The Climate Movement As Agent of a Societal Transformation Towards A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Solutions” Issue, Spring 2008 Change Our Sources of Electricity Arjun Makhijani Is an Engineer Who’S Been Thinking About Energy for More Than 35 Years

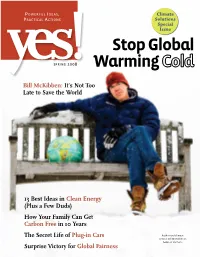

Powerful Ideas, Climate PractIcal actIons Solutions Special Issue Stop Global yes!sPrIng 2008 Warming Bill McKibben: It’s Not Too Late to Save the World 13 Best Ideas in Clean Energy (Plus a Few Duds) How Your Family Can Get Carbon Free in 10 Years The Secret Life of Plug-in Cars Author and climate activist Bill McKibben at home in Vermont Surprise Victory for Global Fairness “One way or another, the choice will be made by our generation, but it will affect life on earth for all generations to come.” Lester Brown , Earth Policy Institute Tsewang Norbu was selected by his Himalayan village to be trained at the Barefoot College of Tilonia, India, in the installation and repair of solar photovoltaic units. All solar units were brought to the village across the 18,400- foot Khardungla Pass by yak and on villagers’ backs. photo by barefoot photographers of tilonia. copyright 2008 barefoot college, tilonia, rajastan, india, barefootcollege.org yesm a g a z i! n e www.yesmagazine.org Reprinted from the “Climate Solutions” Issue, Spring 2008 Change Our Sources of Electricity Arjun Makhijani is an engineer who’s been thinking about energy for more than 35 years. When he heard a presentation ISSUE 45 claiming we needed to go fossil-carbon free by 2050, he didn’t YES! THEME GUIDE think it could be done. X years of research later, he’s changed his mind. His book, Carbon-Free and Nuclear-Free: A Roadmap for U.S. Energy Policy, tells exactly how it can be done. Here’s how Makhijani sees the energy supply changing for buildings, CLIMATE SOLUTIONStransportation and electricity. -

2019 (November 2018 – October 2019)

QUAKER EARTHCARE WITNESS ANNUAL REPORT November 2018 - October 2019 Affirming our essential unity with nature Above: Friends visit Jim and Kathy Kessler’s restored native plant habitat during the Friends General Conference Gathering in Iowa. OUR WORK THIS YEAR Quaker Earthcare Witness has grown over the last 32 years out of a deepening sense of QUAKER ACTIVISM & spiritual connection with the natural world. From this has come an urgency to work on the critical EDUCATION issues of our times, including climate and environmental justice. This year we are excited to see that more people This summer we sponsored the QEW Earthcare Center are mobilizing around the eco-crises than ever before, at the Friends General Conference annual gathering, both within and beyond the Religious Society of Friends. including scheduling and hosting presentations every afternoon, showcasing what Friends are doing regarding With your help, Quaker Earthcare Witness is Earthcare, displaying resources to share, and giving responding to the growing need for inspiration talks. We offered presentations on climate justice, and support for Friends and Meetings. indigenous concerns, eco-spirituality, activism and hope, permaculture, and children’s education. We also QEW is the largest network of Friends working on sponsored a field trip to a restored prairie (thanks to Jim Earthcare today. We work to inspire spirit-led action Kessler, QEW Steering Committee member, who planned toward ecological sustainability and environmental the trip and restored, along with his wife Kathy, this plot justice. We provide inspiration and resources to Friends of Iowa prairie). throughout North America by distributing information in our newsletter, BeFriending Creation, on our website Our General Secretary, Communications Coordinator, quakerearthcare.org and through social media. -

Duane Elgin Endorsements for Choosing Earth “Choosing Earth Is the Most Important Book of Our Time

