How to Design a Randomised Controlled Trial Brocklehurst, Paul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rigorous Clinical Trial Design in Public Health Emergencies Is Essential

1 Rigorous Clinical Trial Design in Public Health Emergencies Is Essential Susan S. Ellenberg (Department of Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Informatics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania); Gerald T. Keusch (Departments of Medicine and Global Health, Boston University Schools of Medicine and Public Health); Abdel G. Babiker (Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Unit, University College London); Kathryn M. Edwards (Department of Pediatrics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine); Roger J. Lewis (Department of Emergency Medicine, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center); Jens D. Lundgren( Department of Infectious Diseases, University of Copenhagen); Charles D. Wells (Infectious Diseases Unit, Sanofi-U.S.); Fred Wabwire-Mangen (Department of Epidemiology, Makerere University School of Public Health); Keith P.W.J. McAdam (Department of Clinical and Tropical Medicine, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine) Keywords: randomized clinical trial; Ebola; ethics Running title: Research in public health emergencies Key Points: To obtain definitive information about the effects of treatments and vaccines, even in public health emergencies, randomized clinical trials are essential. Such trials are ethical and feasible with efforts to engage and collaborate with the affected communities. Contact information, corresponding author: Susan S. Ellenberg, Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania 423 Guardian Drive, Room 611 Philadelphia, PA 19104 [email protected]; 215-573-3904 Contact information, alternate corresponding author: Gerald T. Keusch, MD Boston University School of Medicine 620 Albany St Boston, MA 02118 [email protected]; 617-414-8960 2 ABSTRACT Randomized clinical trials are the most reliable approaches to evaluating the effects of new treatments and vaccines. During the 2014-15 West African Ebola epidemic, many argued that such trials were neither ethical nor feasible in an environment of limited health infrastructure and severe disease with a high fatality rate. -

Transcriptional Biomarkers for Predicting Development of TB: Progress and Clinical Considerations

Early View ERJ Methods Transcriptional biomarkers for predicting development of TB: progress and clinical considerations Hanif Esmail, Frank Cobelens, Delia Goletti Please cite this article as: Esmail H, Cobelens F, Goletti D. Transcriptional biomarkers for predicting development of TB: progress and clinical considerations. Eur Respir J 2020; in press (https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01957-2019). This manuscript has recently been accepted for publication in the European Respiratory Journal. It is published here in its accepted form prior to copyediting and typesetting by our production team. After these production processes are complete and the authors have approved the resulting proofs, the article will move to the latest issue of the ERJ online. Copyright ©ERS 2020 Transcriptional biomarkers for predicting development of TB: progress and clinical considerations Hanif Esmail1,2,3, Frank Cobelens4, Delia Goletti5* 1. Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Unit at University College London, London, UK 2. Institute for Global Health, University College London, London, UK 3. Wellcome Centre for Infectious Diseases Research in Africa, Institute of Infectious Diseases and Molecular Medicine, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa 4. Dept of Global Health and Amsterdam Institute for Global Health and Development, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 5. Translational Research Unit, Department of Epidemiology and Preclinical Research, “L. Spallanzani” National Institute for Infectious Diseases (INMI), IRCCS, Via Portuense 292, 00149 Rome, Italy * Corresponding author Key words: Transcriptional biomarkers, incipient tuberculosis, latent tuberculosis Introduction Achieving the ambitious targets for global tuberculosis (TB) control, will require an increased emphasis on preventing development of active disease in those with latent TB infection (LTBI) by preventative treatment or vaccination[1]. -

Evidence Based Answers to Clinical Questions for Busy Clinicians

Evidence-Based Answers to Clinical Questions for Busy Clinicians Workbook Harris C & Turner T 2011 Updated 2018 This publication should be cited as: Harris C & Turner T. Evidence-Based Answers to Clinical Questions for Busy Clinicians. (2011) The Centre for Clinical Effectiveness, Monash Health, Melbourne, Australia. Copyright © This publication is the copyright of Monash Health. Other than for the purposes and subject to the conditions prescribed under the Copyright Act 1968 as amended, no part of this publication may, in any form or by any means (electric, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise), be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to Centre for Clinical Effectiveness. Acknowledgements The authors would like to acknowledge past and present staff of the Centre for Clinical Effectiveness at Monash Health for their contributions towards the development of this resource. Centre for Clinical Effectiveness Monash Health Phone: +61 3 9594 7575 Fax: +61 3 9594 6018 Email: [email protected] Web : www.monashhealth.org/cce Evidence-Based Answers to Clinical Questions for Busy Clinicians Workbook 2 Objectives This workbook aims to help you to find the best available evidence to answer your clinical questions, in the shortest possible time. It will introduce the principles of evidence-based practice and provide a foundation of understanding and skills in: o Developing questions that are answerable from the literature o Searching for and identifying evidence to answer your question o Appraising the evidence identified for quality, reliability, accuracy and relevance Contents page 1. What is evidence-based practice? 4 2. -

