Prostrate Knotweed Polygonum Aviculare L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stace Edition 4: Changes

STACE EDITION 4: CHANGES NOTES Changes to the textual content of keys and species accounts are not covered. "Mention" implies that the taxon is or was given summary treatment at the head of a family, family division or genus (just after the key if there is one). "Reference" implies that the taxon is or was given summary treatment inline in the accounts for a genus. "Account" implies that the taxon is or was given a numbered account inline in the numbered treatments within a genus. "Key" means key at species / infraspecific level unless otherwise qualified. "Added" against an account, mention or reference implies that no treatment was given in Edition 3. "Given" against an account, mention or reference implies that this replaces a less full or prominent treatment in Stace 3. “Reduced to” against an account or reference implies that this replaces a fuller or more prominent treatment in Stace 3. GENERAL Family order changed in the Malpighiales Family order changed in the Cornales Order Boraginales introduced, with families Hydrophyllaceae and Boraginaceae Family order changed in the Lamiales BY FAMILY 1 LYCOPODIACEAE 4 DIPHASIASTRUM Key added. D. complanatum => D. x issleri D. tristachyum keyed and account added. 5 EQUISETACEAE 1 EQUISETUM Key expanded. E. x meridionale added to key and given account. 7 HYMENOPHYLLACEAE 1 HYMENOPHYLLUM H. x scopulorum given reference. 11 DENNSTAEDTIACEAE 2 HYPOLEPIS added. Genus account added. Issue 7: 26 December 2019 Page 1 of 35 Stace edition 4 changes H. ambigua: account added. 13 CYSTOPTERIDACEAE Takes on Gymnocarpium, Cystopteris from Woodsiaceae. 2 CYSTOPTERIS C. fragilis ssp. fragilis: account added. -

Application of Pontentilla Anserine, Polygonum Aviculare and Rumex Crispus Mixture Extracts in a Rabbit Model with Experimentally Induced E

animals Article Application of Pontentilla Anserine, Polygonum aviculare and Rumex Crispus Mixture Extracts in A Rabbit Model with Experimentally Induced E. coli Infection Robert Kupczy ´nski 1,* , Antoni Szumny 2 , Michał Bednarski 3, Tomasz Piasecki 3, Kinga Spitalniak-Bajerska´ 1 and Adam Roman 1 1 Department of Environment, Animal Hygiene and Welfare, Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences, 51-630 Wrocław, Poland; [email protected] (K.S.-B.);´ [email protected] (A.R.) 2 Department of Chemistry, Wroclaw University of Environmental and Life Science, 50-375 Wrocław, Poland; [email protected] 3 Department of Epizootiology with Clinic of Birds and Exotic Animals, Wroclaw University of Environmental and Life Science, 50-366 Wrocław, Poland; [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (T.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 27 September 2019; Accepted: 7 October 2019; Published: 9 October 2019 Simple Summary: The beneficial effect of herbs on production parameters, quality of products of animal origin, and animal health was demonstrated in numerous studies. This study aimed to determine an effect of herbal mixture on blood parameters and the anti-colibacteriosis efficacy. The rabbit model used during the experimental infection with E. coli indicates a clear effect of Rumex crispus L., Pontentilla anserine, Polygonum aviculare, whose activity involves the reduction of colonization of basically all sections of the intestines. The use of herbs in rabbits can control the activity of intestinal microbial community. Administration of a mixture of herbs to feed reduced the number of E. coli in cecum more than supplementation into water after experimental infection. -

