Laid Bare in the Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information to Users

Alfred Stieglitz and the opponents of Photo-Secessionism Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Zimlich, Leon Edwin, Jr., 1955- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 21:07:09 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/291519 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

Representations of the Female Nude by American

© COPYRIGHT by Amanda Summerlin 2017 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BARING THEMSELVES: REPRESENTATIONS OF THE FEMALE NUDE BY AMERICAN WOMEN ARTISTS, 1880-1930 BY Amanda Summerlin ABSTRACT In the late nineteenth century, increasing numbers of women artists began pursuing careers in the fine arts in the United States. However, restricted access to institutions and existing tracks of professional development often left them unable to acquire the skills and experience necessary to be fully competitive in the art world. Gendered expectations of social behavior further restricted the subjects they could portray. Existing scholarship has not adequately addressed how women artists navigated the growing importance of the female nude as subject matter throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I will show how some women artists, working before 1900, used traditional representations of the figure to demonstrate their skill and assert their professional statuses. I will then highlight how artists Anne Brigman’s and Marguerite Zorach’s used modernist portrayals the female nude in nature to affirm their professional identities and express their individual conceptions of the modern woman. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I could not have completed this body of work without the guidance, support and expertise of many individuals and organizations. First, I would like to thank the art historians whose enlightening scholarship sparked my interest in this topic and provided an indispensable foundation of knowledge upon which to begin my investigation. I am indebted to Kirsten Swinth's research on the professionalization of American women artists around the turn of the century and to Roberta K. Tarbell and Cynthia Fowler for sharing important biographical information and ideas about the art of Marguerite Zorach. -

Anne Brigman Visionary in Modern Photography

ANNE BRIGMAN VISIONARY IN MODERN PHOTOGRAPHY Photographer, poet, critic, and mountaineer, Anne Brigman (1869-1950) is best known for her figurative landscape images made in the Sierra Nevada in the early 1900s. During her lifetime, Brigman’s significance spanned both coasts of the United States. In Northern California, where she lived and worked, she was a leading Pictorialist photographer, a proponent of the Arts & Crafts movement, and a participant in the burgeoning Berkeley/Oakland Bohemian community. On the East Coast her work was promoted by Alfred Stieglitz, who elected her to the prestigious Photo-Secession and championed her as a Modern photographer. Her final years were spent in southern California, where she wrote poetry and published a book of photographs and poems, Songs of a Pagan, the year before she died. This retrospective exhibition, with loans drawn from prestigious private and public collections around the world, is the largest presentation of Brigman’s work to date. ***** The exhibition is curated by Ann M. Wolfe, Andrea and John C. Deane Family Senior Curator and Deputy Director at the Nevada Museum of Art. We thank the following individuals for their scholarly contributions and curatorial guidance: Susan Ehrens, art historian and independent curator; Alexander Nemerov, Department Chair and Carl & Marilynn Thoma Provostial Professor in the Arts and Humanities at Stanford University; Kathleen Pyne, Professor Emerita of Art History at University of Notre Dame; and Heather Waldroup, Associate Director of the Honors College and Professor of Art History at Appalachian State University. ENTRANCE QUOTE Close as the indrawn and outgoing breath are these songs Woven of faraway mountains … and the planes of the sea … Gleaned from the heights and the depths that a human must know As the glories of rainbows are spun from the tears of the storm. -

Research.Pdf (1.328Mb)

VISUAL HUMOR: FEMALE PHOTOGRAPHERS AND MODERN AMERICAN WOMANHOOD, 1860- 1915 A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Meghan McClellan Dr. Kristin Schwain, Dissertation Advisor DECEMBER 2017 © Copyright by Meghan McClellan 2017 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled Visual Humor: Female Photographers and the Making of Modern American Womanhood, 1860-1915 presented by Meghan McClellan, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Kristin Schwain Dr. James Van Dyke Dr. Michael Yonan Dr. Alex Barker To Marsha Thompson and Maddox Thornton ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The difficulty of writing a dissertation was never far from anyone’s lips in graduate school. We all talked about the blood, sweat, and tears that went into each of our projects. What we also knew was the unrelenting support our loved ones showed us day in and day out. These acknowledgments are for those who made this work possible. This dissertation is a testament to perseverance and dedication. Yet, neither of those were possible without a few truly remarkable individuals. First, thank you to all my committee members: Dr. Alex Barker, Dr. Michael Yonan, and Dr. James Van Dyke. Your input and overall conversations about my project excited and pushed me to the end. Thank you Mary Bixby for giving me the “tough love” I needed to make sure I met my deadlines. -

