Kirkmichael to Spittal of Glenshee Place Names of the Cateran Trail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perth and Kinross Council Development Control Committee – 17 August 2011 Report of Handling by Development Quality Manager

4(3)(ii) 11/396 Perth and Kinross Council Development Control Committee – 17 August 2011 Report of Handling by Development Quality Manager Erection of 12 affordable (one bedroom) flats, Perth and Kinross Council, Rie- Achan Road, Pitlochry, PH16 5AL Ref. No: 11/01117/FLL Ward No: 4 - Highland Summary This report recommends approval of the application for the erection of 12 affordable flats as the revised design and scale of the building is considered to relate well with the surrounding features of the Conservation Area and the proposal is considered to comply with the provisions of the Development Plan. This proposal is considered to address the reasons for refusal of the previous application (11/00023/FLL). BACKGROUND AND DESCRIPTION 1 Full planning consent is sought for the erection of 12 affordable flats at the site of a former Perth and Kinross Council building at Dalchanpaig on Rie- Achan Road in Pitlochry. The application site is located within Pitlochry Conservation Area. The application site is owned by Perth and Kinross Council and as such there is a requirement for this application to be referred to the Development Control Committee. This application is a follow up to a previous refusal (11/00023/FLL). That application was refused at the Development Control Committee on 13 April 2011. The grounds for refusal included the design, materials and detrimental impact on the visual amenity and the failure to protect or enhance the Conservation Area. 2. The application site is situated on Rie-Achan Road which sits to the south of Atholl Road, the main road through Pitlochry. -

Highland Perthshire Trail

HIGHLAND PERTHSHIRE TRAIL HISTORY, CULTURE AND LANDSCAPES OF HIGHLAND PERTHSHIRE THE HIGHLAND PERTHSHIRE TRAIL - SELF GUIDED WALKING SUMMARY Discover Scotland’s vibrant culture and explore the beautiful landscapes of Highland Perthshire on this gentle walking holiday through the heart of Scotland. The Perthshire Trail is a relaxed inn to inn walking holiday that takes in the very best that this wonderful area of the highlands has to offer. Over 5 walking days you will cover a total of 55 miles through some of Scotland’s finest walking country. Your journey through Highland Perthshire begins at Blair Atholl, a small highland village nestled on the banks of the River Garry. From Blair Atholl you will walk to Pitlochry, Aberfeldy, Kenmore, Fortingall and then to Kinloch Rannoch. Several rest days are included along the way so that you have time to explore the many visitor attractions that Perthshire has to offer the independent walker. Every holiday we offer features hand-picked overnight accommodation in high quality B&B’s, country inns, and guesthouses. Each is unique and offers the highest levels of welcome, atmosphere and outstanding local cuisine. We also include daily door to door baggage transfers, route notes and detailed maps and Tour: Highland Perthshire Trail pre-departure information pack as well as emergency support, should you need it. Code: WSSHPT1—WSSHPT2 Type: Self-Guided Walking Holiday Price: See Website HIGHLIGHTS Single Supplement: See Website Dates: April to October Walking Days: 5—7 Exploring Blair Castle, one of Scotland’s finest, and the beautiful Atholl Estate. Nights: 6—8 Start: Blair Atholl Visiting the fascinating historic sites at the Pass of Killiecrankie and Loch Tay. -

