Voltairine De Cleyre: More of an Anarchist Than a Feminist?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EMMA GOLDMAN, ANARCHISM, and the “AMERICAN DREAM” by Christina Samons

AN AMERICA THAT COULD BE: EMMA GOLDMAN, ANARCHISM, AND THE “AMERICAN DREAM” By Christina Samons The so-called “Gilded Age,” 1865-1901, was a period in American his tory characterized by great progress, but also of great turmoil. The evolving social, political, and economic climate challenged the way of life that had existed in pre-Civil War America as European immigration rose alongside the appearance of the United States’ first big businesses and factories.1 One figure emerges from this era in American history as a forerunner of progressive thought: Emma Goldman. Responding, in part, to the transformations that occurred during the Gilded Age, Goldman gained notoriety as an outspoken advocate of anarchism in speeches throughout the United States and through published essays and pamphlets in anarchist newspapers. Years later, she would synthe size her ideas in collections of essays such as Anarchism and Other Essays, first published in 1917. The purpose of this paper is to contextualize Emma Goldman’s anarchist theory by placing it firmly within the economic, social, and 1 Alan M. Kraut, The Huddled Masses: The Immigrant in American Society, 1880 1921 (Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, 2001), 14. 82 Christina Samons political reality of turn-of-the-twentieth-century America while dem onstrating that her theory is based in a critique of the concept of the “American Dream.” To Goldman, American society had drifted away from the ideal of the “American Dream” due to the institutionalization of exploitation within all aspects of social and political life—namely, economics, religion, and law. The first section of this paper will give a brief account of Emma Goldman’s position within American history at the turn of the twentieth century. -

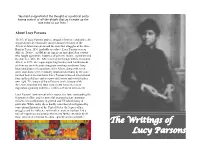

The Writings of Lucy Parsons

“My mind is appalled at the thought of a political party having control of all the details that go to make up the sum total of our lives.” About Lucy Parsons The life of Lucy Parsons and the struggles for peace and justice she engaged provide remarkable insight about the history of the American labor movement and the anarchist struggles of the time. Born in Texas, 1853, probably as a slave, Lucy Parsons was an African-, Native- and Mexican-American anarchist labor activist who fought against the injustices of poverty, racism, capitalism and the state her entire life. After moving to Chicago with her husband, Albert, in 1873, she began organizing workers and led thousands of them out on strike protesting poor working conditions, long hours and abuses of capitalism. After Albert, along with seven other anarchists, were eventually imprisoned or hung by the state for their beliefs in anarchism, Lucy Parsons achieved international fame in their defense and as a powerful orator and activist in her own right. The impact of Lucy Parsons on the history of the American anarchist and labor movements has served as an inspiration spanning now three centuries of social movements. Lucy Parsons' commitment to her causes, her fame surrounding the Haymarket affair, and her powerful orations had an enormous influence in world history in general and US labor history in particular. While today she is hardly remembered and ignored by conventional histories of the United States, the legacy of her struggles and her influence within these movements have left a trail of inspiration and passion that merits further attention by all those interested in human freedom, equality and social justice. -

Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction.....................................................................................................................2 2. The Principles of Anarchism, Lucy Parsons....................................................................3 3. Anarchism and the Black Revolution, Lorenzo Komboa’Ervin......................................10 4. Beyond Nationalism, But not Without it, Ashanti Alston...............................................72 5. Anarchy Can’t Fight Alone, Kuwasi Balagoon...............................................................76 6. Anarchism’s Future in Africa, Sam Mbah......................................................................80 7. Domingo Passos: The Brazilian Bakunin.......................................................................86 8. Where Do We Go From Here, Michael Kimble..............................................................89 9. Senzala or Quilombo: Reflections on APOC and the fate of Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio...........................................................................................................................91 10. Interview: Afro-Colombian Anarchist David López Rodríguez, Lisa Manzanilla & Bran- don King........................................................................................................................96 11. 1996: Ballot or the Bullet: The Strengths and Weaknesses of the Electoral Process in the U.S. and its relation to Black political power today, Greg Jackson......................100 12. The Incomprehensible -

