Ben Sira's Teaching on Friendship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Theognide Megarensi. Nietzsche on Theognis of Megara. a Bilingual Edition

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE De Theognide Megarensi Nietzsche on Theognis of Megara – A Bilingual Edition – Translated by R. M. Kerr THE NIETZSCHE CHANNEL Friedrich Nietzsche De Theognide Megarensi Nietzsche on Theognis of Megara A bilingual edition Translated by R. M. Kerr ☙ editio electronica ❧ _________________________________________ THE N E T ! " # H E # H A N N E $ % MM&' Copyright © Proprietas interpretatoris Roberti Martini Kerrii anno 2015 Omnia proprietatis iura reservantur et vindicantur. Imitatio prohibita sine auctoris permissione. Non licet pecuniam expetere pro aliquo, quod partem horum verborum continet; liber pro omnibus semper gratuitus erat et manet. Sic rerum summa novatur semper, et inter se mortales mutua vivunt. augescunt aliae gentes, aliae invuntur, inque brevi spatio mutantur saecla animantum et quasi cursores vitai lampada tradiunt. - Lucretius - - de Rerum Natura, II 5-! - PR"#$CE %e &or' presente( here is a trans)ation o* #rie(rich Nietzsche-s aledi!tionsarbeit ./schoo) e0it-thesis12 *or the "andesschule #$orta in 3chu)p*orta .3axony-$nhalt) presente( on 3epte4ber th 15678 It has hitherto )arge)y gone unnotice(, especial)y in anglophone Nietzsche stu(- ies8 $t the ti4e though, the &or' he)pe( to estab)ish the reputation o* the then twenty year o)( Nietzsche and consi(erab)y *aci)itate( his )ater acade4ic career8 9y a)) accounts, it &as a consi(erab)e achie:e4ent, especial)y consi(ering &hen it &as &ri;en: it entai)e( an e0pert 'no&)e(ge, not =ust o* c)assical-phi)o)ogical )iterature, but also o* co(ico)ogy8 %e recent =u(ge4ent by >"+3"+ .2017<!!2< “It is a piece that, ha( Nietzsche ne:er &ri;en another &or(, &ou)( ha:e assure( his p)ace, albeit @uite a s4a)) one, in the history o* Ger4an phi)o)ogyB su4s the 4atter up quite e)o@uently8 +ietzsche )ater continue( his %eognis stu(ies, the sub=ect o* his Crst scho)ar)y artic)e, as a stu(ent at Leip,ig, in 156 D to so4e e0tent a su44ary o* the present &or' D a critical re:ie& in 156!, as &e)) as @uotes in se:eral )e;ers *ro4 1567 on. -

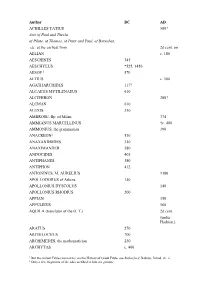

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, Etc

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, etc. at the earliest from 2d cent. on AELIAN c. 180 AESCHINES 345 AESCHYLUS *525, †456 AESOP 1 570 AETIUS c. 500 AGATHARCHIDES 117? ALCAEUS MYTILENAEUS 610 ALCIPHRON 200? ALCMAN 610 ALEXIS 350 AMBROSE, Bp. of Milan 374 AMMIANUS MARCELLINUS †c. 400 AMMONIUS, the grammarian 390 ANACREON2 530 ANAXANDRIDES 350 ANAXIMANDER 580 ANDOCIDES 405 ANTIPHANES 380 ANTIPHON 412 ANTONINUS, M. AURELIUS †180 APOLLODORUS of Athens 140 APOLLONIUS DYSCOLUS 140 APOLLONIUS RHODIUS 200 APPIAN 150 APPULEIUS 160 AQUILA (translator of the O. T.) 2d cent. (under Hadrian.) ARATUS 270 ARCHILOCHUS 700 ARCHIMEDES, the mathematician 250 ARCHYTAS c. 400 1 But the current Fables are not his; on the History of Greek Fable, see Rutherford, Babrius, Introd. ch. ii. 2 Only a few fragments of the odes ascribed to him are genuine. ARETAEUS 80? ARISTAENETUS 450? ARISTEAS3 270 ARISTIDES, P. AELIUS 160 ARISTOPHANES *444, †380 ARISTOPHANES, the grammarian 200 ARISTOTLE *384, †322 ARRIAN (pupil and friend of Epictetus) *c. 100 ARTEMIDORUS DALDIANUS (oneirocritica) 160 ATHANASIUS †373 ATHENAEUS, the grammarian 228 ATHENAGORUS of Athens 177? AUGUSTINE, Bp. of Hippo †430 AUSONIUS, DECIMUS MAGNUS †c. 390 BABRIUS (see Rutherford, Babrius, Intr. ch. i.) (some say 50?) c. 225 BARNABAS, Epistle written c. 100? Baruch, Apocryphal Book of c. 75? Basilica, the4 c. 900 BASIL THE GREAT, Bp. of Caesarea †379 BASIL of Seleucia 450 Bel and the Dragon 2nd cent.? BION 200 CAESAR, GAIUS JULIUS †March 15, 44 CALLIMACHUS 260 Canons and Constitutions, Apostolic 3rd and 4th cent. -

