Comparative Study of Equity Accounting in the United States and the United Kingdom from a Generally Accepted Accounting Practices Viewpoint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lagged and Contemporaneous Reserve Accounting: an Alternative View

Lagged and Contemporaneous Reserve Accounting: An Alternative View DANIEL L. THORNTON Recently, Feige and McGee presented evidence ECENT volatility in both money and interest that the effect of LEA on federal funds rate volatility has not been substantial when week-to-week relative rates has prompted the Federal Reserve Board to 3 adopt a plan for contemporaneous reserve accounting changes are considered. Thus, previous empirical 1 (CRA). This move follows a number of requests from work on the volatility of short-term imiterest rates under both insideand outside the Federal Reserve System to LEA, which considered longer time periods or abso- return to CRA. These requests stem from empirical lute measures of variability, may be misleading. This investigations that show that both money and interest article presents a theoretical argument to further sup- rates hecame more volatile after the adoption of lagged port this conclusion. It should be emphasized that only reserve accounting (LEA) in September 1968, and the case ofa move from CRA to LEA is considered, hut from theoretical work that shows an increase in volatil- the premise applies equally well to the return to CRA. ity of money and possibly interest rates when the Sys- 2 The outlimie of the article is as follows: First, the tem moves from CRA to LEA. rationale for claiming that the case against LEA is overstated is presented. This idea is then formalized in the context of a simple linear stochastic model of the Daniel L. Thornton is a senior economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. John G. -

Operating Reserve: How and Why

Operating Reserve: How and Why Although most nonprofit organizations know that an Operating Reserve is essential, not everyone succeeds in TREC Financial Management Resource Management Financial TREC building one and keeping it. This resource walks through the common obstacles to creating an Operating Reserve and lays out a clear path to achieve it. Definition and Terminology An Operating Reserve is an unrestricted fund balance that is set aside by a nonprofit to assist through unforeseen challenges, help with cash flow shortfalls, and take advantage of unexpected opportunities. In simpler terms, it is a type of savings. An Operating Reserve is sometimes simply referred to as a Reserve Fund. Both of these names are correct. A Reserve Fund is the broader category. Reserve Funds may be split up and named differently on the Statement of Financial Position (Balance Sheet) based upon the intent of the Reserve. For the purposes of this Resource we are using the term Operating Reserve due to its prevalence of use in the nonprofit field and the intended purpose of the fund. After an adequate Operating Reserve is built, other reserve funds can be added. We will discuss different types of reserves further below. Be careful not to confuse net assets with reserves. The balance in the bank accounts is not the same as the reserves. Those balances may include unspent grant money. A reserve is only made up of unrestricted funds and should be explicitly broken out in the equity section of the Statement of Financial Position separate from funds with donor restrictions. Why Have an Operating Reserve Without a clear understanding of why an Operating Reserve benefits the organization, building the will and desire to create one is near impossible. -

Economic Brief March 2012, EB12-03

Economic Brief March 2012, EB12-03 Loan Loss Reserve Accounting and Bank Behavior By Eliana Balla, Morgan J. Rose, and Jessie Romero The rules governing banks’ loan loss provisioning and reserves require a trade-off between the goals of bank regulators, who emphasize safety and soundness, and the goals of accounting standard setters, who emphasize the transparency of fi nancial statements. A strengthening of accounting priorities in the decade prior to the fi nancial crisis was associated with a decrease in the level of loan loss reserves in the banking system. The recent fi nancial crisis has prompted an bank’s fi nancial statements: the balance sheet evaluation of many aspects of banks’ fi nancing (Figure 1) and the income statement (Figure 2).2 and accounting practices. One area of renewed Outstanding loans are recorded on the asset interest is the appropriate level of loan loss side of a bank’s balance sheet. The loan loss reserves, the money banks set aside to off set reserves account is a “contra-asset” account, future losses on outstanding loans.1 Deter- which reduces the loans by the amount the mining that level depends on balancing the bank’s managers expect to lose when some requirements of bank regulators, who empha- portion of the loans are not repaid. Periodically, size the importance of loan loss reserves to the bank’s managers decide how much to add protect the safety and soundness of the bank, to the loan loss reserves account, and charge and of accounting regulators, who emphasize this amount against the bank’s current earnings. -

