TCRP Report 102 – Transit-Oriented

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commuter Rail System Study

TRANSPORTATION PROGRAMS Commuter Rail System Study Transit Committee March 11, 2010 TRANSPORTATION PROGRAMS Study Purpose Study Requested by MAG Regional Council in 2008 Commuter Rail Study Funding in 2004 RTP Study Feasibility of Commuter Rail Service in MAG Region Ridership Forecasting and Cost Effectiveness Capital and Operating Cost Estimates Vehicle Technology Recommendation Implementation Requirements Copyright © 2009 TRANSPORTATION PROGRAMS Peer Regions ~ Commuter Rail Systems WHAT IS COMMUTER RAIL? Peak Period, Peak Direction Service. Traditionally caries less daily riders than light rail, but for longer distances. Similar market and characteristics with Bus Rapid Transit / Express. SOUNDER-Seattle CALTRAIN-San Francisco ALTAMONT COMMUTER EXPRESS – San Jose Can share ROW and track with freight railroads and can operate concurrently (does not require exclusive right-of-way) . Typically longer station spacing (every 3-7 miles on average) than light rail (1-2 miles) with emphasis on park-and-rides and traditional city CBDs. Locomotive technology (diesel or clean/green hybrid Genset). Passenger coaches (push-pull). Engines and cars meets federally mandated structural requirements for rolling stock crash resistance Larger, heavier profile than light rail vehicles. METROLINK – Los Angeles COASTER – San Diego FRONT RUNNER – Salt Lake City-Ogden Higher max.speed (79mph), slower acceleration and deceleration than light rail. Average speed approx 44mph. Lower capital cost per mile ($10-$20M) due to existing right of way use / reuse. Light -

SOUND TRANSIT STAFF REPORT MOTION NO. M2004-23 Quality

SOUND TRANSIT STAFF REPORT MOTION NO. M2004-23 Quality Assurance Materials Testing Services Contract Award Meeting: Date: Type of Action: Staff Contact: Phone: Finance Committee 3/18/04 Discussion/Possible Action Ahmad Fazel, Link Light Rail (206) 398-5389 Director Bill Gardner, Quality (206) 398-5142 Assurance Project Manager Contract/Agreement Type: Requested Action: Competitive Procurement Execute New Contract/Agreement Sole Source Amend Existing Contract/Agreement Interlocal Agreement Contingency Funds (Budget) Required Purchase/Sale Agreement Budget Amendment Required Applicable to proposed transaction. OBJECTIVE OF ACTION Approve a quality assurance (QA) materials testing contract with Kleinfelder, Inc. ACTION Authorizes the Chief Executive Officer to execute a contract with Kleinfelder, Inc. to provide quality assurance materials testing services for the Central Link Light Rail Initial Segment Project in the amount of $1,212,228 plus a wage increase allowance of $159,257 and a contingency of $137,152, for a total authorized contract amount not to exceed $1,508,637. KEY FEATURES • Negotiated contract cost with Kleinfelder, Inc. is $1,212,228. Wage increase allowance of $159,297 is calculated as 2.5% per contract year applied to base contract salaries, plus fringe benefits. • Scope of work includes: - Contracting an independent testing laboratory to provide quality assurance on-call inspection/testing services to Sound Transit Link Construction Management. - Testing services to be provided during the construction phase of the Sound Transit Light Rail contracts on the 14-mile Central Link Light Rail Initial Segment Project, between Convention Place Station in the existing Downtown Seattle Transit Tunnel and the new 154th Street Station in Tukwila. -

Seattle, Washington

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON BRIEF: METRO BUS TRAVEL Table of Contents SEATTLE, WASHINGTON (USA)............................................ 1 SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 1 CITY CONTEXT.............................................................................................................. 1 PLANNING AND IMPLEMENTATION BACKGROUND...................................................... 1 PROJECT DESCRIPTION................................................................................................ 2 STATIONS................................................................................................................. 2 VEHICLES................................................................................................................. 2 SAFETY AND SECURITY............................................................................................ 3 OPERATIONS ............................................................................................................ 3 COSTS ...................................................................................................................... 3 USAGE AND BENEFITS.............................................................................................. 3 ASSESSMENT ................................................................................................................. 4 SEATTLE, WASHINGTON (USA) METRO Bus Travel SUMMARY The 2.1-mile [1.3-kilometer] downtown bus tunnel, which -

