Tradition and Imagination in William Blake's Illustrations for the Book of Job

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Blake 1 William Blake

William Blake 1 William Blake William Blake William Blake in a portrait by Thomas Phillips (1807) Born 28 November 1757 London, England Died 12 August 1827 (aged 69) London, England Occupation Poet, painter, printmaker Genres Visionary, poetry Literary Romanticism movement Notable work(s) Songs of Innocence and of Experience, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, The Four Zoas, Jerusalem, Milton a Poem, And did those feet in ancient time Spouse(s) Catherine Blake (1782–1827) Signature William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age. His prophetic poetry has been said to form "what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language".[1] His visual artistry led one contemporary art critic to proclaim him "far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced".[2] In 2002, Blake was placed at number 38 in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.[3] Although he lived in London his entire life except for three years spent in Felpham[4] he produced a diverse and symbolically rich corpus, which embraced the imagination as "the body of God",[5] or "Human existence itself".[6] Considered mad by contemporaries for his idiosyncratic views, Blake is held in high regard by later critics for his expressiveness and creativity, and for the philosophical and mystical undercurrents within his work. His paintings William Blake 2 and poetry have been characterised as part of the Romantic movement and "Pre-Romantic",[7] for its large appearance in the 18th century. -

Guy Peppiatt Fine Art British Portrait and Figure

BRITISH PORTRAIT AND FIGURE DRAWINGS 2020 BRITISH PORTRAIT AND FIGURE DRAWINGS BRITISH PORTRAIT AND FIGURE DRAWINGS 2020 GUY PEPPIATT FINE ART FINE GUY PEPPIATT GUY PEPPIATT FINE ART LTD Riverwide House, 6 Mason’s Yard Duke Street, St James’s, London SW1Y 6BU GUY PEPPIATT FINE ART Guy Peppiatt started his working life at Dulwich Picture Gallery before joining Sotheby’s British Pictures Department in 1993. He soon specialised in early British drawings and watercolours and took over the running of Sotheby’s Topographical sales. Guy left Sotheby’s in 2004 to work as a dealer in early British watercolours and since 2006 he has shared a gallery on the ground floor of 6 Mason’s Yard off Duke St., St. James’s with the Old Master and European Drawings dealer Stephen Ongpin. He advises clients and museums on their collections, buys and sells on their behalf and can provide insurance valuations. He exhibits as part of Master Drawings New York every January as well as London Art Week in July and December. Email: [email protected] Tel: 020 7930 3839 or 07956 968 284 Sarah Hobrough has spent nearly 25 years in the field of British drawings and watercolours. She started her career at Spink and Son in 1995, where she began to develop a specialism in British watercolours of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In 2002, she helped set up Lowell Libson Ltd, serving as co- director of the gallery. In 2007, Sarah decided to pursue her other passion, gardens and plants, and undertook a post graduate diploma in landscape design. -

Drawing After the Antique at the British Museum

Drawing after the Antique at the British Museum Supplementary Materials: Biographies of Students Admitted to Draw in the Townley Gallery, British Museum, with Facsimiles of the Gallery Register Pages (1809 – 1817) Essay by Martin Myrone Contents Facsimile, Transcription and Biographies • Page 1 • Page 2 • Page 3 • Page 4 • Page 5 • Page 6 • Page 7 Sources and Abbreviations • Manuscript Sources • Abbreviations for Online Resources • Further Online Resources • Abbreviations for Printed Sources • Further Printed Sources 1 of 120 Jan. 14 Mr Ralph Irvine, no.8 Gt. Howland St. [recommended by] Mr Planta/ 6 months This is probably intended for the Scottish landscape painter Hugh Irvine (1782– 1829), who exhibited from 8 Howland Street in 1809. “This young gentleman, at an early period of life, manifested a strong inclination for the study of art, and for several years his application has been unremitting. For some time he was a pupil of Mr Reinagle of London, whose merit as an artist is well known; and he has long been a close student in landscape afer Nature” (Thom, History of Aberdeen, 1: 198). He was the third son of Alexander Irvine, 18th laird of Drum, Aberdeenshire (1754–1844), and his wife Jean (Forbes; d.1786). His uncle was the artist and art dealer James Irvine (1757–1831). Alexander Irvine had four sons and a daughter; Alexander (b.1777), Charles (b.1780), Hugh, Francis, and daughter Christian. There is no record of a Ralph Irvine among the Irvines of Drum (Wimberley, Short Account), nor was there a Royal Academy student or exhibiting or listed artist of this name, so this was surely a clerical error or misunderstanding. -