Anarchism and Nineteenth-Century American Political Thought

CHAPTER 16 Anarchism and Nineteenth-Century American Political Thought Crispin Sartwell Introduction Although it is unlikely that any Americans referred to themselves as “anar- chists” before the late 1870s or early 1880s, anti-authoritarian and explicitly anti-statist thought derived from radical Protestant and democratic traditions was common among American radicals from the beginning of the nineteenth century. Many of these same radicals were critics of capitalism as it emerged, and some attempted to develop systematic or practical alternatives to it. Prior to the surge of industrialization and immigration that erupted after the Civil War—which brought with it a brand of European “collectivist” politics associ- ated with the likes of Marx and Kropotkin—the character of American radi- calism was decidedly individualistic. For this reason among others, the views of such figures as Lucretia Mott, William Lloyd Garrison, Josiah Warren, Henry David Thoreau, Lysander Spooner, and Benjamin Tucker have typically been overlooked in histories of anarchism that emphasize its European communist and collectivist strands. The same is not true, interestingly, of Peter Kropotkin, Emma Goldman, Voltairine de Cleyre and other important social anarchists of the period, all of whom recognized and even aligned themselves with the tradition of American individualist anarchism. Precursors In 1637, Anne Hutchinson claimed the right to withdraw from the Puritan the- ocracy of the Massachusetts Bay Colony on the sole authority of “the voice of [God’s] own spirit to my soul.”1 Roger Williams founded Rhode Island on similar grounds the previous year. Expanding upon and intensifying Luther’s 1 “The Trial and Interrogation of Anne Hutchinson” [1637], http://www.swarthmore.edu/ SocSci/bdorsey1/41docs/30-hut.html. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Hippolyte Havel E Os Artistas Do Revolt Hippolyte Havel and the Artists of Revolt

Hippolyte Havel e os artistas do Revolt Hippolyte Havel and the artists of Revolt Allan Antliff Professor titular de História da Arte na Universidade de Victoria (Canada). RESUMO: Este artigo consiste em um estudo de caso acerca das relações entre o anarquismo e os movimentos artísticos que romperam as convenções e as formas estéticas estabelecidas no início do século XX até a I Guerra Mundial, como o futurismo e o cubismo. Apresenta as atividades de Hippolyte Havel, anarquista tcheco, que morou em Nova Iorque, nesse período, e demonstra também o empenho deste e especialmente de seu círculo de artistas e militantes em divulgar, fortalecer e experimentar tais correntes estéticas e libertárias. Destaca dentre os periódicos que ele fundou: O Almanaque Revolucionário e o jornal A Revolta, assim como as contribuições que estes receberam de diversos artistas envolvidos com a contestação de forças conservadoras e capitalistas. Palavras-chave: anarquismo, futurismo, cubismo, inicio do século XX. ABSTRACT: This article consists of a case study about the relationship between anarchism and artistic movements that broke conventions and established aesthetic forms in the early twentieth century until World War I, as Futurism and Cubism. It presents the activities of Hippolyte Havel, Czech anarchist who lived in New York during this period, and also demonstrates the commitment of him and specially of of artists and activists around him to publicize, strengthen and experience such aesthetic and libertarian currents. It highlighted two periodicals he founded: The Revolutionary Almanac and the jornal Revolt, as well as the contributions they received from various artists involved in contesting the conservative and capitalist forces. -

