving & Restoration Closed-Circuit TV BoulevardWEST HILLVALE TURN CLOSED (CCTV) D C Boxwood Square Inspection crews 7 a.m. – 3 p.m., will work Thursday, June 4 Natural Gas System Work throughout LAKE VIEW DR the Phase 3 area Northbound D Cherokee Boulevard for the lane will be used between Kituwah Trail and to alternate Cheowa Circle (June 4 ONLY duration of weather permitting) this project traffic flow with flaggers present Temporary lane A closures as needed WOODHILLGreenway PL will remain openHILLVALE CIR MANHOLE A BLUFF DR REHABILITATION CHEOWA CIR Trenchless DELLWOOD DR manhole repairs/ OAKHURST DR KENESAW AVE TOWANDArehabilitation TRL B will take place in roadwaysSCENIC DR and GLENFIELD DR CHEROKEE BLVD off-road easements throughout the Phase 3 work zone Tennessee River for the duration of this project KENILWORTH DR Temporary lane/road closures as needed ALTA VISTA WAY WINDGATE ST ISKAGNA DR WOODLAND DR SEQUOYAH RESTORATION HILLS & PAVING Crews will EAST NOKOMIS CIR follow in recently B excavated areas WEST NOKOMIS CIR throughoutSAGWA DR TALAHI DR the Phase 3 work area SOUTHGATE RD for the duration of work KENESAW AVE TemporaryBLUFF VIEW RD lane closures as needed KEOWEE AVE TUGALOO DR W E S Map LegendAGAWELA AVE TALILUNA AVE Current Work Zones Sequoyah Greenway CHEROKEE BLVD. -

The Relations of the Cherokee Indians with the English in America Prior to 1763

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-1923 The Relations of the Cherokee Indians with the English in America Prior to 1763 David P. Buchanan University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Buchanan, David P., "The Relations of the Cherokee Indians with the English in America Prior to 1763. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 1923. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/98 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by David P. Buchanan entitled "The Relations of the Cherokee Indians with the English in America Prior to 1763." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in . , Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: ARRAY(0x7f7024cfef58) Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) THE RELATIONS OF THE CHEROKEE Il.J'DIAUS WITH THE ENGLISH IN AMERICA PRIOR TO 1763. -

The Savannah River System L STEVENS CR

The upper reaches of the Bald Eagle river cut through Tallulah Gorge. LAKE TOXAWAY MIDDLE FORK The Seneca and Tugaloo Rivers come together near Hartwell, Georgia CASHIERS SAPPHIRE 0AKLAND TOXAWAY R. to form the Savannah River. From that point, the Savannah flows 300 GRIMSHAWES miles southeasterly to the Atlantic Ocean. The Watershed ROCK BOTTOM A ridge of high ground borders Fly fishermen catch trout on the every river system. This ridge Chattooga and Tallulah Rivers, COLLECTING encloses what is called a EASTATOE CR. SATOLAH tributaries of the Savannah in SYSTEM watershed. Beyond the ridge, LAKE Northeast Georgia. all water flows into another river RABUN BALD SUNSET JOCASSEE JOCASSEE system. Just as water in a bowl flows downward to a common MOUNTAIN CITY destination, all rivers, creeks, KEOWEE RIVER streams, ponds, lakes, wetlands SALEM and other types of water bodies TALLULAH R. CLAYTON PICKENS TAMASSEE in a watershed drain into the MOUNTAIN REST WOLF CR. river system. A watershed creates LAKE BURTON TIGER STEKOA CR. a natural community where CHATTOOGA RIVER ARIAIL every living thing has something WHETSTONE TRANSPORTING WILEY EASLEY SYSTEM in common – the source and SEED LAKEMONT SIX MILE LAKE GOLDEN CR. final disposition of their water. LAKE RABUN LONG CREEK LIBERTY CATEECHEE TALLULAH CHAUGA R. WALHALLA LAKE Tributary Network FALLS KEOWEE NORRIS One of the most surprising characteristics TUGALOO WEST UNION SIXMILE CR. DISPERSING LAKE of a river system is the intricate tributary SYSTEM COURTENAY NEWRY CENTRALEIGHTEENMILE CR. network that makes up the collecting YONAH TWELVEMILE CR. system. This detail does not show the TURNERVILLE LAKE RICHLAND UTICA A River System entire network, only a tiny portion of it. -