Cat Talogu E 57

Grosvenor Prints 19 Shelton Street Covent Garden London WC2H 9JN Tel: 020 7836 1979 Fax: 020 7379 6695 E-mail: [email protected] www.grosvenorprints.com Dealers in Antique Prints & Books Catalogue 57 Item 50: George Stubbs. Phillis. A Pointer of Lord Clermonts. All items listed are illustrated on our web site: www.grosvenorprints.com Registered in England No. 1305630 Registered Office: 2, Castle Business Villlage, Station Roaad, Hampton, Middlesex. TW12 2BX. Rainbrook Ltd. Directors: N.C. Talbot. T.D.M. Rayment. C.E. Elliis. E&OE VAT No. 217 6907 49 ARTS 1. [Shepherd resting in a field.] Engraving, sheet 440 x 550mm (17½ x 21½"). Boyne [by John Boyne, 1806] Trimmed inside platemark; repaired tear at top. Foxed. Pen lithograph, sheet 225 x 310mm (8¾ x 12½"). Celadon at the centre, looking to the heavens with his Glued to original backing sheet at top corners with arms outstretched in disbelief and grief; Amelia lies printed border. Foxing. £450 dead at his feet. In the background a house with a Early lithograph by John Boyne (1750s-1810), Irish shepherd driving his sheep up a hill, on which is a watercolour painter and engraver who lived a colourful fortress. To right, a bay with stormy seas and a broken and varied life. After moving to England at 9 years old bridge. Verse from 'Summer' by James Thomson from and serving an apprenticeship to engraver William his 'The Seasons' below. Byrne, Boyne soon gave up printmaking to join a After an unlocated painting by Richard Wilson (1714 - company of strolling actors in Essex. -

Blake 250 Programme A4

Marking the 250th anniversary of the birth of William Blake William Blake’s Divine Humanity a dramatisation of Blake’s life & work Souvenir Programme THE NEW PLAYERS THEATRE The Arches, Villiers Street, London wc2 6ng (Charing Cross) 20 November – 02 December 2007 A THEATRE OF ETERNAL VALUES PRODUCTION An introduction Founded in 1996 Theatre of Eternal Values is a haven for an expanding international group of actors, dancers, singers, writers, directors and designers dedicated to artistic and spiritual growth. It is a place for emerging talent and seasoned professionals to explore and to practice their craft, and perhaps find new inspiration. Although TEV performs principally – but not exclusively – in the English language, the aim is to assimilate the cultural strengths of the group in every production. The Company is dedicated to the belief that creative and revelatory voices (past and present) need to be heard, developed and experienced live! We believe that theatre reinforces Photo: Peter Ashworth our psychological self-immune system and enhaces the balance and self-awareness of the community. Foreword From 1996-2007 TEV has created eleven productions: two international touring shows – Moliere’s William Blake is the great liberator of the imagination. His writing has The Imaginary Invalid and Mozart’s Magic Flute – and nine national shows produced by TEV artists unrelenting cerebral firepower; kinetic energy captured in words, in Austria, Canada, Germany, Italy and the UK. As the theatre company has grown and eighteenth century rock’n’roll and then some. Academics labour hard flourished, educational training programs and workshops have been a natural offshoot of our to unlock his secrets, each falling into the very trap that Blake has set national and international productions. -

Blake & Shakespeare

Interfaces Image Texte Language 38 | 2017 Crossing Borders: Appropriations and Collaborations Blake & Shakespeare Michael Phillips Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/interfaces/319 DOI: 10.4000/interfaces.319 ISSN: 2647-6754 Publisher: Université de Bourgogne, Université de Paris, College of the Holy Cross Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 2017 Number of pages: 157-172 ISSN: 1164-6225 Electronic reference Michael Phillips, “Blake & Shakespeare”, Interfaces [Online], 38 | 2017, Online since 13 June 2018, connection on 07 January 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/interfaces/319 ; DOI: https:// doi.org/10.4000/interfaces.319 Les contenus de la revue Interfaces sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. 157 BLAKE & SHAKESPEARE Michael Phillips On 12 September 1800 Blake wrote to his close friend, the sculptor John Flaxman, to thank him for his help in introducing him to a new patron at a time that he was in need of work: I send you a few lines which I hope you will Excuse. And As the time is now arrived when Men shall again converse in Heaven & walk with Angels[,] I know you will be pleased with the Intention & hope you will forgive the Poetry. (Blake to John Flaxman, September 12, 1800) What follows is a verse autobiography of Blake’s early life. For a poet whom few would normally associate with Shakespeare, it is revealing: To My Dearest Friend John Flaxman Now my lot in the Heavens is this; Milton lovd me in childhood & shewd me his face. Ezra came with Isaiah the Prophet, but Shakespeare in riper years gave me his hand Paracelsus & Behmen appeard to me. -

