Making Meaning out of Social Harm in Videogames

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xbox Cheats Guide Ght´ Page 1 10/05/2004 007 Agent Under Fire

Xbox Cheats Guide 007 Agent Under Fire Golden CH-6: Beat level 2 with 50,000 or more points Infinite missiles while in the car: Beat level 3 with 70,000 or more points Get Mp model - poseidon guard: Get 130000 points and all 007 medallions for level 11 Get regenerative armor: Get 130000 points for level 11 Get golden bullets: Get 120000 points for level 10 Get golden armor: Get 110000 points for level 9 Get MP weapon - calypso: Get 100000 points and all 007 medallions for level 8 Get rapid fire: Get 100000 points for level 8 Get MP model - carrier guard: Get 130000 points and all 007 medallions for level 12 Get unlimited ammo for golden gun: Get 130000 points on level 12 Get Mp weapon - Viper: Get 90000 points and all 007 medallions for level 6 Get Mp model - Guard: Get 90000 points and all 007 medallions for level 5 Mp modifier - full arsenal: Get 110000 points and all 007 medallions in level 9 Get golden clip: Get 90000 points for level 5 Get MP power up - Gravity boots: Get 70000 points and all 007 medallions for level 4 Get golden accuracy: Get 70000 points for level 4 Get mp model - Alpine Guard: Get 100000 points and all gold medallions for level 7 ghðtï Page 1 10/05/2004 Xbox Cheats Guide Get ( SWEET ) car Lotus Espirit: Get 100000 points for level 7 Get golden grenades: Get 90000 points for level 6 Get Mp model Stealth Bond: Get 70000 points and all gold medallions for level 3 Get Golden Gun mode for (MP): Get 50000 points and all 007 medallions for level 2 Get rocket manor ( MP ): Get 50000 points and all gold 007 medalions on first level Hidden Room: On the level Bad Diplomacy get to the second floor and go right when you get off the lift. -

An Exploration of Trends in Loot Boxes, Pay to Win, and Cosmetic

The changing face of desktop video game monetisation: An exploration of trends in loot boxes, pay to win, and cosmetic microtransactions in the most- played Steam games of 2010- 2019 David Zendle*, Rachel Meyer, Nick Ballou Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract It is now common practice for video game companies to not just sell copies of games themselves, but to also sell in-game bonuses or items for a small real-world fee. These purchases may be purely aesthetic (cosmetic microtransactions); confer in-game advantages (pay to win microtransactions), or contain randomised contents of uncertain value (loot boxes). The growth of microtransactions has attracted substantial interest from both gamers, academics, and policymakers. However, it is not clear either how prevalent these features are in desktop games, or when any growth in prevalence occurred. In order to address this, we analysed the play history of the 463 most-played Steam desktop games from 2010 to 2019. Results of exploratory joinpoint analyses suggested that cosmetic microtransactions and loot boxes experienced rapid growth during 2012-2014, leading to high levels of prevalence by April 2019: 71.28% of the sample played games with loot boxes at this point, and 85.89% played games with cosmetic microtransactions. By contrast, pay to win microtransactions did not appear to experience similar growth in desktop games during the period, rising gradually to a prevalence of 17.38% by November 2015, at which point growth decelerated significantly (p<0.001) to the point where it was not significantly different from zero (p=0.32). Introduction The way that the video game industry makes money has undergone important changes in recent decades. -

Jrpgs in Germany and Japan

Exploring Cultural Differences in Game Reception: JRPGs in Germany and Japan Stefan Brückner1, Yukiko Sato1, Shuichi Kurabayashi2 and Ikumi Waragai1 Graduate School of Media and Governance, Keio University1 5322 Endo, Fujisawa, Kanagawa 252-0882 Japan +81-466-49-3404 [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Cygames Research2 16-17 Nanpeidai, Shibuya, Tokyo 150-0036 Japan +81-3-6758-0562 [email protected] ABSTRACT In this paper we present the first results of an ongoing research project, focused on examining the European reception of Japanese video games, and comparing it with the reception in Japan. We hope to contribute towards a better understanding of how players’ perception and evaluation of a game are influenced by their cultural background. Applying a grounded theory approach, we conducted a qualitative content analysis of articles from German video game websites, user comments, written in response to these articles, as well as Japanese and German user reviews from the respective Amazon online stores and Steam. Focusing on the reception of three Japanese RPGs, our findings show that considerable differences exist in how various elements of the games are perceived. We also briefly discuss certain lexical differences in the way players write about games, indicating fundamental differences in how Japanese and German players talk (and think) about games. Keywords Japanese games, reception, Germany, user reviews, QDA, grounded theory INTRODUCTION In recent years, there has been a rise in attempts to utilize the vast amounts of text on digital games available online, by using natural language processing (NLP) methods. -

