Reflections on Reconciliation Within the Georgian Bay Biosphere Region, Anishinabek Territory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Apply

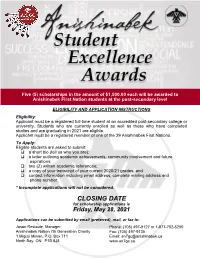

Five (5) scholarships in the amount of $1,500.00 each will be awarded to Anishinabek First Nation students at the post-secondary level ELIGIBILITY AND APPLICATION INSTRUCTIONS Eligibility: Applicant must be a registered full-time student at an accredited post-secondary college or university. Students who are currently enrolled as well as those who have completed studies and are graduating in 2021 are eligible. Applicant must be a registered member of one of the 39 Anishinabek First Nations. To Apply: Eligible students are asked to submit: a short bio (tell us who you are); a letter outlining academic achievements, community involvement and future aspirations; two (2) written academic references; a copy of your transcript of your current 2020/21 grades; and contact information including email address, complete mailing address and phone number. * Incomplete applications will not be considered. CLOSING DATE for scholarship applications is Friday, May 28, 2021 Applications can be submitted by email (preferred), mail, or fax to: Jason Restoule, Manager Phone: (705) 497-9127 or 1-877-702-5200 Anishinabek Nation 7th Generation Charity Fax: (705) 497-9135 1 Migizii Miikan, P.O. Box 711 Email: [email protected] North Bay, ON P1B 8J8 www.an7gc.ca Post-secondary students registered with the following Anishinabek First Nation communities are eligible to apply Aamjiwnaang First Nation Moose Deer Point Alderville First Nation Munsee-Delaware Nation Atikameksheng Anishnawbek Namaygoosisagagun First Nation Aundeck Omni Kaning Nipissing First Nation -

Byng Inlet Water Quality Characterization – 2014-2016

Byng Inlet Water Quality Characterization – 2014-2016 1/10/2017 Prepared for: Magnetawan First Nation Clark 13 Aubrey St., Bracebridge, ON P1L 1M1 705 645 2967 1/10/2017 Anthony LaForge Director of Lands and Resources Magnetawan First Nation 10 Highway 529, Britt, ON P0G 1A0 Dear Mr. LaForge, I am pleased to submit this report which summarizes the water quality monitoring that was conducted on Byng Inlet from 2014 to 2016. This report summarizes the findings of the three-year project. An examination of measured runoff depths and mean Magnetawan P concentrations indicate export coefficients typical of forested watersheds. This means that the Magnetawan River is behaving like a natural river with respect to phosphorus concentrations. Watershed inputs to Byng Inlet from the Magnetawan River are therefore not a concern with respect to phosphorus at this time. These results indicate that although the water quality with respect to nutrients is excellent there are sources of nutrients within the Inlet that contribute to phosphorus loading but these are difficult to assess due to the large volume of dilution water contributed by the Magnetawan River. There has been an effort here to identify the potential sources of phosphorus to Byng Inlet but no effort has been made to quantify the loads from these sources. Variations in the phosphorus concentrations both seasonally and between sample stations tend to vary between years but it should be noted that the magnitude of the variation in P concentrations is slight. In addition, the measured concentrations of total phosphorus indicate excellent water quality relative to Provincial Water Quality Objectives. -