23. Jewish Literature and the Second Sophistic

23. JewishLiteratureand the Second Sophistic The Jews sawthemselvesasapeople apart.The Bible affirmed it,and the na- tion’sexperience seemed to confirm it.AsGod proclaimed in the Book of Levi- ticus, “Youshall be holytome, for Ithe Lordamholy, and Ihaveset youapart from otherpeoples to be mine”.¹ The idea is echoed in Numbers: “There is apeo- ple that dwells apart,not reckoned among the nations.”² Other biblical passages reinforce the sense of achosen people, selectedbythe Lord(for both favorand punishment) and placed in acategory unto themselves.³ This notion of Jewish exceptionalism recurs with frequency in the Bible, most pointedlyperhaps in the construct of the return from the Babylonian Exile when the maintenance of endogamyloomed as paramount to assert the identity of the nation.⁴ The imagewas more than amatter of self-perception. Greeks and Romans also characterized Jews as holding themselvesaloof from other societies and keepingtotheirown kind.The earliest Greek writer who discussed Jews at anylength, Hecataeus of Abdera, described them (in an otherwise favorable ac- count) as somewhat xenophobic and misanthropic.⁵ That form of labelingper- sisted through the Hellenistic period and well into the eraofthe RomanEmpire. One need onlycite Tacitus and Juvenal for piercingcomments on the subject: Jews are fiercelyhostile to gentiles and spurn the companyofthe uncircumcised.⁶ Whatever the perceptions or the constructs, however,they did not match conditions on the ground. Jews dwelled in cities and nations all over the eastern Mediterranean, spilling over also to the west,particularlyinItaly and North Af- rica. The diasporapopulation far outnumbered the Palestinian, and the large majority of the dispersed grew up in lands of Greek languageand culture— and Roman political dominance.⁷ Isolation was not an option. -

Elemental Psychology and the Date of Semonides of Amorgos Author(S): Thomas K. Hubbard Source: the American Journal of Philology, Vol

Elemental Psychology and the Date of Semonides of Amorgos Author(s): Thomas K. Hubbard Source: The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 115, No. 2 (Summer, 1994), pp. 175-197 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/295298 Accessed: 28-05-2015 20:42 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Journal of Philology. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.83.205.78 on Thu, 28 May 2015 20:42:45 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ELEMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY AND THE DATE OF SEMONIDES OF AMORGOS The date ascribed to the iambic poet Semonides of Amorgos has long been a matter of scholarly uncertainty.' Ancient chronographic sources present us with a welter of confused and contradictory state- ments; for the most part, they associate him closely with Archilochus as a poet of the early seventh century, although one ambiguous testi- monium may suggest a late sixth-century date. Modern literary histo- rians seem to favor a date in the second half of the seventh century, although with no real evidence.2 After reexamining the chronographic sources, I wish to call attention to a passage in Semonides' poetry whose bearing on this question has hitherto been neglected. -

Passionless Sex in 1 Thessalonians 4:4-5 DAVID FREDRICKSON

Word & World Volume 23, Number 1 Winter 2003 Passionless Sex in 1 Thessalonians 4:4-5 DAVID FREDRICKSON That every one of you should know how to possess his vessel in sanctification and honour; Not in the lust of concupiscence, even as the Gentiles which know not God.... (1 Thess 4:4-5 KJV) nterpreters of Paul have overburdened his statements about marriage with ideals foreign to his own purpose. Protestants are partly to blame. Dale Martin is cor- rect when he writes, “Since the inception of Protestantism, there has been a broad, concerted attempt to package Paul as a promoter of sex and marriage, in spite of (and in reaction to) most of Christian history, which has taken Paul to be an advo- cate of sexual asceticism, allowing marriage only for those too weak for celibacy.”1 Yet, if Protestants want Paul to be the chief advocate of heterosexual marriage, Or- thodox, Roman Catholic, and even some contemporary Lutheran theologians warm to the “Pauline” view of marriage, particularly the one falsely attributed to him in Eph 5. They do this because of the hierarchical ecclesiology derived from the “wife as an extension of the husband’s body” ideology found there. In short, Pauline statements about marriage have been made to bear the Protestant weight of “healthy sexuality” or the load placed on them by apologists of hierarchical ec- clesiology, but the intelligibility of his arguments breaks down under this weight of 1Dale Martin, The Corinthian Body (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995) 209. Paul’s argument in 1 Thess 4:4-5 accepts the philosophical notions of Paul’s day that sex in marriage should be without passion. -