7. Exploring Cultural Differences in Game Reception

7. Exploring Cultural Differences in Game Reception JRPGs in Germany and Japan Stefan Brückner, Yukiko Sato, Shuichi Kurabayashi, & Ikumi Waragai Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association June 2019, Vol 4 No 3, pp 209-243 ISSN 2328-9422 © The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution — NonCommercial –NonDerivative 4.0 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/ 2.5/). IMAGES: All images appearing in this work are property of the respective copyright owners, and are not released into the Creative Commons. The respective owners reserve all rights. ABSTRACT In this paper we present the first results of an ongoing research project focused on examining the European reception of Japanese video games, and we compare it with the reception in Japan. We hope to contribute towards a better understanding of how player perception and evaluation of a game is influenced by cultural 209 210 Exploring Cultural Differences in Game Reception background. Applying a grounded theory approach, we conducted a qualitative content analysis of articles from German video game websites, user comments responding to articles, as well as Japanese and German user reviews from the respective Amazon online stores and Steam. Focusing on the reception of three Japanese RPGs, our findings show that considerable differences exist in how various elements of the games are perceived between cultures. We also briefly discuss certain lexical differences in the way players write about games, indicating fundamental differences in how Japanese and German players talk (and think) about games. Keywords Japanese games, reception, Germany, user reviews, QDA, grounded theory INTRODUCTION In recent years, there has been a rise in attempts to utilize the vast amounts of text on digital games available online, by using natural language processing (NLP) methods. -

Self-Portraits in Passing from Twenty-Two Countries

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 359 138 SO 023 189 AUTHOR Bjerstedt, Ake, Ed. TITLE Fifty Peace Educators: Self-Portraits in Passing from Twenty-Two Countries. Peace Education Reports No. 7. INSTITUTION Lund Univ. (Sweden). Malmo School of Education. REPORT NO ISSN-1101-6426 PUB DATE Apr 93 NOTE 82p. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Educational Research; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Global Approach; Higher Education; *International Education; Interviews; *Peace; *Personal Narratives; Teaching Experience IDENTIFIERS *Peace Education ABSTRACT The project group "Preparedness for Peace" of the Department of Education and Psychological Research, Malmo School of Education. Sweden, explores ways of helping children andyoung people deal constructively with questions of peace andwar. As part of its work, the project group collects viewpointson the role of schools in pursuit of "peace preparedness." In this regard, experts withspecial interests and competencies in areas related topeace education have been interviewed by the project. This document presents excerpts from interviews with 50 peace educators representing 22 different countries. Answers given by interviewees to the question "Asan introduction, could you say a few words about yourself andyour interest in the field of peace education?"are the focus of the report. (DB) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best thatcan be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** -

Video Games As Free Speech

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2014 Video Games as Free Speech Benjamin Cirrinone University of Maine - Main Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Political Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cirrinone, Benjamin, "Video Games as Free Speech" (2014). Honors College. 162. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/162 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VIDEO GAMES AS FREE SPEECH by Benjamin S. Cirrinone A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Political Science) The Honors College University of Maine May 2014 Advisory Committee: James E.Gallagher, Associate Professor of Sociology Emeritus & Honors Faculty Mark D. Brewer, Associate Professor of Political Science Richard J. Powell, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science/Leadership Studies Sol Goldman, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Political Science Mark Haggerty, Rezendes Professor for Civic Engagement, Honors College Copyright © 2014 Benjamin Cirrinone All rights reserved. This work shall not be reproduced in any form, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in review, without permission in written form from the author. Abstract The prevalence of video game violence remains a concern for members of the mass media as well as political actors, especially in light of recent shootings. However, many individuals who criticize the industry for influencing real-world violence have not played games extensively nor are they aware of the gaming community as a whole. -

