Clarifying and Settling Access to Clearing and Settlement in the Eu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft.Projectnotice to Street Nov 25 2019.V2

DR Market Announcement December 29, 2020 JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. 500 Stanton Christiana Rd. Newark, DE 19713-2107 To: FINRA Security Name: KONAMI HOLDINGS CORPORATION – Termination of Deposit Agreement JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., as depositary under the Amended and Restated Deposit Agreement dated as of April 16, 2015 (the "Deposit Agreement") among KONAMI HOLDINGS CORPORATION (the "Company"), JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., as depositary thereunder (the "Depositary"), and all Holders (defined therein) and Beneficial Owners (defined therein) from time to time of American Depositary Receipts issued thereunder evidencing American depositary shares ("ADSs") hereby notifies registered holders of ADRs ("Holders") that the termination provisions of the Deposit Agreement have been amended and the Company has instructed the Depositary to terminate the Deposit Agreement (as amended) effective January 29, 2021. ADR Termination Date: January 29, 2021 Ratio: 1 ADS: 1 Share of Common Stock CUSIP: 50046R101 ADR ISIN: US50046R1014 Underlying ISIN: JP3300200007 Country of Incorporation: Japan Custodian: Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation Please be advised the ADR issuance books for the Company are closed with immediate effect. The ADS cancellation books will remain open until the earlier of (a) February 26, 2021, if prior to March 01, 2021 the Depositary establishes an unsponsored American depositary receipt program in respect of the Company’s shares; (b) March 30, 2021, if prior to March 01, 2021, the Depositary does not establish an unsponsored American -

Shareholder Identification and Registration

Shareholder Identification and Registration Report by a Working Group mandated by the European Post Trade Group December 2015 1 1. Introduction 1.1 European Post Trade Group / EPTG Tasks and Composition The European Post Trade Group (EPTG) has been set up in 2012 on the recommendation of the European Group on Market Infrastructure. It is a joint initiative between the European Commission, the ECB, ESMA and the industry. Its members are representatives of the key players involved in post trade issues which participate in the group’s work as experts. The initiators intended to drive the dismantling of barriers to cross border safety and efficiency including identifying new issues that have developed since the second Giovannini report in 2003. The mandate also comprises encouragement to propose to compliment the legal framework in those areas as well as the work of the ECB on its Target Securities project. 1 The EPTG has set up an action list and several initiatives have been commenced. 2 1.2 EPTG Working Group Shareholder Identification and Registration Tasks and Composition During the discussions in meetings of the EPTG several issues have been identified to warrant further attention including shareholder identification and questions of “registration” procedures and the relation to settlement. Two sponsors have been designated and a Working Group has been set up.3 This Working Group was set the task to do a fact-finding exercise with respect to the two issues to identify the concerns and expectations of market participants to develop a pan- European model for both in order to propose procedures not to interrupt straight through processing (STP) in cross border exercising of shareholders rights and cross border settlement. -

The Cost of Restricting Corporate Takeovers

3 Werner Hermann and C. J. Santoni Werner Hermann, an economist at the Swiss National Bank, was a visiting scholar at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. G. J. Santoni is a protessor of economics at Ball State University Santoni’s research was supported by the George A. and Frances Ball Foundation. Scott Leitz provided research assistance. The Cost 01 Restricting Cor- porate Takeovers: A Lesson From Switzerland of takeovers is important to maintaining an effi- 1~’IANYPEOPLE in management, labor, 4 banking and Congress are alarmed about the re- cient corporate sector. cent increase in corporate takeovers. ‘These peo- A recent change in Swiss commercial practice ple believe that the risk of a takeover is detrimental to the efficient management of cor- provides important new evidence about the con- porations and not in the long-run interests of sequences of restricting corporate takeovers. the owners (see shaded insert on following ‘The Swiss Commercial Code in the past has page). As a result, they have advanced various allowed corporations to build effective barrier’s proposals to restrict corporate takeovers.’ against takeovers. Many Swiss firms have taken advantage of this legal provision to protect Others have a different view of takeovers, themselves against foreign raiders. On Nov- believing that restrictions of takeover activity ember 17, 1988, Nestle’ (by far the largest Swiss will be harmful to shareholders’ wealth. They corporation) announced that it would allow argue that takeover activity is a simple manifest- foreign investors to buy a type of share that ation of competition in the market for corporate only Swiss citizens could hold until then. -