RESERVE STUDY GUIDELINES for Homeowner Association Budgets

State of California Department of Real Estate RESERVE STUDY GUIDELINES for Homeowner Association Budgets August 2010 State of California Department of Real Estate RESERVE STUDY GUIDELINES for Homeowner Association Budgets August 2010 This independent research report was developed under contract for the California Department of Real Estate by Eva Eagle, Ph.D., and Susan Stoddard, Ph.D., AICP, Institute for the Study of Family, Work and Community and David H. Levy, M.B.A., C.P.A. Janet Andrews, MBA, was responsible for the original design, layout, and typography. The Department of Real Estate revised this publication in August 2010. It includes updates by Roy Helsing PRA, RS to insure it aligns with current California Law and the guidelines of the Association of Professional Reserve Preparers (APRA) and the Community Associations Institute (CAI).,” The report does not necessarily reflect the position of the Administration of the State of California. NOTE: Before a homeowners’ association decides to prepare its own Reserve Study, it should consider seeking professional advice on that issue. There are issues concerning volunteer board member indemnification, reliance on expert advice, and other factors that should be considered in that decision. The goal of this manual is to help the reader better understand Reserve Studies. It is not the intent of this manual to define the “standard of care” for Reserve Studies or to interpret the California Civil Code. Department of Real Estate . Publications . 2201 Broadway . Sacramento, CA 95818 . Web -

Asset Equipment & Building Reserves

Asset Equipment & Building Reserves MANAGING EQUIPMENT REPLACEMENT AND MAJOR BUILDING MAINTENANCE 6/27/2016 BUSINESS SERVICES 1 Introduction •Changes within the State system of accounting practices have changed the way institution will be accounting for equipment and building reserves going forward. SOU will be beginning with initial implementation in FY2017. •The will be a period of transition from the old model to the new model, after which, the Renewal & Replacement Fund group will be largely phased out. 10/24/2016 BUSINESS SERVICES 2 Agenda •Overview •Definitions •Previous OUS Model. •Previous SOU Modified Model •New SOU Model •Review of Transaction Process using the new SOU Model •Summary 10/24/2016 BUSINESS SERVICES 3 Overview •With the independence of the universities within the State university system, comes with it the ability to make changes to accounting structures. There is still some degree of relationships within the base Fund Structures from university to university, primarily to aid in the preparation of comparable financial statement between universities within the state. •One change occurring between all universities is the phasing out of the Renewal and Replacement Funds. These were largely used to establish reserves for equipment and building maintenance reserves. These will be migrated back to the Current Operating Fund group, as the R&R Fund group is phased out. This document will show the steps that will be taken to accommodate the transition to the new accounting structure for Major Equipment Reserves, and Major Building Replacement Reserves. 10/24/2016 BUSINESS SERVICES 4 Definitions Proprietary Funds = “Unrestricted” funds within Auxiliaries, and Service Centers Non-proprietary Funds = All other funds Major Equipment = Items > $5,000, and a useful life of two years or more. -

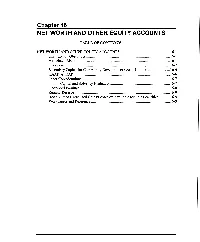

Chapter 16 NET WORTH and OTHER EQUITY ACCOUNTS

Chapter 16 NET WORTH AND OTHER EQUITY ACCOUNTS TABLE OF CONTENTS NET WORTH AND OTHER EQUITY ACCOUNTS .................................................... 16. 1 Examination Objectives ....................................................................................... 16-1 Associated Risks .................................................................................................. 16. 1 Overview ............................................................................................................. .1 6.2 Secondary Capital for Community Development Credit Unions ....................... 16-4 GAAP vs . RAP .................................................................................................... 16-6 Other Considerations ........................................................................................... 16-7 Capital and Solvency Evaluation ............................................................. 16.7 Undivided Earnings ............................................................................................. 16-8 Regular Reserve .................................................................................................... 6-9 Accumulated Unrealized GainsLosses on Available for Sale Securities............ 16-9 Workpapers and References................................................................................. 16-9 Chapter 16 NET WORTH AND OTHER EQUITY ACCOUNTS Examination 0 Determine whether the credit union complies with Regulation D, Objectives if applicable 0 Ascertain compliance with -

