Vocal Learning in Grey Parrots (Psittacus Erithacus): Effects of Social Interaction, Reference, and Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Species Reviewed Under Resolution Conf

AC17 Inf. 3 (English only/ Solamente en inglés/ Seulement en anglais) HISTORY OF SPECIES REVIEWED UNDER RESOLUTION CONF. 8.9 (Rev.) PART 1: AVES Species Survival Network 2100 L Street NW Washington, DC 20037 July 2001 AC17 Inf. 3 – p. 1 SIGNIFICANT TRADE REVIEW: PHASE 1 NR = none reported Agapornis canus: Madagascar Madagascar established an annual export quota of 3,500 in 1993, pending the results of a survey of the species in the wild (CITES Notification No. 744). Year 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 Quota 3500 3500 3500 3500 3500 3500 3500 3200 Exports 4614 5495 5270 3500 6200 • Export quota exceeded in 1994, 1995, 1996 and 1998. From 1994 - 1998, export quota exceeded by a total of 7,579 specimens. • Field project completed in 2000: R. J. Dowsett. Le statut des Perroquets vasa et noir Coracopsis vasa et C. nigra et de l’Inséparable à tête grise Agapornis canus à Madagascar. IUCN. Agapornis fischeri: Tanzania Trade suspended in April 1993 (CITES Notification No. 737). Year 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 Quota NR NR NR NR NR NR Exports 300 0 0 2 0 • Field project completed in 1995: Moyer, D. The Status of Fischer’s Lovebird Agapornis fischeri in the United Republic of Tanzania. IUCN. • Agapornis fischeri is classified a Lower Risk/Near Threatened by the IUCN. Amazona aestiva: Argentina 1992 status survey underway. Moratorium on exports 1996 preliminary survey results received quota of 600. Year 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 Chick Quota 1036 2480 3150 Juvenile Quota 624 820 1050 Total Quota NR 600 NR 1000 Exports 19 24 130 188 765 AC17 Inf. -

African Grey Parrots

African Grey Parrots African Grey Parrot Information The African Grey Parrot, Psittacus erithacus , is a medium-sized parrot native to the primary and secondary rainforests of West and Central Africa. Its mild temperament, clever mind and ability to mimic sounds, including human speech, has made it a highly sought after pet for many centuries. Certain individuals also have a documented ability to understand the meaning of words. African Grey Parrots Taxonomy Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Aves Order: Psittaciformes Family: Psittacidae Tribe: Psittacini Genus: Psittacus Species: Psittacus erithacus The African Grey Parrot is the only recognized species of the genus Psittacus. The genus name “Psittacus” is derived from the word ψιττακος (psittakos ) which means parrot in Ancient Greek. There are two recognized subspecies of African Grey Parrot ( Psittacus erithacus) : 1. Congo African Grey Parrot ( Psittacus erithacus erithacus ) 2. Timneh African Grey Parrot ( Psittacus erithacus timneh ) Congo African Grey Parrot ( Psittacus erithacus erithacus ), commonly referred to as “CAG” by parrot keepers, is larger than the Timneh African Grey Parrot and normally reaches a length of roughly 33 cm. It is found from the south-eastern Ivory Coast to Western Kenya, Northwest Tanzania, Southern Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Northern Angola, including the islands of Príncipe and Bioko in the Gulf of Guinea. Adult members of this subspecies are light grey with red tails, pale yellow irises, and an all black beak. Pet Congo African Grey Parrots usually learn to speak quite slowly until their second or third year. Timneh African Grey Parrot ( Psittacus erithacus timneh ), commonly referred to as “TAG” by parrot keepers, is smaller than the Congo subspecies and is endemic to the to the western parts of the moist Upper Guinea forests and nearby West African savannas from Guinea-Bissau, Sierra Leone and Southern Mali to at least 70 km east of the Bandama River in Côte d’Ivoire. -

