Rewriting the Overtime Dialogue: Why Misclassified Reality Television Producers Are Entitled to Only Half-Time Damages Danielle C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

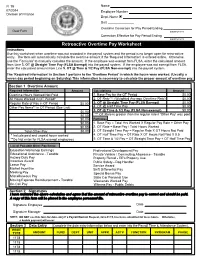

Retroactive Overtime Pay Worksheet

FI 19 Name 07/2014 Employee Number Division of Finance Dept. Name Unit Overtime Correction for Pay Period Ending MM/DD/YYYY Correction Effective for Pay Period Ending MM/DD/YYYY Retroactive Overtime Pay Worksheet Instructions Use this worksheet when overtime was not recorded in the payroll system and the period is no longer open for retro-active entry. The form will automatically calculate the overtime amount if the 'Required Information' is entered online. Otherwise, use the 'Formulas' to manually calculate the amount. If the employee was exempt from FLSA, enter the calculated amount from Line 3. OT @ Straight Time Pay (FLSA Exempt) into the payroll system. If the employee was not exempt from FLSA, enter the calculated amount from Line 5. OT @ Time & 1/2 Pay (FLSA Non-exempt) into the payroll system. The 'Required Information' in Section 1 pertains to the 'Overtime Period' in which the hours were worked. (Usually a seven day period beginning on Saturday) This information is necessary to calculate the proper amount of overtime pay. Section 1 Overtime Amount Required Information Amount Calculations Amount Overtime Hours Worked Not Paid 1. Base Pay for the OT Period All Hours Worked in OT Period* 2. OT Rate*** (Weighted Average Overtime Rate) Regular Rate of Pay in OT Period 3. OT @ Straight Time Pay (FLSA Exempt) Other Pay Items** in OT Period (See List): 4. OT @ Half Time Pay 5. OT @ Time & 1/2 Pay (FLSA Non-exempt) *** OT Rate is greater than the regular rate if 'Other Pay' was paid Formulas 1. Base Pay = Total Hrs Worked X Regular Pay Rate + Other Pay 2. -

Oregon Statewide Payroll Application ‐ Paystub Pay and Leave Codes

Oregon Statewide Payroll Application ‐ Paystub Pay and Leave Codes PAYSTUB PAY AND LEAVE CODES Pay Type Code Paystub Description Detail Description ABL OSPOA BUSINESS Leave used when conducting OSPOA union business by authorized individuals. Leave must be donated from employees within the bargaining unit. A donation/use maximum is established by contract. AD ADMIN LV Paid leave time granted to compensate for work performed outside normal work hours by Judicial Department employees who are ineligible for overtime. (Agency Policy) ALC ASST LGL DIF 5% Differential for Assistant Legal Counsel at Judicial Department. (PPDB code) ANA ALLW N/A PLN Code used to record taxable cash value of non-cash clothing allowance or other employee fringe benefit. (P050) ANC NRS CRED Nurses credentialing per CBA ASA APPELATE STF Judicial Department Appellate Judge differential. (PPDB code) AST ADDL STRAIGHTTIME Additional straight time hours worked within same period that employee recorded sick, holiday, or other regular paid leave hours. Refer to Statewide Policy or Collective Bargaining Agreement. Hours not used in leave and benefit calculations. AT AWARD TM TKN Paid leave for Judicial Department and Public Defense Service employees as years of service award. (Agency Policy) AW ASSUMED WAGES-UNPD Code used to record and track hours of volunteer non-employee workers. Does not VOL HR generate pay. (P050) BAV BP/AWRD VALU Code used to record the taxable cash value of a non-cash award or bonus granted through an agency recognition program. Not PERS subject. (P050 code) BBW BRDG/BM/WELDR Certified Bridge/Boom/Welder differential (PPDB code) BCD BRD CERT DIFF Board Certification Differential for Nurse Practitioners at the Oregon State Hospital of five percent (5%) for all Nurse Practitioners who hold a Board certification related to their assignment. -

