THE GHOSTWAY for Margaret Mary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zed) Road, Arm Aitor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 V,: "he dreamed of dancing with the blue faced people ..." (Hosteen Klah in Paris 1990: 178; photograph by Edward S. Curtis, courtesy of Beautyway). THE YÉ’II BICHEII DANCING OF NIGHTWAY: AN EXAMINATION OF THE ROLE OF DANCE IN A NAVAJO HEALING CEREMONY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sandra Toni Francis, R.N., B.A., M. -

Navajo Mysteries and Culture

NAVAJO MYSTERIES AND CULTURE THE FOUR CORNERS WITH TONY HILLERMAN [email protected] Abstract Read the Jim Chee/Joe Leaphorn mystery novels of Tony Hillerman, augmented by the recent additions by his daughter Anne, and study the Indian myths and cultural concepts they embody. The land is sacred to the Navajo, as reflected in their religion, arts, and weaving. While enjoying Mr. Hillerman’s descriptions of southwestern landscapes and its people, review Navajo mythology with its beautiful descriptions of the cycle of life, the formation of the world, and the special reverence for land. Consider the relation of the Navajo to the Hopi and Pueblo peoples of the Anasazi migration. The course will provide an appreciation of Navajo concepts including “hozho,” going in beauty and harmony with nature, and its reversal of witchcraft (“skinwalkers”). It will delve into the basis of tribal sovereignty and existing treaties to better understand the politics of cultural preservation. The course will also consider current Navajo issues, including the control and exploitation of mineral and energy resources and their impact on the Navajo Nation. Mr. Hillerman generally weaves current issues of importance to Indian Country into his work. This is a two-semester course in which the student should expect to read about 7 first class mystery novels each semester. Course Operation While reading and enjoying the Tony Hillerman mysteries, we will discuss the examples of Navajo religion, spirituality and culture portrayed in the stories. As the opportunity arises, we’ll consider the treaties, U.S. policies, social experiments, and laws that have shaped our relations with the Navajo Nation (as well as those with all 562 federally recognized U.S. -

Mystery Readers Group

These are the books listed for Charles Todd's Ian Mystery Readers Group Rutledge series: 1996 - A Test of Wills 1998 - Wings of Fire 1999 - Search in the Dark March 28, 2002 2000 - Legacy of the Dead 2001 - Watchers of Time Here is a list of upcoming meetings, so you can mark your calendar: These are the books in Deborah Crombie's Kincaid and James series: April 16 - Murder on the Orient Express May 14 - Search the Dark - Charles Todd 1993 - A Share in Death June 11 - Kissed a Sad Goodbye - 1994 - All Shall Be Wel ***Deborah Crombie 1995 - Leave the Grave Green July 9 - Sacred Clowns - Tony Hillerman 1996 - Mourn Not Your Dead August 6 - will be announced at the next meeting 1997 - Dreaming Of the Bones September 3 or 10 - The Withdrawing 1998 - Kissed a Sad Goodbye **Room - Charlotte MacLeod 2001 - A Finer End We have several new members, as those who made the last two meetings know. Michelle and David Larsen Tony Hillerman has an impressive list: have joined us and Elva Doyen attended her first (L = Joe Leaphorn/ C = Jim Chee) meeting this month. 1970 - A Fly On the Wall (non-series) 1970 - The Blessing Way (L) 1973 - Dance Hall of the Dead (L) 1973 - Great Taos Bank Robbery Seven people made it to the Library for the March 19th **(ss and articles) meeting. The book, The Face of a Stranger, was a hit 1978 - Listening Woman (L) with us all. Various reasons were given, but all enjoyed 1980 - People of Darkness (C) the accurate Victorian atmosphere. -