Vegetation and Ecological Characterisitics of Mixed-Conifer

Vegetation and Ecological Charactistics of Mixed-Conifer and Red Fir Forests at the Teakettle Experimental Forest Vegetation and Ecological Characteristics of Mixed-Conifer and Red Fir Forests at the Teakettle Experimental Forest Appendix B: Plant List A total of 152 plants found at the Teakettle Experimental Forest, 80 km east of Fresno, California, by scientific name, common name, and abbreviation used in the text. The list is alphabetically sorted by genus and species. Family Genus species var/ssp Common name Abbre. in text Pinaceae Abies concolor white fir ABCO Pinaceae Abies magnifica red fir ABMA Asteraceae Achillea lanulosa yarrow Asteraceae Achillea millefolium yarrow Asteraceae Adenocaulon bicolor trail plant Asteraceae Agroseris retrorsa spear-leaved agoseris Polemoniaceae Allophylum intregifolium allophylum Asteraceae Anaphalis margaritacea pearly everlasting Apocynaceae Apocynum androsaemifolium dogbane APAN Ranunculaceae Aquilegia formosa columbine AQFO Brassicaceae Arabis platysperma platysperma rock cress ARPL Brassicaceae Arabis rectissima rectissima bristly-leaved rock cress Brassicaceae Arabis repanda repanda repand rock cress Ericaceae Arctostaphylus nevadensis pinemat manzanita ARNE Ericaceae Arctostaphylus patula greenleaf manzanita ARPA Caryophyliaceae Arenaria kingii sandwort Asteraceae Aster foliaceus leafy aster ASFO Asteraceae Aster occidentalis occidentalis western mountain aster ASOC Fabaceae Astragalus bolanderi Bolander’s locoweed ASBO Dryopteridaceae Athryium felix-femina lady fern ATFI Liliaceae Brodiaea elegans elegans harvest brodeia Poaceae Bromus ssp. brome Cupressaceae Calocedrus decurrens incense cedar CADE Liliaceae Calochortus leichtlinii Leichtlin’s mariposa lily CALE Portulacaceae Calyptridium umbellatum pussy paws CAUM Convuvulaceae Calystegia malacophylla morning glory CAMA Brassicaceae Cardamine breweri breweri (continues on next page) 46 USDA Forest Service Gen.Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-186. 2002. USDA Forest Service Gen.Tech. Rep. -

Polygonaceae of Alberta

AN ILLUSTRATED KEY TO THE POLYGONACEAE OF ALBERTA Compiled and writen by Lorna Allen & Linda Kershaw April 2019 © Linda J. Kershaw & Lorna Allen This key was compiled using informaton primarily from Moss (1983), Douglas et. al. (1999) and the Flora North America Associaton (2005). Taxonomy follows VAS- CAN (Brouillet, 2015). The main references are listed at the end of the key. Please let us know if there are ways in which the kay can be improved. The 2015 S-ranks of rare species (S1; S1S2; S2; S2S3; SU, according to ACIMS, 2015) are noted in superscript (S1;S2;SU) afer the species names. For more details go to the ACIMS web site. Similarly, exotc species are followed by a superscript X, XX if noxious and XXX if prohibited noxious (X; XX; XXX) according to the Alberta Weed Control Act (2016). POLYGONACEAE Buckwheat Family 1a Key to Genera 01a Dwarf annual plants 1-4(10) cm tall; leaves paired or nearly so; tepals 3(4); stamens (1)3(5) .............Koenigia islandica S2 01b Plants not as above; tepals 4-5; stamens 3-8 ..................................02 02a Plants large, exotic, perennial herbs spreading by creeping rootstocks; fowering stems erect, hollow, 0.5-2(3) m tall; fowers with both ♂ and ♀ parts ............................03 02b Plants smaller, native or exotic, perennial or annual herbs, with or without creeping rootstocks; fowering stems usually <1 m tall; fowers either ♂ or ♀ (unisexual) or with both ♂ and ♀ parts .......................04 3a 03a Flowering stems forming dense colonies and with distinct joints (like bamboo -