California State Rail Plan 2005-06 to 2015-16

California State Rail Plan 2005-06 to 2015-16 December 2005 California Department of Transportation ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER, Governor SUNNE WRIGHT McPEAK, Secretary Business, Transportation and Housing Agency WILL KEMPTON, Director California Department of Transportation JOSEPH TAVAGLIONE, Chair STATE OF CALIFORNIA ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER JEREMIAH F. HALLISEY, Vice Chair GOVERNOR BOB BALGENORTH MARIAN BERGESON JOHN CHALKER JAMES C. GHIELMETTI ALLEN M. LAWRENCE R. K. LINDSEY ESTEBAN E. TORRES SENATOR TOM TORLAKSON, Ex Officio ASSEMBLYMEMBER JENNY OROPEZA, Ex Officio JOHN BARNA, Executive Director CALIFORNIA TRANSPORTATION COMMISSION 1120 N STREET, MS-52 P. 0 . BOX 942873 SACRAMENTO, 94273-0001 FAX(916)653-2134 (916) 654-4245 http://www.catc.ca.gov December 29, 2005 Honorable Alan Lowenthal, Chairman Senate Transportation and Housing Committee State Capitol, Room 2209 Sacramento, CA 95814 Honorable Jenny Oropeza, Chair Assembly Transportation Committee 1020 N Street, Room 112 Sacramento, CA 95814 Dear: Senator Lowenthal Assembly Member Oropeza: On behalf of the California Transportation Commission, I am transmitting to the Legislature the 10-year California State Rail Plan for FY 2005-06 through FY 2015-16 by the Department of Transportation (Caltrans) with the Commission's resolution (#G-05-11) giving advice and consent, as required by Section 14036 of the Government Code. The ten-year plan provides Caltrans' vision for intercity rail service. Caltrans'l0-year plan goals are to provide intercity rail as an alternative mode of transportation, promote congestion relief, improve air quality, better fuel efficiency, and improved land use practices. This year's Plan includes: standards for meeting those goals; sets priorities for increased revenues, increased capacity, reduced running times; and cost effectiveness. -

The I-270 Transit Plan – Planning Board Briefing

MONTGOMERY COUNTY PLANNING DEPARTMENT THE MARYLAND-NATIONAL CAPITAL PARK AND PLANNING COMMISSION MCPB Item No. 8 Date: 07-29-21 Corridor Forward: The I-270 Transit Plan – Planning Board Briefing Jesse Cohn McGowan, Planner Coordinator, Countywide Planning, [email protected], 301.495.2197 Patrick Reed, Planner Coordinator, Mid-County Planning, [email protected], 301.495.4538 Jessica McVary, Master Planner Supervisor, Mid-County Planning, [email protected], 301.495.4723 Jason Sartori, Chief, Countywide Planning, [email protected], 301.495.2172 Carrie Sanders, Chief, Mid-County Planning, [email protected], 301.495.4653 Completed: 07-23-21 SUMMARY Work on Corridor Forward: The I-270 Transit Plan (Corridor Forward) has progressed since the February 2021 briefing in which staff summarized conceptual transit options, presented an overview of the Plan’s pre-screening process, and recommended six transit options to advance for detailed study. Over the last several months, staff has refined the six transit options and completed preliminary analysis of those options, including an evaluation of their strategic merits, an initial assessment of their economic and financial outlook, and a review of each option’s potential implementation challenges and risks. CONTENTS Summary ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose of the Briefing ................................................................................................................................ -

Figure 2: Ballston Station Area Sites EXHIBIT NO.57A2 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia

ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia ZONING COMMISSION Case No. 06-27 District of Columbia CASE NO.06-27 57A2 Figure 2: Ballston Station Area Sites EXHIBIT NO.57A2 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 Figure 3: Courthouse Station Area Sites 57A2 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 Figure 4: Crystal City Station Area Sites 57A2 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 Figure 5: Dunn-Loring-Merrifield Station Area Sites 57A2 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 Figure 6: Eisenhower Avenue and King Street Station Area Sites 57A2 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 Figure 7: Farragut West Station Area Sites 57A2 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 Figure 8: Friendship Heights Station Area Sites 57A2 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 Figure 9: Gallery Place-Chinatown Station Area Sites 57A2 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 57A2 Figure 10: Grosvenor-Strathmore Station Area Sites ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 Figure 11: New Carrollton Station Area Sites 57A2 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 Figure 12: Silver Spring Station Area Sites 57A2 MJ Station Entrance/Exit • Office c::J Residential ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 Figure 13: U Street/African American Civil War Memoriai/Cardozo Station Area Sites 57A2 3. Data Collection At each site, data about the travel characteristics of individuals who work, live, shop or use the sites were collected through a series of questionnaires conducted through self-administered survey forms and oral intercept interviews. -

Quarterly Financial Report FY2017 -- Fourth Quarter April -- June 2017

Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority Fiscal Year 2017 Financials Quarterly Financial Report FY2017 ---Fourth Quarter April ---June 2017 Page 1 of 62 WASHINGTON METROPOLITAN AREA TRANSIT AUTHORITY QUARTERLY FINANCIAL REPORT FY2017 --- Q4 April --- June 2017 _________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents Section Page Key Financial Performance Indicators 3 Operating and Capital Budget Summaries 8 Operating Financials by Mode 26 Parking Facility Usage 30 Capital Expenditures 32 Jurisdictional Balances on Account 41 Grants Activity 43 Contract Activity 45 Page 2 of 62 WASHINGTON METROPOLITAN AREA TRANSIT AUTHORITY QUARTERLY FINANCIAL REPORT FY2017 --- Q4 April --- June 2017 _________________________________________________________________ Key Financial Performance Indicators Page 3 of 62 Page 4 of 62 REVENUE AND RIDERSHIP 4th Quarter FY2017 REVENUE (in Millions) FY2016 Actual FY2017 Budget FY2017 Actual $85M 81 81 $80M 80 79 79 78 78 78 78 76 $75M 75 72 72 72 72 70 70 $70M 70 69 69 68 68 67 67 67 66 66 65 65 65 65 $65M 64 63 63 60 $60M 60 59 59 $55M $50M Jul Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Cumulative Revenue Variance $0M (17.0) -$50M (27.0) (36.6) (45.6) (55.9) (64.6) (69.8) -$100M (76.9) (86.9) (103.0) (109.5) -$150M (116.3) RIDERSHIP (trips in Thousands) Q4 Q4-FY2016 Q4-FY2017 Variance FY17 Actual Actual Budget Prior Year Budget Metrorail 48,768 47,336 54,466 -3% -13% Metrobus 32,142 30,514 35,118 -5% -13% MetroAccess 595 607 618 2% -2% System Total 81,504 78,457 90,202 -4% -13% -

38B Map and Timetable

How to use this timetable Effective 12-18-16 ➤ Use the map to find the stops closest to where you will get on and off the bus. ➤ Select the schedule (Weekday, Saturday, Sunday) for when you will travel. Along the top of the schedule, Ballston-Farragut Square Line find the stop at or nearest the point where you will get on the bus. Follow that column down to the time you want to leave. ➤ Use the same method to find the times the bus is scheduled to arrive at the stop where you will get off the bus. Serves these locations- ➤ If the bus stop is not listed, use the Brinda servicio a estas ubicaciones time shown for the bus stop before it as the time to wait at the stop. l Ballston-MU station ➤ The end-of-the-line or last stop is listed l Clarendon station in ALL CAPS on the schedule. l Court House station Rosslyn station Cómo Usar este Horario l ➤ Use este mapa para localizar las l Georgetown paradas más cercanas a donde se l Farragut North station subirá y bajará del autobús. l Farragut West station ➤ Seleccione el horario (Entre semana, sábado, domingo) de cuando viajará. A lo largo de la parte superior del horario, localice la parada o el punto más cercano a la parada en la que se subirá al autobús. Siga esa columna hacia abajo hasta la hora en la que desee salir. ➤ Utilice el mismo método para localizar las horas en que el autobús está programado para llegar a la parada en donde desea bajarse del autobús. -

