British Residents in Russia During the Crimean War Simon Dixon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

«Hermitage» - First E-Navigation Testbed in Russia

«Hermitage» - first e-Navigation testbed in Russia Andrey Rodionov CEO of “Kronstadt Technologies” (JSC) "Kronstadt Group“ (St. Petersburg, Russia) About «Kronstadt Technologies» (JSC) 2 . «Kronstadt Technologies» (Included in the Kronstadt Group) is a national leader in the field of digital technologies for marine and river transport. Kronstadt Group (until 2015 - part of Transas Group) has been operating in this market for more than 25 years. Now we are part of the largest Russian financial corporation – «SISTEMA» (SYSTEM) . We are the only Russian technology company to become a member in IALA association, which is operation agency for IMO in terms of development and implementation of e-Navigation. «Kronstadt Technologies» is a contractor for developing business road map MARINET by the order of National Technology Initiative of Russia. The company takes part in developing of business road map for improvement of regulation of Russian Federation in terms of e-Navigation and USV. The second stage of development Testbed “Hermitage” 3 . In 2016 we started creating the first testbed e-Navigation in Russia. Now the second stage of the testbed's development is taking place. This work is performed by the Kronstadt Group in cooperation with our partners. Customers - Ministry of Transport of Russia and MariNet (from National Technological Initiative). Research and development (R&D) names: “e-Sea” and “e-NAV”. Implementation period – 2016-2021. The name of testbed - "Hermitage" (in honor of the famous museum in St. Petersburg). The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia . Testbed includes the sea and the river segments. Borders of Testbed “Hermitage” in Russia 4 Implementing e-Navigation in Russia 5 The ways of implementing e-Navigation in Russia Federal target program "GLONASS" State program "National Technology Initiative" Ministry of Transport Program "MariNet" 2016 R&D "e-Sea" R&D "e-NAV" 2018 Previous experience of Kronstadt Group in the technology e-Navigation : • R&D "Approach-T“ in 2009, • R&D "Approach-Nav-T“ in 2012. -

Narratives of Social Change in Rural Buryatia, Russia

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Anthropology Theses Department of Anthropology 4-20-2010 Narratives of Social Change in Rural Buryatia, Russia Luis Ortiz-Echevarria Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/anthro_theses Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Ortiz-Echevarria, Luis, "Narratives of Social Change in Rural Buryatia, Russia." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2010. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/anthro_theses/36 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Anthropology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NARRATIVES OF SOCIAL CHANGE IN RURAL BURYATIA, RUSSIA by LUIS RAIMUNDO JESÚS ORTIZ ECHEVARRÍA Under the Direction of Jennifer Patico ABSTRACT This study explores postsocialist representations of modernity and identity through narratives of social change collected from individuals in rural communities of Buryatia, Russia. I begin with an examination of local conceptualizations of the past, present, and future and how they are imagined in places and spaces. Drawing on 65 days of fieldwork, in-depth interviews, informal discussion, and participant-observation, I elaborate on what I am calling a confrontation with physical triggers of self in connection to place, including imaginations of the countryside and -

Izhorians: a Disappearing Ethnic Group Indigenous to the Leningrad Region

Acta Baltico-Slavica, 43 Warszawa 2019 DOI: 10.11649/abs.2019.010 Elena Fell Tomsk Polytechnic University Tomsk [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7606-7696 Izhorians: A disappearing ethnic group indigenous to the Leningrad region This review article presents a concise overview of selected research findings rela- ted to various issues concerning the study of Izhorians, including works by A. I. Kir′ianen, A. V. Labudin and A. A. Samodurov (Кирьянен et al., 2017); A. I. Kir′ianen, (Кирьянен, 2016); N. Kuznetsova, E. Markus and M. Muslimov (Kuznetsova, Markus, & Muslimov, 2015); M. Muslimov (Муслимов, 2005); A. P. Chush′′ialova (Чушъялова, 2010); F. I. Rozhanskiĭ and E. B. Markus (Рожанский & Маркус, 2013); and V. I. Mirenkov (Миренков, 2000). The evolution of the term Izhorians The earliest confirmed record of Izhorians (also known as Ingrians), a Finno-Ugrian ethnic group native to the Leningrad region,1 appears in thirteenth-century Russian 1 Whilst the city of Leningrad became the city of Saint Petersburg in 1991, reverting to its pre-So- viet name, the Leningrad region (also known as the Leningrad oblast) retained its Soviet name after the collapse of the USSR. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 PL License (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/pl/), which permits redistribution, commercial and non- -commercial, provided that the article is properly cited. © The Author(s) 2019. Publisher: Institute of Slavic Studies, Polish Academy of Sciences [Wydawca: Instytut Slawistyki Polskiej Akademii Nauk] Elena Fell Izhorians: A disappearing ethnic group indigenous to the Leningrad region chronicles, where, according to Chistiakov (Чистяков, 2006), “Izhora” people were mentioned as early as 1228. -

