Saint Thomas Aquinas' Division of the Sciences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. Polycarp Feast: February 23

St. Polycarp Feast: February 23 Facts Feast Day: February 23 Imagine being able to sit at the feet of the apostles and hear their stories of life with Jesus from their own lips. Imagine walking with those who had walked with Jesus, seen him, and touched him. That was what Polycarp was able to do as a disciple of Saint John the Evangelist. But being part of the second generation of Church leaders had challenges that the first generation could not teach about. What did you do when those eyewitnesses were gone? How do you carry on the correct teachings of Jesus? How do you answer new questions that never came up before? With the apostles gone, heresies sprang up pretending to be true teaching, persecution was strong, and controversies arose over how to celebrate liturgy that Jesus never laid down rules for. Polycarp, as a holy man and bishop of Smyrna, found there was only one answer -- to be true to the life of Jesus and imitate that life. Saint Ignatius of Antioch told Polycarp "your mind is grounded in God as on an immovable rock." When faced with heresy, he showed the "candid face" that Ignatius admired and that imitated Jesus' response to the Pharisees. Marcion, the leader of the Marcionites who followed a dualistic heresy, confronted Polycarp and demanded respect by saying, "Recognize us, Polycarp." Polycarp responded, "I recognize you, yes, I recognize the son of Satan." On the other hand when faced with Christian disagreements he was all forgiveness and respect. One of the controversies of the time came over the celebration of Easter. -

Year of Saint Joseph

DIOCESE OF SACRAMENTO Office of Worship 2110 Broadway, Sacramento, CA 95818 - 916-733-0211 - [email protected] Year of Saint Joseph On the Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception in 2020, Pope Francis has released an apostolic letter about Saint Joseph and declared a “Year of St. Joseph” from December 8, 2020 to December 8, 2021. The letter, Patris Corde (“a Father’s heart”) was released on the 150th anniversary of the proclamation of Saint Joseph as patron of the Universal Church. It can be found here: http://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/apost_letters/documents/papa-francesco-lettera- ap_20201208_patris-corde.html The Diocese of Sacramento is observing this Year in many ways. Journey with Joseph Pilgrimage We will soon be announcing Saint Joseph pilgrimage sites across the Diocese. Indulgence The Apostolic Penitentiary issued a decree on December 8, 2020, formally announcing the decision of Pope Francis to celebrate the Year of Saint Joseph through December 8, 2021. Special opportunities to receive a plenary indulgence were also included, subject to the usual conditions: sacramental confession, reception of Holy Communion, prayer for the intentions of the Pope, and total detachment to all sin, including venial sin. Due to the ongoing coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, the Holy See made provision in its decree that persons who are currently unable to go to Mass or confession because of public health restrictions may defer reception of those two sacraments until they are able to do so. Those who are sick, suffering, or homebound may also receive the plenary indulgence by fulfilling as much as they are able and by offering their sorrows and sufferings to God through Saint Joseph, consoler of the sick and patron saint for receiving a good death. -

Life with Augustine

Life with Augustine ...a course in his spirit and guidance for daily living By Edmond A. Maher ii Life with Augustine © 2002 Augustinian Press Australia Sydney, Australia. Acknowledgements: The author wishes to acknowledge and thank the following people: ► the Augustinian Province of Our Mother of Good Counsel, Australia, for support- ing this project, with special mention of Pat Fahey osa, Kevin Burman osa, Pat Codd osa and Peter Jones osa ► Laurence Mooney osa for assistance in editing ► Michael Morahan osa for formatting this 2nd Edition ► John Coles, Peter Gagan, Dr. Frank McGrath fms (Brisbane CEO), Benet Fonck ofm, Peter Keogh sfo for sharing their vast experience in adult education ► John Rotelle osa, for granting us permission to use his English translation of Tarcisius van Bavel’s work Augustine (full bibliography within) and for his scholarly advice Megan Atkins for her formatting suggestions in the 1st Edition, that have carried over into this the 2nd ► those generous people who have completed the 1st Edition and suggested valuable improvements, especially Kath Neehouse and friends at Villanova College, Brisbane Foreword 1 Dear Participant Saint Augustine of Hippo is a figure in our history who has appealed to the curiosity and imagination of many generations. He is well known for being both sinner and saint, for being a bishop yet also a fellow pilgrim on the journey to God. One of the most popular and attractive persons across many centuries, his influence on the church has continued to our current day. He is also renowned for his influ- ence in philosophy and psychology and even (in an indirect way) art, music and architecture. -