Metformin Does Not Affect Cancer Risk: a Cohort Study in the U.K

2522 Diabetes Care Volume 37, September 2014 Metformin Does Not Affect Cancer Konstantinos K. Tsilidis,1,2 Despoina Capothanassi,1 Naomi E. Allen,3 Risk: A Cohort Study in the U.K. Evangelos C. Rizos,4 David S. Lopez,5 Karin van Veldhoven,6–8 Clinical Practice Research Carlotta Sacerdote,7 Deborah Ashby,9 Paolo Vineis,6,7 Ioanna Tzoulaki,1,6 and Datalink Analyzed Like an John P.A. Ioannidis10 Intention-to-Treat Trial Diabetes Care 2014;37:2522–2532 | DOI: 10.2337/dc14-0584 OBJECTIVE Meta-analyses of epidemiologic studies have suggested that metformin may re- 1Department of Hygiene and Epidemiology, Uni- duce cancer incidence, but randomized controlled trials did not support this versity of Ioannina School of Medicine, Ioannina, hypothesis. Greece 2Cancer Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford, EPIDEMIOLOGY/HEALTH SERVICES RESEARCH RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS Oxford, U.K. 3 A retrospective cohort study, Clinical Practice Research Datalink, was designed to Clinical Trial Service Unit, University of Oxford, Oxford, U.K. investigate the association between use of metformin compared with other anti- 4Lipid Disorders Clinic, Department of Internal diabetes medications and cancer risk by emulating an intention-to-treat analysis Medicine, University Hospital of Ioannina, Ioan- as in a trial. A total of 95,820 participants with type 2 diabetes who started taking nina, Greece 5 metformin and other oral antidiabetes medications within 12 months of their Division of Epidemiology, University of Texas School of Public Health, Houston, TX diagnosis (initiators) were followed up for first incident cancer diagnosis without 6Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, regard to any subsequent changes in pharmacotherapy. -

The PRISMA-IPD Statement

Clinical Review & Education Special Communication Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Individual Participant Data The PRISMA-IPD Statement Lesley A. Stewart, PhD; Mike Clarke, DPhil; Maroeska Rovers, PhD; Richard D. Riley, PhD; Mark Simmonds, PhD; Gavin Stewart, PhD; Jayne F. Tierney, PhD; for the PRISMA-IPD Development Group Editorial page 1625 IMPORTANCE Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of individual participant data (IPD) aim Supplemental content at to collect, check, and reanalyze individual-level data from all studies addressing a particular jama.com research question and are therefore considered a gold standard approach to evidence synthesis. They are likely to be used with increasing frequency as current initiatives to share clinical trial data gain momentum and may be particularly important in reviewing controversial therapeutic areas. OBJECTIVE To develop PRISMA-IPD as a stand-alone extension to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Statement, tailored to the specific requirements of reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of IPD. Although developed primarily for reviews of randomized trials, many items will apply in other contexts, including reviews of diagnosis and prognosis. DESIGN Development of PRISMA-IPD followed the EQUATOR Network framework guidance and used the existing standard PRISMA Statement as a starting point to draft additional relevant material. A web-based survey informed discussion at an international workshop that included researchers, clinicians, methodologists experienced in conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of IPD, and journal editors. The statement was drafted and iterative refinements were made by the project, advisory, and development groups. The PRISMA-IPD Development Group reached agreement on the PRISMA-IPD checklist and flow diagram by consensus. -

Application of the PICO Process to Plan Treatment for a Child with a Co-Occurring Stuttering and Phonological Disorder