Pay to Play: Video Game Monetization Patents and the Doctrine of Moral Utility

GEORGETOWN LAW TECHNOLOGY REVIEW PAY TO PLAY: VIDEO GAME MONETIZATION PATENTS AND THE DOCTRINE OF MORAL UTILITY Kirk A. Sigmon* CITE AS: 5 GEO. L. TECH. REV. 72 (2021) TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 72 II. THE GROWING COST OF VIDEO GAMES ................................................. 74 III. CONTROVERSIAL VIDEO GAME PATENTS ON DLC AND MICROTRANSACTIONS ................................................................................... 81 IV. THE CONTROVERSY BEHIND THE PSYCHOLOGY OF DLC AND MICROTRANSACTIONS ................................................................................... 86 V. A BRIEF HISTORY OF PATENTS AND “MORAL UTILITY” ........................ 89 VI. WHY MORAL UTILITY SHOULD NOT BE REVIVED FOR VIDEO GAMES .. 94 VII. CONCLUSION .......................................................................................... 98 I. INTRODUCTION Video games are now more complex and realistic than they ever have been—but making those games is not cheap. Video game development and marketing costs are sky high.1 To help recoup these costs, game developers and publishers have begun inventing increasingly clever ways to encourage users to spend more money on video games—and they are pursuing patents for those inventions. One recently granted patent seeks to drive in-game purchases by making multiplayer matches difficult for a player, encouraging that player to buy an item and, once that item is purchased and used, subtly rewarding the spending by making multiplayer matches easier.2 Another recently granted patent targets players more likely to spend money in-game by presenting them with exclusive spending opportunities, maximizing value * Shareholder, Banner Witcoff. Thanks to Ross A. Dannenberg, Scott M. Kelly, and Carlos Goldie for their invaluable input and assistance with this Article. 1 See infra Part II. 2 See U.S. Patent No. 9,789,406 (filed Oct. 17, 2017) [hereinafter Marr]. -

For Composers, Musicians, Sound Designers, and Game Developers

THE COMPLETE GUIDE TO GAME AUDIO For Composers, Musicians, Sound Designers, and Game Developers Aaron Marks CMP BOOKS Lawrence, Kansas 66046 CMP Books CMP Media LLC 1601 West 23rd Street, Suite 200 Lawrence, Kansas 66046 USA Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. In all instances where CMP is aware of a trademark claim, the product name appears in initial capital let- ters, in all capital letters, or in accordance with the vendor’s capitalization preference. Readers should contact the appropriate companies for more complete information on trademarks and trade- mark registrations. All trademarks and registered trademarks in this book are the property of their respective holders. Copyright © 2001 by CMP Media LLC, except where noted otherwise. Published by CMP Books, CMP Media LLC. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publi- cation may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher; with the exception that the program listings may be entered, stored, and executed in a computer system, but they may not be reproduced for publication. The programs in this book are presented for instructional value. The programs have been carefully tested, but are not guaranteed for any particular purpose. The publisher does not offer any warran- ties and does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information herein and is not responsible for any errors or omissions. The publisher assumes no liability for damages result- ing from the use of the information in this book or for any infringement of the intellectual property rights of third parties that would result from the use of this information. -

Download Muse Full Album Rar Download Muse Full Album Rar

download muse full album rar Download muse full album rar. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67dbce8b3f554a8b • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Muse – Discography (1999 – 2015) Muse – Discography (1999 – 2015) EAC Rip | 12xCD + 5xDVD + Blu-ray | FLAC Image + Cue + Log | Full Scans Included Total Size: 57.7 GB | 3% RAR Recovery STUDIO ALBUMS | LIVE ALBUMS | COMPILATION Label: Various | Genre: Alternative Rock. Muse’s fusion of progressive rock, electronica, and Radiohead-influenced experimentation have helped them sell millions of records and top charts worldwide. It’s all crafted by guitarist/vocalist Matthew Bellamy, bassist Chris Wolstenholme, and drummer Dominic Howard, a trio of friends who began playing music together in their hometown of Teignmouth, Devon; they started the first incarnation of the band at the age of 13, changing the name of the group from Gothic Plague to Fixed Penalty to Rocket Baby Dolls as time passed. -

Exergames and the “Ideal Woman”

Make Room for Video Games: Exergames and the “Ideal Woman” by Julia Golden Raz A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Christian Sandvig, Chair Professor Susan Douglas Associate Professor Sheila C. Murphy Professor Lisa Nakamura © Julia Golden Raz 2015 For my mother ii Acknowledgements Words cannot fully articulate the gratitude I have for everyone who has believed in me throughout my graduate school journey. Special thanks to my advisor and dissertation chair, Dr. Christian Sandvig: for taking me on as an advisee, for invaluable feedback and mentoring, and for introducing me to the lab’s holiday white elephant exchange. To Dr. Sheila Murphy: you have believed in me from day one, and that means the world to me. You are an excellent mentor and friend, and I am truly grateful for everything you have done for me over the years. To Dr. Susan Douglas: it was such a pleasure teaching for you in COMM 101. You have taught me so much about scholarship and teaching. To Dr. Lisa Nakamura: thank you for your candid feedback and for pushing me as a game studies scholar. To Amy Eaton: for all of your assistance and guidance over the years. To Robin Means Coleman: for believing in me. To Dave Carter and Val Waldren at the Computer and Video Game Archive: thank you for supporting my research over the years. I feel so fortunate to have attended a school that has such an amazing video game archive. -

