Adenomyosis and Infertility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Infertility Diagnosis and Treatment

UnitedHealthcare® Oxford Clinical Policy Infertility Diagnosis and Treatment Policy Number: INFERTILITY 008.12 T2 Effective Date: July 1, 2021 Instructions for Use Table of Contents Page Related Policies Coverage Rationale ....................................................................... 1 • Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH) Gonadotropins Documentation Requirements ...................................................... 2 • Human Menopausal Gonadotropins (hMG) Definitions ...................................................................................... 3 • Preimplantation Genetic Testing Prior Authorization Requirements ................................................ 3 Applicable Codes .......................................................................... 3 Related Optum Clinical Guideline Description of Services ................................................................. 3 • Fertility Solutions Medical Necessity Clinical Benefit Considerations .................................................................. 7 Guideline: Infertility Clinical Evidence ........................................................................... 8 U.S. Food and Drug Administration ........................................... 14 References ................................................................................... 15 Policy History/Revision Information ........................................... 18 Instructions for Use ..................................................................... 18 Coverage Rationale See Benefit Considerations -

Recurrent Miscarriage

Elizabeth Taylor, MD, FRCSC, Mohammed Bedaiwy, MD, PhD, Mahmoud Iwes, MD Recurrent miscarriage Management of pregnancy loss includes investigating causes, addressing modifiable risk factors, and providing supportive care in the first trimester of pregnancy. ABSTRACT: Early miscarriages are arly miscarriage has been re Genetic causes those occurring within the first 12 ported to occur in 17% to 31% The risk of miscarriage increases completed weeks of gestation. Re- E of pregnancies,1,2 and is de with maternal age. At age 20 to 24 current miscarriage, defined as two fined as a nonviable intrauterine the risk is approximately 10%, with or more consecutive pregnancy loss- pregnancy with either an empty ges risk increasing to nearly 80% by age es, affects 3% of couples trying to tational sac or a gestational sac con 45.5 The relationship between mis conceive and can cause consider- taining an embryo or fetus without carriage risk and maternal age can be able distress. The risk of miscarriage fetal heart activity within the first explained by the increasing rate of oo increases with maternal age. Genet- 12 completed weeks of gestation.3 cyte aneuploidy that occurs as women ic abnormalities, uterine anomalies, Recurrent miscarriage occurs in 3% grow older. In one study, oocytes and endocrine dysfunction can all of couples trying to conceive. The examined during in vitro fertilization lead to miscarriage. Other causes of American Society for Reproductive (IVF) treatment had only a 10% risk miscarriage are autoimmune disor- Medicine (ASRM) defines recurrent of being aneuploid in women younger ders such as antiphospholipid syn- miscarriage as two or more failed than age 35, but by age 43 the risk of drome and chronic endometritis. -

Male Infertility and Risk of Nonmalignant Chronic Diseases: a Systematic Review of the Epidemiological Evidence

282 Male Infertility and Risk of Nonmalignant Chronic Diseases: A Systematic Review of the Epidemiological Evidence Clara Helene Glazer, MD1 Jens Peter Bonde, MD, DMSc, PhD1 Michael L. Eisenberg, MD2 Aleksander Giwercman, MD, DMSc, PhD3 Katia Keglberg Hærvig, MSc1 Susie Rimborg4 Ditte Vassard, MSc5 Anja Pinborg, MD, DMSc, PhD6 Lone Schmidt, MD, DMSc, PhD5 Elvira Vaclavik Bräuner, PhD1,7 1 Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Address for correspondence Clara Helene Glazer, MD, Department of Bispebjerg University Hospital, Copenhagen NV, Denmark Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Bispebjerg University 2 Departments of Urology and Obstetrics/Gynecology, Stanford Hospital, Copenhagen NV, Denmark University School of Medicine, Stanford, California (e-mail: [email protected]). 3 Department of Translational Medicine, Molecular Reproductive Medicine, Lund University, Lund, Sweden 4 Faculty Library of Natural and Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen K, Denmark 5 Department of Public Health, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark 6 Department of Obstetrics/Gynaecology, Copenhagen University Hospital, Hvidovre, Denmark 7 Mental Health Center Ballerup, Ballerup, Denmark Semin Reprod Med 2017;35:282–290 Abstract The association between male infertility and increased risk of certain cancers is well studied. Less is known about the long-term risk of nonmalignant diseases in men with decreased fertility. A systemic literature review was performed on the epidemiologic evidence of male infertility as a precursor for increased risk of diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and all-cause mortality. PubMed and Embase were searched from January 1, 1980, to September 1, 2016, to identify epidemiological studies reporting associations between male infertility and the outcomes of interest. Animal studies, case reports, reviews, studies not providing an accurate reference group, and studies including Downloaded by: Stanford University. -