Regulations Part 778: Overtime Compensation

Regulations Part 778: Overtime Compensation Title 29, Part 778 of the Code of Federal Regulations U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division WH Publication 1262 (Reprinted May 2011) Material contained in this publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced fully or partially, without permission of the Federal Government. Source credit is requested but not required. Permission is required only to reproduce any copyrighted material contained herein. This material may be contained in an alternative Format (Large Print, Braille, or Diskette), upon request by calling: (202) 693-0675. Toll-free help line: 1-866-487-9243 (1-866-4-USWAGE) TTY TDD* phone: 1-877-889-5627 *Telecommunications Device for the Deaf. Internet: www.wagehour.dol.gov PART 778—OVERTIME COMPENSATION § 778.121 Commission payments—delayed credits and debits. Section Contents § 778.122 Computation of overtime for commission employees on established basic rate. Subpart A—General Considerations Subpart C—Payments That May Be Material contained in this publication is in § 778.0 Introductory statement. Excluded From the “Regular Rate” the public domain and may be reproduced § 778.1 Purpose of interpretative bulletin. fully or partially, without permission of the § 778.2 Coverage and exemptions not discussed. The Statutory Provisions Federal Government. Source credit is requested § 778.3 Interpretations made, continued, and but not required. Permission is required superseded by this part. § 778.200 Provisions governing inclusion, exclusion, only to reproduce any copyrighted material § 778.4 Reliance on interpretations. and crediting of particular payments. contained herein. § 778.5 Relation to other laws generally. § 778.6 Effect of Davis-Bacon Act. -

B-201250,B-201252,B-203524,B

U - ~~~~ / ~~ 0?~/~' THE COMPTRO ER GENERAL DECISION & |FO THE UNITED STATES WASHINGTON, D. C. 20548 FILE: B-201252, B-201250, DATE: September 22, 1981 B-203524, and B-204298 MATTER OF: James Jones, et al. - Overtime pay - Evidence to support claim DIGEST: In the absence of official records, claimsI of Army employees for overtime pay may be paid under best available evidence rule to the extent that the work schedules substan- tiate the employees' claims. The issue presented here is whether the evidence submitted by 22 employees of the Food Service Division, Womack Army Hospital, Fort Bragg, North Carolina, for overtime pay, for the years prior to 1975, is suffi- cient to support their claims. For the reasons set forth below, we hold that the evidence is sufficient to support payment of the claims. These claims arose out of our decision, Council and Washburn, 58 Comp. Gen. 347 (1979), in which we held that these same employees who frequently worked two 8-hour shifts within a 24-hour period, but not within the same calendar day, were entitled to over- time compensation for work in excess of 8 hours during the "day" which was defined in the collective-bargain- ing agreement. The record showed that since 1968 the Food Service Division scheduled its employees on an "early/late" tour of duty involving two overlapping shifts, 0500 to 1330 and 1100 to 1930 daily. It was determined that approximately four times per pay period, employees who worked the 1100 to 1930 shift one day would work the 0500 to 1330 shift the fol- lowing day. -

2019 Status Report on Trafficking in Human Beings in the Czech Republic

2019 STATUS REPORT ON TRAFFICKING IN HUMAN BEINGS IN THE CZECH REPUBLIC Crime Prevention Department Prague 2020 1 ObsaH: INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 3 1. OVERVIEW OF THE CURRENT SITUATION AND TRENDS ................................................. 4 2. CRIMINAL STATISTICS ......................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Number of detected crimes ........................................................................................ 5 2.2. Perpetrators in criminal proceedings ........................................................................ 5 2.3 Selected case studies ................................................................................................ 6 2.4 Victims of trafficking in human beings........................................................................ 6 2.4.1 Victims in criminal proceedings ........................................................................... 6 2.4.2 Potential victims and the Program for the Support and Protection of Victims of Trafficking in Human Beings ........................................................................................ 7 2.5 Care for victims of trafficking in human beings .......................................................... 7 3. RELATED CRIME AND ACCOMPANYING PHENOMENA ..................................................... 8 3.1 Situation in the area of prostitution ........................................................................... -

Terms Used on the Leave and Earnings Statement

TERMS USED ON THE LEAVE AND EARNINGS STATEMENT ITEM TERMS MEANING Item 10 FLSA CATEGORY E=An FLSA exempt employee is one who is not covered by the minimum wage and overtime provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA or Act) N=An FLSA nonexempt employee is one who is covered by the minimum wage and overtime provisions of the Act. Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) Fact Sheet (NIH Only) Item 11 SCD LEAVE Service Computation Date used for annual leave accrual purposes Item 12 MAX LEAVE CARRY OVER Maximum hours of annual leave that you can carry over to the next year Item 13 LEAVE YEAR END The last day of the current leave year Item 14 FINANCIAL INSTITUTION - NET PAY Where your salary payment is deposited Item 15 FINANCIAL INSTITUTION - ALLOTMENT #1 The institution where your allotment is deposited Item 16 FINANCIAL INSTITUTION - ALLOTMENT #2 The institution where your allotment is deposited Item 17 • TAX • Line 1 contains “FED” for Federal tax; Line 2 contains state taxes currently being • MARITAL STATUS withheld, if applicable • EXEMPTIONS • M= Married; S= Single • ADDL • Reflects the number of exemptions you chose • Additional withholding you elected, if any Item 18 • TAX City, county, or other local tax information • MARITAL STATUS • Code identifying the taxing authority • EXEMPTIONS • M= Married; S= Single • ADDL • Reflects the number of exemptions you chose • TAXING AUTHORITY • Additional withholding you elected, if any Note: This block is normally blank Item 19 CUMULATIVE RETIREMENT Reflects your contributions to your retirement -