Community Profiles for the Oneca Education And

FIRST NATION COMMUNITY PROFILES 2010 Political/Territorial Facts About This Community Phone Number First Nation and Address Nation and Region Organization or and Fax Number Affiliation (if any) • Census data from 2006 states Aamjiwnaang First that there are 706 residents. Nation • This is a Chippewa (Ojibwe) community located on the (Sarnia) (519) 336‐8410 Anishinabek Nation shores of the St. Clair River near SFNS Sarnia, Ontario. 978 Tashmoo Avenue (Fax) 336‐0382 • There are 253 private dwellings in this community. SARNIA, Ontario (Southwest Region) • The land base is 12.57 square kilometres. N7T 7H5 • Census data from 2006 states that there are 506 residents. Alderville First Nation • This community is located in South‐Central Ontario. It is 11696 Second Line (905) 352‐2011 Anishinabek Nation intersected by County Road 45, and is located on the south side P.O. Box 46 (Fax) 352‐3242 Ogemawahj of Rice Lake and is 30km north of Cobourg. ROSENEATH, Ontario (Southeast Region) • There are 237 private dwellings in this community. K0K 2X0 • The land base is 12.52 square kilometres. COPYRIGHT OF THE ONECA EDUCATION PARTNERSHIPS PROGRAM 1 FIRST NATION COMMUNITY PROFILES 2010 • Census data from 2006 states that there are 406 residents. • This Algonquin community Algonquins of called Pikwàkanagàn is situated Pikwakanagan First on the beautiful shores of the Nation (613) 625‐2800 Bonnechere River and Golden Anishinabek Nation Lake. It is located off of Highway P.O. Box 100 (Fax) 625‐1149 N/A 60 and is 1 1/2 hours west of Ottawa and 1 1/2 hours south of GOLDEN LAKE, Ontario Algonquin Park. -

Anishinabek Nation Governance Agreement at a Glance

The Anishinabek Nation Governance Agreement At a Glance ANISHINABEK NATION GOVERNANCE AGREEMENT OVERVIEW For more than 25 years, the Anishinabek Nation and the Government of Canada have been negotiating the proposed Anishinabek Nation Governance Agreement that will recognize, not create, the Anishinabek First Nations’ law-making powers and authority to self-govern, thus removing them from the governance provisions of the Indian Act. The First Nations that ratify the proposed Anishinabek Nation Governance Agreement (Participating First Nations) will have the power to enact laws in the following areas: leadership selection, citizenship, language and culture, and operation of government. The proposed Anishinabek Nation Governance Agreement includes the complementary Anishinabek Nation Fiscal Agreement that outlines the funding for governance-related functions. ANISHINABEK NATION GOVERNANCE AGREEMENT ROAD MAP 2007 2019 2020 The Anishinabek Nation Negotiations on the Additional Anishinabek and Canada reached a 2011 Anishinabek Nation Nation member First non-binding Agreement- Declaration of the Ngo Governance Agreement Nations to vote in May 1-30 in-Principle Dwe Waangizid conclude Anishinaabe (One Anishinaabe Family) 2009 Anishinabek Nation 2012 1995 E’Dbendaagzijig Proclamation Anishinabek Nation Naaknigewin (Citizenship of Anishinaabe 2020 2021 Chiefs-in-Assembly give Law) is approved Chi-Naaknigewin mandate to restore Anishinabek Nation Proposed jurisdiction with focus on member First Nations Effective Date: governance and education to -

Final WFN Annual Report 2016 2017

Annual Report 2016 - 2017 WASAUKSING FIRST NATION STRIVES TO PROVIDE EQUAL OPPORTUNITIES FOR ALL MEMBERS OF THE COMMUNITY TO DEVELOP, ENHANCE AND SUCCEED IN ECONOMIC GROWTH WHILE PROMOTING THE CONTINUED SOCIAL, TRADITIONAL, AND SPIRITUAL DEVELOPMENT OF ITS FIRST NATION. www.wasauksing.ca Wasauksing First Nation Annual Report 2016 - 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM CHIEF WARREN TABOBONDUNG 2 CHIEF EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR UPDATE 4 WASAUKSING FIRST NATION LEADERSHIP 5 ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT 6 WASAUKSING MARINA 7 WASAUKSING MAPLE PRODUCTS 7 FINANCE & ADMINISTRATION 8 PUBLIC WORKS 11 LANDS 13 HEALTH DEPARTMENT 16 SOCIAL SERVICES DEPARTMENT 20 EDUCATION DEPARTMENT 21 INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT 28 AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENT SUMMARY 30 Wasauksing First Nation Annual Report 2016 - 2017 MESSAGE FROM CHIEF WARREN TABOBONDUNG Ahnee, Boozho 2016/17 was a very busy year and Wasauksing has taken some very large steps in taking control of our own a airs. With community, council and administration, we will continue to develop Wasauksing’s agenda, laws and direction. As your Giima, I continue to engage with community to discuss and gather information that helps provide Council with direction on how we move forward. At this time, I would like to thank the Council of 2015/16 for the contribution in taking and leading us through these bold steps. When it came to developing the Constitution, Council had no hesitation to move forward, their vision was parallel to me as the Chief which is to protect our land, our Citizens and our future. We commend our leadership for this success and acknowledge Community and sta for following through with this great achievement. -

