Archimedes Russell and Nineteenth-Century Syracuse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O R D E R .Of E X E R C I S E S at E X H I B I T I O N

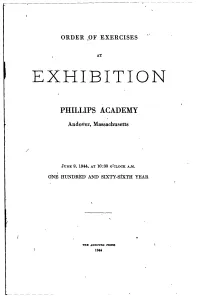

ORDER .OF EXERCISES AT EXHIBITION PHILLIPS ACADEMY AndoVer, Massachusetts / JUNE 9, 1944, AT 10:30 O'CLOCK A.M. ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY-SLXTH YEAR THE ANDOVER PRESS 1944 ORDER OF EXERCISES Presiding CLAUDE MOORE FUESS Headmaster PRAYER REVEREND A. GRAHAM BALDWIN School Minister (Hum Uaune Initiation service of the Honorary Scholarship Society, Cum Laude, with an address by Kenneth C. M. Sills, LL.D., President of Bowdoin College. H&tmbtv* of thr (Elana of 1944 Elected in February HEATH LEDWARD ALLEN THOMSON COOK MCGOWAN JOHN WESSON BOLTON HENRY DEAN QUINBY, 3D CARLETON STEVENS COON, JR. JOHN BUTLER SNOOK JOHN CURTIS FARRAR DONALD JUSTUS STERLING, JR. FREDERICK DAVIS GREENE, 2D WHITNEY STEVENS ALFRED GILBERT HARRIS JOHN CINCINNATUS THOMPSON JOHN WILSON KELLETT Elected in June JOHN FARNUM BOWEN VICTOR KARL KOECHL ISAAC CHILLINGSWORTH FOSTER ERNEST CARROLL MAGISON VICTOR HENRY HEXTER, 2D ROBERT ALLEN WOFSEY DWIGHT DELAVAN KILLAM RAYMOND HENRY YOUNG CHARLES WESLEY KITTLEMAN, JR. £Am\t ANNOUNCEMENT OF HONORS AND PRIZES SPECIAL MENTION FOR DISTINGUISHED SCHOLARSHIP DURING THE SENIOR YEAR BIOLOGY Richard Schuster CHEMISTRY Carleton Stevens Coon, Jr. Ernest Carroll Magison John Curtis Farrar Donald Justus Sterling, Jr. John Wilson Kellett ENGLISH Heyward Isham Donald Justus Sterling, Jr. FBENCH Ian Seaton Pemberton GERMAN Heyward Isham Arthur Stevens Wensinger HISTORY ~John Curtis Farrar Donald Justus Sterling, Jr. Thomson Cook McGowan MATHEMATICS John Farnum Bowen >• Donald Justus Sterling, Jr. Benjamin Yates Brewster, Jr. John Cincinnatus Thompson John Curtis Farrar Robert Allen Wofsey Isaac Chillingsworth Foster Raymond Henry Young John Wilson Kellett PHYSICS John Famum Bowen Charles Wesley Kittleman, Jr. Carleton Stevens Coon, Jr. -

A Brief History of the Passamaquoddy Indians

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Maine The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine History Documents Special Collections 1977 A Brief History of the Passamaquoddy Indians Susan M. Stevens Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory Part of the History Commons This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Revised 1/77 A BRIEF HISTORY Pamp 4401 of the c.l PASSAMAQUODDY INDIANS By Susan M. Stevens - 1972 The Passamaquoddy Indians of Maine are located today on two State Reservations about 50 miles apart. One is on Passamaquoddy Bay, near Eastport (Pleasant Point Reservation); the other is near Princeton, Maine in a woods and lake region (Indian Township Reservation). Populations vary with seasonal jobs, but Pleasant Point averages about 400-450 residents and Indian Township averages about 300- 350 residents. If all known Passamaquoddies both on and off the reservations were counted, they would number around 1300. The Passamaquoddy speak a language of the larger Algonkian stock, known as Passamaquoddy-Malecite. The Malecite of New Brunswick are their close relatives and speak a slightly different dialect. The Micmacs in Nova Scotia speak the next most related language, but the difference is great enough to cause difficulty in understanding. The Passamaquoddy were members at one time of the Wabanaki (or Abnaki) Confederacy, which included most of Maine, New Hampshire, and Maritime Indians. -