Volume 8, Issue 6 March 2014 EBP briefs A scholarly forum for guiding evidence-based practices in speech-language pathology Application of the PICO Process to Plan Treatment for a Child With a Co-occurring Stuttering and Phonological Disorder Keegan M. Koehlinger Linda Louko Patricia Zebrowski EBP Briefs Editor Laura Justice The Ohio State University Associate Editor Mary Beth Schmitt The Ohio State University Editorial Review Board Tim Brackenbury Lisa Milman Bowling Green State University Utah State University Jayne Brandel Cynthia O’Donoghue Fort Hays State University James Madison University Kathy Clapsaddle Amy Pratt Private Practice (Texas) The Ohio State University Lynn Flahive Nicole Sparapani Texas Christian University Florida State University Managing Director Tina Eichstadt Pearson 5601 Green Valley Drive Bloomington, MN 55437 Cite this document as: Koehlinger, K. M., Louko, L., & Zebrowski, P. (2014). Application of the PICO process to plan treatment for a child with a co-occurring stuttering and phonological disorder. EBP Briefs, 8(6), 1–9. Bloomington, MN: Pearson. Copyright © 2014 NCS Pearson, Inc. All rights reserved. Warning: No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without the express written permission of the copyright owner. Pearson, PSI design, and PsychCorp are trademarks, in the US and/or other countries, of Pearson Education, Inc., or its affiliate(s). NCS Pearson, Inc. 5601 Green Valley Drive Bloomington, MN 55437 800.627.7271 www.PearsonClinical.com Produced in the United States of America. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 A B C D E Application of the PICO Process to Plan Treatment for a Child With a Co-occurring Stuttering and Phonological Disorder Keegan M. -

Diagnostic Accuracy of a Host Response Point-Of-Care Test In

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.27.20114512; this version posted June 2, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . Diagnostic accuracy of a host response point-of-care test in patients with suspected COVID-19 Tristan W Clark1,2,3,4*, Nathan J Brendish1, 2, Stephen Poole1,2,3, Vasanth V Naidu2, Christopher Mansbridge2, Nicholas Norton2, Helen Wheeler3, Laura Presland3 and Sean Ewings5 1. School of Clinical and Experimental Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK 2. Department of Infection, University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, Southampton, UK. 3. NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre, University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, Southampton, UK 4. NIHR Post Doctoral Fellowship Programme, UK 5. Southampton Clinical Trials Unit, University of Southampton, UK *Corresponding author Dr Tristan William Clark, Associate Professor and Consultant in Infectious Diseases. NIHR Post Doctoral Fellow. Address: LF101, South Academic block, Southampton General Hospital, Southampton, SO16 6YD. Tel: 0044(0)23818410 E-mail address: [email protected] 1 NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.27.20114512; this version posted June 2, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

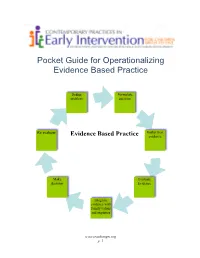

Pocket Guide for Operationalizing Evidence Based Practice

Pocket Guide for Operationalizing Evidence Based Practice Define Formulate problem question Re evaluate Gather best Evidence Based Practice evidence Make Evaluate decision Evidence Integrate evidence with family values and expertise www.teachinngei.org p. 1 Define the Problem When a service provider is attempting to understand a new problem, often their questions are broad making it difficult to gather information to inform decisions. Narrowing the problem to certain element gives the best starting point in a search for evidence. Formulate the Question A well constructed question makes the search for evidence easier and more efficient. A good question should contain the specific group or population, the intervention or issue being addressed/ compared and the desired outcome. Gathering the Best Evidence Many sources of evidence come together to inform decisions made about practice. It is important to have the skills and strategies to make timely and effective decisions. Sources of best evidence include • Information sources: publications, databases, web sites, laws and policies • Service provider experience and expertise • Family values, beliefs, priorities and concerns Information Sources: 1. Publications There are a wide range of publications available with information about practice across disciplines in early childhood. Scholarly publications are the most likely to yield accurate information needed to make decisions. These sources include: o Peer-reviewed journals o Research articles o Guidelines and recommended practices o Systematic reviews and Meta-analysis o Books o Reports o Magazines, non- peer reviewed journals 1a. Peer Reviewed Information Information from peer-reviewed or refereed publications is considered high quality because the process to publish requires the scrutiny of experts in the field as well as scientific methods. -