The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, C.1164-C.1560

1 The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560 Victoria Anne Hodgson University of Stirling Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2016 2 3 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the Cistercian abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560, and its place within Scottish society. The subject of medieval monasticism in Scotland has received limited scholarly attention and Coupar itself has been almost completely overlooked, despite the fact that the abbey possesses one of the best sets of surviving sources of any Scottish religious house. Moreover, in recent years, long-held assumptions about the Cistercian Order have been challenged and the validity of Order-wide generalisations disputed. Historians have therefore highlighted the importance of dedicated studies of individual houses and the need to incorporate the experience of abbeys on the European ‘periphery’ into the overall narrative. This thesis considers the history of Coupar in terms of three broadly thematic areas. The first chapter focuses on the nature of the abbey’s landholding and prosecution of resources, as well as the monks’ burghal presence and involvement in trade. The second investigates the ways in which the house interacted with wider society outside of its role as landowner, particularly within the context of lay piety, patronage and its intercessory function. The final chapter is concerned with a more strictly ecclesiastical setting and is divided into two parts. The first considers the abbey within the configuration of the Scottish secular church with regards to parishes, churches and chapels. The second investigates the strength of Cistercian networks, both domestic and international. -

Buy Your Next Home with Next Home Leading Perthshire Estate Agency

Buy your next home with Next Home Leading Perthshire Estate Agency 2 Monks Way, Coupar Angus, Blairgowrie, PH13 9HW £170,000 Many thanks for your interest in We offer free, no obligation mortgage 2 Monks Way, Coupar Angus, Blairgowrie, advice to all our buyers. PH13 9HW. Buying with If you have a property to sell contact us Next Home Estate Agents dedicate to arrange a valuation. We are known in themselves to be available when you are, getting our customers moving quicker and offering an unbeatable service 7 days a at a higher price than our competitors. Put Next Home week until 9pm. us to the test and get your free valuation today, call 01764 42 43 44. 2 Monks Way, Coupar Angus, Blairgowrie, We have the largest sales team in Perthshire, operating from our 5 offices If you would like to kept informed of other PH13 9HW throughout Perthshire and delivering more great properties like this one please sales than any other estate agent. register on our hot buyers list, where we will email you of new property listings and Not only are we Perthshire’s Number 1 property open days. choice but we are also local. One of the reasons we know the local markets so well is because we live here. So let us guide you through the selling and buying process. If you’re a first time buyer we have incentives to help get you onto the property ladder our consultants can advise you through the whole process. Next Home - 2 Monks Way, Coupar Angus, Blairgowrie, PH13 9HW 2 About the area Blairgowrie is a thriving town with the High Street being the focal point having a variety of local shops including a butcher, book shop, antique and local craft and gift shops together with well-known department stores and supermarkets. -

Service 27 Bus Timetable

Service Perth - Pitlochry 27 (PKAO027) Monday to Friday (Outbound) Operated by: SPH Stagecoach Perth, Enquiry Phone Number: 01738 629339 Service: 27 27 27 27 Notes: SD Notes: XPrd1 Operator: SPH SPH SPH SPH Perth, Stance 5 Bus Station on Leonard Street Depart: T .... .... .... 18:20 Perth, Stop F Mill Street T .... .... .... 18:27 North Muirton, at Holiday Inn on Dunkeld Road T .... .... .... 18:35 North Muirton, at Inveralmond House on Auld Mart Road T 06:05 .... .... 18:37 Inveralmond, at Bus Depot on Ruthvenfield Road Depart: T .... 06:57 07:07 .... Bankfoot, at Garry Place on Prieston Road T .... .... .... 18:48 Bankfoot, at Prieston Road on Main Street T 06:16 07:08 07:18 18:50 Waterloo, opp Post Box on Dunkeld Road T 06:19 07:12 07:22 18:54 Birnam, opp Birnam Hotel on Perth Road T 06:27 07:20 07:30 19:03 Dunkeld, at North Car Park on Atholl Street T 06:30 07:23 07:33 19:06 Kindallachan, Northbound Bus Bay on A9 T 06:40 07:33 07:43 19:16 Ballinluig, at Tulliemet Road End on A827 T 06:45 07:38 07:48 19:21 Milton of Edradour, opp East Haugh on Old A9 T 06:50 07:43 .... 19:26 Pitlochry, at Fishers Hotel on Atholl Road T 06:55 07:48 .... 19:31 Pitlochry, at West End Car Park Arrive: T 06:56 07:49 .... 19:32 SD School days only. XPrd1 Does not operate on these dates: 03/07/2015 to 17/08/2015 10/09/2015 to 25/10/2015 19/11/2015 to 22/11/2015 19/12/2015 to 04/01/2016 17/02/2016 to 21/02/2016 25/03/2016 to 28/03/2016 02/04/2016 to 18/01/2038 Timetable valid from 26 Dec 2014 until further notice Generated by Trapeze Group © 06/07/2015 20:18. -