Poicephalus Senegalus Linnaeus, 1766

AC22 Doc. 10.2 Annex 2 Poicephalus senegalus Linnaeus, 1766 FAMILY: Psittacidae COMMON NAMES: Senegal Parrot (English); Perroquet à Tête Grise, Perroquet Youyou, Youyou (French); Lorito Senegalés, Papagayo Senegalés (Spanish). GLOBAL CONSERVATION STATUS: Listed as Least Concern A1bcd in the 2004 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN, 2004). SIGNIFICANT TRADE REVIEW FOR: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Togo Range States selected for review Range State Exports* Urgent, Comments possible or least concern Benin 0Least concern No exports reported. Burkina Faso 13Least concern Exports minimal. Cameroon 1,687Least concern Significant exports only recorded in 1997 and 1998 Chad 0Least concern No exports reported. Côte d’Ivoire 1,193Least concern Significant exports only recorded in 2002 and 2003; if exports increase further information would be required to support non-detriment findings Gambia 12Least concern Exports minimal. Ghana 1Least concern Exports minimal. Guinea 164,817Possible Exports have declined since 1998, but remain significant. Further information concern required to confirm non-detrimental nature of exports. Guinea- 132Least concern Exports minimal. Bissau Liberia 4,860Possible Not believed to be a range country for this species but significant exports concern reported 1999-2003 whose origin should be clarified Mali 60,742Possible Exports have increased significantly since 2000. Status of the species is poorly concern known; no systematic population monitoring. Mauritania 0Least concern No exports reported. Niger 0Least concern No exports reported. Nigeria 301Least concern Exports minimal. Senegal 173,794Possible Consistently exported high numbers since 1982; species apparently remains concern common but no population monitoring known to be in place Sierra Leone 0Least concern No exports reported. -

USE of SUB-SAHARAN VULTURES in TRADITIONAL MEDICINE and CONSERVATION and POLICY ISSUES for the AFRICAN GREY PARROT (Psittacus Er

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 12-2010 USE OF SUB-SAHARAN VULTURES IN TRADITIONAL MEDICINE AND CONSERVATION AND POLICY ISSUES FOR THE AFRICAN GREY PARROT (Psittacus erithacus) Kristina Dunn Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Dunn, Kristina, "USE OF SUB-SAHARAN VULTURES IN TRADITIONAL MEDICINE AND CONSERVATION AND POLICY ISSUES FOR THE AFRICAN GREY PARROT (Psittacus erithacus)" (2010). All Theses. 1036. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1036 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. USE OF SUB-SAHARAN VULTURES IN TRADITIONAL MEDICINE AND CONSERVATION AND POLICY ISSUES FOR THE AFRICAN GREY PARROT ( Psittacus erithacus ) A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Wildlife and Fisheries Biology by Kristina Michele Dunn December 2010 Accepted by: Dr. William W. Bowerman, Committee Chair Dr. Karen C. Hall Dr. Webb M. Smathers Jr. ABSTRACT Wildlife populations worldwide are being negatively affected by the illegal wildlife trade. The severity of the impact to both Sub-Saharan vultures and African Grey Parrot (Psittacus erithacus ) (AGP) populations are explored in this thesis. Many species of Sub-Saharan vultures are used in the traditional medicinal trade. Previous studies have found that vultures have mystical powers attributed to them due to their keen ability to find food. -

Acquisition of the Same/Different Concept by an African Grey Parrot (Psittacus Erithacus): Learning with Respect to Categories of Color, Shape, and Material