UNHOLY MYSTERIES Gere Book Talk 4-11-2011 Presenter – Pam B

UNHOLY MYSTERIES Gere Book Talk 4-11-2011 Presenter – Pam B. Chesterton, G.K., 1874-1936 Dance Hall of the Head “Father Brown” England early 20th century Listening Woman Father Brown omnibus Ghostway Scandal of Father Brown People of Darkness Secret of Father Brown Skinwalkers Thief of Time Coel, Margaret, 1937- Talking God “Father John O’Malley” contemporary Wyoming Coyote Waits Eagle Catcher Sacred Clowns Ghost Walker Fallen Man Story Teller First Eagle Lost Bird Hunting Badger Spirit Woman Wailing Wind Thunder Keeper Sinister Pig Shadow Dancer Skeleton Man Killing Raven Shape Shifter Wife of Moon Eye of the Wolf Kemelman, Harry, 1908-1996 Drowning Man “Rabbi David Small” contemporary Girl With Braided Hair Friday the Rabbi slept late Silent Spirit Saturday the Rabbi went hungry Spider’s Web Sunday the Rabbi stayed home Weekend With the Rabbi Eco, Umberto Monday the Rabbi Took Off Name of the Rose Tuesday the Rabbi Saw Red Wednesday the Rabbi Got Wet Frazer, Margaret Thursday the Rabbi Walked Out “Sister Frevisse” medieval England Someday the Rabbi Will Leave Novice’s Tale One Fine Day the Rabbi Bought a Cross Outlaw’s Tale The Day the Rabbi Resigned Prioress’ Tale That Day the Rabbi Left Town Servant’s Tale Bishop’s Tale McInery, Ralph, 1929-2010 Murderer’s Tale “Father Dowling” contemporary Maiden’s Tale Seventh Station Reeve’s Tale Her Death of Cold Squire’s Tale Bishop as Pawn Clerk’s Tale Living Three Bastard’s Tale Second Vespers Hunter’s Tale Thicker Than Water Sempster’s Tale Loss of Patients Traitor’s Tale Grass Widow Apostate’s -

Read Book Skinwalkers 1St Edition

SKINWALKERS 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tony Hillerman | 9780061796715 | | | | | Skinwalkers 1st edition PDF Book For example: Comanche tend to be tall, muscular and golden skinned. Many are cruel and brutal, and this one has a name befitting its ability. Seller Inventory x Other Enid Blyton Books. Condition: UsedAcceptable. It should be noted that most of these beings are not actually gods. Unable to get into the yard, the "men" began to chant. Breen and Ed Gorman, containing the short story by Tony This edition was published in by Victor By the time the family reached Kayenta for gas, they had finally calmed down. Language: English. By using LiveAbout, you accept our. Shows minor wear, light foxing on the edges. Sponsored Listings. External Sites. This is the seventh book in Hillerman's Navajo Mystery Age Level see all. However, the medicine man can use their powers for evil. View: Gallery View. Hidden categories: Wikipedia pages semi-protected against vandalism Articles containing Navajo-language text. Their bestial forms strengthen their bodies in various ways. Skinwalkers 1st edition Writer Back to School Picks. Complete Divine. People do weird stuff when they are driving, her father replied. That was possible, but it just didn't make sense to Frances. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Seller Inventory mon Rio Grande [University of Texas Press, hardcover compilation, ] This is the full and detailed view of the first edition of Rio Grande , edited by Jan Reid, which contains, Published in by Frances's family had moved from Wyoming to Flagstaff, Arizona in shortly after her high school graduation. -

Cinemeducation Movies Have Long Been Utilized to Highlight Varied

Cinemeducation Movies have long been utilized to highlight varied areas in the field of psychiatry, including the role of the psychiatrist, issues in medical ethics, and the stigma toward people with mental illness. Furthermore, courses designed to teach psychopathology to trainees have traditionally used examples from art and literature to emphasize major teaching points. The integration of creative methods to teach psychiatry residents is essential as course directors are met with the challenge of captivating trainees with increasing demands on time and resources. Teachers must continue to strive to create learning environments that give residents opportunities to apply, analyze, synthesize, and evaluate information (1). To reach this goal, the use of film for teaching may have advantages over traditional didactics. Films are efficient, as they present a controlled patient scenario that can be used repeatedly from year to year. Psychiatry residency curricula that have incorporated viewing contemporary films were found to be useful and enjoyable pertaining to the field of psychiatry in general (2) as well as specific issues within psychiatry, such as acculturation (3). The construction of a formal movie club has also been shown to be a novel way to teach psychiatry residents various aspects of psychiatry (4). Introducing REDRUMTM Building on Kalra et al. (4), we created REDRUMTM (Reviewing [Mental] Disorders with a Reverent Understanding of the Macabre), a Psychopathology curriculum for PGY-1 and -2 residents at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. REDRUMTM teaches topics in mental illnesses by use of the horror genre. We chose this genre in part because of its immense popularity; the tropes that are portrayed resonate with people at an unconscious level. -

Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs Vol.4: S - Z

Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs vol.4: S - Z © Neuss / Germany: Bruno Buike 2017 Buike Music and Science [email protected] BBWV E30 Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs - vol.4: S - Z Neuss: Bruno Buike 2017 CONTENT Vol. 1 A-D 273 p. Vol. 2 E-K 271 p. Vol. 3 L-R 263 p. Vol. 4 S-Z 239 p. Appr. 21.000 title entries - total 1046 p. ---xxx--- 1. Dies ist ein wissenschaftliches Projekt ohne kommerzielle Interessen. 2. Wer finanzielle Forderungen gegen dieses Projekt erhebt, dessen Beitrag und Name werden in der nächsten Auflage gelöscht. 3. Das Projekt wurde gefördert von der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Sozialamt Neuss. 4. Rechtschreibfehler zu unterlassen, konnte ich meinem Computer trotz jahrelanger Versuche nicht beibringen. Im Gegenteil: Das Biest fügt immer wieder neue Fehler ein, wo vorher keine waren! 1. This is a scientific project without commercial interests, that is not in bookstores, but free in Internet. 2. Financial and legal claims against this project, will result in the contribution and the name of contributor in the next edition canceled. 3. This project has been sponsored by the Federal Republic of Germany, Department for Social Benefits, city of Neuss. 4. Correct spelling and orthography is subject of a constant fight between me and my computer – AND THE SOFTWARE in use – and normally the other side is the winning party! Editor`s note – Vorwort des Herausgebers preface 1 ENGLISH SHORT PREFACE „Paul Smith“ is a FAKE-IDENTY behind which very probably is a COLLCETIVE of writers and researchers, using a more RATIONAL and SOBER approach towards the complex of Rennes-le-Chateau and to related complex of „Priory of Sion“ (Prieure de Sion of Pierre Plantard, Geradrd de Sede, Phlippe de Cherisey, Jean-Luc Chaumeil and others). -

Literariness.Org-Michael-Cook-Auth

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fiction has never been more popular. In novels, short stories, films, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fiction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fiction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial inves- tigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehen- sive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Published titles include : Maurizio Ascari A COUNTER-HISTORY OF CRIME FICTION Supernatural, Gothic, Sensational Pamela Bedore DIME NOVELS AND THE ROOTS OF AMERICAN DETECTIVE FICTION Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Ed Christian ( editor ) THE POST-COLONIAL DETECTIVE Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Michael Cook NARRATIVES OF ENCLOSURE IN DETECTIVE FICTION The Locked Room Mystery Michael Cook DETECTIVE FICTION AND THE GHOST STORY The Haunted Text Barry Forshaw DEATH IN A COLD CLIMATE A Guide to Scandinavian Crime Fiction Barry Forshaw BRITISH CRIME FILM Subverting -

Latta Rebuts Congressman?S Charges by JANE FODERARO FT

County Seeking $700,000 in Federal Road Aid SEE STORY BELOW Warm, Humid THEIMI FINAL Sunny, warm and humid to- day. Clear and mild tonight. Red Bonk, Freehold Sunny and hot tomorrow. I Long- Branch 7 EDITION (See Details. P«so 3), Monmouth County's Home Newspaper for 90 Years VOt. .91, NO. 246 RED BANK, N. J., THURSDAY, JUNE 12, 1969 36 PAGES 10 CENTS rjri.ni [MFT^IHIII [JII IMI nJMLiiiiJJuiiiiiiiiiiiiiuiniiM! iiirN?n-r:?? iJiEUMiuiiHEL jiinrjuiuiiUi ii'i mi iiirii'i^iiMMiiiNiii mi MfMiUiini !Ji:irnii;n r:u iiihih<niMiiiiiiitMi]j.jjiri:;.'i.ir!i::j-:* Latta Rebuts Congressman?s Charges By JANE FODERARO FT. MONMOUTH - Maj. Gen. William B. Latta set out yesterday to "set the record straight." Armed with charts, drawings, regulations, statistics and drive, the commander oi the Electronics Command unleashed a barrage oi facts to rebut charges that the Army wastes money. In a four-hour press conference, Gen. Latta did not ad- dress himself to Ms Washington critic, Rep. William H. Harsha, E-Ohio. Rather, he conducted a scrupulous review of the criticism. The congressman for a month has delivered emotionally charged floor statements attacking ECOM, leading up to to- day's introduction of his legislation on military procurements. Citing five case histories of alleged over-spending at Ft. Mon- month, Rep. Harsha also targeted Gen. Latta. (The congress- man says he seeks "to determine aiid expose the real in- dividual source of the problem" then immediately adds, "I do know, for example, that the commanding general of the Army Electronics Command is Maj. -