Randall C. Schauer Partner

Randall C. Schauer Partner [email protected] Exton, PA Tel: 610.458.4967 Fax: 610.458.7337 Randy's practice focuses on all aspects of labor relations and employment law. He handles the full spectrum of the employment relationship from pre-hire procedures to post-termination closure, including unemployment compensation and statutory compliance issues such as Title VII, ADA, FLSA, FMLA and OSHA compliance. Randy negotiates, drafts, and enforces contracts protecting client's rights in all aspects of the employment relationship, including employment and separation, confidentiality and non-competition, intellectual property protection, and independent contractor arrangements. On the labor side, Randy has negotiated Collective Bargaining Agreements and has represented management in grievance arbitrations. He also counsels employers on union avoidance strategies and tactics. He has also successfully served as a private mediator to parties involved in employment disputes. Randy has extensive litigation experience and has successfully tried numerous jury and bench trials to verdict, including injunctive relief. He has been lead defense counsel in several collective actions under the FLSA. He has argued appeals before all Pennsylvania appellate courts, as well as the Third and Fourth Federal Circuit Courts of Appeals. Randy has represented employers before various administrative agencies such as the EEOC, the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission, OSHA, and the NLRB, among others. Services • Labor & Employment • Cannabis Law • Class Actions • Employment Class Actions • Employment Counseling, Policy Development & Audits • Employment Litigation • Employment Training • Sexual Harassment Prevention Training • Wage & Hour Law • Workplace Safety & Health • Property Tax Before Fox Rothschild Randy returned to Fox Rothschild after having served as Chair of the Labor & Employment Group at another large area law firm. -

Payroll Compliance & the Fair Labor Standards Act Post Flores

Payroll Compliance & The Fair Labor Standards Act Post Flores League of California Cities Municipal Finance Institute | December 13, 2018 Presented by: Richard Bolanos and Nicholas Briscoe Payroll Compliance & The Fair Labor Standards Act Post Flores League of California Cities Municipal Finance Institute | December 13, 2018 Presented By: Richard Bolanos and Nicholas Briscoe Agenda • Basic Requirements of FLSA • Common Payroll System Errors • Critical FLSA Compliance Considerations • Tips for Success 2 #1 Take-Away From This Presentation Do Not Rely On a Payroll Vendor for Public Sector FLSA Compliance Expertise – Develop agency’s FLSA concerns and present them to your vendor at the outset – Build in time to test new system on the proposed solutions to your areas of concern – Ultimately, the agency has the legal responsibility to ensure FLSA compliance 3 Basic Requirements of FLSA Basic Requirements of FLSA • Pay minimum and overtime wages when due – “Straight time” for every hour actually worked up to maximum hours threshold – 1.5 x the regular rate for hours actually worked in excess of OT threshold – Wages are due on the regularly scheduled pay day – Late payment = failure to pay – FLSA compensation owed is measured on a workweek / work period basis (no offsetting) 5 Basic Requirements of FLSA • For a payroll system to pay minimum and overtime FLSA wages when due, it must – Accurately measure hours worked – Measure overtime hours on a workweek / work period basis – Correctly calculate and pay overtime compensation due 6 Common Payroll -

Strategy & Insights

Strategy & Insights Energy Employment Law Group Guidance For Employers In The Energy Industry To Avoid Common Wage & Hour Traps Through aggressive investigation and enforcement initiatives, the Department of Labor has recently intensified its scrutiny of employers in the oil-and-gas industry. Among other things, the DOL is looking for employees who have been misclassified as independent contractors, while inspecting employers’ pay practices to ensure compliance with the often-Byzantine wage-and-hour laws. These investigations have resulted in some employers paying large settlements to the DOL (while enjoying unwanted media attention). Even if they don’t involve your company directly, that can make your business sector—and thus your company—a target for private collective- or class-action lawsuits. To avoid these risks and ensure compliance, you need to know about three wage-and-hour traps that are common in the energy industry. TRAP NO. 1: FAILING TO PAY OVERTIME ON TOP OF DAY RATES AND SHIFT RATES Day-Rate Plans Come With a Common and Costly Wage-and-Hour Trap Day-rate plans are common in the oil-and-gas industry. Mud-logging technicians, riggers, roughnecks, welders, and various other craft workers are often paid a fixed sum for each 10-, 12-, or 24-hour shift. But many employers mistakenly believe that paying their nonexempt employees a fixed day or shift rate eliminates the need to track hours or to pay overtime compensation. This is a common wage-and-hour trap. Failing to identify and remedy this frequent mistake will make your company a potential target for class- or collective-action lawsuits and costly investigations by the DOL. -