Christina Hoff Sommers

A Conversation with CHRISTINA HOFF SOMMERS A resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and former philosophy professor, Christina Hoff Sommers is a thoughtful analyst and trenchant critic of radical feminism. In this conversation, Sommers and Kristol discuss how American feminism, once focused on practical questions such as equal opportunity in employment for women, instead became a radical ideology that questioned the reality of sex differences. Narrating her own experiences as a speaker on college campuses, Sommers explains how the radical feminism of today's universities stifles debate. Finally, Sommers explains a recent controversy in the video game community, which she defends from charges of sexism in a widely-publicized episode known as "GamerGate." On claims of a “rape epidemic” on campus, Sommers says: It’s the result of advocacy research. You can get very alarming findings if you’re willing to interview a non-representative sample of people and if you’re willing to include a lot of behavior most of us don’t think of as assault. If you just play with those, you can get an epidemic. Rape, like all crimes, is way down. It’s at I think a 41- year low. [Rape on campus] is not 1 in 4, or 1 in 5 women, but something like 1 in 50. Still too much. But not [an epidemic]. On the feminist denial of sex differences, Sommers says: Femininity and masculinity are real. Women tend to be more nurturing and risk-averse and have usually a richer emotional vocabulary. Men tend to be a little less explicit about their emotions. -

A Content Analysis of the Women Against Feminism Tumblr Page Lyndsey S

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Theses and Dissertations 2015 A Content Analysis of the Women Against Feminism Tumblr Page Lyndsey S . Collins Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Collins, Lyndsey S ., "A Content Analysis of the Women Against Feminism Tumblr Page" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 2559. http://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd/2559 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Content Analysis of the Women Against Feminism Tumblr by Lyndsey S. Collins A Thesis Presented to the Graduate and Research Committee of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in Sociology Lehigh University May 18, 2015 © 2015 Copyright (Lyndsey S. Collins) ii Thesis is accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Sociology. A Content Analysis of the Women Against Feminism Tumblr Page Lyndsey Collins ____________________ Date Approved Dr. Jacqueline Krasas Dr. Yuping Zhang Dr. Nicola Tannenbaum iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my thesis advisor, Dr. Jacqueline Krasas, who has provided me with invaluable insights, support, and encouragement throughout the entirety of this process. In addition, I would like to thank my committee members, Dr. Nicola Tannenbaum -

Presentations Introduction Recent Feminist De

Beyond the Generational Line: An Exploration of Feminist Online Sites and Self-(Re)presentations Yi-lin Yu National Ilan University, Taiwan Abstract This article deals with the feminist generation issue by tracing the transition from generational to non-generational thinking in recent feminist discourse on third-wave feminism. Informed by certain feminist recommendations of affording alternative paradigms in place of the oceanic wave metaphor to describe the rela- tionships between different feminists, this study offers the insights gained from an investigation with three feminist online sites, The F Word, Eminism, and Guerrilla Girls, in which these online feminists have participated in building up a third wave consciousness or a third space site through their engagement in (re)presenting their feminist selves and identities. In developing a both/and third wave con- sciousness, these online feminists have bypassed the dualistic understanding of sec- ond and third wave feminism and reached a cross-generational commonality of adhering to feminist ideology and coalition in cyberspace as a third space. Through a content analysis of their online feminist self-(re)presentations, this pa- per concludes by arguing that they have not only reformulated the concept of third wave feminism but also worked toward a new configuration of third space narratives and subjectivities that sheds light on contemporary feminist thinking about feminist genealogy and history. Key words third-wave feminism, feminist generation, feminist online sites, self-(re)presentation Introduction Recent feminist development of third-wave discourses has been bom- barded with a conundrum regarding generational debates. Although 54 ❙ Yi-lin Yu some feminist scholars are preoccupied with using familial metaphors to depict different feminist generations, others have called forth a rethink- ing of the topic in non-generational terms. -