A. Purple Line Light Rail, Mandatory Referral No

MONTGOMERY COUNTY PLANNING DEPARTMENT THE MARYLAND-NATIONAL CAPITAL PARK AND PLANNING COMMISSION MCPB Item No. 2 Date: 03/20/14 A. Purple Line Light Rail, Mandatory Referral No. MR2014033 B. Bethesda Metro Station South Entrance, Mandatory Referral No. MR2014034, CIP Project 500929 C. Capital Crescent Trail, Mandatory Referral No. MR2014035, CIP Project 501316 D. Silver Spring Green Trail, Mandatory Referral No. MR2014036, CIP Project 509975 David Anspacher, Planner/Coordinator, [email protected], (301) 495-2191 Mary Dolan, Chief, [email protected], (301) 495-4552 Tom Autrey, Supervisor, [email protected], (301) 495-4533 Robert Kronenberg, Chief, [email protected], (301) 495-2187 Marc DeOcampo, Supervisor, [email protected], (301) 495-4556 Elza Hisel-McCoy, Planner/Coordinator, [email protected], (301) 495-2115 Tina Schneider, Senior Planner, [email protected], (301) 495-2101 Mike Riley, Deputy Director (Parks), [email protected], (301) 495-2500 John Hench, Division Chief, [email protected], (301) 650-4364 Brooke Farquhar, Section Chief, [email protected], (301) 650-4388 Chuck Kines, Park Planner/Coordinator, [email protected], (301) 495-2184 Mitra Pedoeem, Division Chief, [email protected], (301) 495-2554 Andy Frank, Section Chief, [email protected], (301) 650-2886 Jai Cole, Natural Resources Manager, [email protected], (301) 650-4366 Completed: 03/13/2014 Jai Cole, Natural Resources Manager, [email protected], (301) 650-XXXX Description The subject of this staff report is four mandatory referrals for the Purple Line (the portion in Montgomery County only), the Bethesda Metro Station South Entrance, an extension of the Capital Crescent Trail, and an extension of the Silver Spring Green Trail. -

City of Atlanta 2016-2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) Community Work Program (CWP)

City of Atlanta 2016-2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) Community Work Program (CWP) Prepared By: Department of Planning and Community Development 55 Trinity Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30303 www.atlantaga.gov DRAFT JUNE 2015 Page is left blank intentionally for document formatting City of Atlanta 2016‐2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) and Community Work Program (CWP) June 2015 City of Atlanta Department of Planning and Community Development Office of Planning 55 Trinity Avenue Suite 3350 Atlanta, GA 30303 http://www.atlantaga.gov/indeex.aspx?page=391 Online City Projects Database: http:gis.atlantaga.gov/apps/cityprojects/ Mayor The Honorable M. Kasim Reed City Council Ceasar C. Mitchell, Council President Carla Smith Kwanza Hall Ivory Lee Young, Jr. Council District 1 Council District 2 Council District 3 Cleta Winslow Natalyn Mosby Archibong Alex Wan Council District 4 Council District 5 Council District 6 Howard Shook Yolanda Adreaan Felicia A. Moore Council District 7 Council District 8 Council District 9 C.T. Martin Keisha Bottoms Joyce Sheperd Council District 10 Council District 11 Council District 12 Michael Julian Bond Mary Norwood Andre Dickens Post 1 At Large Post 2 At Large Post 3 At Large Department of Planning and Community Development Terri M. Lee, Deputy Commissioner Charletta Wilson Jacks, Director, Office of Planning Project Staff Jessica Lavandier, Assistant Director, Strategic Planning Rodney Milton, Principal Planner Lenise Lyons, Urban Planner Capital Improvements Program Sub‐Cabinet Members Atlanta BeltLine, -