Copyrighted Material

Contents Preface x Acknowledgements and Sources xii Introduction: Feminism–Art–Theory: Towards a (Political) Historiography 1 1 Overviews 8 Introduction 8 1.1 Gender in/of Culture 12 • Valerie Solanas, ‘Scum Manifesto’ (1968) 12 • Shulamith Firestone, ‘(Male) Culture’ (1970) 13 • Sherry B. Ortner, ‘Is Female to Male as Nature is to Culture?’ (1972) 17 • Carolee Schneemann, ‘From Tape no. 2 for Kitch’s Last Meal’ (1973) 26 1.2 Curating Feminisms 28 • Cornelia Butler, ‘Art and Feminism: An Ideology of Shifting Criteria’ (2007) 28 • Xabier Arakistain, ‘Kiss Kiss Bang Bang: 86 Steps in 45 Years of Art and Feminism’ (2007) 33 • Mirjam Westen,COPYRIGHTED ‘rebelle: Introduction’ (2009) MATERIAL 35 2 Activism and Institutions 44 Introduction 44 2.1 Challenging Patriarchal Structures 51 • Women’s Ad Hoc Committee/Women Artists in Revolution/ WSABAL, ‘To the Viewing Public for the 1970 Whitney Annual Exhibition’ (1970) 51 • Monica Sjöö, ‘Art is a Revolutionary Act’ (1980) 52 • Guerrilla Girls, ‘The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist’ (1988) 54 0002230316.indd 5 12/22/2014 9:20:11 PM vi Contents • Mary Beth Edelson, ‘Male Grazing: An Open Letter to Thomas McEvilley’ (1989) 54 • Lubaina Himid, ‘In the Woodpile: Black Women Artists and the Modern Woman’ (1990) 60 • Jerry Saltz, ‘Where the Girls Aren’t’ (2006) 62 • East London Fawcett, ‘The Great East London Art Audit’ (2013) 64 2.2 Towards Feminist Structures 66 • WEB (West–East Coast Bag), ‘Consciousness‐Raising Rules’ (1972) 66 • Women’s Workshop, ‘A Brief History of the Women’s Workshop of the -

One Hundred Drawings One Hundred Drawings

One hundred drawings One hundred drawings This publication accompanies an exhibition at the Matthew Marks Gallery, 523 West 24th Street, New York, Matthew Marks Gallery from November 8, 2019, to January 18, 2020. 1 Edgar Degas (1834 –1917) Étude pour “Alexandre et Bucéphale” (Study for “Alexander and Bucephalus”), c. 1859–60 Graphite on laid paper 1 1 14 ∕8 x 9 ∕8 inches; 36 x 23 cm Stamped (lower right recto): Nepveu Degas (Lugt 4349) Provenance: Atelier Degas René de Gas (the artist’s brother), Paris Odette de Gas (his daughter), Paris Arlette Nepveu-Degas (her daughter), Paris Private collection, by descent Edgar Degas studied the paintings of the Renaissance masters during his stay in Italy from 1856 to 1859. Returning to Paris in late 1859, he began conceiving the painting Alexandre et Bucéphale (Alexander and Bucephalus) (1861–62), which depicts an episode from Plutarch’s Lives. Étude pour “Alexandre et Bucéphale” (Study for “Alexander and Bucephalus”) consists of three separate studies for the central figure of Alexandre. It was the artist’s practice to assemble a composition piece by piece, often appearing to put greater effort into the details of a single figure than he did composing the work as a whole. Edgar Degas, Alexandre et Bucéphale (Alexander and Bucephalus), 1861–62. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, bequest of Lore Heinemann in memory of her husband, Dr. Rudolf J. Heinemann 2 Odilon Redon (1840 –1916) A Man Standing on Rocks Beside the Sea, c. 1868 Graphite on paper 3 3 10 ∕4 x 8 ∕4 inches; 28 x 22 cm Signed in graphite (lower right recto): ODILON REDON Provenance: Alexander M. -

