Teaching Methods for Evidence-Based Practice in Optometry Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evidence Based Answers to Clinical Questions for Busy Clinicians

Evidence-Based Answers to Clinical Questions for Busy Clinicians Workbook Harris C & Turner T 2011 Updated 2018 This publication should be cited as: Harris C & Turner T. Evidence-Based Answers to Clinical Questions for Busy Clinicians. (2011) The Centre for Clinical Effectiveness, Monash Health, Melbourne, Australia. Copyright © This publication is the copyright of Monash Health. Other than for the purposes and subject to the conditions prescribed under the Copyright Act 1968 as amended, no part of this publication may, in any form or by any means (electric, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise), be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to Centre for Clinical Effectiveness. Acknowledgements The authors would like to acknowledge past and present staff of the Centre for Clinical Effectiveness at Monash Health for their contributions towards the development of this resource. Centre for Clinical Effectiveness Monash Health Phone: +61 3 9594 7575 Fax: +61 3 9594 6018 Email: [email protected] Web : www.monashhealth.org/cce Evidence-Based Answers to Clinical Questions for Busy Clinicians Workbook 2 Objectives This workbook aims to help you to find the best available evidence to answer your clinical questions, in the shortest possible time. It will introduce the principles of evidence-based practice and provide a foundation of understanding and skills in: o Developing questions that are answerable from the literature o Searching for and identifying evidence to answer your question o Appraising the evidence identified for quality, reliability, accuracy and relevance Contents page 1. What is evidence-based practice? 4 2. -

Application of the PICO Process to Plan Treatment for a Child with a Co-Occurring Stuttering and Phonological Disorder

Volume 8, Issue 6 March 2014 EBP briefs A scholarly forum for guiding evidence-based practices in speech-language pathology Application of the PICO Process to Plan Treatment for a Child With a Co-occurring Stuttering and Phonological Disorder Keegan M. Koehlinger Linda Louko Patricia Zebrowski EBP Briefs Editor Laura Justice The Ohio State University Associate Editor Mary Beth Schmitt The Ohio State University Editorial Review Board Tim Brackenbury Lisa Milman Bowling Green State University Utah State University Jayne Brandel Cynthia O’Donoghue Fort Hays State University James Madison University Kathy Clapsaddle Amy Pratt Private Practice (Texas) The Ohio State University Lynn Flahive Nicole Sparapani Texas Christian University Florida State University Managing Director Tina Eichstadt Pearson 5601 Green Valley Drive Bloomington, MN 55437 Cite this document as: Koehlinger, K. M., Louko, L., & Zebrowski, P. (2014). Application of the PICO process to plan treatment for a child with a co-occurring stuttering and phonological disorder. EBP Briefs, 8(6), 1–9. Bloomington, MN: Pearson. Copyright © 2014 NCS Pearson, Inc. All rights reserved. Warning: No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without the express written permission of the copyright owner. Pearson, PSI design, and PsychCorp are trademarks, in the US and/or other countries, of Pearson Education, Inc., or its affiliate(s). NCS Pearson, Inc. 5601 Green Valley Drive Bloomington, MN 55437 800.627.7271 www.PearsonClinical.com Produced in the United States of America. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 A B C D E Application of the PICO Process to Plan Treatment for a Child With a Co-occurring Stuttering and Phonological Disorder Keegan M. -