OOB of the Russian Fleet (Kommersant, 2008)

The Entire Russian Fleet - Kommersant Moscow 21/03/08 09:18 $1 = 23.6781 RUR Moscow 28º F / -2º C €1 = 36.8739 RUR St.Petersburg 25º F / -4º C Search the Archives: >> Today is Mar. 21, 2008 11:14 AM (GMT +0300) Moscow Forum | Archive | Photo | Advertising | Subscribe | Search | PDA | RUS Politics Mar. 20, 2008 E-mail | Home The Entire Russian Fleet February 23rd is traditionally celebrated as the Soviet Army Day (now called the Homeland Defender’s Day), and few people remember that it is also the Day of Russia’s Navy. To compensate for this apparent injustice, Kommersant Vlast analytical weekly has compiled The Entire Russian Fleet directory. It is especially topical since even Russia’s Commander-in-Chief compared himself to a slave on the galleys a week ago. The directory lists all 238 battle ships and submarines of Russia’s Naval Fleet, with their board numbers, year of entering service, name and rank of their commanders. It also contains the data telling to which unit a ship or a submarine belongs. For first-class ships, there are schemes and tactic-technical characteristics. So detailed data on all Russian Navy vessels, from missile cruisers to base type trawlers, is for the first time compiled in one directory, making it unique in the range and amount of information it covers. The Entire Russian Fleet carries on the series of publications devoted to Russia’s armed forces. Vlast has already published similar directories about the Russian Army (#17-18 in 2002, #18 in 2003, and #7 in 2005) and Russia’s military bases (#19 in 2007). -

Survey of London © English Heritage 2012 1 DRAFT

DRAFT INTRODUCTION Shortly before his death in 1965 Herbert Morrison, former leader of the London County Council and Cabinet minister, looked back across a distinguished London life to the place where he had launched his career: ‘Woolwich has got a character of its own’ he reflected. ‘It doesn’t quite feel that it’s part of London. It feels it’s a town, almost a provincial town.’1 Woolwich was then at a cusp. Ahead lay devastating losses, of municipal identity when the Metropolitan Borough of Woolwich became a part of the London Borough of Greenwich, and of great manufacturing industries, so causing employment and prosperity to tumble. Fortunately for Morrison, he did not witness the fall. His Woolwich was a place that through more than four centuries had proudly anchored the nation’s navy and military and acquired a centrifugal dynamic of its own. All the while it was also a satellite of London. When metropolitan boundaries were defined in 1888 they were contorted to embrace an unmistakably urban Woolwich. Woolwich attracted early settlement and river crossings because the physical geography of the Thames basin made the locality unusually accessible. Henry VIII’s decision in 1512 to make great warships here cast the dice for the special nature of subsequent development. By the 1720s Woolwich had long been, as Daniel Defoe put it, ‘wholly taken up by, and in a manner raised from, the yards, and public works, erected there for the public service’.2 Dockyard, ordnance and artillery was the local lexicon. Arsenal was added to that in 1805. -