Letter to Shareholders 2009 | Zurich Financial

Zurich Financial Services Group Annual Report 2009 Letter to Shareholders 2009 Zurich’s 2009 results reflect our continued ability to execute against a proven strategy rooted in operational excellence and financial discipline. Dr. Manfred Gentz Martin Senn Chairman of the Board of Directors Chief Executive Officer Letter to Shareholders Zurich Financial Services Group Annual Report 2009 We are proud to present to you a strong set of 2009 channels. In addition, the new business margin exceeded operating results. Our business operating profit 2 percent, illustrating the value of the significant improved by 8 percent to USD 5.6 billion, and our structural change we are making in our life business. net income increased by 6 percent to USD 3.2 billion. Furthermore, we ended 2009 with one of our Similarly, Farmers continued to post greater profitability strongest balance sheets ever, and a 17.2 percent and strong growth. Business operating profit improved business operating profit after tax return on equity by a solid 0 percent, reflecting not just the ongoing that exceeds our target. successful integration of 2st Century but also continued expense management as well as higher profitability from These results reflect our continued ability to execute Farmers Re following higher quota share arrangements. against a proven strategy rooted in operational excellence and financial discipline. Given that strength, and with And finally, total return on Group investments was full confidence in the sustainability of the Zurich strategy, 6.3 percent, including investment income, realized gains the Board will recommend at the Annual General Meeting and losses and impairments, as well as changes in a gross dividend of CHF 6.00 per share, which represents unrealized gains and losses reported in shareholders’ an exceptionally high payout of earnings to shareholders equity. -

Shareholder Information

Shareholder Information Executive Offices 2012 Annual Report on Form 10-K The Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. Copies of the firm’s 2012 Annual Report on 200 West Street Form 10-K as filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange New York, New York 10282 Commission can be accessed via our Web site at 1-212-902-1000 www.goldmansachs.com/shareholders/. www.goldmansachs.com Copies can also be obtained by Common Stock contacting Investor Relations via email at The common stock of The Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. is [email protected] listed on the New York Stock Exchange and trades under or by calling 1-212-902-0300. the ticker symbol “GS.” Transfer Agent and Registrar for Common Stock Shareholder Inquiries Questions from registered shareholders of The Goldman Information about the firm, including all quarterly earnings Sachs Group, Inc. regarding lost or stolen stock certificates, releases and financial filings with the U.S. Securities and dividends, changes of address and other issues related to Exchange Commission, can be accessed via our Web site registered share ownership should be addressed to: at www.goldmansachs.com. Computershare Shareholder inquiries can also be 480 Washington Boulevard directed to Investor Relations via email at Jersey City, New Jersey 07310 [email protected] U.S. and Canada: 1-800-419-2595 or by calling 1-212-902-0300. International: 1-201-680-6541 www.computershare.com Independent Registered Public Accounting Firm PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP PricewaterhouseCoopers Center 300 Madison Avenue New York, New York 10017 The papers used in the printing of this Annual Report are certified by © 2013 The Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. -

On Determination of Market Price of One Ordinary Registered Share of the Moscow Exchange (State Registration Number 1-05-8443-H Dated 16.11.2011)

2, 3-ya ulitsa Yamskogo Polya, bld. 7, office 301, Moscow, 125040 Tel.: +7 (495) 717-01-01 +7 (495) 557-07-97 www.evcons.ru REPORT No. 134/16 dated June 29, 2016 On determination of market price of one ordinary registered share of the Moscow Exchange (state registration number 1-05-8443-H dated 16.11.2011) Customer: Moscow Exchange Contractor: Everest Consulting Moscow 2016 EVEREST Consulting LLC 1 Att: Evgeny Fetisov CFO Moscow Exchange Dear Evgeny, Under Agreement No.134/16 dated 16.06.2016 executed by and between Everest Consulting Limited Liability Company (hereinafter Everest Consulting LLC, the Contractor), and Public Joint-Stock Company Moscow Exchange MICEX-RTS (hereinafter the Moscow Exchange, the Customer), the appraiser employed by the Contractor (hereinafter the Appraiser) carried out valuation of one registered ordinary share of the Moscow Exchange (hereinafter the Object of Valuation). The principle task and intended use of valuation was to measure the market price of the Object of Valuation for the purpose of share buyback from shareholders who voted against the corporate restructuring or failed to participate in voting in pursuance with clause 1 and clause 3 Article 75 of the Federal Law No.208-FZ On Joint-stock Companies dated 26 December 1995. The valuation was done in accordance with the Federal Law No.135-FZ On Valuation Activity in the Russian Federation dated 29 July 1998, Federal Evaluation Standard General Concepts of the Valuation, Approaches and Requirements to Carrying Out the Valuation (FES No.1) approved by the Order of the Ministry of Economy No. -