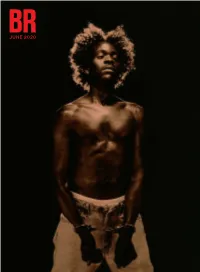

June 2020 June 2020 June 2020 June 2020

JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 field notes art books Normality is Death by Jacob Blumenfeld 6 Greta Rainbow on Joel Sternfeld’s American Prospects 88 Where Is She? by Soledad Álvarez Velasco 7 Kate Silzer on Excerpts from the1971 Journal of Prison in the Virus Time by Keith “Malik” Washington 10 Rosemary Mayer 88 Higher Education and the Remaking of the Working Class Megan N. Liberty on Dayanita Singh’s by Gary Roth 11 Zakir Hussain Maquette 89 The pandemics of interpretation by John W. W. Zeiser 15 Jennie Waldow on The Outwardness of Art: Selected Writings of Adrian Stokes 90 Propaganda and Mutual Aid in the time of COVID-19 by Andreas Petrossiants 17 Class Power on Zero-Hours by Jarrod Shanahan 19 books Weston Cutter on Emily Nemens’s The Cactus League art and Luke Geddes’s Heart of Junk 91 John Domini on Joyelle McSweeney’s Toxicon and Arachne ART IN CONVERSATION and Rachel Eliza Griffiths’s Seeing the Body: Poems 92 LYLE ASHTON HARRIS with McKenzie Wark 22 Yvonne C. Garrett on Camille A. Collins’s ART IN CONVERSATION The Exene Chronicles 93 LAUREN BON with Phong H. Bui 28 Yvonne C. Garrett on Kathy Valentine’s All I Ever Wanted 93 ART IN CONVERSATION JOHN ELDERFIELD with Terry Winters 36 IN CONVERSATION Jason Schneiderman with Tony Leuzzi 94 ART IN CONVERSATION MINJUNG KIM with Helen Lee 46 Joseph Peschel on Lily Tuck’s Heathcliff Redux: A Novella and Stories 96 june 2020 THE MUSEUM DIRECTORS PENNY ARCADE with Nick Bennett 52 IN CONVERSATION Ben Tanzer with Five Debut Authors 97 IN CONVERSATION Nick Flynn with Elizabeth Trundle 100 critics page IN CONVERSATION Clifford Thompson with David Winner 102 TOM MCGLYNN The Mirror Displaced: Artists Writing on Art 58 music David Rhodes: An Artist Writing 60 IN CONVERSATION Keith Rowe with Todd B. -

Anne Brigman ?: a Visionary in Modern Photography Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ANNE BRIGMAN ?: A VISIONARY IN MODERN PHOTOGRAPHY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK A. Wolfe | 400 pages | 24 Nov 2020 | Rizzoli International Publications | 9780847869299 | English | New York, United States Anne Brigman ?: A Visionary in Modern Photography PDF Book Susan Ehrens is an art historian and independent curator. Paul rated it it was ok Jul 29, Kravis II Collection. Details if other :. Throughout her career, she has developed a unique relationship with Sierra Nevada mountains , which were still relatively remote and inaccessible. Featured image: Anne Brigman - Dawn, Although the couple would eventually separate, it is key to understand her experiences of adventure and exploration, which were likely not fully known by her peers. However, these works was never as popular as her earlier style of dramatic pictorialism. Sexton and Mina Turner, by exchange. Rose marked it as to-read Dec 19, A much-anticipated look at one of the first feminist artists, best known for her iconic landscape photographs made in the early s depicting female nudes outdoors in rugged Northern California. For Brigman to objectify her own nude body A much-anticipated look at one of the first feminist artists, best known for her iconic landscape photographs made in the early s depicting female nudes outdoors in rugged Northern California. Back To Top. Brigman began making photographs in , at the age of thirty-two. Log in to leave a comment. Image source: Art Resource, NY. Privacy Connect. Left: Anne Brigman - My Self, not dated. Skip to content. Wolfe is the Andrea and John C. October 4, 5 — 7 pm. For Brigman to objectify her own nude body as the subject of her photographs at the turn of the 20th century was groundbreaking; to do so outdoors in a near-desolate wilderness setting was revolutionary. -

The New Western History & Revisionist Photography

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2000 Parallel tracks| The new Western history & revisionist photography Jonathan Richard Eden The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Eden, Jonathan Richard, "Parallel tracks| The new Western history & revisionist photography" (2000). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3175. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3175 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University oFMONTANA Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature ** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not^ant permission Author's Signature Date 'iL/J S. f Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. PARALLEL TRACKS The New Western History &; Revisionist Photography by Jonathan Richard Eden B.S. The University of Cahfornia at Santa Cruz, 1990 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The University of Montana 2000 Approved by: Chairperson Dean, Graduate School 5 - 5 " <3^000 Date UMI Number: EP36131 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Myra Albert Wiggins (1869-1956) Carole Glauber, ©2001