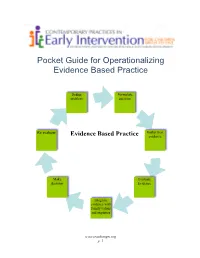

Pocket Guide for Operationalizing Evidence Based Practice

Pocket Guide for Operationalizing Evidence Based Practice Define Formulate problem question Re evaluate Gather best Evidence Based Practice evidence Make Evaluate decision Evidence Integrate evidence with family values and expertise www.teachinngei.org p. 1 Define the Problem When a service provider is attempting to understand a new problem, often their questions are broad making it difficult to gather information to inform decisions. Narrowing the problem to certain element gives the best starting point in a search for evidence. Formulate the Question A well constructed question makes the search for evidence easier and more efficient. A good question should contain the specific group or population, the intervention or issue being addressed/ compared and the desired outcome. Gathering the Best Evidence Many sources of evidence come together to inform decisions made about practice. It is important to have the skills and strategies to make timely and effective decisions. Sources of best evidence include • Information sources: publications, databases, web sites, laws and policies • Service provider experience and expertise • Family values, beliefs, priorities and concerns Information Sources: 1. Publications There are a wide range of publications available with information about practice across disciplines in early childhood. Scholarly publications are the most likely to yield accurate information needed to make decisions. These sources include: o Peer-reviewed journals o Research articles o Guidelines and recommended practices o Systematic reviews and Meta-analysis o Books o Reports o Magazines, non- peer reviewed journals 1a. Peer Reviewed Information Information from peer-reviewed or refereed publications is considered high quality because the process to publish requires the scrutiny of experts in the field as well as scientific methods. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Clinical Judgement in the era of Evidence Based Medicine Flores Sepulveda, Luis Jose Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to: Share: to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Nov. 2017 Clinical judgment in the era of Evidence Based Medicine Submitted to the Department of Philosophy of King’s College London, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of philosophy Luis Flores MD. -

This Is the Title of My Thesis

A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Interventions (Pharmaceutical and Psychosocial) for Cognitive and Learning Impairments in Children Diagnosed with a Brain Tumour Lisa-Jane Keegan Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Clinical Psychology (D. Clin. Psychol.) The University of Leeds School of Medicine Academic Unit of Psychiatry and Behavioural Sciences September 2014 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2014 The University of Leeds and Lisa-Jane Keegan (Optional) The right of Lisa-Jane Keegan to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am sincerely grateful for the help of Professor Stephen Morley and Dr Matthew Morrall, without their support, time and patience this thesis would never have been possible. A big thank you to Miss Rosa Reed-Berendt (Research Assistant), Mr Paul Farrington (Psychologist in Forensic Training), Miss Elizabeth Neilly – Health Faculty Team Librarian, Ms Janet Morton – Education Faculty Team Librarian, Drs Picton, Wilkins and Elliott - Consultant Paediatric Oncologists, Dr Livingston - Consultant Paediatric Neurologist at The Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Miss Helen Stocks, Miss Kate Ablett and Dr Stanley, Consultant Child & Adolescent Psychiatrist, Leeds Community Healthcare NHS Trust, Suzanne Donald (Honorary Research Assistant) and Michael Ferriter- Lead for Research, Forensic Division, Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust; who have supported me to achieve my goal. -

Anesthetic Considerations for the Parturient with Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Levi G

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Nursing Capstones Department of Nursing 7-12-2018 Anesthetic Considerations for the Parturient with Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Levi G. La Porte Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/nurs-capstones Recommended Citation La Porte, Levi G., "Anesthetic Considerations for the Parturient with Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension" (2018). Nursing Capstones. 187. https://commons.und.edu/nurs-capstones/187 This Independent Study is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Nursing at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nursing Capstones by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: SAFETY OF SUGAMMADEX AND NEOSTIGMINE 1 The Safety and Efficacy in Reversal of Neuromuscular Blockades with Sugammadex versus Neostigmine by Nicole L. Landen Bachelor of Science in Nursing, University of Minnesota, 2014 An Independent Study Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Grand Forks, North Dakota December 2019 SAFETY OF SUGAMMADEX AND NEOSTIGMINE 2 PERMISSION Title The Safety and Efficacy in Reversal of Neuromuscular Blockades with Sugammadex versus Neostigmine Department Nursing Degree Master of Science In presenting this independent study in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the College of Nursing and Professional Disciplines of this University shall make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for extensive copying or electronic access for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor who supervised my independent study work or, in her absence, by the chairperson of the department or the dean of the School of Graduate Studies. -