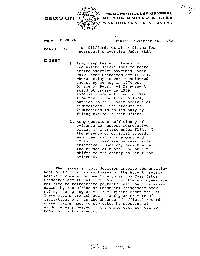

B-208628 [Claims for Retroactive Overtime Under Federal Labor

c FILE: B-208268 DATE: November 16, 1982 MATTER OF: Jon Clifford, --et al. - Claims for Retroactive Overtime Under FLSA DIGEST: 1. Army disputes entitlement of recruiting specialists to retro- active overtime payments under Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). Where employees were considered exempt by agency in 1974 but Office of Personnel Management ruled otherwise in 1979, employees are entitled to over- time pay retroactive to 1974, subject to the 6-year statute of limitations. The statute of limitations is tolled only by filing claims in this Office. 2. Army questions sufficiency of evidence to support retroactive claims of overtime under FLSA. In the absence of official records, employee must show amunt and extent of overtime by reasonable inference. Once employee has met the burden of proof, the burden shifts to the agency to rebut the evidence. The issues in this decision involve the entitle- ment of 17 civilian employees of the Army to retro- active payments for overtime under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). We hold that t5e employees are entitled to retroactive payrents based on a deterrci- nation by the Office ~f Personnel Management over-' ruling the agency on their exemption under the FLSA. These claims are subject to a 6-year statute of limitations and, in the absence of official records, these claims must be supported by scbstantlal evidence as provided by the enployees, subject to rebuttal by the agency. B-208268 BACKGROUND This decision is in respohse to a request from Major P. R. Bergeron, Finance and Accounting Officer, Headquarters Fort Devens, Department of the Army. -

A GUIDE to the HUMAN RESOURCE BODY of KNOWLEDGETM (Hrboktm) WEBFFIRS 04/03/2017 18:59:21 Page Ii WEBFFIRS 04/03/2017 18:59:21 Page Iii

WEBFFIRS 04/03/2017 18:59:21 Page i A GUIDE TO THE HUMAN RESOURCE BODY OF KNOWLEDGETM (HRBoKTM) WEBFFIRS 04/03/2017 18:59:21 Page ii WEBFFIRS 04/03/2017 18:59:21 Page iii AGUIDETOTHE HUMAN RESOURCE BODY OF KNOWLEDGETM (HRBoKTM) SANDRA M. REED, SPHR WEBFFIRS 04/03/2017 18:59:21 Page iv Cover design: Wiley Cover image: naqiewei/Getty Images Copyright 2017 by Human Resources Certification Institute, Inc. All rights reserved. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. Published simultaneously in Canada. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright. com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at www.wiley.com/ go/permissions. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. -

Mr. Paul Decamp Administrator Wage and Hour Division United States Department of Labor 200 Constitution Avenue, N.W., Room S-3502 Washington, D.C

Writer's Direct Dial: (404) 240-4257 Writer's E-mail: [email protected] February 27, 2007 Mr. Paul DeCamp Administrator Wage and Hour Division United States Department of Labor 200 Constitution Avenue, N.W., Room S-3502 Washington, D.C. 20210 Re: Request for Opinion Dear Mr. DeCamp: We request your opinion regarding the calculation of Fair Labor Standards Act overtime premium under the circumstances described in this correspondence. A. FACTUAL BACKGROUND An employer has for some time considered certain of its employees to qualify for the executive exemption, the administrative exemption, or the professional exemption provided for in the FLSA's Section 13(a)(1), 29 U.S.C.A. § 213(a)(1). At all times, the employer has paid each of these employees on a "salary basis" within the meaning of 29 C.F.R. § 541.602. In every instance, each such employee's salary has exceeded the minimum figure necessary to support his or her exempt status. These employees are expected to work at least 50 hours a week. Employees treated as exempt are paid bi-weekly. To facilitate the underlying calculation, the employer's payroll software breaks each employee's bi-weekly salary down to an hourly rate by dividing it by [(50 hrs. × 52 wks.) ÷ 26] = 100. This is done without regard to whether the employee has in fact worked more or less time than 100 hours in the bi-weekly period. For example, if an employee's bi-weekly salary is $1,825.50, the software converts his or her salary to an hourly rate of ($1,825.50 ÷ 100) = $18.255.