A Stylistic Analysis of Ekphrastic Poetry in English

T.C ANKARA ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ BATI DİLLERİ VE EDEBİYATLARI İNGİLİZ DİLİ VE EDEBİYATI A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF EKPHRASTIC POETRY IN ENGLISH PhD Dissertation Berkan ULU Ankara-2010 T.C ANKARA ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ BATI DİLLERİ VE EDEBİYATLARI İNGİLİZ DİLİ VE EDEBİYATI A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF EKPHRASTIC POETRY IN ENGLISH PhD Dissertation Berkan ULU Advisor Asst.Prof.Dr.Nazan TUTAŞ Ankara-2010 T.C ANKARA ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ BATI DİLLERİ VE EDEBİYATLARI İNGİLİZ DİLİ VE EDEBİYATI A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF EKPHRASTIC POETRY IN ENGLISH PhD Dissertation Advisor : Asst. Prof. Dr. Nazan TUTAŞ Members of the PhD Committee Name and Surname Signature Prof. Dr. Belgin ELBİR ........................................ Prof. Dr. Ufuk Ege UYGUR ........................................ Assoc. Prof. Dr. Lerzan GÜLTEKİN ........................................ Asst. Prof. Dr. Nazan TUTAŞ (Advisor) ......................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Trevor HOPE ......................................... Date .................................. TÜRKİYE CUMHURİYETİ ANKARA ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ MÜDÜRLÜĞÜNE Bu belge ile, bu tezdeki bütün bilgilerin akademik kurallara ve etik davranış ilkelerine uygun olarak toplanıp sunulduğunu beyan ederim. Bu kural ve ilkelerin gereği olarak, çalışmada bana ait olmayan tüm veri, düşünce ve sonuçları andığımı ve kaynağını gösterdiğimi ayrıca beyan ederim.(……/……/200…) …………………………………… Berkan ULU ABSTRACT “A Stylistic Anlaysis of Ekphrastic Poetry in English” -

Prints on Display: Exhibitions of Etching and Engraving in England, 1770S-1858

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2018 Prints on Display: Exhibitions of Etching and Engraving in England, 1770s-1858 Nicole Simpson The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2501 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] PRINTS ON DISPLAY: EXHIBITIONS OF ETCHING AND ENGRAVING IN ENGLAND, 1770S-1858 by NICOLE SIMPSON A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 NICOLE SIMPSON All Rights Reserved ii Prints on Display: Exhibitions of Etching and Engraving in England, 1770s-1858 by Nicole Simpson This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Katherine Manthorne Chair of Examining Committee Date Rachel Kousser Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Patricia Mainardi Diane Kelder Cynthia Roman THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Prints on Display: Exhibitions of Etching and Engraving in England, 1770s-1858 by Nicole Simpson Advisor: Katherine Manthorne During the long nineteenth century, in cities throughout Europe and North America, a new type of exhibition emerged – exhibitions devoted to prints. Although a vital part of print culture, transforming the marketing and display of prints and invigorating the discourse on the value and status of printmaking, these exhibitions have received little attention in existing scholarship. -

Antiquarian Topographical Prints & Drawings 1550-1850

Antiquarian Topographical Prints 1550-1850 (As they relate to castle studies) Antiquarian Topographical Prints & Drawings 1550-1850 (as they relate to castles) Part One: Introduction - 1550-1790 ‘Bringing Truth to Light’ Samuel Hieronymous Grimm, c. 1784. ‘The Entrance to the Prison Chamber at Lincoln, under the NW tower of the cathedral’. One man is shown holding the ladder while others, adventurous antiquaries, cautiously climb up and in through the narrow entrance to explore the chamber. © The British Library Board. Shelfmark: Additional MS 15541 Item number: f.79 1 Antiquarian Topographical Prints 1550-1850 (As they relate to castle studies) Antiquarian Topographical Prints & Drawings 1550-1850 (as they relate to castles) Part One Frontispiece: Dover (the north barbican), ‘The History of Dover Castle’, by the Revd: Wm. Darell Chaplain to Queen Elizabeth. Illustrated with 10 Views, and a Plan of the Castle. William Darell. Hooper and Wigstead, London 1797. Introduction - The Art of Topography 3-12 Catalogue - Part One John Speed 13 John Norden 14-16 Anton van den Wyngaerde 17 Ralph Agas 18 George Braun & Frans Hogenberg 18-19 William Smith 20 William Haiward 21 John Bereblock 22 Cornelis Bol 22 Daniel King 23-24 Wenceslaus Hollar 25-29 Alexander Keirincx 30 Hendrick Danckerts 31-32 Willem Schellinks 33 John Slezer 34 Francis Place 35-40 Michael Burghers 41 Jan Kip & Leonard Knyff 42-43 Robert Harman 44 William Stukeley 45-46 Bernard Lens III 47 Antonio Canaletto 47-48 Samuel & Nathaniel Buck 50-57 George Vertue 58-63 William Borlase 64 Thomas Badeslade 65-66 Francis Grose 67-70 Edward King 71-74 Women antiquaries and restorers: 75-81 Lady Anne Clifford; The Frankland sisters; Miss H. -