Reserves, Liquidity and Money: an Assessment of Balance Sheet Policies1

Reserves, liquidity and money: 1 an assessment of balance sheet policies Jagjit S Chadha,2 Luisa Corrado3 and Jack Meaning4 Abstract The financial crisis and its aftermath have stimulated a vigorous debate on the use of macro- prudential instruments both for regulating the banking system and for providing additional tools for monetary policymakers. The widespread adoption of non-conventional monetary policies has provided some evidence on the efficacy of liquidity and asset purchases for offsetting the zero lower bound. Central banks have thus been put in mind of the effectiveness of extended open market operations as supplementary monetary policy tools. These are essentially fiscal instruments, in that they entail the issuance of central bank liabilities backed by fiscal transfers. Given that these tools are written into fiscal budget constraints, we can examine the consequences of the operations in the context of a micro- founded macroeconomic model of banking and money, and we can simulate the responses of the Federal Reserve balance sheet to the crisis. Specifically, we examine the role that reserves for bond and capital swaps play in stabilising the economy, as well as the impact of changes in the composition of the central bank balance sheet. We find that such policies can significantly enhance the ability of the central bank to stabilise the economy. This is because balance sheet operations supply (remove) liquidity to a financial market that is otherwise short (long) of liquidity, and hence allow other financial spreads to move less violently over the cycle to compensate. Keywords: Non-conventional monetary interest on reserves, monetary and fiscal policy instruments, Basel III JEL classification: E31, E40, E51 1 This version of the paper dates from December 2011. -

Report on Matters Identified at Strategic Petroleum Reserve

This document is an ASCII-formatted version of a printed document. The page numbers in this electronic version may not be in the same order as those in the printed document. The printed document may also contain charts and photographs which are not reproduced in this electronic version. If you require the printed version of this document, contact the Office of Inspector General (IG-1), Department of Energy, 1000 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC, 20585, or call the Office of Inspector General Reports Request Line at (202) 586-2744. U. S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL REPORT ON MATTERS IDENTIFIED AT THE STRATEGIC PETROLEUM RESERVE DURING THE AUDIT OF THE DEPARTMENT'S CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION AS OF SEPTEMBER 30, 1995 The Office of Audit Services wants to make the distribution of its audit reports as customer friendly and cost effective as possible. Therefore, this report will be available electroncially through the Internet 5 to 7 days after publication at the following alternative addresses: Department of Energy Headquarters Gopher gopher.hr.doe.gov Department of Energy Headquarters Anonymous FTP vm1.hqadmin.doe.gov We are experimenting with various options to facilitate audit report distribution. Your comments would be appreciated and can be provided on the Customer Comment Form attached to the Audit Report. Report Number: CR-FS-96-03 Capital Regional Audit Office Date of Issue: April 15, 1996 Germantown, MD 20874 REPORT ON MATTERS IDENTIFIED AT THE STRATEGIC PETROLEUM RESERVE DURING THE AUDIT OF THE DEPARTMENT'S CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION AS OF SEPTEMBER 30, 1995 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page SUMMARY ........ -

Preparing Budgets and Reserve Schedules

DIVISION OF FLORIDA CONDOMINIUMS, TIMESHARES, AND MOBILE HOMES DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS AND PROFESSIONAL REGULATION BUDGETS & RESERVE SCHEDULES A Self-Study Training Manual 2601 Blair Stone Road , TALLAHASSEE, FLORIDA 32399-1031 Budgets & Reserve Schedules A Self-Study Training Manual PUBLISHED BY THE Department of Business and Professional Regulation Division of Florida Condominiums, Timeshares, and Mobile Homes 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS FIGURES & TABLES..............................................................................................................................................5 PREFACE....................................................................................................................................................................6 1 GETTING STARTED ..............................................................................................................................................8 WHY DO ASSOCIATIONS HAVE A BUDGET?.............................................................................................................8 WHEN TO BEGIN THE BUDGETING PROCESS ...........................................................................................................8 MEETINGS HELD WHILE DEVELOPING THE BUDGET ................................................................................................8 SAMPLE NOTICES ......................................................................................................................................................9 ABOUT ACCOUNTING RECORDS ...............................................................................................................................9 -

