Hispanic Economic Outlook Spring 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Minority Report 2018

theMINORITYREPORT The annual news of the AEA’s Committee on the Status of Minority Groups in the Economics Profession, the National Economic Association, and the American Society of Hispanic Economists Issue 10 | Winter 2018 HISTORICALLY BLACK COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES AND HISPANIC-SERVING INSTITUTIONS ARE A RICH SOURCE FOR THE ECONOMICS PIPELINE By Rhonda V. Sharpe, Women’s Institute for Science, Equity and Race, and Omari H. Swinton, Howard University The US Census Bureau projects that by 2060, 57 percent of the US population will identify as racially nonwhite or as ethnically Hispanic.1 As the United States becomes more racially and ethnically diverse, a diverse population of economists will be crucial to ensuring that economic analysis and policy recommendations are inclusive of the needs of all Americans. As we show below, historically black colleges and universities and Hispanic-serving institutions can be a rich pipeline for building a more inclusive economics field. WHAT DEFINES HISTORICALLY BLACK The “prior to 1964” requirement is significant because COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES AND Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made it illegal HISPANIC-SERVING INSTITUTIONS? to discriminate because of color, race, or national origin. Therefore, all institutions of higher education The Higher Education Act of 1965 (as amended) defines established after 1964 would have been open to blacks. a historically black college or university as: Unlike historically black colleges and universities or tribal Any historically black college or university that was colleges and universities, classification as an HSI is not established prior to 1964, whose principal mission based on an institution’s mission at its point of origin was, and is, the education of black Americans, but on whom it serves, which in turn is influenced by the and that is accredited by a nationally recognized demographics of its location. -

Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity

Copyright By Omar Gonzalez 2019 A History of Violence, Masculinity, and Nationalism: Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity By Omar Gonzalez, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History California State University Bakersfield In Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts in History 2019 A Historyof Violence, Masculinity, and Nationalism: Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity By Omar Gonzalez This thesishas beenacce ted on behalf of theDepartment of History by their supervisory CommitteeChair 6 Kate Mulry, PhD Cliona Murphy, PhD DEDICATION To my wife Berenice Luna Gonzalez, for her love and patience. To my family, my mother Belen and father Jose who have given me the love and support I needed during my academic career. Their efforts to raise a good man motivates me every day. To my sister Diana, who has grown to be a smart and incredible young woman. To my brother Mario, whose kindness reaches the highest peaks of the Sierra Nevada and who has been an inspiration in my life. And to my twin brother Miguel, his incredible support, his wisdom, and his kindness have not only guided my life but have inspired my journey as a historian. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis is a result of over two years of research during my time at CSU Bakersfield. First and foremost, I owe my appreciation to Dr. Stephen D. Allen, who has guided me through my challenging years as a graduate student. Since our first encounter in the fall of 2016, his knowledge of history, including Mexican boxing, has enhanced my understanding of Latin American History, especially Modern Mexico. -

Pub Type Edrs Price Descriptors

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 263 272 UD 024 548 TITLE Hispanic Heritage: References, Resources and Realities. INSTITUTION New York State Education Dept., Albany. Bureau of Bilingual Education. PUB DATE 85 NOTE 51p. AVAILABLE FROMThe University of the State of New York, State Education Department, Bureau of Bilingual Education, Albany, New York, NY 12234. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Cultural Background; *Cultural Education; Elementary Secondary Education; *Hispanic American Culture; *Hispanic Americans ABSTRACT This booklet is a resource guide for use during Hispanic Heritage week and throughout the year to encourage learning about the many contributions Hispanics have made to our country. Part I describes Hispanic countries, giving brief facts about population, languages, racial and ethnic groups, capital city, religions, government, historical notes, geography, and economy. The countries are listed alphabetically except for Spain which comes first. Part II considers Hispanics in the United States and highlights four major groups. This section includes a brief demographic overview, followed by specific discussion of Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and Dominicans, with demographic data for each group. Part III gives global contributions and achievements of Hispanics, first from an historical perspective, focusing primarily on individuals. These achievements are listed in chronological order from 1900-1984. Next are achievements in politics, including data on number of elected officials of Hispanic origin in cities and states, with related demographic data on proportion of Hispanics in the local or state population. This is followed by information on Hispanics' achievements in sports and by miscellaneous facts of interest about Hispanics. -