The Old Engravers of England in Their Relation to Contemporary Life and Art

7 VI l ^ >. I } A_/ OLD ENGRAVERS OF ENGLAND MALCOLM C. ALAMAN THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES 60 g _ t- .aC !3 C a tf * Pi 3*1 ,.* Zp C $ o g* - S o, o g^TS-i '^ o a II3 - ^ C) Cfl ** S .S 3 2 33 w ^ 111 s -a o> It >^ S ^^ Bjsnsn *d ^a* s g o> .a .11 *J o M o -c b ^H iliaiei!CT-S 6042 fl T*- PH 3 -5 .S -3 a^ i-a H *- O .^ o W 5< *-* t5 ^ w S S c ' c i i S 2 .2 e-S 1.^ 5 IH <-! a 'S .5 c o T3 .2 M rf-S -ll P Q\C 5i 3 ^^ c - S ^.o g,^ c g 5^ ) .2 S -3 ^s15 | 'S 5 fe -S o s . fc " a W O3 V< rt flj a 0) O I" e o iJ'-^ft- P O O ^, C 0) r* O3 S,' > s! >> >>.*3 fi 3 111 II J $e on gts'8o be - O O O D, * 45 .fa "5 ^ ^ 1 J 2 *2 T3 MS o ri a S g-S CO CO _2? 2 73 1 | t<I i !58 1"H ~ g, P o S ll|ia--j3 d -S t: | 1 0) >> c -^ .ti tilii* M 5 3 3 o cr 2o. ' 5 2 ^^ C JJ ^ ^ 5 spll^lllSilllO O cd ill^iiiii ^8^ i . w w ,2 c 4J Jj*o S "SIS-* -S JJ o ". S^ to 1 < >^ co i 8 2 3 *i: -J .en *s" mi's 3c <u =33 * .s- '! ,S i e c 'in> cd Irt & ^3 3 rt O% <* *- OD o SiP* a c aS o -o s"2 -6-P! M ^ 3 S ^ ^ i .5 o i^s Sg 2 Sw -5 |*fS cr rf c P 3 , Z2 ' 3S H C = S S <u J3 >> ^^2 rt 1*0 | 3 :K5 ol> Sal "53 :: J3 o ^11 ^ S fe 3 .5 g t. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Portraits of patients and sufferers in Britain, c. 1660-c. 1850 James, Douglas Hugh Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 10. Oct. 2021 This electronic theses or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Portraits of patients and sufferers in Britain, c. -

Master Thesis

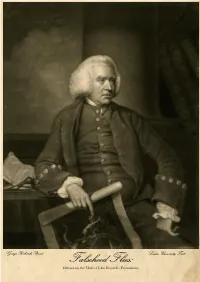

Falsehood Flies: Debunking the myth of John Boydell’s printmaking George Richards (s1382330) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for graduation with Master of Arts From the department of Arts and Culture: Early Modern and Medieval Art Thesis Supervisors: Professor Caroline van Eck Drs. Nelke Bartelings 5794VMATH September 30th, 2014 University of Leiden Cover Image: Valentine Green after Josiah Boydell. John Boydell, Engraver, mezzotint, 1772. Trustees of the British Museum. Acknowledgements To begin with, I would like to acknowledge my debt to the late Christopher Lennox-Boyd. His enthusiasm for the graphic arts was infectious, and first stoked my interest in this field. A connoisseur of true anachronism; the scope of his knowledge was rivalled only by that of his collection. Were it not for his influence, this thesis would never have been realised. It was an honour to have known him. The same may be said for Professor Caroline van Eck and Drs. Nelke Bartelings. With Caroline’s command of the long eighteenth-century, and Nelke’s encyclopaedic grasp of printmaking, the pair of them suggested important revisions which shaped the final version of this work. I could not have asked for more valuable supervision. On a more intimate level, I must thank my parents, who provided unwavering counsel, as well as an efficient courier service. Additional mention should also go to the Greek contingent of Constantina, Stefanos, and Panagiota, who ensured that I balanced industry with idleness during my stay in Leiden. And finally, I extend a special gratitude to my dearest Monique. She has had the patience of Elizabeth Boydell from the very outset, and suppressed any hint of rancour as I recently spent our holiday in Burgundy by writing my appendices.