Lyric Wisdom: Alcaeus and the Tradition of Paraenetic Poetry By

Lyric Wisdom: Alcaeus and the Tradition of Paraenetic Poetry By William Tortorelli B.A., University of Florida, 1996 Dissertation Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics at Brown University PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2011 This dissertation by William Tortorelli is accepted in its present form by the Department of Classics as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date________________ ______________________________________ Deborah Boedeker, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date________________ ______________________________________ Michael C.J. Putnam, Reader Date________________ ______________________________________ Pura Nieto Hernández, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date________________ ______________________________________ Peter M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School ii CURRICULUM VITAE William Tortorelli was born in 1973 in Bad Kreuznach, Germany. He studied Biochemistry and Classics at the University of Florida, where he was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa and graduated cum laude in 1996. He attained an M.A. in Classics from the same institution before pursuing further graduate study at Brown University in 1998. He has taught as a visiting instructor at Brigham Young University, Northwestern University, and Temple University. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to thank my advisor, Deborah Boedeker, for nurturing me intellectually throughout my exploration of archaic Greek poetry. I wish to thank Michael Putnam for his guidance as well as for being a model scholar and a model human being. I must thank Pura Nieto Hernández for being kind enough to step in toward the end of the project and guide me toward a steadier footing. All three members of my committee showed incredible patience and helped me to believe in a project I had lost all taste for. -

Philology. Linguistics P

P PHILOLOGY. LINGUISTICS P Philology. Linguistics Periodicals. Serials Cf. P215+ Phonology and phonetics Cf. P501+ Indo-European philology 1.A1 International or polyglot 1.A3-Z American and English 2 French 3 German 7 Scandinavian 9 Other (10) Yearbooks see P1+ Societies Cf. P215+ Phonology and phonetics Cf. P503 Indo-European philology 11 American and English 12 French 13 German 15 Italian 17 Scandinavian 18 Spanish and Portuguese 19 Other Congresses Cf. P505 Indo-European philology 21 Permanent. By name 23 Other Museums. Exhibitions 24 General works 24.2.A-Z Individual. By place, A-Z Collected works (nonserial) Cf. P511+ Indo-European philology 25 Monographic series. Sets of monographic works 26.A-Z Studies in honor of a particular person or institution. Festschriften. By honoree, A-Z 27 Collected works, papers, etc., of individual authors 29 Encyclopedias. Dictionaries 29.5 Terminology. Notation Cf. P152 Grammatical nomenclature Theory. Method General works see P121+ 33 General special Relation to anthropology, ethnology and culture Including Sapir-Whorf hypothesis Cf. GN1+ Anthropology 35 General works 35.5.A-Z By region or country, A-Z Relation to psychology. Psycholinguistics Cf. BF455+ Psycholinguistics (Psychology) 37 General works Study and teaching. Research 37.3 General works 37.4.A-Z By region or country, A-Z 37.45.A-Z By region or country, A-Z 37.5.A-Z Special aspects, A-Z 37.5.C37 Cartesian linguistics 37.5.C39 Categorization Cf. P128.C37 Categorization (Linguistic analysis) 1 P PHILOLOGY. LINGUISTICS P Theory. Method Relation to psychology. Psycholinguistics Special aspects, A-Z -- Continued 37.5.C64 Communicative competence Cf. -