Louise Michel

also published in the rebel lives series: Helen Keller, edited by John Davis Haydee Santamaria, edited by Betsy Maclean Albert Einstein, edited by Jim Green Sacco & Vanzetti, edited by John Davis forthcoming in the rebel lives series: Ho Chi Minh, edited by Alexandra Keeble Chris Hani, edited by Thenjiwe Mtintso rebe I lives, a fresh new series of inexpensive, accessible and provoca tive books unearthing the rebel histories of some familiar figures and introducing some lesser-known rebels rebel lives, selections of writings by and about remarkable women and men whose radicalism has been concealed or forgotten. Edited and introduced by activists and researchers around the world, the series presents stirring accounts of race, class and gender rebellion rebel lives does not seek to canonize its subjects as perfect political models, visionaries or martyrs, but to make available the ideas and stories of imperfect revolutionary human beings to a new generation of readers and aspiring rebels louise michel edited by Nic Maclellan l\1Ocean Press reb� Melbourne. New York www.oceanbooks.com.au Cover design by Sean Walsh and Meaghan Barbuto Copyright © 2004 Ocean Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN 1-876175-76-1 Library of Congress Control No: 2004100834 First Printed in 2004 Published by Ocean Press Australia: GPO Box 3279, -

Albert Parsons Last Words

Albert Parsons last words Albert Parsons last words: reprinted in Lucy Parsons, The Life of Albert R. Parsons (Chicago, 1889) 211- 212 Cook County Bastille, Cell No. 29, Chicago, August 20, 1886. My Darling Wife: Our verdict Ns morning cheers the lw" of tyrants throughout the world, and the result will be ….There was no evidence that any one of the eight doomed men knew of, or advised, or abetted the Haymarket tragedy. But what does that matter? The privileged class demands a victim,and we are offered a sacrifice to appease the hungry yells of an infuriated mob of millionaires who will be contented with nothing less than our lives. Monopoly triumphs! Labor in chains ascends the scaffold for having dared to cry out for liberty and rightl Well, my poor, dear wife, I, personally, feel sorry for you and the helpless little babes of our loins. You I bequeath to the people, a woman of the people. I have one request to make of you: Commit no rash act to yourself when I am gone, but take up the great cause of Socialism where I am compelled to lay it down. My children - well, their father had better die in the endeavor to secure their liberty and happiness than live contented in a society which condemns nine-tenths of its children to a life of wage-slavery and poverty. Bless them; I love them unspeakably, my poor helpless little ones. Ah, wife, living or dead, we are as one. For you my affection is everlasting. For the people - humanity. -

Do Atheism and Feminism Go Hand-In-Hand?: a Qualitative Investigation of Atheist Men’S Perspectives About Gender Equality

Do Atheism and Feminism Go Hand-in-Hand?: A Qualitative Investigation of Atheist Men’s Perspectives about Gender Equality Rebecca D. Stinson1 The University of Iowa Kathleen M. Goodman Miami University Charles Bermingham The University of Iowa Saba R. Ali The University of Iowa ABSTRACT: Drawing upon semi-structured interviews with 10 self-identified atheist men in the American Midwest, this qualitative study explored their perspectives regarding atheism, gender, and feminism. The data was analyzed using consensual qualitative research methodology (Hill, Thompson, & Williams, 1997). Results indicated these men had a proclivity for freethought—a commitment to questioning things and prioritizing reason over all else. They believed gender differences were primarily due to cultural and social influence in society. Gender inequality was highlighted as a problem within the U.S. and throughout the world, however this belief did not necessarily lead to being feminist-identified. There appeared to be a pathway linking their intellectual orientation, atheism, and belief in gender equality. KEYWORDS: ATHEISTS, MEN, GENDER EQUITY, FEMINISM 1 Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to: Rebecca D. Stinson, The University of Iowa, Department of Psychological and Quantitative Foundations, 361 Lindquist Center North, Iowa City, IA 52242, email: [email protected]. Secularism and Nonreligion, 2, 39-60 (2013). © Rebecca D. Stinson. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License. Published at: www.secularismandnonreligion.org. DO ATHEISM AND FEMINISM GO HAND-IN-HAND? STINSON Introduction Atheists are individuals who do not believe in a god2 or gods. It is difficult to calculate the number of atheists in the United States because of the various terms atheists use to identify themselves (e.g., humanist, skeptic, non-believer; see Zuckerman, 2009), and because atheists may hesitate to self-identify as atheists due to the negative consequences associated with the label (Arcaro, 2010).