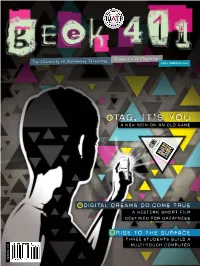

TAG, It's You! a NEW SPIN on an OLD GAME

Student Life Magazine The University of Advancing Technology Issue 5 SUMMER/FALL 2009 03 TAG, IT’S YOU A New Spin on an Old Game S N A P I T 50 D IGITAL DREAMS DO COME TRUE a Western Short FILM Destined for Greatness 24 Rise to The Surface Three Students Build a Multi-Touch Computer $6.95 SUMMER/FALL T.O.C. • • • LOOK FOR THESE MICROSOFT TAGS 04 TAG, IT'S YOU! A NEW SPIN ON AN OLD GAME TA B L E O F CON T E N T S GEEK 411 ISSUE 5 SUMMER/FALL 2009 ABOUT UAT 10 WE’RE TAKING OVER THE WORLD. JOIN US. 32 GET GEEKALICIOUS: T-SHIRT SALE 41 THE BRICKS (OUR AWESOME FACULTY) 49 THE MORTAR (OUR AWESOME STAFF) INSIDE THE TECH WORLD FEATURE 6 BIG BRAIN EVENTS STORIES 26 DEADLY TALENTED ALUMNI 35 WHAT'S YOUR GEEK IQ? 36 GO PLAY WITH YOUR DOTS 24 RISE TO THE SURFACE 38 WHAT’S HOT, WHAT’S NOT ThE RE STUDENTS BUILD A MULTI-TOUCH COMPUTER 42 DAYS OF FUTURE PAST 45 GADGETS & GIZMOS GEEK ESSENTIALS 12 GEEKS ON TOUR 18 DAY IN THE LIFE OF A DORM GEEK 30 LET THE TECH GAMES BEGIN 40 YOU KNOW YOU WANT THIS 46 HOW WE GOT SO AWESOME 47 WE GOT WHAT YOU NEED 22 GEEKILY EVER AFTER 54 GEEKS UNITE – CLUBS AND GROUPS HWTOO W UAT STUDENTS FELL IN LOVE AT FIRST SHOT STORIES ABOUT REALLY SMART PEOPLE 8 INVASION OF THE STAY PUFT BUNNY 29 RAY KURZWEIL 34 GEEK BLOGS 50 COWBOY DREAMS 20 DAVID WESSMAN IS THE MAN UAP T ROFESSOR DIRECTS FILM 16 LIVING THE GEEK DREAM 33 INTRODUCING… NEW GEEKS 14 WE DO STUFF THAT MATTERS 2 | GEEK 411 | UAT STUDENT LIFE MAGAZINE 09UT A 151 © CONTENTS COPYRIGHT BY FABCOM 20092008 LOOK FOR THESE MICROSOFT TAGS THROUGHOUT THIS S ISSUE OF GEEK 411 N AND TAG THEM A P TO GET MORE OF I THE STORY OR T BONUS CONTENT. -

Analysis of Gender and Queer Representation in Outlast II Margret

Outlasting the Binary: Analysis of Gender and Queer Representation in Outlast II Margret M. Murphy Department of Sociology SOC 401: Research Dr. Oluwakemi “Kemi” Balogun March 20, 2020 OUTLASTING THE BINARY 2 Abstract The components within Horror Media has been a topic of study for decades. A major gap in the scholarship is how representations within horror media impacts marginalized communities negatively. Using the first-person survival horror game Outlast II, I ask how these tropes accentuate the archetypes of hegemonic masculinity and emphasized femininity as well as how they conventionalize individuals that challenge the gender binary. The cutscenes, dialogue, documents, and recordings collected will be analyzed, providing evidence for the forthcoming discussions about the representation of gender and queer communities within this game. Results show that the game emphasizes similar themes commonly found in horror media. These include: the “male protector” and “damsel in distress” archetypes, the violent mistreatment of women, framing sexually transmitted diseases (STD’s) as grotesque, exclusion of primary female characters, stereotyping queer characters, and emphasis on hegemonic masculinity, a term coined by Connell (1987). This case study will provide further evidence for ongoing research on horror media and its use of the gender binary, stereotypical male/female roles, and exclusion of non- stereotypical gender non-conforming or queer characters. Keywords: videogames, horror, gender binary, hegemonic masculinity, emphasized femininity, queer representation OUTLASTING THE BINARY 3 Dedications and Acknowledgements A huge thank you to my advisor, Professor Oluwakemi “Kemi” Balogun! Thank you for giving me criticisms, advice, and ideas that were nothing but helpful in making this the best it can possibly be.