Coupar Angus Best Ever Cycling Festival

CANdo Coupar Angus and District Community Magazine ‘Eighth in the top ten healthiest places to live in the UK’ Coupar Angus best ever Cycling Festival ISSUE 90 July/August 2019 Joe Richards Collectables WANTED: Old tools & coins, Tilley lamps, war items 01828 628138 or 07840 794453 [email protected] Ryan Black, fish merchant in Coupar Bits n Bobs with Kids and Gifts Angus & area, Thursdays 8.30 am till 5 pm. At The Cross 12 till 12.45 ‘straight from the shore to your door’ CANdo July/August 2019 Editorial The other day I came across an interesting statistic, which you may have read in the local and national press. Apparently, Coupar Angus is one of the healthiest of places to live in the UK. It came eighth in a list of the top ten. You may view this with some scepticism - why not in the top three? Or with surprise that our town is mentioned at all. Further investigation revealed how the list was compiled. It comes from Liverpool University and the Consumer Data Research Centre. This body selected various criteria and applied them to towns and villages across the country. These criteria included access to health services - mainly GPs and dentists - air/environmental quality, green spaces, amenities and leisure facilities. With its Butterybank community woodland, park and blue spaces like the Burn, Coupar Angus did well in this analysis. If you are fit and healthy you may be gratified by this result. If however you are less fortunate, this particular league table will have less appeal. But it is salutary to learn that your home town has many advantages. -

GREENBURNS FARMHOUSE and STEADINGS Kettins • Blairgowrie • Perthshire • PH13 9HA

GREENBURNS FARMHOUSE AND STEADINGS Kettins • Blairgowrie • Perthshire • Ph13 9HA GREENBURNS FARMHOUSE AND STEADINGS Kettins • Blairgowrie • Perthshire • Ph13 9HA A traditional farmhouse with substantial stone steadings and paddocks For sale as a whole or in 3 lots Perth 14 miles, Dundee 14 miles, Blairgowrie 6 miles, Coupar Angus 3 miles (all distances are approximate) LOT 1 – GREENBURNS FARMHOUSE 3-4 reception rooms • 3 bedrooms • Enclosed garden and paddock Stone cart shed, kennel and fuel store About 0.89 acres EPC Rating = E LOT 2 – NORTHERN STEADING AND PADDOCK Traditional stone barns (approx 441 sqm / 4748 sqft) Steel framed hay barn • Paddock About 0.72 acres LOT 3 – EASTERN STEADING AND PADDOCK Traditional stone byres and stores (approx. 943 sqm / 10149 sqft) About 0.74 acres In all about 2.35 acres Savills Perth Solicitors Earn House, Broxden Business Park Murray Beith Murray Lamberkine Drive, Perth PH1 1RA 1-3 Glenfinlas Street [email protected] EH3 6AQ Tel: 01738 445588 Tel: 0131 225 1200 VIEWING Strictly by appointment with Savills – 01738 477525. DIRECTIONS From Coupar Angus take the Dundee road (A923) heading south. After about 0.6 miles turn left towards Ardler. The entrance to Greenburns Farm is on the left hand side after about half a mile. SITUATION Greenburns Farmhouse is surrounded by some of Perthshire’s most fertile farmland and has lovely open views across the countryside. While offering a peaceful rural lifestyle, it is only about 1 mile from Kettins village, 3 miles from the centre of Coupar Angus and about 14 miles from both Perth and Dundee. Kettins has a popular primary school and village amenities include a football pitch. -