A Genealogy of the Lineal Descendants of John Steevens, Who Settled In

929.2 St474h 1727483 REYNOLDS H^^TORICAL GENEALOGY COLLECTION IST-C- ALLEN COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY . 3 1833 01422 5079 I A GENEALOGY OF THE LINEAL DESCENDANTS OF JOHN STEEVENS WHO SETTLED IN GUILFORD, CONN. IN 1645. COMPILED BY CHARLOTTE STEEVENS HOLMES '"""'"""" 1906 EDITED BY CLAY W. HOLMES, A. M., ELMIRA, N. y. <\ t- .^^ ^ Col Te Uni Ki qu Ho th t>. ^<l>^^ . Correction and addition for Steevens (Stevens) Genealogy Lineal Desc^-ndanta of Text: Charlotte ?. Holmes' John SteMVAny """of Gullf'JFd (conn.) Under the llrtlng for^Iarael Etevens b ?ept 7, 1747 m Dec 4, 1771 at Killln^T./orth, farah Keleey b June 21, 1740'"'.. etc. one finds this quotation: "This couple moved to VVllrinc^ton, V/lndharn Co.,Vt., previous to Oct. 17G4 ..," Ko further listing. Ho"ever, search Into Vermont and Mew York State, vital records phows the follo'-ving Inforiration In re^-ard to the* de^cendantp of the couple: 1. Solo:r:on Stevena , ?on of Israel .^r.^ Eapt I'arch 10, 1776 5". Benevolent Stevens, ron of Tnraal, Dant a'ov 5, 17P0 ; n at VHmlnp'ton, Vt., May 5, irOS, Suran, dau of Cnrt. Rob rt :-lunter; he d nt Dryd3n, •N.Y., Sept. 22, 18C4| r.ho d July 2^ , 1P30 at Dryden. He m (2) Betsey, ..'Ido'^v of Ehadrach Tarry of Llple, Bro-^ine Co-.,!'I,Y. l-;>? children. 3. Henry Stevens, son of Israel bar^t Feb 16, 17R3, at K' lllnT-'orthjConn. • n Jorusha Fox; diod Hov. 29, 1632; burl'd in T xas Vall-'-y Cernetery, To-11 of ''arathon, II. -

1 Thomas and Ester/Esther ( ) Stevens of Boston, Massachusetts with Additions and Corrections To

THOMAS AND ESTER /E STHER ( ) STEVENS OF BOSTON , MASSACHUSETTS 1 Copyright 1999 Perry Streeter (Content updated 16 February 2010) © 1999 Perry Streeter @ mailto:[email protected] @ http://www.perry.streeter.com This document is Copyright 1999 by Perry Streeter. It may be freely redistributed in its entirety provided that this copyright notice is not removed. It may not be sold for profit or incorporated in commercial documents without the written permission of the copyright holder. I am seeking all genealogical and biographical details for the family documented below including their ancestors, children, and grandchildren and the spouses thereof, including the full names of those spouses' parents. All additions and corrections within this scope, however speculative, will be greatly appreciated. Thomas and Ester/Esther ( ) Stevens of Boston, Massachusetts with additions and corrections to "Homer-Stevens Notes, Boston" by Winifred Lovering Holman with an emphasis on the family of Thomas and Sarah (Place) Stevens of Boston, Massachusetts * WORK-IN-PROGRESS * CHECK FREQUENTLY FOR UPDATES * FOREWORD The genesis of this chapter was the identification of my probable ancestor, Jane (Stevens) Dyer, as the daughter of Thomas and Sarah (Place) Stevens of Boston (Lora Altine Woodbury Underhill, Descendants of Edward Small [Cambridge, Massachusetts: Privately Printed at The Riverside Press, 1910], 1174, citing Suffolk County, Massachusetts deed 53:41). I was doubtful that the deed explicitly identified Jane as the daughter of Thomas Stevens and I was even more doubtful that the deed identified the maiden name of Jane's mother. In 2009, in response to my posting on this topic on the Norfolk County, Massachusetts RootsWeb.com message board, Erin Kelley graciously agreed to obtain a copy of this deed for me. -