Diagnostic Evaluation of the Infertile Female: a Committee Opinion

Diagnostic evaluation of the infertile female: a committee opinion Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Birmingham, Alabama Diagnostic evaluation for infertility in women should be conducted in a systematic, expeditious, and cost-effective manner to identify all relevant factors with initial emphasis on the least invasive methods for detection of the most common causes of infertility. The purpose of this committee opinion is to provide a critical review of the current methods and procedures for the evaluation of the infertile female, and it replaces the document of the same name, last published in 2012 (Fertil Steril 2012;98:302–7). (Fertil SterilÒ 2015;103:e44–50. Ó2015 by American Society for Reproductive Medicine.) Key Words: Infertility, oocyte, ovarian reserve, unexplained, conception Use your smartphone to scan this QR code Earn online CME credit related to this document at www.asrm.org/elearn and connect to the discussion forum for Discuss: You can discuss this article with its authors and with other ASRM members at http:// this article now.* fertstertforum.com/asrmpraccom-diagnostic-evaluation-infertile-female/ * Download a free QR code scanner by searching for “QR scanner” in your smartphone’s app store or app marketplace. diagnostic evaluation for infer- of the male partner are described in a Pregnancy history (gravidity, parity, tility is indicated for women separate document (5). Women who pregnancy outcome, and associated A who fail to achieve a successful are planning to attempt pregnancy via complications) pregnancy after 12 months or more of insemination with sperm from a known Previous methods of contraception regular unprotected intercourse (1). -

Heavy Menstrual Bleeding

25/06/2018 Definition • Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is defined as excessive menstrual blood loss which interferes with a woman's physical, social, emotional and/or material quality of life. Heavy Menstrual Bleeding (HMB): Replaced ‘menorrhagia’ Objective definition of HMB >80mL/ cycle or duration of >7 days Causes and Management • It can occur alone or in combination with other symptoms (e.g. intermenstrual bleeding, pelvic pain, pressure symptoms) Dr. William (Wee-Liak) Hoo, MD MRCOG Consultant Gynaecologist Prevalence King’s College Hospital NHS FT • The prevalence of HMB in objective studies (9 to 14%) and subjective studies 20 to 52%) in studies based on subjective assessment. • In the UK, almost 1.5 million women consult their General Practitioners UKCPA Women’s Health Group Masterclass (GPs) each year with menstrual complaints and the annual treatment cost Friday 22nd June 2018 exceeds £65 million. Causes • Uterine: Uterine fibroids (dysmenorrhoea, palpable mass, pressure symptoms) Adenomyosis (dysmenorrhoea, subfertility) Endometrial polyps (intermenstrual bleeding) Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)/ infection (vaginal discharge, pelvic pain, intermenstrual and postcoital bleeding and pyrexia) Malignancy or atypical hyperplasia (irregular/ postcoital/ intermenstrual bleeding, pelvic pain, weight loss). • Ovarian: Polycystic ovary syndrome (acne, hursuitism) • Systemic diseases: Hypothyroidism (fatigue, constipation, cold intolerance and hair and skin changes) Coagulation disorders (e.g. von Willebrand disease) Liver -

Age and Fertility: a Guide for Patients

Age and Fertility A Guide for Patients PATIENT INFORMATION SERIES Published by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine under the direction of the Patient Education Committee and the Publications Committee. No portion herein may be reproduced in any form without written permission. This booklet is in no way intended to replace, dictate or fully define evaluation and treatment by a qualified physician. It is intended solely as an aid for patients seeking general information on issues in reproductive medicine. Copyright © 2012 by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR REPRODUCTIVE MEDICINE Age and Fertility A Guide for Patients Revised 2012 A glossary of italicized words is located at the end of this booklet. INTRODUCTION Fertility changes with age. Both males and females become fertile in their teens following puberty. For girls, the beginning of their reproductive years is marked by the onset of ovulation and menstruation. It is commonly understood that after menopause women are no longer able to become pregnant. Generally, reproductive potential decreases as women get older, and fertility can be expected to end 5 to 10 years before menopause. In today’s society, age-related infertility is becoming more common because, for a variety of reasons, many women wait until their 30s to begin their families. Even though women today are healthier and taking better care of themselves than ever before, improved health in later life does not offset the natural age-related decline in fertility. It is important to understand that fertility declines as a woman ages due to the normal age- related decrease in the number of eggs that remain in her ovaries. -