CHOOSING EARTH Humanity’s Great Transition to a Mature Planetary Civilization Duane Elgin Endorsements for Choosing Earth “Choosing Earth is the most important book of our time. To read and dwell within it is an awakening experience that can activate both an ecological and spiritual revolution.” —Jean Houston, PhD, Chancellor of Meridian University, philosopher, author of The Possible Human, Jump Time, Life Force and many more. “A truly essential book for our time — from one of the greatest and deepest thinkers of our time. Whoever is concerned to create a better future for the human family must read this book — and take to heart the wisdom it offers.” —Ervin Laszlo is evolutionary systems philosopher, author of more than one hundred books including The Intelligence of the Cosmos and Global Shift. “This may be the perfect moment for so prophetic a voice to be heard. Sobered by the pandemic, we are recognizing both the fragility of our political arrangements and the power of our mutual belonging. As Elgin knows, we already possess the essential ingredient —our capacity to choose.” —Joanna Macy, author of Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We're in Without Going Crazy, is root teacher of the Work That Reconnects and celebrated in A Wild Love for the World: Joanna Macy and the Work of Our Time. “Duane Elgin has thought hard — and meditated long — about what it will take for humanity to evolve past our looming ecological bottleneck toward a future worth building. There is wisdom in these pages to light the way through our dark and troubled times.” —Richard Heinberg is one of the world’s foremost advocates for a shift away from reliance on fossil fuels; author of Our Renewable Future, Peak Everything, and The End of Growth. -

Arab Youth Climate Movement

+ Arab Youth Climate Movement UNEP – ROWA Regional Stakeholders Meeting + From Rio to Doha + Rio+20 + UNEP’s Role in Civil Society engagement Build on the Rio+20 outcomes para. 88h and 99 in particular, and to make sure that we see progress: The need for an international convention on procedural rights, as well as regional conventions with compliance mechanisms. The need for UNEP to show leadership when implementing its new mandate under para 88h and to promote mechanisms for a strengthening of public participation in International Environmental Governance, not only within its own processes but also across the whole IEG (as it has done in the past with its Bali Guidelines). + + Sept 2012 - Birth of the Arab Youth Climate Movement (AYCM) + + Arab Youth Climate Movement The Arab Youth Climate Movement (AYCM) is an independent body that works to create a generation-wide movement across the Middle East & North Africa to solve the climate crisis, and to assess and support the establishment of legally binding agreements to deal with climate change issue within international negotiations. The AYCM has a simple vision – we want to be able to enjoy a stable climate similar to that which our parents and grandparents enjoyed. + COP18 + Day of Action – Key Messages Climate change is a threat to all life on the planet. Unfortunately, the Arab countries have so far been the only region that is ignoring the threat of climate change. Arab leaders must fulfill their responsibilities towards future generations, by working constructively and strongly on the national and international level to achieve greenhouse gas emission reduction in the region and globally. -

C H a P T E R Iv

CHAPTER IV Moving forward: youth taking action and making a difference The combined acumen and involvement of all individuals, from regular citizens to scientific experts, will be needed as the world moves forward in implementing climate change miti- gation and adaptation measures and promot- ing sustainable development. Young people must be prepared to play a key role within this context, as they are the ones who will live to R IV experience the long-term impact of today’s crucial decisions. TE The present chapter focuses on the partici- pation of young people in addressing climate change. It begins with a review of the various mechanisms for youth involvement in environ- HAP mental advocacy within the United Nations C system. A framework comprising progressive levels of participation is then presented, and concrete examples are provided of youth in- volvement in climate change efforts around the globe at each of these levels. The role of youth organizations and obstacles to partici- pation are also examined. PROMOTING YOUTH ture. In addition to their intellectual contribution and their ability to mobilize support, they bring parTICipaTION WITHIN unique perspectives that need to be taken into account” (United Nations, 1995, para. 104). THE UNITED NATIONS The United Nations has long recognized the Box IV.1 importance of youth participation in decision- making and global policy development. Envi- The World Programme of ronmental issues have been assigned priority in Action for Youth on the recent decades, and a number of mechanisms importance of participation have been established within the system that The World Programme of Action for enables youth representatives to contribute to Youth recognizes that the active en- climate change deliberations. -

AYCC 2018 IMPACT REPORT WE’RE FIGHTING for CLIMATE JUSTICE WE’RE FIGHTING for CLIMATE JUSTICE Our Mission Young People Want to Grow up in a Kinder, Safer World