NINETY SIX to ABOUT YOUR VISIT Ninety Six Was Designated a National Historic National Historic Site • S.C

NINETY SIX To ABOUT YOUR VISIT Ninety Six was designated a national historic National Historic Site • S.C. site on August 16, 1976. While there Is much archaeological and historical study, planning and INDIANS AND COLONIAL TRAVELERS, A development yet to be done In this new area of CAMPSITE ON THE CHEROKEE PATH the National Park System, we welcome you to Ninety Six and Invite you to enjoy the activities which are now available. FRONTIER SETTLERS, A REGION OF RICH This powder horn is illustrated with the only known LAND, A TRADING CENTER AND A FORT map of Lieutenant Colonel Grant's 1761 campaign The mile-long Interpretive trail takes about FOR PROTECTION AGAINST INDIAN against the Cherokees. Although it is unsigned, the one hour to walk and Includes several strenuous ATTACK elaborate detail and accuracy of the engraving indicate that the powder horn was inscribed by a soldier, grades. The earthworks and archaeological probably an officer, who marched with the expedition. remains here are fragile. Please do not disturb or damage them. RESIDENTS OF THE NINETY SIX DISTRICT, A Grant, leading a force of 2,800 regular and provincial COURTHOUSE AND JAIL FOR THE ADMINI troops, marched from Charlestown northwestward along The site abounds In animal and plant life, STRATION OF JUSTICE the Cherokee Path to attack the Indian towns. An including poisonous snakes, poison oak and Ivy. advanced supply base was established at Ninety Six. We suggest that you stay on the trail. The Grant campaign destroyed 15 villages in June and July, 1761. This operation forced the Cherokees to sue The Ninety Six National Historic Site Is located PATRIOTS AND LOYALISTS IN THE REVOLU for peace, thus ending the French and Indian War on the on Highway S.C. -

To Jocassee Gorges Trust Fund

Jocassee Journal Information and News about the Jocassee Gorges Summer/Fall, 2000 Volume 1, Number 2 Developer donates $100,000 to Jocassee Gorges Trust Fund Upstate South Carolina developer Jim Anthony - whose things at Jocassee with the interest from development Cliffs at Keowee Vineyards is adjacent to the Jocassee the Trust Fund. Gorges - recently donated $100,000 to the Jocassee Gorges Trust “We are excited about Cliffs Fund. Communities becoming a partner with the “The job that the conservation community has done at Jocassee DNR on the Jocassee project,” Frampton Gorges has really inspired me,” said Anthony, president of Cliffs said. “Although there is a substantial Communities. “It’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to be here at amount of acreage protected in the the right time and to be able to help like this. We’re delighted to Jocassee Gorges, some development play a small part in maintaining the Jocassee Gorges tract.” around it is going to occur. The citizens John Frampton, assistant director for development and national in this state are fortunate to have a affairs with the S.C. Department of Natural Resources, said developer like Jim Anthony whose Anthony’s donation will “jump-start the Trust Fund. This will be a conservation ethic is reflected in his living gift, because we will eventually be able to do many good properties. In the Cliffs Communities’ developments, a lot of the green space and key wildlife portions are preserved and enhanced. Jim Anthony has long been known as a conservationist, and this generous donation further illustrates his commitment to conservation and protection of these unique mountain habitats.” Approved in 1997 by the S.C. -

Jocassee Journal Information and News About the Jocassee Gorges

Jocassee Journal Information and News about the Jocassee Gorges www.dnr.sc.gov Fall/Winter 2020 Volume 21, Number 2 Wildflower sites in Jocassee Gorges were made possible by special funding from Duke Energy’s Habitat Enhancement Program. (SCDNR photo by Greg Lucas) Duke Energy funds colorful Jocassee pollinator plants Insects and hummingbirds South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR) Jocassee Gorges Project Manager Mark Hall flocked to wildflower sites approached the HEP committee in 2019 with a proposal Several places within the Jocassee Gorges received a to establish wildflower patches throughout Jocassee Gorges colorful “facelift” in 2020, thanks to special funding through to benefit “pollinator species.” Pollinator species include Duke Energy’s Habitat Enhancement Program (HEP). bats, hummingbirds, bees, butterflies and As part of the Keowee-Toxaway relicensing other invertebrates that visit wildflowers and agreement related to Lakes Jocassee and Keowee, subsequently distribute pollen among a wide Duke Energy collects fees associated with docks range of fruit-bearing and seed-bearing plants. and distributes the monies each year for projects The fruits and seeds produced are eventually consumed within the respective watersheds to promote wildlife habitat by a host of game and non-game animals. Pollinator species improvements. Continued on page 2 Mark Hall, Jocassee Gorges Project land manager, admires some of the pollinator species that were planted in Jocassee Gorges earlier this year. (SCDNR photo by Cindy Thompson) Jocassee wildflower sites buzzing with life Continued from page 1 play a key role in the complex, ecological chain that is the is a very important endeavor. Several additional miles of foundation for diverse vegetation within Jocassee Gorges. -