Basics of Social Network Analysis Distribute Or

1 Basics of Social Network Analysis distribute or post, copy, not Do Copyright ©2017 by SAGE Publications, Inc. This work may not be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without express written permission of the publisher. Chapter 1 Basics of Social Network Analysis 3 Learning Objectives zz Describe basic concepts in social network analysis (SNA) such as nodes, actors, and ties or relations zz Identify different types of social networks, such as directed or undirected, binary or valued, and bipartite or one-mode zz Assess research designs in social network research, and distinguish sampling units, relational forms and contents, and levels of analysis zz Identify network actors at different levels of analysis (e.g., individuals or aggregate units) when reading social network literature zz Describe bipartite networks, know when to use them, and what their advan- tages are zz Explain the three theoretical assumptions that undergird social networkdistribute studies zz Discuss problems of causality in social network analysis, and suggest methods to establish causality in network studies or 1.1 Introduction The term “social network” entered everyday language with the advent of the Internet. As a result, most people will connect the term with the Internet and social media platforms, but it has in fact a much broaderpost, application, as we will see shortly. Still, pictures like Figure 1.1 are what most people will think of when they hear the word “social network”: thousands of points connected to each other. In this particular case, the points represent political blogs in the United States (grey ones are Republican, and dark grey ones are Democrat), the ties indicating hyperlinks between them. -

English Knowledge Base Category Hierarchy

J English Knowledge Base Category Hierarchy This document provides a list of all the concepts in the knowledge base that serve as categories. This document divided into six sections, corresponding to the six main branches of the knowledge base: ■ Branch 1: science and technology ■ Branch 2: business and economics ■ Branch 3: government and military ■ Branch 4: social environment ■ Branch 5: geography ■ Branch 6: abstract ideas and concepts The categories are presented in an inverted-tree hierarchy and within each category, sub-categories are listed in alphabetical order. Note: This document does not contain all the concepts found in the knowledge base. It only contains those concepts that serve as categories (meaning they are parent nodes in the hierarchy). English Knowledge Base Category Hierarchy J-1 Branch 1: science and technology Branch 1: science and technology [1] communications [2] journalism [3] broadcast journalism [3] photojournalism [3] print journalism [4] newspapers [2] public speaking [2] publishing industry [3] desktop publishing [3] periodicals [4] business publications [3] printing [2] telecommunications industry [3] computer networking [4] Internet technology [5] Internet providers [5] Web browsers [5] search engines [3] data transmission [3] fiber optics [3] telephone service [1] formal education [2] colleges and universities [3] academic degrees [3] business education [2] curricula and methods [2] library science [2] reference books [2] schools [2] teachers and students [1] hard sciences [2] aerospace industry [3] -

The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St

NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St. Jerome About NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St. Jerome Title: NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf206.html Author(s): Jerome, St. Schaff, Philip (1819-1893) (Editor) Freemantle, M.A., The Hon. W.H. (Translator) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Print Basis: New York: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1892 Source: Logos Inc. Rights: Public Domain Status: This volume has been carefully proofread and corrected. CCEL Subjects: All; Proofed; Early Church; LC Call no: BR60 LC Subjects: Christianity Early Christian Literature. Fathers of the Church, etc. NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome St. Jerome Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii Title Page.. p. 1 Title Page.. p. 2 Translator©s Preface.. p. 3 Prolegomena to Jerome.. p. 4 Introductory.. p. 4 Contemporary History.. p. 4 Life of Jerome.. p. 10 The Writings of Jerome.. p. 22 Estimate of the Scope and Value of Jerome©s Writings.. p. 26 Character and Influence of Jerome.. p. 32 Chronological Tables of the Life and Times of St. Jerome A.D. 345-420.. p. 33 The Letters of St. Jerome.. p. 40 To Innocent.. p. 40 To Theodosius and the Rest of the Anchorites.. p. 44 To Rufinus the Monk.. p. 44 To Florentius.. p. 48 To Florentius.. p. 49 To Julian, a Deacon of Antioch.. p. 50 To Chromatius, Jovinus, and Eusebius.. p. 51 To Niceas, Sub-Deacon of Aquileia. -