Minjimendaamowinon Anishinaabe

Minjimendaamowinon Anishinaabe Reading and Righting All Our Relations in Written English A thesis submitted to the College of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment for the requirements for the Degree of Doctor in Philosophy in the Department of English. University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan By Janice Acoose / Miskwonigeesikokwe Copyright Janice Acoose / Miskwonigeesikokwe January 2011 All rights reserved PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, whole or in part, may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Request for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or in part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of English University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan i ABSTRACT Following the writing practice of learned Anishinaabe Elders Alexander Wolfe (Benesih Doodaem), Dan Musqua (Mukwa Doodaem) and Edward Benton-Banai (Geghoon Doodaem), this Midewiwin-like naming Manidookewin acknowledges Anishinaabe Spiritual teachings as belonging to the body of Midewiwin knowledge. -

October 2012

Page 1 Volume 24 Issue 8 Published monthly by the Union of Ontario Indians - Anishinabek Nation Single Copy: $2.00 OCTOBER 2012 Big numbers hide huge failures: Madahbee UOI OFFICES – The Harper government is using big num- bers to impress Canadians about how much they are contributing to First Nations educational suc- cess, but the numbers are small change compared to what is over- due – and owed – say Anishina- bek Nation leaders. “The fact that it would cost $242 million just to bring current First Nations schools in Ontario up to par shows that $275 million across Canada will have mini- mal impact,” said Grand Council Chief Patrick Madahbee follow- ing the federal government an- nouncement. “The kind of dispar- ity in education funding between First Nations and schools outside of First Nations is a reflection of just how the federal government views First Nations in general. The Harper government is prov- ing that it views First Nations people as substandard so they only deserve substandard fund- ing. Education is a treaty right and that the government is break- ing yet another sacred promise.” Madahbee had just attended BILLBOARD BUDGET CUTS a summit in Gatineau, Quebec, The billboard at Saskatoon's AKA Gallery is actually an installation called "Budget Cuts, 2012, from Every Line & Every Other Line" by which concluded with Chiefs re- Cathy Busby, a Canadian artist based in Halifax. She has a PhD in Communication and MA in Media Studies from Concordia University, jecting Conservative government Montreal, was a Fulbright Scholar at New York University, and holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design plans to introduce legislation on and has been exhibiting her work internationally over the past 20 years. -