Norcross Brothers Granite Quarry Other Names/Site Number Castellucci Quarry

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places j g Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item be marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable". For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property___________________________________________________ historic name Norcross Brothers Granite Quarry other names/site number Castellucci Quarry 2. Location street & number ___ Quarry Road D not for publication city or town _____ Branford D vicinity state Connecticut code CT county New Haven code 009 zip code 06405 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this 3 nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property IS meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant Dnaticrially Q^tatewide $ locally. -

Lilillliiiiiiiiiiillil COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY of DEEDS

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE M/v p p n.r» ftn p p -h +: p COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Suffolk INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE (lype all entries — complete applicable sections) ^^Pi^^^^^ffi^SiiMliiii^s»^«^^i^ilSi COMMON: •••'.Trv; ;.fY ', ; O °. • ':'>•.' '. ' "'.M'.'.X; ' -• ."":•:''. Trinity Church "' :: ' ^ "' :; " ' \.'V 1.3 ' AND/OR HISTORIC: Trinity EpisQppa^L Church W&££$ii$$®^^ k®&M$^mmmmmmm:^^ STREET AND NUMBER: Boylston Street, at Coplev Sauare CITY OR TOWN: "Rofiton STATE CODE COUNTY: CODE Ma. ft ft an h n ft P i". t s Snffnlk STATUS ACCESSIBLE CATEGORY OWNERSHIP (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC Q District g] Building d P " D| i c Public Acquisition: ^ Occupied Yes: ., . , | | Restricted Q Site Q Structure H Private D 1" Process a Unoccupied ' — i— i D • i0 Unrestricted Q Object D Both D Being Considered [_J Preservation work in progress ' — ' PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) \ I Agricultural | | Government 1 1 Park I | Transportation 1 1 Comments | | Commercial 1 1 Industrial | | Private Residence I"") Other (Specify) | | Educational 1 1 Military [X] Religious | | Entertainment 1 1 Museum | | Scientific ................. OWNER'S NAME: (/> Reverend Theodore Park Ferris, Rector, Trinity Epsicopal Ch'urch STREET AND NUMBER: CJTY OR TOWN: ' STAT E: 1 CODE Boston 02 II1-! I lassachusetts. , J fillilillliiiiiiiiiiillil COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC: COUNTY: Registry of Deeds, Suffolk County STREET AND NUMBER: -

Study Report Proposed H. H. Richardson Depot Historic District Framingham, Massachusetts

Study Report Proposed H. H. Richardson Depot Historic District Framingham, Massachusetts Framingham Historic District Commission Community Opportunities Group, Inc. September 2016 Study Report Proposed H. H. Richardson Depot Historic District September 2016 Contents Summary Sheet ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Public Hearings and Town Meeting ..................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Background to the Current Proposal ................................................................................................ 5 Local Historic Districts and the Historic Districts Act ................................................................... 6 Local Historic Districts vs. National Register Districts .................................................................. 7 Methodology Statement ........................................................................................................................ 8 Significance Statement ......................................................................................................................... 9 Historical Significance ..................................................................................................................... 9 Architectural Description .............................................................................................................. -

Oliver Wendell Holmes Library 151!