Mechanistic Hierarchy Realism and Function Perspectivalism

1 Mechanistic Hierarchy Realism and Function Perspectivalism Abstract Mechanistic explanation involves the attribution of functions to both mechanisms and their component parts, and function attribution plays a central role in the individuation of mechanisms. Our aim in this paper is to investigate the impact of a perspectival view of function attribution for the broader mechanist project, and specifically for realism about mechanistic hierarchies. We argue that, contrary to the claims of function perspectivalists such as Craver, one cannot endorse both function perspectivalism and mechanistic hierarchy realism: if functions are perspectival, then so are the levels of a mechanistic hierarchy. We illustrate this argument with an example from recent neuroscience, where the mechanism responsible for the phenomenon of ephaptic coupling cross-cuts (in a hierarchical sense) the more familiar mechanism for synaptic firing. Finally, we consider what kind of structure there is left to be realist about for the function perspectivalist. 1. Introduction Mechanistic explanation has emerged as the dominant account of explanation across much of philosophy of science, especially for cognitive neuroscience, biology, and chemistry. This account suggests that to explain a phenomenon is to offer a mechanism that produces it. Crucially, for many mechanists, mechanisms differ from models and other idealized, counterfactual, or instrumental constructs of science, in that mechanisms are actual parts of the world. Models, diagrams, simulations, or other descriptions may represent a mechanism, but the mechanism itself comprises a real structure, independent of our aims and interests, and this real structure plays an explanatory role (either constitutively, for ontic mechanists, or 2 by reference, for epistemic mechanists – we will return to this point later). -

St. Thomas Aquinas Catholic School Vision Statement

St. Thomas Aquinas Catholic School School Handbook Effective August, 2016 1 STA 8/2016 St. Thomas Aquinas Catholic School Vision Statement With the combined efforts of the church, school families, and faculty, Saint Thomas Aquinas School will guide a diverse student body toward becoming responsible, faith-filled, caring citizens and independent learners. St. Thomas Aquinas Catholic School Mission Statement At Saint Thomas Aquinas School, our mission is to create opportunities for students to grow spiritually, academically, socially and physically in a safe environment. Students will grow spiritually. At Saint Thomas Aquinas School, the church, school families and faculty will provide an understanding of the basic tenets of our Catholic Faith which encourages students to participate in the sacraments, embrace Christian values, and serve others,. Students will grow academically. At Saint Thomas Aquinas School, faculty will provide a rich curriculum utilizing technology, and other differentiated teaching techniques which accommodates all styles of learning, encourages critical thinking, and fosters a love of learning. Students will grow socially. At Saint Thomas Aquinas School, the church, school families and faculty will provide opportunities for students to interact with a diverse community of people in an environment which encourages tolerance, empathy, respect, and a sense of belonging. Students will grow physically. At Saint Thomas Aquinas School, the church, school families and faculty will provide guidance to students in making lifestyle -

Exclusivity, Teleology and Hierarchy: Our Aristotelean Legacy

Know!. Org. 26(1999)No.2 65 H.A. Olson: Exclusivity, Teleology and Hierarchy: Our Aristotelean Legacy Exclusivity, Teleology and Hierarchy: Our Aristotelean Legacy Hope A. Olson School of Library & Information Studies, University of Alberta Hope A. Olson is an Associate Professor and Graduate Coordinator in the School of Library and Information Studies at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. She holds a PhD from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and MLS from the University of Toronto. Her re search is generally in the area of subject access to information with a focus on classification. She approaches this work using feminist, poststructural and postcolonial theory. Dr. Olson teaches organization of knowledge, cataloguing and classification, and courses examining issues in femi nism and in globalization and diversity as they relate to library and information studies. Olson, H.A. (1999). Exclusivity, Teleology and Hierarchy: Our Aristotelean Legacy. Knowl· edge Organization, 26(2). 65-73. 16 refs. ABSTRACT: This paper examines Parmenides's Fragments, Plato's The Sophist, and Aristotle's Prior AnalyticsJ Parts ofAnimals and Generation ofAnimals to identify three underlying presumptions of classical logic using the method of Foucauldian discourse analysis. These three presumptions are the notion of mutually exclusive categories, teleology in the sense of linear progression toward a goal, and hierarchy both through logical division and through the dominance of some classes over others. These three presumptions are linked to classificatory thought in the western tradition. The purpose of making these connections is to investi gate the cultural specificity to western culture of widespread classificatory practice. It is a step in a larger study to examine classi fication as a cultural construction that may be systemically incompatible with other cultures and with marginalized elements of western culture. -