World-Renowned Expert in Infertility Presents Findings to European

World-Renowned Expert in Infertility Presents Findings to European Conference After Two Recurrent Miscarriages, Patients Should be Thoroughly Evaluated for Risk Factors Dr. William Kutteh, M.D., one of the world’s leading researchers in recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL), was invited to present his latest discoveries to theEuropean Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE). Dr. Kutteh’s research on recurrent pregnancy loss calls for early intervention after the second miscarriage, a change in how physicians currently treat the condition. RPL is defined as three or more consecutive miscarriages that occur before the 20th week of pregnancy. In the general population, miscarriage occurs in 20 percent of all pregnancies, but recurrent miscarriage occurs in only 5 percent of all women seeking pregnancy. Dr. Kutteh’s study, the largest of its kind on recurrent miscarriage, scientifically proved what many physicians intrinsically knew. The 2010 study, published in Fertility and Sterility-- Diagnostic Factors Identified in 1020 Women with Two Versus Three or More Recurrent Pregnancy Losses--found that even after only two pregnancy losses, a definitive cause for RPL could be determined in two-thirds of patients in the study. Dr. Kutteh’s research showed that there was no statistical difference in women with RPL who had two pregnancy losses, and those who had three or more losses, proving that earlier intervention was appropriate. Patients with RPL are now encouraged to begin testing for known risk factors for infertility after the second miscarriage. Determining Risk Factors for Recurrent Miscarriage Recurrent miscarriage causes include anatomic, hormonal, autoimmune, infectious, genetic, or hematologic issues. Expeditiously determining the causes of miscarriage can lead to more targeted treatment, and for 67 percent of patients, a successful full-term pregnancy. -

Anovulation and PCOS

Anovulatory Infertility and PCOS ESHRE, Kiev 2010 Adam Balen MD, FRCOG Professor of Reproductive Medicine Leeds Teaching Hospitals, UK Disclosures: Medical advisor to Ferring, Organon SP Causes of Anovulatory Infertility Learning Objectives 1. To understand the causes of anovulation 2. Knowledge of the correct diagnostic tests 3. Effective assessment and diagnosis to plan appropriate ovulation induction therapy Hypothalamus GnRH Pituitary FSH LH Oestradiol, inhibins Progesterone……. LH FSH theca cells granulosa cells testosterone aromatase oestradiol oocytte Two cell – two gonadotrophin theory of oestrogen synthesis The Menstrual Cycle pmol/l 350 80 300 70 250 60 50 200 40 nmol/l 150 & 30 100 20 50 10 IU/L 0 0 0 2 4 6 8 10121416182022242628 E2 FSH LH P4 Causes of Anovulatory Infertility Group I: weight loss, systemic illness Hypothalamic/ Kallmann’s syndrome pituitary failure hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism Hyperprolactinaemia Hypopituitarism Group II: PCOS h/p dysfunction Group III: Premature ovarian failure (POF) Ovarian failure Resistant ovary syndrome (ROS) Causes of Anovulatory Infertility Group I: weight loss, systemic illness Hypothalamic/ Kallmann’s syndrome pituitary failure hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism Hyperprolactinaemia Hypopituitarism Group II: PCOS h/p dysfunction Group III: Premature ovarian failure (POF) Ovarian failure Resistant ovary syndrome (ROS) Causes of Anovulatory Infertility Group I: weight loss, systemic illness 5% Hypothalamic/ Kallmann’s syndrome pituitary failure hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism Hyperprolactinaemia Hypopituitarism Group II: PCOS 90% h/p dysfunction Group III: Premature ovarian failure (POF) 5% Ovarian failure Resistant ovary syndrome (ROS) Investigations 1. FSH, LH, oestradiol 2. Prolactin / TFTs 3. Testosterone (SHBG) 4. AMH...... 5. GTT, lipid profile 6. Ultrasound scan 7. Semen analysis 8. -

Module 3: Reproductive Tract Infections

Reproductive Tract Infections Reproductive Health Epidemiology Series Module 3 2003 Department of Health and Human Services REPRODUCTIVE TRACT INFECTIONS REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH EPIDEMIOLOGY SERIES: MODULE 3 June 2003 The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) provided funding for this project through a Participating Agency Service Agreement with CDC (936-3038.01). REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH EPIDEMIOLOGY SERIES—MODULE 3 REPRODUCTIVE TRACT INFECTIONS Divya A. Patel, MPH Nancy M. Burnett, BS Kathryn M. Curtis, PhD Technical Editors Susan Hillis, PhD Polly Marchbanks, PhD U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Division of Reproductive Health Atlanta, Georgia, U.S.A. 2003 CONTENTS Learning Objectives .........................................................................................1 Overview of Reproductive Tract Infections (RTIs) ............................................3 Prevalence of RTIs .......................................................................................3 What Are the Most Commonly Occurring RTIs in Developing Countries? ....4 Sequelae of Untreated RTIs .........................................................................4 How Are RTIs Transmitted? ........................................................................7 How Are RTIs and Their Sequelae Linked With Key Health-Related Development Programs? ...............................................8 General Model of the Epidemiology -