OLIVER WENDELL HOLMES LIBRARY 151! PHILLIPS ACADEMY Andover, Massachusetts ORDER OF EXERCISES AT EXHIBITION Friday, June Eleventh Nineteen Hundred Seventy-One One Hundred and Ninety-third Year PROCESSIONALS Trustees and Faculty: AGINCOURT HYMN Dunstable Seniors: THE PHILLIPS HYMN THE NATIONAL ANTHEM INVOCATION JAMES RAE WHYTE, S.T.M. School Minister INITIATION SERVICE OF THE CUM LAUDE SOCIETY ALSTON HURD CHASE, PH. D. President of the Andover Chapter FREDERICK SCOULLER ALLIS, JR., A.M., L.H.D. Secretary of the Andover Chapter The following members of the Class of 1971 were elected in February: JAMES RICHARD BARKER, JR. CHIEN LEE LUIS PALTENGHE BUHLER STANLEY LIVINGSTON, HI DOUGLAS FRANCISCO BUXTON JAMES ELLIOT LOBSENZ PETER DAGGETT EDEN STEPHEN DOMINIQUE PELLETIER NILS CHRISTIAN FINNE ALLAN ANTHONY RAMEY, JR. DAVID MICHAEL GRAVALLESE DAVID FREDERICK ROLL PETER RUDOLPH HALLEY JEFFREY BRIAN ROSEN • GREGG ROSS HAMILTON STEPHEN CARTER SHERRILL ROBERT BICKFORD HEARNE, JR. CHRISTOPHER FORREST SNOW ALAN JOHN KAUFMAN PAUL STERNBERG, JR. CHARLES BAKER KEEFE WILLIAM DOUGLAS WHAM The following members of the Class of 1971 were elected in June: BRIAN HENRY BALOGH GEORGE GARDNER LORING, JR. TIMUEL KERRIGAN BLACK RICHARD DONALD MCLAUGHLIN, JR. PETER COLE BLASIER JOHN STEVENS MINER DAVID BIGELOW DANNER WILLIAM MCGAFFEE MURRAY, JR. PETER WOOD DEWITT JAMES DOUGLAS POST EDWARD DENNIS DONOVAN CHARLES BOOTH SCHAFF, JR. THOMAS COLEMAN FOLEY LINCOLN SMITH JAMESON STEVENS FRENCH PAUL ROGER TESSDJIR WILLIAM PALMER GARDNER JEFFREY LYNN THERMOND TIMOTHY JAMES GAY SETH WALWORTH JOHN WILLIAM GILLESPIE, JR. ETHAN LYMAN WARREN BRADLEY DEWEY KENT ROBERT MILTON WESCHLER ADDRESS TO THE GRADUATING CLASS JOHN MASON KEMPER, A.M., L.H.D., Litt. -

WAKEFIELD Icinity State MASSACHUSETTS Code 025 County Code Zip Code 01880

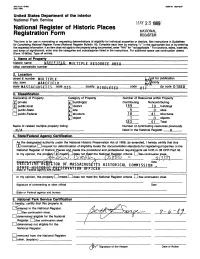

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10244010 (Rav. 846) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Registration Form REGISTER This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name HAKEFJ.&rlL MULTIPLE RESOURCE AREA_________________ other names/site number 2. Location street & number Mill TTPI F ot for publication city, town WAKEFIELD icinity state MASSACHUSETTS code 025 county code zip code 01880 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property private I building(s) Contributing Noncontributing public-local | district 159 buildings public-State I site _ sites I public-Federal | structure 41 structures | object 0 objects Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously N/A listed in the National Register Q_____ 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ffl nomination EU request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Glenn Brown and the United States Capitol by William B

GLENN BROWN AND THE UNITED STATES CAPITOL BY WILLIAM B. BUSHONG HE most important legacy of Washington architect Glenn Brown’s prolific writing career was his two-volume History of the United States Capitol (1900 and 1903). Brown’s History created a remarkable graphic record and comprehensive Taccount of the architecture and art of the nation’s most revered public building. His research, in a period in which few architectural books provided substantive historical text, established Brown as a national authority on government architecture and elicited acclaim from Euro- pean architectural societies. The History also played a significant role in shaping the monumental core of Washington, in effect serving as what Charles Moore called the “textbook” for the McMillan Commis- sion of 1901–02.1 Brown’s family background supplied the blend of political aware- ness and professionalism that inspired the History. His great grand- father, Peter Lenox, supervised construction of the original Capitol Building from 1817 until its completion in 1829. His grandfather, Bed- ford Brown, served two terms in Washington, D.C., as a senator from North Carolina (1829–1842) and counted among his personal friends Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, Franklin Pierce, and James 1 Charles Moore (1855–1942), chief aide to Senator James McMillan (R–MI) and secretary to the now famous Senate Park Commission of 1901–02, commonly referred to today as the McMillan Commission, made vital contributions to the administration and editing of the influential 1902 planning report that subsequently shaped the twentieth- century development of the civic core of Washington, D.C. Moore later became chairman of the United States Commission of Fine Arts from 1910 until his retirement in 1937. -