Saint-Petersburg, Russia

Saint-Petersburg, Russia INGKA Centres Reaching out 13 MLN to millions VISITORS ANNUALLY Perfectly located to serve the rapidly developing districts direction. Moreover, next three years primary catchment area will of the Leningradsky region and Saint-Petersburg. Thanks significantly increase because of massive residential construction to the easy transport links and 98% brand awareness, MEGA in Murino, Parnas and Sertolovo. Already the go to destination Vyborg Parnas reaches out far beyond its immediate catchment area. in Saint-Petersburg and beyond, MEGA Parnas is currently It benefits from the new Western High-Speed Diameter enjoying a major redevelopment. And with an exciting new (WHSD) a unique high-speed urban highway being created design, improved atmosphere, services and customer care, in St. Petersburg, becoming a major transportation hub. the future looks even better. MEGA Parnas meets lots of guests in spring and summer period due to its location on the popular touristic and county house Sertolovo Sestroretsk Kronshtadt Vsevolozhsk Western High-Speed Diameter Saint-Petersburg city centre Catchment Areas People Distance Peterhof ● Primary 976,652 16 km Kirovsk ● Secondary 656,242 16–40 km 56% 3 МЕТRО 29% ● Tertiary 1,701,153 > 40–140 km CUSTOMERS COME STATIONS NEAR BY YOUNG Otradnoe BY CAR FAMILIES Total area: 3,334,047 Kolpino Lomonosov Sosnovyy Bor Krasnoe Selo A region with Loyal customers MEGA Parnas is located in the very dynamic city of St. Petersburg and attracts shoppers from all over St. Petersburg and the strong potential Leningrad region. MEGA is loved by families, lifestyle and experienced guests alike. St. Petersburg and the Leningrad region MEGA Parnas is situated in the north-east of St. -

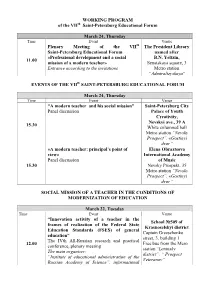

WORKING PROGRAM of the VII Saint-Petersburg Educational

WORKING PROGRAM of the VIIth Saint-Petersburg Educational Forum March 24, Thursday Time Event Venue Plenary Meeting of the VIIth The President Library Saint-Petersburg Educational Forum named after «Professional development and a social B.N. Yeltzin, 11.00 mission of a modern teacher» Senatskaya square, 3 Entrance according to the invitations Metro station “Admiralteyskaya” EVENTS OF THE VIIth SAINT-PETERSBURG EDUCATIONAL FORUM March 24, Thursday Time Event Venue “A modern teacher and his social mission” Saint-Petersburg City Panel discussion Palace of Youth Creativity, Nevskyi ave., 39 A 15.30 White columned hall Metro station “Nevsky Prospect”, «Gostinyi dvor” «A modern teacher: principal’s point of Elena Obraztsova view» International Academy Panel discussion of Music 15.30 Nevsky Prospekt, 35 Metro station “Nevsky Prospect”, «Gostinyi dvor” SOCIAL MISSION OF A TEACHER IN THE CONDITIONS OF MODERNIZATION OF EDUCATION March 22, Tuesday Time Event Venue “Innovation activity of a teacher in the School №509 of frames of realization of the Federal State Krasnoselskyi district Education Standards (FSES) of general Captain Greeschenko education” street, 3, building 1 The IVth All-Russian research and practical 12.00 Free bus from the Mero conference, plenary meeting station “Leninsky The main organizer: district”, “ Prospect “Institute of educational administration of the Veteranov” Russian Academy of Science”, informational and methodological center of Krasnoselskyi district of Saint-Petersburg, School №509 of Krasnoselskyi district March -

Lost for Words Maria Mikulcova

Lost for Words Effects of Soviet Language Policies on the Self-Identification of Buryats in Post-Soviet Buryatia Maria Mikulcova A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of MA Russian and Eurasian Studies Leiden University June 2017 Supervisor: Dr. E.L. Stapert i Abstract Throughout the Soviet rule Buryats have been subjected to interventionist legislation that affected not only their daily lives but also the internal cohesion of the Buryat group as a collective itself. As a result of these measures many Buryats today claim that they feel a certain degree of disconnection with their own ethnic self-perception. This ethnic estrangement appears to be partially caused by many people’s inability to speak and understand the Buryat language, thus obstructing their connection to ancient traditions, knowledge and history. This work will investigate the extent to which Soviet linguistic policies have contributed to the disconnection of Buryats with their own language and offer possible effects of ethnic language loss on the self-perception of modern day Buryats. ii iii Declaration I, Maria Mikulcova, declare that this MA thesis titled, ‘Lost for Words - Effects of Soviet Language Policies on the Self-Identification of Buryats in Post-Soviet Buryatia’ and the work presented in it are entirely my own. I confirm that: . This work was done wholly while in candidature for a degree at this University. Where I have consulted the published work of others, this is always clearly attributed. Where I have quoted from the work of others, the source is always given. With the exception of such quotations, this thesis is entirely my own work. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