WEAI Program 2010-FINAL.Pub

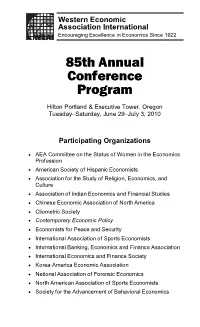

Western Economic Association International Encouraging Excellence in Economics Since 1922 85th Annual Conference Program Hilton Portland & Executive Tower, Oregon Tuesday–Saturday, June 29–July 3, 2010 Participating Organizations • AEA Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession • American Society of Hispanic Economists • Association for the Study of Religion, Economics, and Culture • Association of Indian Economics and Financial Studies • Chinese Economic Association of North America • Cliometric Society • Contemporary Economic Policy • Economists for Peace and Security • International Association of Sports Economists • International Banking, Economics and Finance Association • International Economics and Finance Society • Korea-America Economic Association • National Association of Forensic Economics • North American Association of Sports Economists • Society for the Advancement of Behavioral Economics START OR RENEW YOUR MEMBERSHIP TODAY! Western Economic Association International membership offers all of these great benefits... • Individual subscriptions to both • Reduced submission fee for your quarterly journals, Economic Inquiry individual paper submitted for and Contemporary Economic Policy presentation at either conference if (includes full collection online). you choose not to organize a • Reduced registration fees for the session. Annual Conference and for the • Manuscript submission fee is Biennial Pacific Rim Conference. waived for submitting your • Opportunity to organize your own conference paper to EI or CEP if sessions for both conferences with you do so within six months after the submission fees waived for all conference. included papers. • Reduced EI and CEP manuscript • Complimentary conference regis- submission fees for non- tration for either or both conference manuscripts. conferences if you are an • Discount on International Atlantic Institutional Member affiliate and Economic Society membership. organize a session. -

Leary Rehashes Algeria Shield Laws May Be Disputedin Iranian Case

vol. 23 no. 71 califomia state unhwrsity -J northridge, cafifomia thursday, feb. 22, 1979 Leary rehashes ¥ iJllg**^^* Algeria This is the second of a three- Q. In "Jan Notes" yea faH part biterview Opfaikw Editor dicate that year idea of a new Jim Oberman coadacted with world viskm weald consist of Timothy Leary. Oie '88s drag Bnckmtaster Fuller, Geae cultist. last week. The text of McCarthy. Joba LeaaaB. the biterview has been edited Eldridge Cleaver and Abby •<> only for pertinence and clarity. Hoffman on the same island forming a natural government. Q. When you escaped from prison In 1870 you went to A. Did I say that? Algeria and received political asyhim. Then Eldridge Cleaver Q. Yes yon did, hi your book. put yon under house arrest for revisionism. Whst was the A. Oh my God, 1 deny it. nature of your disagreement That's a CIA reprint, (laughter) with Cleaver? Q. De yea StiU beHeve that? A. Cleaver and I are just Residents Elizabeth Irons and Robert thridge Campus Residence dorms. about in total (q>position in A. (more laughter) I don't Rothrock take time to relax in the Nor (Sundial photo by Kevin Blount) every respect, although I even believe I wrote it respect him and actually like hun a lot. We're actually good Q. WeB. what ceastltates a Students say dorm life bearable, friends. natural government? Q. Name some of the areas A. Genetic gene-|voa(s. where yen disagree with him. but music, menus present problem Q. Coald yea elaborate em A. Well Eldridge is basically that? By KEVIN BLOUNT at a predominantly commuting access to the rooms. -

Thank the Voters of Manchester

28 — MANCHESTER HERALD, Wednesday, Nov, 16, 1983 'J.'; -J ■> 1 Thomas plans to break ‘Old’ kids worry ^ Store brands race’s Irish Connection pediatric experts low In quality? ... page 18 REAL ... page 15 ... p a g e 11 ■ t ESTATE Manchester, Conn. Clearing tonight; Thursday, Nov. 17, 1983 Horr>e o( Ihe We«k tt tpontorad by lh« M cnchM (*r Herald sunny Friday Single copy; 25C MANCHESTER $550,000.00 — See page ^ H r r a lb One story Contemporary Professional Build ing, 8000 Sq. Ft., built 1978, 2+ across w/ame- HOME slte Parking Area for 30+ cars, full basement, t : 240 Ft. Frontage. Oil fired, hot water Heat, Beddawl camp lost separate Air Condition system. Security Sys tem, quick a c c e ss to Exit 94, I-86. OF THE Call and ask for Peter Miller or Ginger Street at 872-7777. Arafat forces ^ Merrill Lynch SSi Realtv WEEK try to escape — K-Mart Plaza, 295 Hartford Tpke. Vernon 872-7777 TRIPOLI, Lebanon (U PI) — Some Arafat called on his followers to cease 600 guerrillas loyal to Palestinian fire but no cease-fire took hold. leader Yasser Arafat launched a "The battle with Arafat is finished counterattack today in an desperate and so is Arafat," said Ahmed Jebril, bid to break out of the Beddawi refugee leader, of the Popular Front for the camp as Syrian-backed Palestinian Liberation of Palestine-General Com 156 E Center St rebels moved in. mand. one of the leaders of a Manchester •6-month-old guerrilla rebellion against Lebanese security sources said at Arafat. -