1 Theognis Revisited

Theognis Revisited: A Historic, Thematic and Literary Reading of the Theognidean Corpus Odiseas Espanol Androutsopoulos Department of History and Classical Studies McGill Univeristy, Montreal December 2016 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in Classics (Thesis Option) © Odiseas Espanol Androutsopoulos, 2016 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 Abstract 5 Acknowledgements 6 Introduction 7 Part I: The Muddled History of Theognis 9 1. Our sources on Theognis 9 1.1.Classical and post-Classical antiquity 9 Sources from Classical antiquity 9 Sources from post-Classical antiquity 10 Information in the ancient sources 11 1.2.The Middle Ages 11 Theognis’ fame in the Middle Ages 11 Information in the Suda and the chronicles 12 2. The manuscript tradition 13 3. The historical issues surrounding the Theognidean corpus 14 3.1.Theognis as a compilation 14 Theognidean analysts and unitarians 14 The content and structure of the Theognidean corpus 15 Further indicators of a compilation 17 3.2.The dating of the Theognidean corpus 19 Views on and problems with dating Theognis 19 Indicators of an early date 20 The problem of the “Persian War” verses 22 3.3.Theognis’ Megara 23 The ancient debate on Theognis’ origins: which Megara? 23 Specific references to mainland Megara in the corpus 24 History of Nisaean Megara 25 Theognidean biographies: mapping Theognis onto Megarian history 26 Solving the debate and making sense of the Sicilian evidence: Figueira’s Pan-Megarian Theognis 27 Using the Pan-Megarian Theognis to help solve the dating problem 29 3.4.The compilation and inception of Theognis: a corpus of oral poetry 30 A series of compilations: the “analyst” view 30 A unified Theognis 31 A unified Theognis as a tradition of oral poetry 33 4. -

Itinerant Sages: the Evidence of Sirach in Its Ancient Mediterranean Context*

Itinerant Sages: The Evidence of Sirach in its Ancient Mediterranean Context* Elisa Uusimäki Abstract: This article examines passages in Sirach which posit that travel fosters understanding (Sir. 34:9–13) and that the sage knows how to travel in foreign lands (Sir. 39:4). The references are discussed in the context of two ancient Mediterranean corpora, i.e., biblical and Greek literature. Although the evidence in Sirach is insufficient for demonstrating the existence of a specific social practice, the text at least attests to an attitude of mental openness, imagining travel as a professional enterprise with positive outcomes. This article argues that the closest parallels to Sir. 34:9–13 and Sir. 39:4 are not to be found in the Hebrew Bible or Hellenistic Jewish literature but in (non-Jewish) Greek writings which refer to travels undertaken by the sages who roam around for the sake of learning. The shared travel motif helps to demonstrate that Sirach belongs to a wider Hellenistic Mediterranean context than just that of biblical literature. Keywords: Sirach, sages, education, travel, mobility, Mediterranean antiquity, Second Temple Judaism, ancient Greek writings 1. Introduction Travel or transport describe a person’s movement from one location to another, typically with a specified goal, while wandering or wayfaring may not involve a particular destination.1 Both provide the subject with liminal spaces and embodied experiences, with several possible outcomes: movement may offer a means to access new (im)material resources, enable interaction between individuals and/or shape a person through (un)expected forces, thus leading to personal development and * I am indebted to the dedicated reviewer of JSOT whose feedback helped me to improve this article considerably. -

The Mysteries of Righteousness

Texte und Studien zum Antiken Judentum herausgegeben von Martin Hengel und Peter Schäfer 40 The Mysteries of Righteousness The Literary Composition and Genre of the Sentences of Pseudo-Phocylides by Walter T.Wilson J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck) Tübingen Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Wilson, Walter T.: The mysteries of righteousness: the literary composition and genre of the sentence of Pseudo-Phocylides / bei Walter T. Wilson. - Tübingen: Mohr, 1994 (Texte und Studien zum antiken Judentum; 40) ISBN 3-16-146211-4 NE: GT © 1994 J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck) Tübingen. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (Beyond that permitted by copyricht law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by M. Fischer in Tübingen using Times typeface, printed by Guide- Druck in Tübingen on acid-free paper from Papierfabrik Buhl in Ettlingen and bound by Heinr. Koch in Tübingen. ISSN 0721-8753 For Beth oi) [i£V yaq xoii ye XQEIOOOV xai aQeiov, r] 60' ofioqppoveovxe vormaaiv olxov exr)xov avfiQ r|5e yuvt|- jtoXk' aXysa Suafieveeaai, XaQnata 6' eujievexriai, [id>aaxa 5e t' EX?OJOV arixoi. For there is nothing greater or more splendid than when man and wife dwell in their home with one heart and mind, a grief to their foes and a joy to their friends; but they themselves know it best. Homer, Odyssey VI. 182-185 Acknowledgments It is a pleasure to acknowledge here those friends and colleagues who have generously assisted with the preparation and publication of this investigation of the literary composition and genre of Pseudo-Phocylides' Sentences.