Fallopia Japonica – Japanese Knotweed

Fallopia japonica – Japanese knotweed Japanese knotweed, sometimes referred to What is it? as donkey rhubarb for its sour red spring shoots, is a perennial plant in the Buckwheat family (Polygonaceae). It has large broad green leaves; tall, thick, sectioned and somewhat reddish zigzagging stems; and racemes of small papery flowers in summer. Photo by Liz West 2007 Other scientific names (synonyms) for Japanese knotweed are Reynoutria japonica and Polygonum cuspidatum. When does it grow? Shoots emerge from rhizomes (modified underground stems) from late March to mid-April. A spring freeze or deep frost can top kill new growth, but new shoots readily crop up from the hardy rootstalks. Growth continues rapidly once the weather begins to warm reaching heights up to 10 feet or greater by summer. R. Buczynski 2020 4.15.2020 Where is it from? Japanese knotweed is native to eastern Asia and was introduced to the United Kingdom in the 1800’s as a vigorous garden ornamental. Before becoming illegal to plant in England it was horticulturally introduced from the UK to the United States. Where is it now? Japanese knotweed has been reported extensively in the Northeastern U. S. and is currently present in all three counties (Hunterdon, Morris, and Somerset) within the upper Raritan watershed where it continues to spread into moist disturbed areas along waterways. Photo by Roger Kidd © Why is it invasive? Although knotweed can spread by seed, it is most effective at spreading underground via rhizomes that extend outward as well as downward, producing new shoots up to 70 feet away. If detached from the plant, small fragments of rhizome can survive and produce new plants wherever they land. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Alexey B. Shipunov Last revision: August 26, 2021 Contents 1 Degrees..........................................................1 2 Employment.......................................................1 3 Teaching and Mentoring Experience.........................................2 4 Awards and Funding..................................................3 5 Research Interests...................................................3 6 Research and Education Goals and Principles...................................4 7 Publications.......................................................5 8 Attended Symposia................................................... 17 9 Field Experience..................................................... 19 10 Service and Outreach.................................................. 19 11 Developing........................................................ 20 12 Professional Memberships............................................... 21 Personal Data Address Kyoto University, Univerity Museum, Yoshidahonmachi, Sakyo Ward, Kyoto, 606-8317, Japan E-mail [email protected] Fax +81 075–753–3277 Office tel. +81 075–753–3272 Web site http://ashipunov.info 1 Degrees 1998 Ph. D. (Biology), Moscow State University. Thesis title: Plantains (genera Plantago L. and Psyllium Mill., Plantaginaceae) of European Russia and adjacent territories (advisor: Dr. Vadim Tikhomirov; reviewers: Dr. Vladimir Novikov, Dr. Alexander Luferov) 1990 M. Sc. (Biology), Moscow State University. Thesis title: Knotweeds (Polygonum aviculare L. and allies) -

Botolph's Bridge, Hythe Redoubt, Hythe Ranges West And

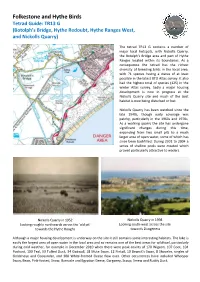

Folkestone and Hythe Birds Tetrad Guide: TR13 G (Botolph’s Bridge, Hythe Redoubt, Hythe Ranges West, and Nickolls Quarry) The tetrad TR13 G contains a number of major local hotspots, with Nickolls Quarry, the Botolph’s Bridge area and part of Hythe Ranges located within its boundaries. As a consequence the tetrad has the richest diversity of breeding birds in the local area, with 71 species having a status of at least possible in the latest BTO Atlas survey. It also had the highest total of species (125) in the winter Atlas survey. Sadly a major housing development is now in progress at the Nickolls Quarry site and much of the best habitat is now being disturbed or lost. Nickolls Quarry has been watched since the late 1940s, though early coverage was patchy, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s. As a working quarry the site has undergone significant changes during this time, expanding from two small pits to a much larger area of open water, some of which has since been backfilled. During 2001 to 2004 a series of shallow pools were created which proved particularly attractive to waders. Nickolls Quarry in 1952 Nickolls Quarry in 1998 Looking roughly northwards across the 'old pit' Looking south-west across the site towards the Hythe Roughs towards Dungeness Although a major housing development is underway on the site it still contains some interesting habitats. The lake is easily the largest area of open water in the local area and so remains one of the best areas for wildfowl, particularly during cold weather, for example in December 2010 when there were peak counts of 170 Wigeon, 107 Coot, 104 Pochard, 100 Teal, 53 Tufted Duck, 34 Gadwall, 18 Mute Swan, 12 Pintail, 10 Bewick’s Swan, 8 Shoveler, singles of Goldeneye and Goosander, and 300 White-fronted Geese flew over. -