Trials and Triumphs of an Oregon Photographer: Myra Albert Wiggins (1869-1956) Carole Glauber, ©2001 yra Albert Wiggins invented her life. She did so at an uncanny speed that might have left others breathless. Barely 5'1" tall, she moved in a hurry by running in little steps on her toes; friends had M to keep up with Myra rather than Myra keep up with her friends. During her long life, she was many things: a painter, poet, writer, singer, art and voice teacher, and mentor to artists. Her leadership skills helped launch Women Painters of Washington – a group still active today. So amazing were her accomplishments, that as she approached her 84th birthday, her nephew suggested, “Myra has done everything in her lifetime but jump off the Eiffel Tower and she could probably do that safely if she wanted to.” Myra Wiggins left many legacies, but among the most significant of these were her photographs. Born on December 14, 1869 in Salem, Oregon, the second of four children and the grandchild of Oregon pioneers, Myra’s sense of independence appeared even as a child. Then, Salem had a population of about 1,000, where people traveled by horseback, wagon or river steamer. Even as Salem grew, it was still a small enough town that position and achievements by individuals were noticed and what people did mattered. Myra loved the outdoors and remembered her childhood as “the wild, free, ‘tomboy’ life of a Western Oregon small town girl.” She later wrote that “no boy or man in my hometown could beat me at running.” Her father became president of the Capital National Bank and her mother an art teacher and homemaker. -

The Ecofeminist Lens

The Ecofeminist Lens: Nature, Technology & the Female Body in Lens-based Art Nikki Zoë Omes Nikki Zoë Omes S2103605 Master’s Thesis Faculty of Humanities, Leiden University MA Media Studies, Film & Photographic Studies Supervisor: Helen Westgeest Second Reader: Eliza Steinbock 14 August 2019 21,213 words Contact: [email protected] Cover page collage created by writer. 1 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Chapter 1: Photographic Transitions in Representing the Human-Nature Relation 10 1.1. From Documentary to Conceptual: Ana Mendieta’s Land Art 11 1.2. From Painterly to Photographic: The Female Nude in Nature 17 Chapter 2: The Expanding Moving Image of the Female Body in Nature 27 2.1. From Outside to Inside: Ana Mendieta’s Films in the Museum 28 2.2. From Temporal to Spatial: Pipilotti Rist’s Pixel Forest as Media Ecology 35 Chapter 3: An Affective Turn Towards the Non-human/Female Body 42 3.1. From Passive Spectator to Active Material: The Female Corporeal Experience 43 3.2. From Iconic to Immanent: The Goddess in Movement 49 Conclusion 59 Works Cited 61 Illustrations 68 2 Introduction I decided that for the images to have magic qualities I had to work directly with nature. I had to go to the source of life, to mother earth (Mendieta 70). Ana Mendieta (1948-1985) was a multimedia artist whose oeuvre sparked my interest into researching the intersection between lens-based art and ecofeminism.1 Mendieta called her interventions with the land “earth-body works,” which defy categorization and instead live on within several discourses such as performance art, conceptual art, photography and film. -

Frieze London and Masters Find a Common Future for Contemporary

ARTSY EDITORIAL BY ALEXANDER FORBES OCT 4TH, 2017 7:18 PM critical dialogue and market trends that have increasingly blurred the distinction between "old" and "new." Take "Bronze Age c. 3500 BC-AD 2017," Hauser & Wirth's thematic booth at Frieze London, curated in collaboration with hipster feminist hero and University of Cambridge classics professor Mary Beard, whose fairly tongue-in-cheek descriptions of the works are worth a look. The mock museum brings together historic works by artists like Marcel Duchamp, Louise Bourgeois, and Henry Moore with contemporary artists from the gallery's program (Phyllida Barlow, who currently represents the U.K. at the Venice Biennale, made her first-ever piece in bronze, Paintsticks, 2017, for the occasion). These are interspersed with antiquities Beard helped source from regional museums and around 50 purported artefacts that Wenman bought on eBay. "Part of the irony is that it looks like a Frieze Masters booth," said Hauser & Wirth senior director Neil Wenman. "I wanted to bring old things but the lens is contemporary. It's about the way we look at objects," and how a given mode of display can ascribe value to those objects. The gallery hasn't leveraged the gravitas of its ethnographic museum vitrines to sell Wenman's eBay finds at a steep margin, but it is offering80 artworks for sale (out of the roughly 180 objects on display). For those on a budget, they've also created souvenirs sold from a faux museum gift shop that will run you £ 1-£9; proceeds will go to the four museums that lent pieces for the show.