Animal Learning & Behavior 1987, 15 (4), 423-432 Acquisition of the same/different concept by an African Grey parrot (Psittacus erithacus): Learning with respect to categories of color, shape, and material IRENE M. PEPPERBERG Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois An African Grey parrot, previously taught to use vocal English labels to discriminate more than 80 different objects and to respond to questions concerning categorical concepts of color and shape, was trained and tested on relational concepts of same and different. The subject, Alex, replied with the correct English categorical label ("color," "shape," or "mah-mah" [matter]) when asked "What's same?" or "What's different?" about pairs of objects that varied with respect to any combination of attributes. His accuracy was 69.7%-76.6% for pairs of familiar objects not used in training and 82.3%-85% for pairs involving objects whose combinations of colors, shapes, and materials were unfamiliar. Additional trials demonstrated that his responses were based upon the question being posed as well as the attributes of the objects. These findings are dis cussed in terms of his comprehension of the categories of color, shape, and material and as evi dence of his competence in an exceptional (non-species-specific) communication code. Recent studies (Pepperberg, 1987a, 1987b) have shown ity of animals to master nonrelational concepts, several that at least one avian subject, an African Grey parrot researchers suggest that existing data on relational con (Psittacus erithacus) , can exhibit capacities once thought cepts reflect qualitative as well as quantitative species to belong exclusively to humans and, possibly, certain differences. -

Chbird 21 Previous Page, a Blue and Yellow Macaw (Ara Ararauna)

itizing Watch Dig bird Parrots in Southeast Asian Public Collections Aviculture has greatly evolved during the past 50 years, from keeping a collection of colorful birds to operating captive breeding programs to sustain trade and establish a viable captive population for threatened species. Many bird families are now fairly well represented in captivity, but parrots have a special place. Story and photography by Pierre de Chabannes AFA Watchbird 21 Previous page, a Blue and Yellow Macaw (Ara ararauna). Above, a bizarre version of a Black Lory, maybe Chalcopsitta atra insignis. hat makes parrots so attractive colorful species to be found there and the Southeast Asia, the Philippines and the four to both professional breeders, big areas of unexplored forests, both inland main Islands of western Indonesia, namely Wbirdwatchers and zoo visitors is and insular, that could provide the discov- Borneo, Sumatra, Java and Bali, along with a combination of many factors, including erer with many new bird varieties like it did their satellite islands. Here, the forests are their bright colors, their conspicuousness, recently in Papua New Guinea. mostly to be qualifi ed as tropical wet rain- their powerful voice coupled with complex Th e diversity and distribution of parrots forests with a much more humid climate behaviour that allows them to be spotted in this region follows a pattern described throughout the year and less important sea- easily in the fi eld and, most important of all, by Alfred Russel Wallace in the 19th Cen- sonal variations. their ability to interact with humans and tury with the clear separation from the Finally, Wallacea is really a transitional even “learn” new kinds of behaviours from Asian and the Australian zoogeographical zone which has characteristics of both Asian them. -

Cockatoos, Parrots and Parakeets Family PSITTACIDAE

Text extracted from Gill B.J.; Bell, B.D.; Chambers, G.K.; Medway, D.G.; Palma, R.L.; Scofield, R.P.; Tennyson, A.J.D.; Worthy, T.H. 2010. Checklist of the birds of New Zealand, Norfolk and Macquarie Islands, and the Ross Dependency, Antarctica. 4th edition. Wellington, Te Papa Press and Ornithological Society of New Zealand. Pages 249, 252-254 & 256-257. Order PSITTACIFORMES: Cockatoos, Parrots and Parakeets New molecular data and analyses support a view that the two subfamilies Strigopinae and Nestorinae form a single clade basal to all other Recent members of the order Psittaciformes (e.g. de Kloet & de Kloet 2005, Astuti et al. 2006, Tokita et al. 2007, Wright et al. 2008). They therefore need to be put in a family of their own (rather than in Psittacidae, e.g. Checklist Committee 1990) placed ahead of Cacatuidae in the systematic list. The name Strigopidae G.R. Gray, 1848 has priority. Family PSITTACIDAE: Typical Parrots Psittacini Illiger, 1811: Prodromus Syst. Mamm. Avium: 195, 200 – Type genus Psittacus Linnaeus, 1758. Subfamily PLATYCERCINAE: Rosellas and Broad-tailed Parrots Platycercine Selby, 1836: Natural History Parrots: 64 – Type genus Platycercus Vigors, 1825. Genus Cyanoramphus Bonaparte Cyanoramphus Bonaparte, 1854: Revue Mag. Zool. 6 (2nd series): 153 – Type species (by subsequent designation) Cyanoramphus zealandicus (Latham, 1790). Cyanorhamphus Sclater, 1858: Journ. Linn. Soc. London, Zoology 2: 164. Unjustified emendation. Bulleria Iredale & Mathews, 1926: Bull. Brit. Ornith. Club 46: 76 – Type species (by original designation) Platycercus unicolor Lear = Cyanoramphus unicolor (Lear). For general discussion of speciation in the genus see Taylor (1985), Boon, Daugherty et al. -