Uniquely Perthshire Experiences Ideas with a Luxurious Edge

Uniquely Perthshire Experiences GWT Scottish Game Fair Scone Estate Fonab Castle, Pitlochry Guardswell Farm Ideas with a luxurious edge Perthshire offers many unique and luxurious experiences: whether you are looking to restore that feeling of balance and wellbeing by indulging in the finest locally-sourced food and drink, enjoy the best of the great outdoors, or want to try out a new pastime. At 119 miles, the River Tay is not only the longest river in Scotland, but also one of our five best salmon rivers. Where better then to learn to fly fish? You can even have your catch smoked locally, at the Dunkeld Smokery! You can experience the thrill of flying a Harris Hawk, ride horses through Big Tree Country, or indulge the thrill of the races. It’s all on offer in this stunning area of outstanding natural beauty. If your clients prefer indoor treats there are five-star restaurants serving up the best of our local produce; a chocolate tour; a scent-sational gin experience – as well as the award-winning Famous Grouse Experience. Year-round there are festivals, cultural attractions and serene luxury spas in which to immerse yourself. So, whether you plan to visit for the weekend, or linger for the week, there’s no shortage of unique Perthshire experiences to enjoy. BY CAR BY RAIL Aberdeen 108 99 Dundee 25 21 Edinburgh 55 65 Glasgow 58 59 Inverness 136 120 DRIVING TIME FROM PERTH (MINUTES): Stirling 35 28 For more ideas and contacts go to www.visitscotlandtraveltrade.com or email [email protected] Uniquely Perthshire Experiences Country Sport Experiences 1 2 3 4 5 Gleneagles Hotel & Estate – The Scone Palace & Estate – The Dunkeld House Hotel & Estate – Fonab House Hotel & Spa – A Atholl Estates – Enjoy a guided hotel’s 850-acre estate epitomises famous River Tay is one of Scotland’s Dunkeld House Hotel offers the truly special, luxury 5-Star Scottish trek into the heather-covered hills the natural beauty for which most celbrated salmon rivers. -

The Military Road from Braemar to the Spittal Of

E MILITARTH Y ROAD FROM BRAEMA E SPITTATH O RT L OF GLEN SHEE by ANGUS GRAHAM, F.S.A.SCOT. THAT the highway from Blairgowrie to Braemar (A 93) follows the line of an old military roa mattea s di commof o r n knowledge, thoug wore hth ofteks i n attributed, wrongly, to Wade; but its remains do not seem to have been studied in detail on FIG. i. The route from Braemar to the Spittal of Glen Shee. Highway A 93 is shown as an interrupted line, and ground above the ajoo-foot contour is dotted the ground, while published notes on it are meagre and difficult to find.1 The present paper is accordingly designed to fill out the story of the sixteen miles between BraemaSpittae th Glef d o l an rn Shee (fig. i). Glen Cluni Gled ean n Beag, wit Cairnwele hth l Pass between them,2 havo en outlinn a histors r it f Fraser1e eFo o yse Ol. e M.G ,d Th , Deeside Road (1921) ff9 . 20 , O.Se Se 2. Aberdeenshiref 6-inco p hma , and edn. (1901), sheets xcvm, cvi, cxi, surveye 186n di d 6an revised in 1900; ditto Perthshire, 2nd edn. (1901), sheets vin SW., xiv SE., xv SW., xv NW. and NE., xxm NE., surveye 186n di revised 2an 1898n deditioi e Th . Nationan no l Grid line t (1964s ye doe t )sno include this area, and six-figure references are consequently taken from the O.S. 1-inch map, yth series, sheet 41 (Braemar)loo-kmn i e ar l . -

Wildman Global Limited for Themselves and for the Vendor(S) Or Lessor(S) of This Property Whose Agents They Are, Give Notice That: 1