Native Plant List CITY of OREGON CITY 320 Warner Milne Road , P.O

Native Plant List CITY OF OREGON CITY 320 Warner Milne Road , P.O. Box 3040, Oregon City, OR 97045 Phone: (503) 657-0891, Fax: (503) 657-7892 Scientific Name Common Name Habitat Type Wetland Riparian Forest Oak F. Slope Thicket Grass Rocky Wood TREES AND ARBORESCENT SHRUBS Abies grandis Grand Fir X X X X Acer circinatumAS Vine Maple X X X Acer macrophyllum Big-Leaf Maple X X Alnus rubra Red Alder X X X Alnus sinuata Sitka Alder X Arbutus menziesii Madrone X Cornus nuttallii Western Flowering XX Dogwood Cornus sericia ssp. sericea Crataegus douglasii var. Black Hawthorn (wetland XX douglasii form) Crataegus suksdorfii Black Hawthorn (upland XXX XX form) Fraxinus latifolia Oregon Ash X X Holodiscus discolor Oceanspray Malus fuscaAS Western Crabapple X X X Pinus ponderosa Ponderosa Pine X X Populus balsamifera ssp. Black Cottonwood X X Trichocarpa Populus tremuloides Quaking Aspen X X Prunus emarginata Bitter Cherry X X X Prunus virginianaAS Common Chokecherry X X X Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir X X Pyrus (see Malus) Quercus garryana Garry Oak X X X Quercus garryana Oregon White Oak Rhamnus purshiana Cascara X X X Salix fluviatilisAS Columbia River Willow X X Salix geyeriana Geyer Willow X Salix hookerianaAS Piper's Willow X X Salix lucida ssp. lasiandra Pacific Willow X X Salix rigida var. macrogemma Rigid Willow X X Salix scouleriana Scouler Willow X X X Salix sessilifoliaAS Soft-Leafed Willow X X Salix sitchensisAS Sitka Willow X X Salix spp.* Willows Sambucus spp.* Elderberries Spiraea douglasii Douglas's Spiraea Taxus brevifolia Pacific Yew X X X Thuja plicata Western Red Cedar X X X X Tsuga heterophylla Western Hemlock X X X Scientific Name Common Name Habitat Type Wetland Riparian Forest Oak F. -

Barrowhill, Otterpool and East Stour River)

Folkestone and Hythe Birds Tetrad Guide: TR13 D (Barrowhill, Otterpool and East Stour River) The tetrad TR13 D is an area of mostly farmland with several small waterways, of which the East Stour River is the most significant, and there are four small lakes (though none are publically-accessible), the most northerly of which is mostly covered with Phragmites. Other features of interest include a belt of trees running across the northern limit of Lympne Old Airfield (in the extreme south edge of the tetrad), part of Harringe Brooks Wood (which has no public access), the disused (Otterpool) quarry workings and the westernmost extent of Folkestone Racecourse and. The northern half of the tetrad is crossed by the major transport links of the M20 and the railway, whilst the old Ashford Road (A20), runs more or less diagonally across. Looking south-west towards Burnbrae from the railway Whilst there are no sites of particular ornithological significance within the area it is not without interest. A variety of farmland birds breed, including Kestrel, Stock Dove, Sky Lark, Chiffchaff, Blackcap, Lesser Whitethroat, Yellowhammer, and possibly Buzzard, Yellow Wagtail and Meadow Pipit. Two rapidly declining species, Turtle Dove and Spotted Flycatcher, also probably bred during the 2007-11 Bird Atlas. The Phragmites at the most northerly lake support breeding Reed Warbler and Reed Bunting. In winter Fieldfare and Redwing may be found in the fields, whilst the streams have attracted Little Egret, Snipe and, Grey Wagtail, with Siskin and occasionally Lesser Redpoll in the alders along the East Stour River. Corn Bunting may be present if winter stubble is left and Red Kite, Peregrine, Merlin and Waxwing have also occurred. -