Descendants of Smallpox Conjurer of Tellico

Descendants of Smallpox Conjurer of Tellico Generation 1 1. SMALLPOX CONJURER OF1 TELLICO . He died date Unknown. He married (1) AGANUNITSI MOYTOY. She was born about 1681. She died about 1758 in Cherokee, North Carolina, USA. He married (2) APRIL TKIKAMI HOP TURKEY. She was born in 1690 in Chota, City of Refuge, Cherokee Nation, Tennessee, USA. She died in 1744 in Upper Hiwasssee, Tennessee, USA. Smallpox Conjurer of Tellico and Aganunitsi Moytoy had the following children: 2. i. OSTENACO "OUTACITE" "USTANAKWA" "USTENAKA" "BIG HEAD" "MANKILLER OF KEOWEE" "SKIAGUSTA" "MANKILLER" "UTSIDIHI" "JUDD'S FRIEND was born in 1703. He died in 1780. 3. ii. KITEGISTA SKALIOSKEN was born about 1708 in Cherokee Nation East, Chota, Tennessee, USA. He died on 30 Sep 1792 in Buchanan's Station, Tennessee, Cherokee Nation East. He married (1) ANAWAILKA. She was born in Cherokee Nation East, Tennessee, USA. He married (2) USTEENOKOBAGAN. She was born about 1720 in Cherokee Nation East, Chota, Tennessee, USA. She died date Unknown. Notes for April Tkikami Hop Turkey: When April "Tikami" Hop was 3 years old her parents were murdered by Catawaba Raiders, and her and her 4 siblings were left there to die, because no one, would take them in. Pigeon Moytoy her aunt's husband, heard about this and went to Hiawassee and brought the children home to raise in the Cherokee Nation ( he was the Emperor of the Cherokee Nation, and also related to Cornstalk through his mother and his wife ). Visit WWW. My Carpenter Genealogy Smallpox Conjurer of Tellico and April Tkikami Hop Turkey had the following child: 4. -

Georgia Genealogy Research Websites Note: Look for the Genweb and Genealogy Trails of the County in Which Your Ancestor Lived

Genealogy Research in Georgia Early Native Americans in Georgia Native inhabitants of the area that is now Georgia included: *The Apalachee Indians *The Cherokee Indians *The Hitchiti, Oconee and Miccosukee Indians *The Muskogee Creek Indians *The Timucua Indians *The Yamasee and Guale Indians In the late 1700’s and early 1800’s, most of these tribes were forced to cede their land to the U.S. government. The members of the tribes were “removed” to federal reservations in the western U.S. In the late 1830’s, remaining members of the Cherokee tribes were forced to move to Oklahoma in what has become known as the “Trail of Tears.” Read more information about Native Americans of Georgia: http://www.native-languages.org/georgia.htm http://www.ourgeorgiahistory.com/indians/ http://www.aboutnorthgeorgia.com/ang/American_Indians_of_Georgia Some native people remained in hiding in Georgia. Today, the State of Georgia recognizes the three organizations of descendants of these people: The Cherokee Indians of Georgia: PO Box 337 St. George, GA 31646 The Georgia Tribe of Eastern Cherokee: PO Box 1993, Dahlonega, Georgia 30533 or PO Box 1915, Cumming, GA 30028 http://www.georgiatribeofeasterncherokee.com/ The Lower Muscogee Creek Tribe: Rte 2, PO Box 370 Whigham, GA 31797 First People - Links to State Recognized Tribes, sorted by state - http://www.firstpeople.us/FP-Html-Links/state- recognized-tribes-in-usa-by-state.html European Settlement of Georgia Photo at left shows James Oglethorpe landing in what is now called Georgia 1732: King George II of England granted a charter to James Oglethorpe for the colony of Georgia to be a place of refuge.