Western Touring Photo Album

Tschanz Rare Books Denver Book Fair List 24 Usual terms. Items Subject to prior sale. Call: 801-641-2874 Or email: [email protected] to confirm availability. Domestic shipping: $10 International and overnight shipping billed at cost. www.tschanzrarebooks.com Ludlow Massacre and Colorado Coalfield War 1- Dold, Louis R. 29 Real Photo Postcards on the Ludlow Massacre and the Colorado Coalfield War. [Trinidad, CO]: L.R. Dold Photo, 1913-1914. 29 RPPC [8.5 cm x 14 cm] all are very good or better with only four having contemporary (1913-1914)manuscript notes and postmarks from Trinidad, Colorado. All have detailed identifications in pencil, by noted Colorado post card collector, Charles A. Harbert. Lou Dold's excellent photographs show the places and people surrounding the Ludlow Massacre and the destruction that would take place in its wake, and would be featured in newspapers and periodicals around the world. "That winter Lou Dold had been making good money selling postcards of the strike. He sold them like newspapers just as soon as he made them." - Zeese Papanikolas 'Buried Unsung' p.185 The Ludlow Massacre was preceded by a strike of 1200 miners in September of 1913, who were striking against the unsafe and unjust treatment of John D. Rockefeller's Colorado Fuel and Iron Company. The striking miner's were evicted from their company owned homes and soon relocated to a tent city north of Trinidad, that was erected by the United Mine Workers of America. Rhetoric and violence escalated between the striking miners and the mine companies and the (largely immigrant) strikebreaking miners that were brought in to replace them. -

Item More Personal, More Unique, And, Therefore More Representative of the Experience of the Book Itself

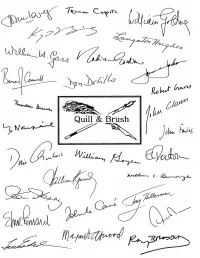

Q&B Quill & Brush (301) 874-3200 Fax: (301)874-0824 E-mail: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.qbbooks.com A dear friend of ours, who is herself an author, once asked, “But why do these people want me to sign their books?” I didn’t have a ready answer, but have reflected on the question ever since. Why Signed Books? Reading is pure pleasure, and we tend to develop affection for the people who bring us such pleasure. Even when we discuss books for a living, or in a book club, or with our spouses or co- workers, reading is still a very personal, solo pursuit. For most collectors, a signature in a book is one way to make a mass-produced item more personal, more unique, and, therefore more representative of the experience of the book itself. Few of us have the opportunity to meet the authors we love face-to-face, but a book signed by an author is often the next best thing—it brings us that much closer to the author, proof positive that they have held it in their own hands. Of course, for others, there is a cost analysis, a running thought-process that goes something like this: “If I’m going to invest in a book, I might as well buy a first edition, and if I’m going to invest in a first edition, I might as well buy a signed copy.” In other words we want the best possible copy—if nothing else, it is at least one way to hedge the bet that the book will go up in value, or, nowadays, retain its value. -

Book Club at the Museum Discussion Guide for a Thief of Time by Tony Hillerman

Book Club at the Museum Discussion Guide for A Thief of Time by Tony Hillerman 2013-2014 Utah Museum of Fine Arts Book Club Selection Use the information and discussion guide on the following pages to facilitate your book club’s conversation of this book. Then, visit us at www.umfa.utah.edu/bookclub to schedule your tour. 1. How does Hillerman’s description of the American Southwest landscape enhance the reader’s understanding of the physical and cultural geography of the Navajo people? 2. Popular culture often presents preconceived ideas about the American West as a romantic frontier and a place where the American dream is fulfilled. How does Tony Hillerman paint the West in his novels? 3. Hillerman is not an American Indian; however, his portrayal of American Indian culture is central to his novels. Do you think a writer of culturally specific literature needs to be a member of that culture? Why or why not? 4. Hillerman includes elements of American Indian spirituality in his novels. How does spirituality drive the action of the characters in this story? 5. Leaphorn’s wife, Emma, has recently died. Hillerman devotes many paragraphs to Leaphorn’s “ghost sickness,” a concept that Leaphorn had previously regarded as superstitious. How do Leaphorn’s religious beliefs change throughout the novel? 6. Hillerman highlights some ceremonial Navajo rituals in his novel. What role do these rituals play in the story and in the lives of the characters? 7. What is more interesting to you as a reader: the case the detectives investigate, or the life and culture of the American Indian detective? 8.