Name: Carlos Zarate Career Record: Click Alias: Cañas Nationality

Name: Carlos Zarate Career Record: click Alias: Cañas Nationality: Mexican Birthplace: Tepito, Mexico Hometown: Mexico City, Distrito Federal, Mexico Born: 1951-05-23 Stance: Orthodox Height: 5′ 8″ Manager: Cuyo Hernandez Trainer: Jorge Zarate Carlos Zarate Serna (born May 23, 1951) in Tepito, Distrito Federal, Mexico, and better known in the world of boxing plainly as Carlos Zarate, has the distinction of being the only boxer in history to put together two streaks of 20 or more knockout wins in a row. Zarate, considered along with rival Wilfredo Gomez to be among the best punchers in the history of boxing, and probably the two best punchers in the lighter divisions, had an amateur record of 33 wins and 3 losses, with 30 knockout wins, and he won the Mexican Golden Gloves, or Guantes De Oro, in 1969. In 1970, Carlos made his professional debut with a 2 round knockout win over Luis Castaneda in Cuernavaca. That marked the beginning of a 23 fight knockout winning streak. The only boxers to get past the third round during that streak were Al Torres and Antonio Cataneda, who lasted 5 ad 9 rounds respectively, both at Tijuana. Victor Ramirez became the first boxer to last the distance with Zarate when Zarate beat him on points in January of 1974 in Mexico City over ten rounds. Next began his second 20 plus knockout wins in a row streak, when none of his next 28 opponents heard the final bell on their feet. After knocking out former world title challenger Nestor Jimenez in two rounds at Mexicali to end 1975, the WBC made Zarate their number one challenger at the Bantamweight division. -

House Proposes Ending Economic Sanctions Against Rhodesia

House proposes ending economic sanctions against Rhodesia WASHINGTON (AP) -- The House approved House did not insist, as the Senate Prime Minister Ian Smith on Rhode- diplomat Orlando Letelier. a $1 billion foreign military aid did, that Rhodesia also enter an sia's four-man Executive Council, The amendment carrying that pro- bill yesterday after adopting an "all parties" peace initiative aimed the Reverend Ndabaningi Sithole, vision was sponsored by Congressman amendment for lifting U.S. economic at ending the African nation's war joined in pledging the elections will Tom Harkin, D-Iowa. sanctions against Rhodesia. with Black Nationalist guerrillas. be held in December, as scheduled. The sanctions would be repealed Also, the Senate measure did not de- In approving the foreign military It was passed by voice vote, but at the end of this year only if, by mand that a new Salisbury government aid bill, the House did an about-face several hours later a roll call vote then, Rhodesia has installed has in- first must be installed. Its bill concerning Chile. was ordered and the House balloted stalled a new government chosen in called only for "clear progress" to- It first approved, and later re- 243-166 against using arms aid to free elections. ward black-majority rule. jected, an amendment that would have, force extradition of the trio. The vote on the overall aid bill Meanwhile, two members of Rhode- provisionally, cut off all U.S. arms Chile's President Augusto Pinochet was 255-156. The Rhodesian amend- sia's transition government declared shipments to the Santiago government. -

Fear and Nukes on the Campaign Trail by John

Fear and nukes on the Campaign trail by John laForge the Fbi’s pursuit oF saul landau by david priCe exeCuting sheikh nimr by JenniFer loewenstein liFe in a Cage by John CoChran why is the market going Crazy? by mike whitney TELLS THE FACTS AND NAMES THE NAMES VOLUME 22 NUMBER 10, 2015 22 AND NAMES THE VOLUME THE FACTS TELLS Contact Information Subscriptions CounterPunch Business Office 1- year print edition $55 www.counterpunch.org PO Box 228, Petrolia, CA 95558 1- year digital edition (PDF) $35 CounterPunch Magazine , Volume 22, Toll Free 1 (800) 840-3683 1- year print & digital edition $65 (ISSN 1086-2323) is a journal of progres- 1 (707) 629-3683 1- year institutions/supporters $100 sive politics, investigative reporting, civil editorial: 1- year print for student/low income $45 liberties, art, and culture published by The 1-year digital for student/low income $30 Institute for the Advancment of Journalis- [email protected] tic Clarity, Petrolia, California, 95558.Visit business: [email protected] All subscription orders must be pre- counterpunch.org to read dozens of new subscriptions and merchandise: paid — we do not invoice for orders. Renew articles daily, purchase subscriptions, or- [email protected] by telephone, mail, or on our website. der books, plus access 18 years of archives. For mailed orders please include name, address and email address with payment, Submissions or call Periodicals postage pending at Eureka, CounterPunch accepts a small number of 1 (800) 840-3683 or 1 (707) 629-3683. California. submissions from accomplished authors Add $20.00 per year for subscriptions POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: and newer writers. -