Butterflies of Hungary

Butterflies of Hungary Naturetrek Tour Report 19 - 26 June 2012 Anomalous Blue Assmann's Fritillary Lesser Spotted Fritillary Privet Hawkmoth - Sphinx ligustr Report and images compiled by Paul Harmes Naturetrek Cheriton Mill Cheriton Alresford Hampshire SO24 0NG England T: +44 (0)1962 733051 F: +44 (0)1962 736426 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Butterflies of Hungary Tour Leaders: Paul Harmes Naturetrek Naturalist Gerard Gorman Local Guide & tour manager Participants: Sue Arnott Ian Arnott Harry Faull Lynda Hill David Hill Gloria King Martin King Helen McLaren Janet Proctor Chris Proctor Pauline Robinson Peter Webster Day 1 Tuesday 19th June Weather: Very hot and sunny The group were met at Budapest’s Ferihgy Airport by Gerard and Paul, our guides for the week. The plane arrived on time, and we soon had everyone aboard the minibus. Our cheerful and experienced driver, Istvan (Steve), loaded our luggage in the vehicle’s trailer, and got us on the road in very good time. We made only one stop on our way up to Aggtelek, at a motorway service area on the M3 near the village of Ludas. Here, we found our first moth, a tiny well marked Pyralid, Synaphe moldavica. There were also White Wagtails and Crested Larks. We continued our journey to the far north-eastern corner of Hungary, and along the way we added White Stork, male and female Western Marsh Harriers, Common Kestrel and, over a small lake, Common Tern. We arrived at the Hotel Cseppko, set within the Aggtelek National Park, and close to the village of the same name, at about 17-30hrs, to be greeted by a Large Tortoiseshell in the reception area. -

List of Plants for Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve

Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve Plant Checklist DRAFT as of 29 November 2005 FERNS AND FERN ALLIES Equisetaceae (Horsetail Family) Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum arvense Present in Park Rare Native Field horsetail Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum laevigatum Present in Park Unknown Native Scouring-rush Polypodiaceae (Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Cystopteris fragilis Present in Park Uncommon Native Brittle bladderfern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Woodsia oregana Present in Park Uncommon Native Oregon woodsia Pteridaceae (Maidenhair Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Argyrochosma fendleri Present in Park Unknown Native Zigzag fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cheilanthes feei Present in Park Uncommon Native Slender lip fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cryptogramma acrostichoides Present in Park Unknown Native American rockbrake Selaginellaceae (Spikemoss Family) Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella densa Present in Park Rare Native Lesser spikemoss Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella weatherbiana Present in Park Unknown Native Weatherby's clubmoss CONIFERS Cupressaceae (Cypress family) Vascular Plant Pinales Cupressaceae Juniperus scopulorum Present in Park Unknown Native Rocky Mountain juniper Pinaceae (Pine Family) Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies concolor var. concolor Present in Park Rare Native White fir Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies lasiocarpa Present -

The Taxonomic Consideration of Floral Morphology in the Persicaria Sect

pISSN 1225-8318 − Korean J. Pl. Taxon. 48(3): 185 194 (2018) eISSN 2466-1546 https://doi.org/10.11110/kjpt.2018.48.3.185 Korean Journal of RESEARCH ARTICLE Plant Taxonomy The taxonomic consideration of floral morphology in the Persicaria sect. Cephalophilon (Polygonaceae) Min-Jung KONG and Suk-Pyo HONG* Laboratory of Plant Systematics, Department of Biology, Kyung Hee University, Seoul 02447, Korea (Received 29 June 2018; Accepted 12 July 2018) ABSTRACT: A comparative floral morphological study of 19 taxa in Persicaria sect. Cephalophilon with four taxa related to Koenigia was conducted to evaluate the taxonomic implications. The flowers of P. sect. Ceph- alophilon have (four-)five-lobed tepals; five, six, or eight stamens, and one pistil with two or three styles. The size range of each floral characteristic varies according to the taxa; generally P. humilis, P. glacialis var. gla- cialis and Koenigia taxa have rather small floral sizes. The connate degrees of the tepal lobes and styles also vary. The tepal epidermis consists of elongated rectangular cells with variation of the anticlinal cell walls (ACWs). Two types of glandular trichomes are found. The peltate glandular trichome (PT) was observed in nearly all of the studied taxa. The PT was consistently distributed on the outer tepal of P. sect. Cephalophilon, while Koenigia taxa and P. glacialis var. glacialis had this type of trichome on both sides of the tepal. P. crio- politana had only long-stalked pilate-glandular trichomes (LT) on the outer tepal. The nectary is distributed on the basal part of the inner tepal, with three possible shapes: dome-like, elongated, and disc-like nectary.