Anishinabek-PS-Annual-Report-2020

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 ANISHINABEK POLICE SERVICE Oo’deh’nah’wi…nongohm, waabung, maamawi! (Community…today, tomorrow, together!) TABLE OF CONTENTS Mission Statement 4 Organizational Charts 5 Map of APS Detachments 7 Chairperson Report 8 Chief of Police Report 9 Inspector Reports - North, Central, South 11 Major Crime - Investigative Support Unit 21 Recruitment 22 Professional Standards 23 Corporate Services 24 Financial 25 Financial Statements 26 Human Resources 29 Use of Force 31 Statistics 32 Information Technology 34 Training & Equipment 35 MISSION STATEMENT APS provides effective, efficient, proud, trustworthy and accountable service to ensure Anishinabek residents and visitors are safe and healthy while respecting traditional cultural values including the protection of inherent rights and freedoms on our traditional territory. VISION STATEMENT Safe and healthy Anishinabek communities. GOALS Foster healthy, safe and strong communities. Provide a strong, healthy, effective, efficient, proud and accountable organization. Clarify APS roles and responsibilities regarding First Nation jurisdiction for law enforcement. 4 APS ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE - BOARD STRUCTURE ANISHINABEK POLICE SERVICE POLICE COUNCIL POLICE GOVERNING AUTHORITY POLICE GOVERNING Garden River First Nation AUTHORITY COMMITEES Curve Lake First Nation Sagamok Anishnawbek First Nation Discipline Commitee Fort William First Nation Operations Commitee POLICE CHIEF Biigtigong Nishnaabeg Finance Commitee Netmizaaggaming Nishnaabeg Cultural Commitee Biinjitiwaabik Zaaging Anishinaabek -

About-The-Governance

Governance Working Group Overview Working Groups and the Anishinabek Nation Governance Initiatives The Anishinabek Nation is currently in the process of implementing two self-governance initiatives to restore inherent jurisdictional rights to Anishinabek First Nations and their people in areas of Education and Governance. The mandates for these initiatives have come from Grand Council Resolutions that are directed by the Chiefs in Assembly, as part of an overall Nation-Building strategy that includes the implementation of the Anishinabek Declaration 1980. These resolutions, which are implemented by the Leadership and technical staff of the Anishinabek Nation, have mandated initiatives such as the Restoration of Jurisdiction Project, the Constitution Development Project, the E’Dbendaagzijig Citizenship Law, the Anishinabek Child Well-Being Law, and the Education and Governance Agreement Negotiations. The Anishinabek Nation has been negotiating with Canada for the restoration of jurisdiction in Education for over 20 years, and following a successful ratification in December 2016, the Kinoomaadziwin Education Board is forging ahead with the Anishinabek Education System (AES) start-up and implementation planning, and nearing conclusion of the Master Education Agreement with the province of Ontario. Governance has been in negotiations for more than 10 years and the Agreement is nearing completion and preparing for a vote in May/June 2019. Upon completion, both self-governance agreements will enable First Nations with law-making authorities in the specific areas of Education and Governance. As part of the on-going negotiations and the development of the two agreements, First Nation Chiefs recognized the importance of having grassroots input into the negotiations, and therefore mandated the Anishinabek Nation to coordinate the development of two working groups. -

Waubetek News 2019

Waubetek Business Development Corporation “A Community Futures Development Corporation” WAUBETEK NEWS 2019 Featured Businesses this Issue INSIDE THIS ISSUE ➢ Northern Integrated Commercial Fisheries Initiative ..............pg.2 ➢Burke Stonework and Excavation - Bringing Your Landscape Dreams to Life……………………………………………….pg 3 ➢ M’Chigeeng Freshmart Store…………………………….....pg 4 ➢ Twiggs Coffee Roasters – More than just Coffee………........pg 5 ➢“Picking up Where Mother Nature Leafs Off.”…………………………….…………………….…......pg 6 ➢ WAUBETEK NEWS BRIEFS….. …………………..………pg 7 ➢ Outreach Services Spring 2019………………………....……pg 8 ➢ Touched By The Entrepreneurial Spirit....................................pg 9 ➢ Touched by the Entrepreneurial Spirit Map Guide………....pg 10 ➢ Waubetek Student Bursary Recipients………………..….....pg 11 ➢ Investing in the Aboriginal Business Spirit……………….. .pg 12 ➢ 30 years of Investing and more …………………………….pg 13 Freshly Roasted. Fair Trade. Organic. Waubetek News – Spring 2019 www.waubetek.com 2 New Program - Northern Integrated Commercial Fisheries Initiative In April, 2019, the Northern Integrated Commercial Fisheries working capital and scientific studies is not available through Initiative (NICFI) will formally launch as Canada’s newest NICFI, however. commercial fishing and aquaculture-related program. The Interest in the program was quite intense in late 2018 but aspect of this initiative dealing with commercial fisheries will Waubetek was able to gather funds for a program “soft launch” be delivered by Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the in order to support nine projects. These ranged from Waubetek Business Development Corporation will be assistance with equipment and infrastructure, expansion of supporting aquaculture developments. NICFI was created to existing operations, feasibility studies, detailed designs, assist Indigenous groups develop commercial fishing and community engagements, business plans, partnership aquaculture operations that will: be economically self- development, and travel for facility visits. -