AYCC 2018 IMPACT REPORT WE’RE FIGHTING FOR CLIMATE JUSTICE WE’RE FIGHTING FOR CLIMATE JUSTICE Our Mission Young people want to grow up in a kinder, safer world. But old and dirty fossil fuels like coal and gas are polluting our air and warming our planet,and the companies profiting off this damage are manipulating our politicians. To ensure a safe climate for our generation, powered by clean renewable energy, we’ve got to build unprecedented people power, led by those with most at stake, to squash the dirty dollars of the fossil fuel lobby. WHAT IS CLIMATE JUSTICE? The climate crisis is unjust, because those that have done the least to cause the problem, feel the effects first and worst. And we think this is unfair. Working for climate justice means all people, regardless of where they’re born, their age, or the colour of their skin - everyone has access to a safe climate and healthy environment, and are empowered to create solutions to the climate crisis that work for them. The climate crisis is a moment to rethink the way this world operates, ensuring we don’t create the same problems in the future. If we embed justice and sustainability at the heart of this transition, we can create a brighter future for all. WHAT WE DO: SEED INDIGENOUS YOUTH CLIMATE NETWORK: Led by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth, Seed is a branch of the AYCC that is empowering Indigenous young people to lead climate justice campaigns and create change in their communities. CAMPAIGNS THAT WIN: We work together as a movement to make a difference through campaigns that reduce climate pollution, move Australia beyond fossil fuels and supercharge the transition to 100% renewable energy. -

Climate Futures: Youth Perspectives

Conference briefing Climate Futures: Youth Perspectives February 2021 William Finnegan #clClimateFutures cumberlandlodge.ac.uk @CumberlandLodge Foreword This briefing document has been prepared to guide and inform discussions at Climate Futures: Youth Perspectives, the virtual conference we are convening from 9 to 18 March 2021. It provides an independent review of current research and thinking, and information about action being taken to address the risks associated with our rapidly changing climate. In March, we are convening young people from schools, colleges and universities across the UK, together with policymakers, charity representatives, activists, community practitioners and academics, for a fortnight of intergenerational dialogue on some of the biggest challenges facing the planet today. We are providing a platform for young people to express their views, visions and expectations for climate futures, ahead of the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow, this November. Ideas and perspectives from the Cumberland Lodge conference will be consolidated into a summary report, to be presented to the Youth4Climate: Driving Ambition meeting (Pre-COP26) in Milan this September. We are grateful to our freelance Research Associate, Bill Finnegan, for preparing this resource for us. Bill will be taking part in our virtual conference and writing our final report. The draft report will be reviewed and refined at a smaller consultation involving conference participants and further academics and specialists in the field of climate change, before being published this summer. I hope that you find this briefing useful, both for the conference discussions and your wider work and study. I look forward to seeing you at the conference. -

Faith After the Anthropocene

Faith after the the after Anthropocene Faith • Matthew Wickman and Sherman Jacob Faith after the Anthropocene Edited by Matthew Wickman and Jacob Sherman Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Religions www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Faith after the Anthropocene Faith after the Anthropocene Editors Matthew Wickman Jacob Sherman MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade • Manchester • Tokyo • Cluj • Tianjin Editors Matthew Wickman Jacob Sherman BYU Humanities Center California Institute of Integral Studies USA USA Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Religions (ISSN 2077-1444) (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions/special issues/ Faith Anthropocene). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03943-012-3 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-03943-013-0 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Andrew Seaman. c 2020 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Editors .............................................. vii Matthew Wickman and Jacob Sherman Introduction: Faith after the Anthropocene Reprinted from: Religions 2020, 11, 378, doi:10.3390/rel11080378 .................. -

Running Head: STRATEGIES for EFFECTIVE ENGAGEMENT 1

Running head: STRATEGIES FOR EFFECTIVE ENGAGEMENT 1 Strategies for Effective Engagement A Guide for Youth Environmental Activists Sarah A. Voska University of Wisconsin- Parkside Author’s Note For Correspondence, direct emails to [email protected]. STRATEGIES FOR EFFECTIVE ENGAGEMENT 2 Abstract This guidebook will address the topic of youth engagement strategies for environmental activists. Through collaboration across regions, sectors and industries, we can accomplish more to protect our planet. This project encompasses various aspects of activism: focusing primarily on organization management and communication. The guidebook will be shared with current or aspiring activists, to provide them with a framework from which to launch strategic campaigns and best utilize limited resources through the development of smart goals and project management guidelines. This paper aspires to delineate what makes a campaign successful, and what strategies are most effective to spur engagement. It includes observational data, and research from the fields of sustainability psychology, marketing, strategic management, and education. The guide was designed to empower youth activists to promote sustainability initiatives in their communities using the tactics optimized by businesses and management professionals. Keywords: Activism, Act on Climate, Care About Climate, Climate Change, Communication, COP, Environmental Action, Environmentalist, Non-profits, Power Mapping, Strategic Planning, UNFCCC. STRATEGIES FOR EFFECTIVE ENGAGEMENT 3 Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the constant support of family, friends, colleagues and neighbors. First and foremost, my family has been incredible. Thank you to my parents for teaching me to be a critical thinker and respectful of the natural world. Thanks for giving me the tools I need and allowing me to explore and discover, and for supporting me while I’m traveling or at home. -