Reserve Funds

Office of the New York State Comptroller Division of Local Government and School Accountability LOCAL GOVERNMENT MANAGEMENT GUIDE Reserve Funds Thomas P. DiNapoli State Comptroller For additional copies of this report contact: Division of Local Government and School Accountability 110 State Street, 12th floor Albany, New York 12236 Tel: (518) 474- 4037 Fax: (518) 486- 6479 or email us: [email protected] RMD53_2009 www.osc.state.ny.us January 2010 Table of Contents Intended Use of Reserves ................................................................................................... 2 Board Direction and Oversight ........................................................................................... 3 Visibility of Reserve Fund Transactions ................................................................................ 4 Investment of Reserve Funds .............................................................................................. 4 Reserve Fund Accounting Records and Reports ................................................................... 5 Reserves Authorized By The General Municipal Law (GML) .................................................. 6 Capital Reserve Fund ..................................................................................................... 6 Repair Reserve Fund .....................................................................................................11 Contingency and Tax Stabilization Reserve Fund ............................................................12 Snow -

Basic Insurance Accounting—Selected Topics

Basic Insurance Accounting – Selected Topics By Ralph S. Blanchard III, FCAS, MAAA 1 July 2008 CAS Study Note Author’s Change to This Edition This edition of the study note is the same as the June 2007 edition except for the following change to the third paragraph of section 8 on page 23: “Under GAAP all the newly purchased and identified assets and liabilities are to be valued at their “fair value”, with goodwill equal to the difference between the fair value of identified acquired assets and the fair value of identified acquired liabilities” has been changed to “Under GAAP all the newly purchased and identified assets and liabilities are to be valued at their “fair value”, with goodwill equal to the difference between the purchase price and the fair value of identified acquired assets less the fair value of identified acquired liabilities.” Basic Insurance Accounting – Selected Topics The purpose of this study note is to educate actuaries on certain basic insurance accounting topics that may be omitted in other syllabus readings. These topics include: • Loss and loss adjustment expense accounting basics • Reinsurance accounting basics • Examples of how ceded reinsurance impacts an insurers financial statements • Deposit accounting basics In addition, the following two fundamental accounting equations are provided, representing basic equations that may no longer be found in the other syllabus articles but that all actuaries should know. • Assets – Liabilities = Equity (sometimes labeled “net assets” or “surplus”) • Revenue – Expense = Income (with expense including incurred losses and underwriting expenses for an insurance company). (Note: Most accounting systems rely on some form of double-entry bookkeeping, under which all transactions result in debit and credit entries that have to balance. -

AWWA Cash Reserve Policy Guideline

Cash Reserve Policy Guidelines Copyright© 2018 American Water Works Association AWWA RATES & CHARGES COMMITTEE WHITEPAPER Cash Reserve Policy Guidelines INTRODUCTION Public and investor-owned water-resources related utilities (including water, wastewater, stormwater, and reclaimed water systems) must meet the operational, maintenance, and capital needs of a complex system while being financially independent, relying largely on revenue from service charges. Providing utility service requires the investment in, maintenance of, and operation of expensive, complex, and regulated infrastructure. Utility systems have no margin for failure; they are expected to provide uninterrupted service 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Furthermore, many of the assets of a utility are located in hard to reach places (belowground) and are intermingled with other assets (within easements that include other infrastructure). Aging infrastructure is one of the most critical issues facing the water-resources industry. With aging infrastructure of any kind comes increased probability of unplanned failure. Not only are emergency repairs unexpected, but given the nature of an unexpected event, repair costs can be higher than normal maintenance. In addition to the challenge of aging infrastructure, utility revenue is often dependent on weather conditions and thus can be volatile. During periods of high rain fall, water usage and corresponding revenue can decline as irrigation use decreases. In contrast, during drought periods, utilities are often faced with mandatory water restrictions that can have the same negative impact on water use and revenue. As such, cash reserve balances are a critical component to a utility’s financial resiliency and sustainability. Reserve balances for utility systems are funds set aside for a specific cash flow requirement, financial need, project, task, or legal covenant.