ANISHINABEK EDUCATION SYSTEM (AES) in Partnership

ANISHINABEK EDUCATION SYSTEM (AES) in Partnership BACKGROUND STATISTICS The Anishinabek Nation Education Agreement (ANEA) is a sectoral self-government agreement under which the fed- • In total, 92% of students eral government recognizes participating Anishinabek First Nations’ jurisdiction over elementary and secondary edu- in the Anishinabek Edu- cation. cation System attend The federal Anishinabek Nation Education Act, 2017: provincially-funded • Restores legislative authority to the 23 Anishinabek First Nations over their education system (K-12), which schools. means they are no longer subject to the education provisions of the Indian Act; • Establishes and recognizes the Anishinabek Education System and its structures; AND • About 24,000 • Sets standards and other requirements for the provision of education programs. students attend school off-reserve from JK to Grade 12. WHAT IS THE KEB? • First Nations participating in the Anishinabek Education System work together • About 2,000 students through a central administrative structure called the Kinoomaadziwin Education attend school on-reserve Body (KEB). from JK to Grade 12. • The KEB supports First Nations in the delivery of education programs and ser- vices, and liaises with the Province of Ontario on education matters. WORKING RELATIONSHIPS • In August 2017, the KEB and the 23 Participating First Nations signed a formal agreement with the Province of Ontario (Ministry of Education) known as the Master Education Agreement (MEA). • Commitments outlined in the MEA are operationalized through a Multi-Year Action Plan (MYAP), currently in its second year of implementation. • Flowing from the MYAP, district school boards and First Nation communities are working in part- nership in support of programs that address Anishinabek student success and well-being. -

Chief and Council Announcements +

Magnetawan First Nation MONTHLY NEWSLETTER | APRIL 2015 10 Hwy 529, Britt, Ontario P0G 1A0 Phone: 705-383-2477 | Fax: 705-383-2566 Web Site: www.magnetawanfirstnation.com IN THIS ISSUE New Band Manager Chief and Council are pleased to announce that... Henvey Inlet First Nation On March 19th, 2015 our General Election for Band Council was held for the upcoming two year term... Species at Risk Ryan Morin "The Species at Risk boys Terry Jones and Ryan Morin are going to be hosting a workshop on Monday Spotted Along Hwy 529 April 13th 2015... COMMUNITY NOTICE Spring Runoff – Ditches and Road Please remind all children that the ditches are running real fast right now, and as a safety precaution that the children should stay away from them. Heavy equipment will be in to help clear ditches of ice and grading of road will commence, to assist the spring runoff and melt. Thank You Public Work Lloyd Myke NOTICE Please sort your Plastic, Metal, Paper, Styrofoam, and regular household garbage into individual bags before putting it out for pick up. Any unsorted bags will be left behind. Thanks! April 8, 2015 Attention: Community members/Band Members/Students As of April 7, 2015, I am working from 8:00 am to 4:30 pm as Education Counselor at the Band Office! I am looking forward to putting 100% of my time into my responsibilities to Post Secondary, Secondary and Elementary students! As a reminder, all Post Secondary students must have their funding applications in by May 31, 2015. In addition, in order for Living Allowances to be deposited into students bank accounts in September 2015, the Acceptance Letters from their respective institutions must be mailed, emailed or scanned to the Education Department.