AFRICAN GREY PARROT (Psittacus Erithacus)

AFRICAN GREY PARROT (Psittacus erithacus) PROPOSAL: CoP17 Prop. 19 Gabon et al. Transfer from Appendix II to Appendix I of Psittacus erithacus in accordance with Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP16), McKelvie Annex 1. © Sherry IFAW RECOMMENDATION: SUPPORT species and their ability to learn and mimic human language has made them a target for traders. Biology and Distribution Protection Status African grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus) were historically found in large numbers in western and In 1981, CITES Parties listed the African grey parrot central Africa in moist, lowland, tropical forests. on Appendix II due to the potential impact of trade Now their population has been greatly reduced due on its population at that time. The species has been to capture for the live pet trade, habitat destruction the subject of multiple reviews of significant trade, and fragmentation. It has been estimated that the most recent being 2014. A CITES Significant Trade their population has decreased between 50-90% Review of African grey parrots in 2006 highlighted in some range states and they are locally extinct that the trade originating in three of the top eight in others. exporters of CITES-listed birds to Singapore -- African greys are highly intelligent, social birds of Guinea, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the family Psittacidae. They are known for roosting the Central African Republic -- was of possible or and congregating in large groups in search of fruit, urgent concern because of unsustainable export nuts and seeds. African greys can live up to 15.5 levels. The review of Significant Trade showed that years, however, they have a low reproductive rate. -

Proposal to Transfer African Grey Parrots (Psittacus Erithacus)

Proposal to transfer African Grey Parrots (Psittacus erithacus) from CITES Appendix II to Appendix I Proposal to transfer African Grey Parrots (Psittacus erithacus) from CITES Appendix II to Appendix I FAQ © C HARLES B ERGMAN 1 Proposal to transfer African Grey Parrots to CITES Appendix II to Appendix I 1 Do Grey parrots qualify for Appendix I listing? Yes. Marked declines in Grey parrot populations have been observed and are ongoing. These declines are driven by patterns of exploitation and decreases in habitat quality and area. In 2012 it was uplisted to Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species on the basis that “the extent of the annual harvest for international trade, in combination with the rate of ongoing habitat loss, means it is now suspected to be undergoing rapid declines over three generations (47 years)” (BirdLife International 2015). Recent accounts indicate population declines in excess of 50% over three generations (47 years) in multiple range States (Tamungang and Cheke 2012, Annorbah et al. 2016). In some areas, declines have been very severe; in Ghana, where Grey parrots were once common and widespread, populations have declined between 90 and 99% since the early 1990s (less than two generations) and there is no evidence that declines are any less severe elsewhere in West Africa (Annorbah et al. 2016). Grey parrots are locally extinct or known to occur in very low numbers in Angola, Benin, Burundi, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Nigeria, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Togo (Clemmons 2003, da Costa Lopes 2015, Martin et al. 2014a, McGowan 2001, Marsden et al. -