An Exploratory Study of Online Community Building in the Youth Climate Change Movement

Fighting for Their Future: An Exploratory Study of Online Community Building in the Youth Climate Change Movement Emily Wielk George Washington University, USA Alecea Standlee Gettysburg College, USA DOI: https://doi.org/10.18778/1733-8077.17.2.02 Keywords: Abstract: While offline iterations of the climate activism movement have spanned decades, today on- Digital Ethnography; line involvement of youth through social media platforms has transformed the landscape of this social Climate Activism; movement. Our research considers how youth climate activists utilize social media platforms to create Youth; Social Media; and direct social movement communities towards greater collective action. Our project analyzes narrative Social Movements framing and linguistic conventions to better understand how youth climate activists utilized Twitter to build community and mobilize followers around their movement. Our project identifies three emergent strategies, used by youth climate activists, that appear effective in engaging activist communities on Twit- ter. These strategies demonstrate the power of digital culture, and youth culture, in creating a collective identity within a diverse generation. This fusion of digital and physical resistance is an essential compo- nent of the youth climate activist strategy and may play a role in the future of emerging social movements. Emily Wielk is a current graduate student in the Wom- Alecea Standlee is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Get- en’s, Gender, and Sexuality Program (Public Policy track), tysburg College, in the United States. Her scholarship examines as well as a teaching assistant in the Department of Sociol- the implications of the integration and normalization of online ogy at George Washington University. -

Youth Climate Movements - Overview and Resources

Youth Climate Movements - Overview and Resources Background on Youth Strikes In the United States, youth are being organized by U.S. Climate Strikes, with the goal of March 15, 2019 being a major turning point for youth engagement across America. Protests and actions are being organized across California and the United States, for example: ● San Francisco: Youth are organizing to meet at Diane Feinstein’s office for a protest between 12-3pm on Friday March 15, 2019. ● Sacramento: Youth are organizing at the state capital for a protest between 12-2pm on Friday March 15, 2019. Students are being encouraged to organize acts of solidarity on their school campus. This movement is also being paired with the one-year anniversary (March 14th) of the #Enough movement (protesting Congress’ inaction on gun violence). In 2019, #Enough has grown into the #Enough - Youth Week of Action, to take place between March 11 - 15th, and concluding with standing in solidarity with the Youth Climate Strikes on Friday, March 15th. Overview of Youth Climate Movement There is momentum building worldwide to make 2019 a historical turning point for youth engagement on the issue of Climate Change. The release of the Special Report, “Global Warming of 1.5 Degrees Celsius,” by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in October 2018, increased momentum for youth engagement on the issue of climate change. This is largely due to dire warning that the impacts of climate change like extreme weather are already deadly and damaging, and that humans have just 12 years to limit devastating worldwide warming. -

Mexican Youth Climate Movement

Mexican Youth Climate Movement April 21st, 2021 To the esteemed Heads of State and Government at the Leaders Summit on Climate, We, as Mexico´s youth, would like to deliver a message of the utmost urgency. We are addressing you not only as political leaders, but also as the captains of our common ship — this unique, gorgeous planet Earth that is home to everything you cherish and everyone you love. The climate crisis is the biggest threat humanity has ever faced. The future of today’s youth and generations yet born depends on our capacity to transcend our divisions to think and act collectively to meet this existential challenge. As you gather for the Climate Summit, we are deeply concerned that President Lopez Obrador is actively working to take our country backwards with the adoption of reforms to our electric industry law that would increase Mexico’s annual greenhouse gas emissions in 2024 by 32% over 2020 levels according to analysis by the Mexican Climate Initiative.I The reforms erect major new barriers to clean energy deployment to ensure new markets for dirty, heavy fuel oil produced by our national oil company, PEMEX. As you know, the next generations around the world will experience much greater global temperature and climate change impacts—increased and more severe floods, cyclones, droughts, heat waves, water scarcity, etc.— than older age groups, who will not live to see the more extreme impacts of climate change materialize. On March 24th, 16 Mexican youth climate organizations and more than 200 individual young people filed a petition for protection of constitutional rights challenging these reforms to the Electricity Industry Act that would reverse the nation’s transition to clean energy.