German Aspects of Acquisition Financing

Dr. Birgit Friedl European Counsel Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP, Munich 3 Dr. Birgit Friedl | Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP German Aspects of Acquisition Financing International financial investors are increasingly discovering the German market as a playing field for interesting investments and are achieving attractive returns on investment. After streamlining their portfolios, strategic investors have also rediscovered their interest in strengthening their core business via acquisitions. Underlying Structure In the majority of M&A transactions, a company either acquired off the shelf or newly incorporated in the form of a limited liability company (GmbH) functions as the purchaser of the target and as borrower under the acquisition financing. These acquisition vehicles are to a certain extent funded with equity by the shareholders, while the remaining purchase price of the target is financed with bank debt. The funds required for the subsequent debt service are to be generated from the cash-flow that the operational business of the target company produces. Furthermore, extensive securities are generally granted to the lenders. In the context of acquisitions by strategic investors, payment guarantees issued by the parent company, which is the ultimate economic beneficiary behind the trans- action, may be considered. Especially in the case of financial investors, the lenders also tend to concentrate on the target company and their operative subsidiaries as grantor of securities and issuer of guarantees. Simultaneously with the actual acquisition financing, the existing bank financing of the target group is often paid and refinanced and a new working capital 44 facility is granted. This generally takes place within the framework of a separate Dr. -

Statement of Cash Flows

CURRENTCURRENT DEVELOPMENTSDEVELOPMENTS ININ THETHE DIVISIONDIVISION OFOF CORPORATIONCORPORATION FINANCEFINANCE National Conference on Current SEC & PCAOB Developments December 6, 2005 DisclaimerDisclaimer TheThe SecuritiesSecurities andand ExchangeExchange Commission,Commission, asas aa mattermatter ofof policy,policy, disclaimsdisclaims responsibilityresponsibility forfor anyany privateprivate publicationpublication oror statementstatement byby anyany ofof itsits employees.employees. Therefore,Therefore, thethe viewsviews expressedexpressed todaytoday areare ourour own,own, andand dodo notnot necessarilynecessarily reflectreflect thethe viewsviews ofof thethe CommissionCommission oror thethe otherother membersmembers ofof thethe staffstaff ofof thethe Commission.Commission. 2 2 CorporationCorporation FinanceFinance OverviewOverview FinancialFinancial ReportingReporting andand DisclosureDisclosure IssuesIssues 3 3 CorporationCorporation FinanceFinance OVERVIEWOVERVIEW CraigCraig OlingerOlinger 4 4 OverviewOverview FYEFYE SeptemberSeptember 30,30, 20052005 OverOver 60006000 issuerissuer reviewsreviews (51%(51% ofof issuers)issuers) 26.126.1 daysdays averageaverage timetime forfor initialinitial commentscomments onon registrationregistration statementsstatements 5 5 OverviewOverview 6 6 OverviewOverview ADAD OfficesOffices -- 44 NewNew ACAsACAs Structured Finance, Transportation & Leisure: Lyn Shenk Financial Services Amit Pande Electronics & Machinery Kate Tillan Telecommunications Ivette Leon 7 7 OverviewOverview 1111 NewNew AccountingAccounting -

Hongkong Securities Clearing Company Limited 12/F Chinachem Exchange Square 1 Hoi Wan Street Quarry Bay, Hongkong

ACT X(l/I ~40 SEION UNITED STATES RULE l if -ÇC~'; J(/ / I SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE =MMJSSION PULIC .... ~ WASHINGTON. D.C. 20549 AVATT.ABI "71L=i ~~A : _ DIVISION OF . I t INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT July 13, 1995 Ms. Susane Chan, General Counsel Mr. Suren D. Gangai, Principal Legal Adviser Hongkong Securities Clearing Company Limited 12/F Chinachem Exchange Square 1 Hoi Wan Street Quarry Bay, Hongkong Dear Ms. Chan and Mr. Gangai: Thank you for your letter of May 10, 1995 regarding the proposed changes to the operations of Hongkong Securities Clearing Company Limited ("Hongkong Clearing"). You state that Hongkong Clearing will terminate the Depository Contract now in place with Hongkong and Shanghai Bank Corporation Limited ("Hongkong Bank") and implement its own "in-house" depository operations. Based on the information contained in your letter and the appendices, particularly your representation that Hongkong Clearing's in-house depository operations will provide the same functions and similar operational procedures as those services previously provided by Hongkong Bank, it does not appear that any amendment is necessary to our no-action response to Hongkong Clearing under Rule 17f-5(c) (2) (iii) of the Investment Company Act of 1940. 1./ If we can be of any additional assistance in this matter, please contact me at (202) 942 - 0660. Sincerely, (j tt.v- 0 ; ~~~"' JOhn V. 0' Hanlon Special Counsel 1./ Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company Limited (pub. avail. Sept. 8, 1992). "1 HONGKONG~m~Ji CLEANG e HONG KONG SECURITIES ClEARING COMPANY LIMITED W m: q::9 #.. ~ ~ ~ PJ . 10 May 1995 r- Mr Thomas Harman Chief Counsel Investment Management Division US Securities & Exchange Commission 450 Fifth Street, N. -