Recurrent Pregnancy Loss: Diagnosis and Treatment

Medical Coverage Policy Effective Date ............................................. 2/15/2021 Next Review Date ....................................... 2/15/2022 Coverage Policy Number .................................. 0284 Recurrent Pregnancy Loss: Diagnosis and Treatment Table of Contents Related Coverage Resources Overview .............................................................. 1 Comparative Genomic Hybridization Coverage Policy ................................................... 1 (CGH)/Chromosomal Microarray Analysis (CMA) General Background ............................................ 3 for Selected Hereditary Conditions Medicare Coverage Determinations .................. 11 Genetic Testing for Reproductive Carrier Screening and Coding/Billing Information .................................. 11 Prenatal Diagnosis Hydroxyprogesterone Caproate Injection References ........................................................ 14 Immune Globulin Infertility Services INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE The following Coverage Policy applies to health benefit plans administered by Cigna Companies. Certain Cigna Companies and/or lines of business only provide utilization review services to clients and do not make coverage determinations. References to standard benefit plan language and coverage determinations do not apply to those clients. Coverage Policies are intended to provide guidance in interpreting certain standard benefit plans administered by Cigna Companies. Please note, the terms of a customer’s particular benefit plan document [Group Service -

Management of Adenomyosis a Review of Characteristic Imaging Findings and Treatment Options, with an Emphasis on the Use of Uterine Artery Embolization

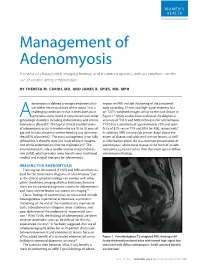

WOMEN’S HEALTH Management of Adenomyosis A review of characteristic imaging findings and treatment options, with an emphasis on the use of uterine artery embolization. BY THERESA M. CARIDI, MD, AND JAMES B. SPIES, MD, MPH denomyosis is defined as ectopic endometrial tis- myosis on MRI include thickening of the junctional sue within the musculature of the uterus.1 It is a zone exceeding 12 mm and high-signal-intensity foci challenging condition in that it often overlaps in on T2/T1-weighted images similar to the case shown in symptoms and is found in conjunction with other Figure 1.4 Many studies have evaluated the diagnostic Agynecologic disorders, including endometriosis and uterine accuracy of TVUS and MRI techniques for adenomyosis. leiomyoma (fibroids).2 The typical clinical manifestations TVUS has a sensitivity of approximately 72% and speci- of adenomyosis occur in women who are 40 to 50 years of ficity of 81% versus 77% and 89% for MRI, respectively.8 age and include abnormal uterine bleeding and dysmenor- In addition, MRI can provide greater detail about the rhea (65% of patients).1 The exact pathogenesis is not fully extent of disease and additional uterine lesions, as well defined but is thought to be the result of direct invagina- as information about the less common presentation of tion of the endometrium into the myometrium.3 The adenomyosis, where focal disease in the form of an ade- interventionalist’s role is to offer uterine artery emboliza- nomyoma is present rather than the more typical diffuse tion (UAE), which provides some benefits over traditional adenomyosis findings. -

Sonography of Adenomyosis

3105jumonline.qxp:Layout 1 4/19/12 9:48 AM Page 805 SOUND JUDGMENT SERIES Sonography of Adenomyosis Khaled Sakhel, MD, Alfred Abuhamad, MD Invited paper denomyosis was first described by Rokitansky in 1860 as “cystosarcoma adenoides uterinum” and was later defined A by Von Recklinghausen in 1896. It is a common condition that predominantly affects women in the late reproductive years. Adenomyosis has been noted to occur in about 30% of the general female population and in up to 70% of hysterectomy specimens depending on the definition of the entity.1 The diagnosis can be The Sound Judgment Series consists of made with sonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), but invited articles highlighting the clinical this article will show that sonography should be the imaging modal- value of using ultrasound first in specific ity of choice for adenomyosis. clinical diagnoses where ultrasound has Definition shown comparative or superior value. The series is meant to serve as an educational Adenomyosis is defined by the presence of ectopic endometrial tool for medical and sonography students glands and stroma within the myometrium. The presence of ectopic and clinical practitioners and may help endometrial glands and stroma induces a hypertrophic and hyper- integrate ultrasound into clinical practice. plastic reaction in the surrounding myometrial tissue. Clinical Presentation Most patients with adenomyosis are asymptomatic. Symptoms related to adenomyosis include dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, and menstrual menometrorrhagia. Adeno- myosis presents most commonly as a diffuse disease involving the entire myometrium (Figure 1). It can also present in a focal area of the uterus, known as adenomyoma (Figure 2).