MIRACLE MILE - Between Le Jeune Rd

TERRANOVA www.terranovacorp.com | 305.695.8700 801 Arthur Godfrey Road, Suite 600 Miami Beach, FL 33140 BY THE NUMBERS LINCOLN ROAD - Between Alton Road and Washington Ave. 525,477 sf 6.2% $203.34 of AVERAGE VACANCY RATE Inventory ASKING NET RENT COLLINS AVENUE - Between 5th Street and 10th Street 201,297 sf 4.3% $88.56 of AVERAGE VACANCY RATE Inventory ASKING NET RENT OCEAN DRIVE - Between 5th Street and 15th Street. 165,768 sf $97.53 of 3.0% VACANCY RATE AVERAGE Inventory ASKING NET RENT MIRACLE MILE - Between Le Jeune Rd. and Douglas Rd. 440,886 sf $44.60 of 6.2% VACANCY RATE AVERAGE Inventory ASKING NET RENT LAS OLAS BOULEVARD - Between SE 6th Ave. to SE 16th Ave. 367,803 sf 5.3% $36.17 of AVERAGE VACANCY RATE Inventory ASKING NET RENT CLEMATIS STREET - Between Olive Ave. and Quadrille Blvd. 329,086 sf $23.22 of 12.2% VACANCY RATE AVERAGE Inventory ASKING NET RENT WORTH AVENUE - Between Ocean Blvd. and Coconut Row 319,387 sf $75.61 of 2.4% AVERAGE VACANCY RATE Inventory ASKING NET RENT FLAGLER STREET - Between Biscayne Blvd. and NW First Ave. 372,541 sf $29.25 of 10.1% VACANCY RATE AVERAGE Inventory ASKING NET RENT SOUTH MIAMI - Between US-1 and SW 57th Ave. 244,082 sf 0% N/A of AVERAGE Inventory VACANCY RATE ASKING NET RENT TAKING TO THE STREET: URBAN RETAILSCAPE IN SOUTH FLORIDA Occupancy and asking rents have renovation and revival, compared to kept an upward trend in South the other streets. -

14Th Street Line Find the Stop at Or Nearest the Point Where You Will Get on the Bus

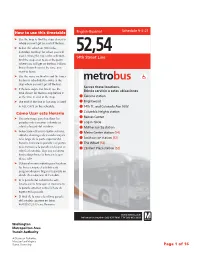

Schedule 9-5-21 How to use this timetable ➤ Use the map to find the stops closest to where you will get on and off the bus. ➤ Select the schedule (Weekday, Saturday, Sunday) for when you will 52,54 travel. Along the top of the schedule, 14th Street Line find the stop at or nearest the point where you will get on the bus. Follow that column down to the time you want to leave. ➤ Use the same method to find the times the bus is scheduled to arrive at the stop where you will get off the bus. Serves these locations- ➤ If the bus stop is not listed, use the Brinda servicio a estas ubicaciones time shown for the bus stop before it as the time to wait at the stop. l Takoma station ➤ The end-of-the-line or last stop is listed l Brightwood in ALL CAPS on the schedule. l 14th St. and Colorado Ave. N.W. l Columbia Heights station Cómo Usar este Horario Reeves Center ➤ Use este mapa para localizar las l paradas más cercanas a donde se l Logan Circle subirá y bajará del autobús. l McPherson Sq station ➤ Seleccione el horario (Entre semana, l Metro Center station (54) sábado, domingo) de cuando viajará. A lo largo de la parte superior del l Smithsonian station (52) horario, localice la parada o el punto l The Wharf (52) más cercano a la parada en la que se l L’Enfant Plaza station (52) subirá al autobús. Siga esa columna hacia abajo hasta la hora en la que desee salir.