The Problem of Social Class Under Socialism Author(S): Sharon Zukin Source: Theory and Society, Vol

The Problem of Social Class under Socialism Author(s): Sharon Zukin Source: Theory and Society, Vol. 6, No. 3 (Nov., 1978), pp. 391-427 Published by: Springer Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/656759 Accessed: 24-06-2015 21:55 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/656759?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Theory and Society. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 132.236.27.111 on Wed, 24 Jun 2015 21:55:45 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 391 THE PROBLEM OF SOCIAL CLASS UNDER SOCIALISM SHARON ZUKIN Posing the problem of social class under socialismimplies that the concept of class can be removed from the historical context of capitalist society and applied to societies which either do not know or do not claim to know the classicalcapitalist mode of production. Overthe past fifty years, the obstacles to such an analysis have often led to political recriminationsand termino- logical culs-de-sac. -

From a Treatise on John by Saint Augustine, Bishop Saint Augustine

From a treatise on John by Saint Augustine, bishop Saint Augustine of Hippo Augustine of Hippo: (13 November 354 – 28 August 430 AD), was a Roman African, Manichaean, early Christian theologian, doctor of the Church, and Neoplatonic philosopher from Numidia whose writings influenced the development of the Western Church and Western philosophy, and indirectly all of Western Christianity. After exploring many religions and philosophies he became a Catholic in his thirties. He was the bishop of Hippo Regius in North Africa and is viewed as one of the most important Church Fathers of the Roman Catholic Church for his writings in the Patristic Period. Among his most important works are The City of God, De doctrina Christiana, and Confessions. Two kinds of life The Church recognizes two kinds of life as having been commended to her by God. One is a life of faith, the other a life of vision; one is a life passed on pilgrimage in time, the other in a dwelling place in eternity; one is a life of toil, the other of repose; one is spent on the road, the other in our homeland; one is active, involving labor, the other contemplative, the reward of labor. The first kind of life is symbolized by the apostle Peter, the second by John. All of the first life is lived in this world, and it will come to an end with this world. The second life will be imperfect till the end of this world, but it will have no end in the next world. And so Christ says to Peter: Follow me; but of John he says: If I wish him to remain until I come, what is that to you? Your duty is to follow me. -

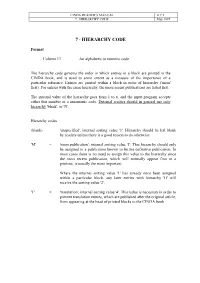

7.1 7 : HIERARCHY CODE May 1997

CINDA READER’S MANUAL II.7.1 7 : HIERARCHY CODE May 1997 7 - HIERARCHY CODE Format Column 17 An alphabetic or numeric code. The hierarchy code governs the order in which entries in a block are printed in the CINDA book, and is used to some extent as a measure of the importance of a particular reference. Entries are printed within a block in order of hierarchy ('main' first). For entries with the same hierarchy, the more recent publications are listed first. The internal value of the hierarchy goes from 1 to 6, and the input program accepts either this number or a mnemonic code. External readers should in general use only hierarchy 'blank', or 'N'. Hierarchy codes (blank) 'unspecified', internal sorting value '3'. Hierarchy should be left blank by readers unless there is a good reason to do otherwise 'M' = 'main publication', internal sorting value '1'. This hierarchy should only be assigned to a publication known to be the definitive publication. In most cases there is no need to assign this value to the hierarchy since the most recent publication, which will normally appear first in a printout, is usually the most important. Where the internal sorting value '1' has already once been assigned within a particular block, any later entries with hierarchy 'H' will receive the sorting value '2'. 'T' = 'translation', internal sorting value '4'. This value is necessary in order to prevent translation entries, which are published after the original article, from appearing at the head of printed blocks in the CINDA book. CINDA READER’S MANUAL II.7.2 7 : HIERARCHY CODE May 1997 Hierarchy codes (cont/d) 'N' = 'No Book Flag'.