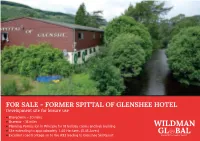

FOR SALE - FORMER SPITTAL OF GLENSHEE HOTEL Development site for leisure use ◆ Blairgowrie – 20 miles ◆ Braemar – 15 miles ◆ Planning Permission in Principle for 18 holiday cabins and hub building WILDMAN ◆ Site extending to approximately 1.40 Hectares (3.45 Acres) GL BAL ◆ Excellent road frontage on to the A93 leading to Glenshee Ski Resort PROPERTY CONSULTANT S LOCATION ACCOMMODATION VIEWING The Spittal of Glenshee lies at the head of Glenshee in the The subjects extend to an approximate area of 1.40 Hectares Strictly by appointment with the sole selling agents. highlands of eastern Perth and Kinross, Scotland. The village has (3.45 Acres). The site plan below illustrates the approximate become a centre for travel, tourism and winter sports in the region. site boundary. SITE CLEARANCE The subjects are directly located off the A93 Trunk Road which The remaining buildings and debris will be removed from the site by leads from Blairgowrie north past the Spittal to the Glenshee Ski PLANNING the date of entry. Centre and on to Braemar. The subjects are sold with the benefit of Planning Permission in Principle (PPiP) from Perth & Kinross Council to develop the entire SERVICES The village also provides a stopping place on the Cateran Trail site to provide 18 holiday cabins, a hub building and associated car ◆ Mains electricity waymarked long distance footpath which provides a 64-mile (103 parking. ◆ Mains water km) circuit in the glens of Perthshire and Angus. ◆ Further information with regard to the planning consent is available Private drainage DESCRIPTION to view on the Perth & Kinross website. -

Notices and Proceedings

THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER FOR THE SCOTTISH TRAFFIC AREA NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2005 PUBLICATION DATE: 15 April 2013 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 06 May 2013 Correspondence should be addressed to: Scottish Traffic Area Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 29/04/2013 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS Important Information All correspondence relating to bus registrations and public inquiries should be sent to: Scottish Traffic Area Level 6 The Stamp Office 10 Waterloo Place Edinburgh EH1 3EG The public counter in Edinburgh is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday to Friday. Please note that only payments for bus registration applications can be made at this counter. The telephone number for bus registration enquiries is 0131 200 4927. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede sections where appropriate. Accuracy of publication – Details published of applications and requests reflect information provided by applicants. -

Clan Macthomas Society

Clan MacTHOMAS Society Modern Ancient CREST: A demi-cat-a-mountain rampant guardant Proper, grasping in his dexter paw a serpent Vert, langued Gules, its tail environing the sinister paw MOTTO: Deo Juvante Invidiam Superabo, With God's help I will overcome envy SEPTS: Combie, MacOmie, MacOmish, McColm, McComas, McComb, McCombe, McCombie, McComie, McComish, Tam, Thom, Thomas, Thoms, Thomson A Short History: Thomas, a Gaelic speaking Highlander, known as Tomaidh Mor ('Great Tommy'), was a descendant of the Clan Chattan Mackintoshes, Thomas lived in the 15th century, at a time when the Clan Chattan Confederation had become large and unmanageable and so he took his kinsmen and followers across the Grampians, from Badenoch to Glenshee where they settled and flourished, being known as McComie (phonetic form of the Gaelic MacThomaidh), McColm and McComas (from MacThom and MacThomas). To the Government in Edinburgh, they were known as MacThomas and are so described in the Roll of the Clans in the Acts of the Scottish Parliament of 1587 and 1595 and MacThomas remains the official name of the Clan to this day. The early chiefs of the Clan MacThomas were seated at the Thom, on the east bank of the Shee Water opposite the Spittal of Glenshee. In about 1600, when the 4th Chief, Robert MacThomaidh of the Thom was murdered, the chiefship passed to his brother, John McComie of Finegand, about three miles down the Glen, which became the seat of the chiefs. By now, the MacThomases had acquired a lot of property in the glen and houses were well established at Kerrow and Benzian with shielings up Glen Beag.