Nationally Threatened Species for Uganda

Nationally Threatened Species for Uganda National Red List for Uganda for the following Taxa: Mammals, Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Butterflies, Dragonflies and Vascular Plants JANUARY 2016 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research team and authors of the Uganda Redlist comprised of Sarah Prinsloo, Dr AJ Plumptre and Sam Ayebare of the Wildlife Conservation Society, together with the taxonomic specialists Dr Robert Kityo, Dr Mathias Behangana, Dr Perpetra Akite, Hamlet Mugabe, and Ben Kirunda and Dr Viola Clausnitzer. The Uganda Redlist has been a collaboration beween many individuals and institutions and these have been detailed in the relevant sections, or within the three workshop reports attached in the annexes. We would like to thank all these contributors, especially the Government of Uganda through its officers from Ugandan Wildlife Authority and National Environment Management Authority who have assisted the process. The Wildlife Conservation Society would like to make a special acknowledgement of Tullow Uganda Oil Pty, who in the face of limited biodiversity knowledge in the country, and specifically in their area of operation in the Albertine Graben, agreed to fund the research and production of the Uganda Redlist and this report on the Nationally Threatened Species of Uganda. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREAMBLE .......................................................................................................................................... 4 BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................... -

Psittacus Erithacus Linnaeus, 1758

AC22 Doc. 10.2 Annex 1 Psittacus erithacus Linnaeus, 1758 FAMILY: Psittacidae COMMON NAMES: Grey Parrot (English); Jacko, Jacquot, Perroquet Gris, Perroquet Jaco (French); Loro Yaco, Yaco (Spanish). GLOBAL CONSERVATION STATUS: Listed as: Least Concern in the 2004 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, currently under review (IUCN, 2004). SIGNIFICANT TRADE REVIEW FOR: Angola, Benin, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya; Liberia, Mali, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Togo, Uganda. Range States selected for review Range State Exports* Urgent, possible or Comments (1994-2003) least concern Angola 191 Least concern Low levels of exports reported Benin 13 Least concern Low levels of exports reported Burundi 0 Least concern No reported exports Cameroon 156,855 Urgent concern Little recent population information, however indications of localised declines and range contraction; export quotas (which have regularly been exceeded) may be high relative to sustainable offtake; suspected illegal trade a concern Central 228 Least concern Low levels of exports reported African Republic Congo 31,946 Possible concern Exports increasing in recent years; quotas regularly exceeded; little recent population information, scientific basis for quotas and non-detrimental nature of exports not clear Côte **18,903 Urgent concern Exports increasing in recent years; quotas regularly exceeded; little recent d’Ivoire population information but habitat disappearing; -

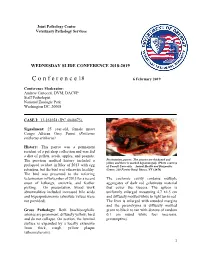

C O N F E R E N C E 18 6 February 2019

Joint Pathology Center Veterinary Pathology Services WEDNESDAY SLIDE CONFERENCE 2018-2019 C o n f e r e n c e 18 6 February 2019 Conference Moderator: Andrew Cartoceti, DVM, DACVP Staff Pathologist National Zoologic Park Washington DC, 20008 CASE I: 13-161654 (JPC 4048673). Signalment: 25 year-old, female intact Congo African Grey Parrot (Psittacus erithacus erithacus) History: This parrot was a permanent resident of a pet shop collection and was fed a diet of pellets, seeds, apples, and peanuts. The previous medical history included a Presentation, parrot: The arteries are thickened and yellow and there is marked hepatomegaly. (Photo courtesy prolapsed oviduct in May of 2013 with egg of Cornell University – Animal Health and Diagnostic retention, but the bird was otherwise healthy. Center, 240 Farrier Road, Ithaca, NY 14850) The bird was presented to the referring veterinarian in November of 2013 for a recent The coelomic cavity contains multiple onset of lethargy, anorexia, and feather aggregates of dark red gelatinous material picking. On presentation, blood work that cover the viscera. The spleen is abnormalities included increased bile acids uniformly enlarged measuring 4.7 x4.5 cm and hyperproteinemia (absolute values were and diffusely mottled white to light tan to red. not provided). The liver is enlarged with rounded margins and the parenchyma is diffusely mottled Gross Pathology: Both brachiocephalic green to black to tan with dozens of random arteries are prominent, diffusely yellow, hard 0.1 cm round white foci (necrosis, and do not collapse. On section, the luminal presumptive). surface is expanded by a locally extensive 1mm thick, rough, yellow plaque (atherosclerosis).