The City's Memory: Texts of Preservation and Loss in Imperial St. Petersburg Julie Buckler, Harvard University Petersburg's Im

The City’s Memory: Texts of Preservation and Loss in Imperial St. Petersburg Julie Buckler, Harvard University Petersburg's imperial-era chroniclers have displayed a persistent, paradoxical obsession with this very young city's history and memory. Count Francesco Algarotti was among the first to exhibit this curious conflation of old and new, although he seems to have been influenced by sentiments generally in the air during the early eighteenth century. Algarotti attributed the dilapidated state of the grand palaces along the banks of the Neva to the haste with which these residences had been constructed by members of the court whom Peter the Great had obliged to move from Moscow to the new capital: [I]t is easy to see that [the palaces] were built out of obedience rather than choice. Their walls are all cracked, quite out of perpendicular, and ready to fall. It has been wittily enough said, that ruins make themselves in other places, but that they were built at Petersburg. Accordingly, it is necessary every moment, in this new capital, to repair the foundations of the buildings, and its inhabitants built incessantly; as well for this reason, as on account of the instability of the ground and of the bad quality of the materials.1 In a similar vein, William Kinglake, who visited Petersburg in the mid-1840s, scornfully advised travelers to admire the city by moonlight, so as to avoid seeing, “with too critical an eye, plaster scaling from the white-washed walls, and frost-cracks rending the painted 1Francesco Algarotti, “Letters from Count Algarotti to Lord Hervey and the Marquis Scipio Maffei,” Letter IV, June 30, 1739. -

Small State Autonomy in Hierarchical Regimes. the Case of Bulgaria in the German and Soviet Spheres of Influence 1933 – 1956

Small State Autonomy in Hierarchical Regimes. The Case of Bulgaria in the German and Soviet Spheres of Influence 1933 – 1956 By Vera Asenova Submitted to Central European University Doctoral School of Political Science, Public Policy and International Relations In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Prof. Julius Horváth Budapest, Hungary November 2013 Statement I hereby state that the thesis contains no materials accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions. The thesis contains no materials previously written and/or published by another person, except where appropriate acknowledgement is made in the form of bibliographical reference. Vera Asenova ………………... ii Abstract This thesis studies international cooperation between a small and a big state in the framework of administered international trade regimes. It discusses the short-term economic goals and long-term institutional effects of international rules on domestic politics of small states. A central concept is the concept of authority in hierarchical relations as defined by Lake, 2009. Authority is granted by the small state in the course of interaction with the hegemonic state, but authority is also utilized by the latter in order to attract small partners and to create positive expectations from cooperation. The main research question is how do small states trade their own authority for economic gains in relations with foreign governments and with local actors. This question is about the relationship between international and domestic hierarchies and the structural continuities that result from international cooperation. The contested relationship between foreign authority and domestic institutions is examined through the experience of Bulgaria under two different international trade regimes – the German economic sphere in the 1930’s and the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA) in the early 1950’s. -

This Excerpt from the First Part of the Last Journey of William Huskisson Describes the Build-Up to the Official Opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

Downloaded from simongarfield.com © Simon Garfield 2005 This excerpt from the first part of The Last Journey of William Huskisson describes the build-up to the official opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Huskisson’s fatal accident was about two hours away. The sky was brightening. For John Moss and the other directors assembled at the company offices in Crown Street it was already a day of triumph, whatever the ensuing hours might bring. They had received word that the Duke of Wellington, the Prime Minister, had arrived in Liverpool safely, and was on his way, though there appeared to be some delay. As they waited, they were encouraged by the huge crowds and the morning’s papers. Liverpool enjoyed a prosperous newspaper trade, and in one week a resident might decide between the Courier, the Mercury, the Journal, the Albion and the Liverpool Times, and while there was little to divide them on subject matter, they each twisted a Whiggish or Tory knife. Advertisements and paid announcements anchored the front pages. Mr Gray, of the Royal College of Surgeons, announced his annual trip from London to Liverpool to fit clients with false teeth, which were fixed “by capillary attraction and the pressure of the atmosphere, thereby avoiding pinning to stumps, tieing, twisting wires...” Courses improving handwriting were popular, as were new treatments for bile, nervous debility and slow fevers. The Siamese twins at the King’s Arms Hotel were proving such a draw that they were remaining in Liverpool until Saturday 25th, when, according to their promoter Captain Coffin, “they must positively leave”.