Download and Use

Shenkin et al. BMC Medicine (2019) 17:138 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1367-9 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Delirium detection in older acute medical inpatients: a multicentre prospective comparative diagnostic test accuracy study of the 4AT and the confusion assessment method Susan D. Shenkin1, Christopher Fox2, Mary Godfrey3, Najma Siddiqi4, Steve Goodacre5, John Young6, Atul Anand7, Alasdair Gray8, Janet Hanley9, Allan MacRaild8, Jill Steven8, Polly L. Black8, Zoë Tieges1, Julia Boyd10, Jacqueline Stephen10, Christopher J. Weir10 and Alasdair M. J. MacLullich1* Abstract Background: Delirium affects > 15% of hospitalised patients but is grossly underdetected, contributing to poor care. The 4 ‘A’s Test (4AT, www.the4AT.com) is a short delirium assessment tool designed for routine use without special training. Theprimaryobjectivewastoassesstheaccuracyofthe4ATfor delirium detection. The secondary objective was to compare the 4AT with another commonly used delirium assessment tool, the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM). Methods: This was a prospective diagnostic test accuracy study set in emergency departments or acute medical wards involving acute medical patients aged ≥ 70. All those without acutely life-threatening illness or coma were eligible. Patients underwent (1) reference standard delirium assessment based on DSM-IV criteria and (2) were randomised to either the index test (4AT, scores 0–12; prespecified score of > 3 considered positive) or the comparator (CAM; scored positive or negative), in a random order, using computer-generated pseudo-random numbers, stratified by study site, with block allocation. Reference standard and 4AT or CAM assessments were performed by pairs of independent raters blinded to the results of the other assessment. Results: Eight hundred forty-three individuals were randomised: 21 withdrew, 3 lost contact, 32 indeterminate diagnosis, 2 missing outcome, and 785 were included in the analysis. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Clinical Judgement in the era of Evidence Based Medicine Flores Sepulveda, Luis Jose Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to: Share: to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Nov. 2017 Clinical judgment in the era of Evidence Based Medicine Submitted to the Department of Philosophy of King’s College London, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of philosophy Luis Flores MD. -

Clinical Trial Design and Clinical Trials Unit

Clinical trial design and Clinical Trials Unit Nina L. Jebsen, MD, PhD Centre for Cancer Biomarkers, University of Bergen Centre for Bone- and Soft Tissue Tumours, Haukeland University Hospital Outline • Why clinical studies? • Preconditions • Principles • Types of clinical trials • Different phases in clinical trials • Design of clinical trials – Basket design – Enrichment design – Umbrella design – Marker-based strategy design – Adaptive design • Clinical Trials Unit • CTU, Haukeland University Hospital Why clinical studies? • Control/optimize an experimental process to – reduce errors/bias = internal validity/credibility – reduce variability = external validity/reproducibility – QA data collection settings = model validity/design • Understand the biological chain of events that lead to disease progression and response to intervention • Simplify and validate statistical data analysis • Generate evidence for effect of a specific treatment . in a specific population • Results extrapolated for standard clinical use . • Necessary (Phase III) for drug approval • Take into account ethical issues Preconditions • Access to patients (be realistic) • Approvals by legal authorities • Accept from local hospital department • Adequate resources/financial support • Infrastructure • Necessary equipment • Experienced personnel • Well-functioning routines • Study-team with mutual understanding of all implications Study population vs clinical practice • Age – study patients often younger • Performance status – study patients better performance status -

This Is the Title of My Thesis

A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Interventions (Pharmaceutical and Psychosocial) for Cognitive and Learning Impairments in Children Diagnosed with a Brain Tumour Lisa-Jane Keegan Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Clinical Psychology (D. Clin. Psychol.) The University of Leeds School of Medicine Academic Unit of Psychiatry and Behavioural Sciences September 2014 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2014 The University of Leeds and Lisa-Jane Keegan (Optional) The right of Lisa-Jane Keegan to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am sincerely grateful for the help of Professor Stephen Morley and Dr Matthew Morrall, without their support, time and patience this thesis would never have been possible. A big thank you to Miss Rosa Reed-Berendt (Research Assistant), Mr Paul Farrington (Psychologist in Forensic Training), Miss Elizabeth Neilly – Health Faculty Team Librarian, Ms Janet Morton – Education Faculty Team Librarian, Drs Picton, Wilkins and Elliott - Consultant Paediatric Oncologists, Dr Livingston - Consultant Paediatric Neurologist at The Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Miss Helen Stocks, Miss Kate Ablett and Dr Stanley, Consultant Child & Adolescent Psychiatrist, Leeds Community Healthcare NHS Trust, Suzanne Donald (Honorary Research Assistant) and Michael Ferriter- Lead for Research, Forensic Division, Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust; who have supported me to achieve my goal.