Evidence-Based Practice Special Interest Group Section on Research

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE SPECIAL INTEREST GROUP SECTION ON RESEARCH AMERICAN PHYSICAL THERAPY ASSOCIATION DOCTOR OF PHYSICAL THERAPY EDUCATION EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE CURRICULUM GUIDELINES March 2014 Task Force Chairs: David Levine, PT, PhD, DPT, OCS Julie K. Tilson, PT, DPT, MS, NCS Professor and Walter M. Cline Chair Associate Professor of Clinical Physical Therapy of Excellence in Physical Therapy University of Southern California, The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, Los Angeles, CA Chattanooga, TN Task Force Members: Deanne Fay, PT, DPT, MS, PCS Dianne Jewell, PT, DPT, PhD, FAACVPR Associate Professor and Director of Founder and CEO Curriculum The Rehab Intel Network, Consulting Physical Therapy Program Services, Ruther Glen, VA Arizona School of Health Sciences A.T. Still University, Mesa, AZ Sandra Kaplan PT, DPT, PhD Professor and Director of Post Professional Steven George PT, PhD Education Associate Professor and Assistant Doctoral Programs in Physical Therapy, Department Chair Newark Campus Director, Doctor of Physical Therapy Rutgers University, Newark, NJ Program Director, Brooks-PHHP Research Randy Richter, PT, PhD Collaboration Professor, Program in Physical Therapy University of Florida, Gainesville FL Saint Louis University, Saint Louis, MO Laurita Hack, PT, DPT, MBA, PhD, Robert Wainner, PT, PhD FAPTA Associate Professor, Dept. of Physical Professor Emeritus, Therapy Department of Physical Therapy Texas State University, TX Temple University, Bryn Mawr, PA Evidence Based Practice Special Interest Group, American -

How to Design Vector Control Efficacy Trials

HOW TO DESIGN VECTOR CONTROL EFFICACY TRIALS Guidance on phase III vector control field trial design provided by the Vector Control Advisory Group Acknowledgements The main text was prepared by Anne Wilson and Steve Lindsay (Durham University, England), with major contributions from Immo Kleinschmidt (London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, England), Tom Smith (Swiss Tropical and Pub- lic Health Institute, Switzerland) and Ryan Wiegand (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States of Amer- ica). The document is based on a peer-reviewed manuscript (14). The authors would like to thank the following experts, including those who attended the Expert Advisory Group on Design of Epidemiological Trials for Vector Control Products, held 24–25 April 2017, and the Vector Control Advisory Group for their contributions to the guidance document: Salim Abdulla, Till Baernighausen, Christian Bottomley, John Bradley, Vincent Corbel, Heather Ferguson, Paul Garner, Azra Ghani, David Jeffries, Sarah Moore, Robert Reiner, Molly Robertson, Mark Rowland, Tom Scott, Joao Bosco Siqueira Jr., and Hassan Vatandoost. We would also like to acknowledge the following individuals for significant contributions to reviewing and editing this work: Anna Drexler, Tessa Knox, Jan Kolaczinski, Emmanuel Temu and Raman Velayudhan. WHO/HTM/NTD/VEM/2017.03 © World Health Organization 2017 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. -

Asking Clinical Questions

MODULE 1: ASKING CLINICAL QUESTIONS There are two main types of clinical questions: background questions and foreground questions. Background questions are those which apply to the clinical topic for all patients (e.g. Does Atrovent improve bronchospasm in asthmatics?). Foreground questions, on the other hand, relate to a specific patient (e.g. Does Atrovent given by nebulization prevent hospital admission in wheezing children aged 6-10 years who present to the ED). The difference is in the granularity or specificity of the question: background questions are true of the world in general whereas foreground questions consider specific aspects of a given patient and give answers that can directly improve an outcome meaningful to your patient. Objectives The resident will be able to: ? Formulate a patient-based clinical question using the PICO format ? Discuss how to map the PICO question onto a literature search Key Concept The PICO format lends itself very well to searching the biomedical literature for quantitative studies. It has you take your question and break it down into subcomponents that can then form the basis for a search for evidence. PICO P – Population I – Intervention C – Comparison O – Outcome Measured Quicklinks Centre for Evidence-based Medicine (University of Toronto): http://www.cebm.utoronto.ca/practise/formulate/ An excellent step by step guide to formulating questions. Centre for Health Evidence: “Users’ Guides to Evidence Based Practice” www.cche.net/usersguides/main.asp This is the chapter from the AMA User’s Guides that we recommend as the handbook for EBP in the residency. It’s available online free at this website. -