Subgroup I. Photographs Series 1. Hank's Files Box 1. a Folder 1. Ab

Subgroup I. Photographs Series 1. Hank’s Files Box 1. A Folder 1. Ab - Ag Kenny Abbott, Raul Abadeljo, Mohammed Abdeen, David Abella, Jimmy Abeyta, Perry “Lil” Abner, Bolden Abrams, Frankie Abrams, Louis Acaries, Carmelo Acevedo, Pablo Acevedo, Israel Acosta, Jorge Acosta, Luis Acosts, Gilberto Acuna, Steve Aczel, Mike Adame, Jimmy Adamick, Albert Adams, Jay Adams, Joe Louis Adams, Keith Adams, Freddy Addeo, Larry Adkins, Jamal Adnan, Eddie Agin, Pedro Agosto, Juan “Mendoza” Aguilar, Danny Aguilera, Raul Aguirre, Rodrigo Aguirre Folder 2. Ah - Alf Jorge Ahumada, Billy Aird, Virgil Akins, Paul Alba, Howie Albert, Johnny Alberts, Jackie Aldare, Don Alderson, Godfrey Alexander, Joe Alexander, Larry Alexander, Mike Alfano, Nelson Alfonso, Bobby Alford, Johnny Alford, Roberto Alfaro Folder 3. Ali - Ame Bash Ali, Rahaman Ali, Rasheed Ali, Unknown Ali, Bob Albright, Bobby Allen, Les Allen, Lloyd Allen, Red Allen, Willie Allen, Terrence Alli, Barry Allison, Love Allotey, Chucho Almazan, Stan Almond, Gilberto Almonte, Tony Alongi, Tato Alonso, Leo Alonzo, Richie Alvarado, Manolo Alvarez, Roman Alvarez, Carlos Amaya, Lou Ambers, Malcolm Ames Folder 4. Amp - Ango Jorge Amparo, Don Amarosa, Davidson Andeh, Brian Anders, Buddy Anderson, Cliff Anderson, Jay Anderson, Lee Anderson, Ray Anderson, Tommy Anderson, Cisco Andreade, Manuel Andrade, Al Andrews, Paul Andrews, Reg Andrews, Valmore Anez, Mick Angel, George Angelo, Sammy Angott, Sammy Angott Folder 5. Angu - Arc Bobby Angus, Hal Anspach, Tony Anthony, Vito Antuofermo, Paris Apice, Fred Apostoli, Red Applegate, Lupe Aquino, Art Aragon, Pasqual “Macho” Aranda, Bruno Arcari, Ray Arcel, Jimmy Archer, Joey Archer, Joey Archibald, Fidel Arciniega Folder 6. Are - Armstrong, Henry Augie Arellano, Argentinian Team, Richard Argo, Baby Arizimendi,George Arkakos, Roone Arledge, Richard Armah, Maurice Armault, Paul Armstead, Bob Armstrong, Davey Armstrong (Ft. -

Gftossmfin's Feeling of Brotherhood Bhngs Into Your Home Septic Woes Rn(J^Evnns P R O D U C T S Com Prnv Pag« 3 Page 11

«» - MANCHESTER HERAl^,Thursday, Sept. 1, 1983 Manchester celebnte$ Whdt your cable dollar Andover lake GFtossmfin's feeling of brotherhood bHngs Into your home septic woes Rn(J^Evnns p r o d u c t s com PRnv pag« 3 page 11 ... page 7 Open Labor Day, Monday September 9:00 AM to 1:00 PM Fair tonight; Manchester, Conn. Friday, Sept. 2,1983 hot, 81Bbnny Saturday Single copy: 254 -^See page 2 mianrhpHtf r He ralJi Soviets say it was Just an ‘accident’ Bv United Press International the embassy statement said. In Tokyo, Soviet AmbassaDor ^Japanese anD Soviet ships For Connecticut reac VlaDimir Pavlov told Japanese search^ toDay for the wreckage of tion, see page 2. officials the Russians haD DetecteD a Korean airliner shot down with “signs" of a downed aircraft near 289 people aboarD by a Soviet Sakhalin IslanD about 785 miles 0 \N fighter in a” unbelievably bar In Moscow, the Soviet govern northwest of the Japanese capital. baric act” conDemneD worldwide. ment kept a stony silence on the Pavlov did not identify the plane The Soviets calleD the plane's loss fate of the Boeing 747 but its as the Korean Air Lines passenger an "acciDent.” embassy in France conDemneD as jet, but the location coinciDeD with There were no known survivors “absolutely unacceptable” the the Boeing 747's position when it among the 240 passengers anD “hysterical anti-Soviet campaign” vanisheD from Japanese raDar 2 crew of 29. by Western governments. screens at 2:26 p.m. EDT Amid angry congressional De “It is a matter of an acciDent WednesDay.