Summary 1 1. INTRODUCTION A. the City of Worcester Issues This RFQ

1. INTRODUCTION A. The City of Worcester issues this RFQ for the purposes of engaging the services of a qualified professional sculpture conservator or art conservation studio (hereafter identified as the “Conservator” or the “Vendor”) to perform cleaning and conservation of twelve historic objects and monuments within the City of Worcester. B. The following sculptures and monuments are to be conserved/repaired: Wheaton Square (1898) (bronze) Celtic Cross (stone) City Hall Armor (2, metal) City Hall, Deedy Plaque (bronze) City Hall Marble Eagle (2) City Hall Mastrototoro Plaque (bronze) City Hall USS Maine Plaque (bronze) City Hall Norcross Plaque (bronze) City Hall Order of Construction Plaque (bronze) City Hall Ship Bell (bronze) Elm Park Fisher Boy (bronze and stone) Elm Park Winslow Gate (Lincoln Gate) (bronze and natural boulders) C. The Conservator will provide all supplies and materials, site safety materials including signs, caution tape, safety cones, and plastic sheeting. D. The Conservator will provide weekly updates to the project manager. E. Schedule for Work: all work must begin and be completed by dates agreed upon by the selected Conservator and the City of Worcester. F. The Conservator will be responsible for erecting scaffold as needed, and providing ladders as needed, except for historic objects within Worcester City Hall, where the Facilities Department will provide access. 2. REQUIRED SERVICES: PROFESSIONAL ART CONSERVATION TREATMENT A. The Conservator shall implement all conservation services according to the treatments to be carried out according to the Standards for Practice outlined by the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, including: surface cleaning of sculptures and monuments, removal of previous coatings as specified, repatination of bronze to correct historic color, removal of old or Summary 1 inappropriate coatings or over paint, structural repairs as specified, restoration of missing elements as specified in individual reports and with consultation with the project manager. -

Shepley Bulfinch Richardson Abbott: 4 Projects Executive Summary

HARVARD DESIGN SCHOOL version May 4, 2006 Prof. Spiro N. Pollalis Shepley Bulfinch Richardson Abbott: 4 Projects Understanding Changes in Architectural Practice, Documentation Processes, Professional Relationships, and Risk Management Executive Summary This case study analyzes the evolving role of the architect in the construction process through the lens of four projects designed by Shepley Bulfinch Richardson Abbott during the last 125 years. It also addresses the changes in the working relationship of architects with contractors and owners, the quantity and quality of construction documentation architects produce, and the risks to which architects are exposed. Shepley Bulfinch Richardson and Abbott (SBRA) has its origins in the architectural firm founded in 1874 by architect Henry Hobson Richardson. It is one of the oldest continuously operating architectural firms in the United States and has survived the full range of ownership transitions and changes in forms of practice, from sole practitioner, to partnership, and a century later, to corporation in 1972. It weathered the loss of its founder and subsequent family owner-practitioners, to become today one of the nation's largest and most successful architectural firms. The four projects are: • Sever Hall at Harvard University, a classroom building completed in 1880. • Eliot House at Harvard University, a residence hall completed during the Great Depression. • Mather House, at Harvard University, a residence hall completed in the 1970s, and • Hotung International Law Center Building at Georgetown University, a law center and fitness facility completed in 2004. The number of sheets of working drawings in the above projects range from a few to many. The number of pages of specifications varies from a few typed pages to entire manuals.