View Annual Report

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) ¨ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR x ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For The Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2012. OR ¨ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For The Transition Period From To OR ¨ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of event requiring this shell company report Commission file number: 001-33863 XINYUAN REAL ESTATE CO., LTD. (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) N/A (Translation of Registrant’s name into English) Cayman Islands (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) 27/F, China Central Place, Tower II 79 Jianguo Road, Chaoyang District Beijing 100025 People’s Republic of China (Address of principal executive offices) Tom Gurnee Xinyuan Real Estate Co., Ltd 27F, China Central Place, Tower II, 79 Jianguo Road, Chaoyang District Beijing 100025 People’s Republic of China Tel: (86-10) 8588-9390 Fax: (86-10) 8588-9300 (Name, Telephone, E-mail and/or Facsimile number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered American Depositary Shares, each representing two New York Stock Exchange common shares, par value US$0.0001 per share Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title of Class) Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act: None (Title of Class) Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the Issuer’s classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report 141,938,398 common shares, par value US$0.0001 per share, as of December 31, 2012. -

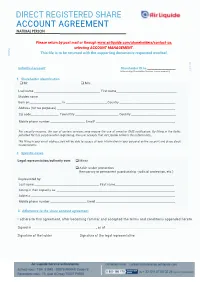

Direct Registered Share Account Agreement Natural Person

DIRECT REGISTERED SHARE ACCOUNT AGREEMENT NATURAL PERSON Please return by post mail or through www.airliquide.com/shareholders/contact-us, 05 selecting ACCOUNT MANAGEMENT. /2020 This file is to be returned with the supporting documents requested overleaf. GC - CCT Individual account Shareholder ID no. ____________________ (allocated by Shareholder Services to new accounts) 1. Shareholder identification Mr. Mrs. Last name ______________________________________________ First name__________________________________________ Maiden name________________________________________________________________________________________________ Born on ______________________ In _____________________________Country _______________________________________ Address (for tax purposes) __________________________________________________________________________________ Zip code ___________________ Town/City ______________________________ Country _______________________________ Mobile phone number ________________________ Email* _______________________________________________________ For security reasons, the use of certain services may require the use of email or SMS notification. By filling in the fields provided for this purpose when registering, the user accepts that Air Liquide collects this information. *By filling in your email address, you will be able to access all your information in your personal online account and place stock market orders. 2. Specific cases Legal representation/authority over: Minor Adult under protection (temporary or permanent -

Culture and Corporate Law Reform: a Case Study of Brazil

CULTURE AND CORPORATE LAW REFORM: A CASE STUDY OF BRAZIL ERICA GORGA* ABSTRACT The Brazilian capital markets are insufficient to provide com- panies with adequate financing. A 2001 reform in the Brazilian Corporate Law sought to strengthen Brazil's capital markets by providing stronger investor protection. Many of these latest re- forms, however, turn out to be merely palliative, because control- ling shareholders were able to capture the legislation in its crucial aspects. In this Article, I argue that public choice theory does not offer a comprehensive explanation of the legal reform outcome in the face of the particulars of the Brazilian institutional environ- ment. The objective of the research is to develop an alternative ap- proach to the public choice model by building upon Douglass North's work. In this approach, culture is incorporated into the economic model to account for divergent outcomes of similar pro- . Ph.D. in Commercial Law, University of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Professor of Law, Fundaqao Getulio Vargas Law School at Sao Paulo. Former Lecturer, Uni- versity of Texas School of Law at Austin, and Research Fellow of the Center for Law, Business and Economics, University of Texas School of Law. Former Visit- ing Scholar at Stanford Law School. I am greatly indebted to Professors Bernard Black and Rachel Sztajn for their invaluable suggestions throughout my work on this project. I am grateful to Pro- fessors Michael Klausner, A. Gledson de Carvalho, Michael Halberstam and Lee Alston for helpful comments and conversations. I am thankful to the participants of the 20th Conference of the European Association of Law and Economics, of the Stanford's John M.