Health Technology Assessment on Cervical Cancer Screening, 2000–2014

International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 31:3 (2015), 171–180. c Cambridge University Press 2015. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/S0266462315000197 HEALTH TECHNOLOGY ASSESSMENT ON CERVICAL CANCER SCREENING, 2000–2014 Betsy J. Lahue, Eva Baginska, Sophia S. Li Monika Parisi BD Health Economics and Outcomes Research BD Health Economics and Outcomes Research [email protected] Objectives: The aim of this study was to conduct a review of health technology assessments (HTAs) in cervical cancer screening to highlight the most common metrics HTA agencies use to evaluate and recommend cervical cancer screening technologies. Methods: The Center for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD), MedLine, and national HTA agency databases were searched using keywords (“cervical cancer screening” OR “cervical cancer” OR “cervical screening”) and “HTA” from January 2000 to October 2014. Non-English language reports without English summaries, non-HTA reports, HTAs unrelated to a screening intervention and HTAs without sufficient summaries available online were excluded. We used various National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) methods to extract key assessment criteria and to determine whether a change in screening practice was recommended. Results: One hundred and ten unique HTA reports were identified; forty-four HTAs from seventeen countries met inclusion criteria. All reports evaluated technologies for use among women. Ten cervical screening technologies were identified either as an intervention or a comparator. -

How to Design a Randomised Controlled Trial Brocklehurst, Paul

How to design a Randomised Controlled Trial ANGOR UNIVERSITY Brocklehurst, Paul; Hoare, Zoe British Dental Journal DOI: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.411 PRIFYSGOL BANGOR / B Published: 01/05/2017 Peer reviewed version Cyswllt i'r cyhoeddiad / Link to publication Dyfyniad o'r fersiwn a gyhoeddwyd / Citation for published version (APA): Brocklehurst, P., & Hoare, Z. (2017). How to design a Randomised Controlled Trial. British Dental Journal, 222, 721-726. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.411 Hawliau Cyffredinol / General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. 01. Oct. 2021 How to design a Randomised Controlled Trial? Professor Paul Brocklehurst BDS, FFGDP, MDPH, PhD, FDS RCS Director of NWORTH Clinical Trials Unit and Honorary Consultant in Dental Public Health Dr Zoe Hoare BSc, PhD Principal Statistician, NWORTH Clinical Trials Unit Contact: Professor Paul Brocklehurst Director of NWORTH Clinical Trials Unit http://nworth-ctu.bangor.ac.uk @NWORTH_CTU Introduction Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are the work-horse of evidence-based health- care and the only research design that can demonstrate causality i.e. -

Case Studies in Therapeutic Recreation

Case Studies in Therapeutic Recreation Sherri Hildebrand and Rachel E. Smith https://www.sagamorepub.com/products/case-studies-therapeutic-recreation?src=fdpil Case Studies in Therapeutic Recreation Sherri Hildebrand Rachel E. Smith https://www.sagamorepub.com/products/case-studies-therapeutic-recreation?src=fdpil ©2017 Sagamore–Venture Publishing LLC All rights reserved. Publishers: Joseph J. Bannon and Peter L. Bannon Sales and Marketing Manager: Misti Gilles Sales and Marketing Assistant: Kimberly Vecchio Director of Development and Production: Susan M. Davis Production Coordinator: Amy S. Dagit Graphic Designer: Marissa Willison Library of Congress Control Number: 2017952400 ISBN print edition: 978-1-57167-889-8 ISBN ebook: 978-1-57167-890-4 Printed in the United States. 1807 N. Federal Dr. Urbana, IL 61801 www.sagamorepublishing.com https://www.sagamorepub.com/products/case-studies-therapeutic-recreation?src=fdpil To our students past, present, and future, always remember, “The expert in anything was once a beginner.” –Helen Hayes https://www.sagamorepub.com/products/case-studies-therapeutic-recreation?src=fdpil https://www.sagamorepub.com/products/case-studies-therapeutic-recreation?src=fdpil Contents Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................... vii About the Authors ................................................................................................................ix Section I: Introduction Problem-Based Learning ...................................................................................5