SGI President Ikeda's Study Lecture Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Did Glooskap Kill the Dragon on the Kennebec? Roslyn

DID GLOOSKAP KILL THE DRAGON ON THE KENNEBEC? ROSLYN STRONG Figure 1. Rubbing of the "dragon" petroglyph Figure 2. Rock in the Kennebec River, Embden, Maine The following is a revised version of a slide presentation I gave at a NEARA meeting a number of years ago. I have accumulated so many fascinating pieces of reference that the whole subject should really be in two parts, so I will focus here on the dragon legends and in a future article will dwell more on the mythology of the other petroglyphs, such as thunderbirds. This whole subject began for me at least eight years ago when George Carter wrote in his column "Before Columbus" in the Ellsworth American that only Celtic dragons had arrows on their tails. The dragon petroglyph [Fig. 1] is on a large rock [Fig. 2] projecting into the Kennebec river in the town of Embden, which is close to Solon, in central Maine. It is just downstream from the rapids, and before the water level was raised by dams, would have been a logical place to put in after a portage. The "dragon" is one of over a hundred petroglyphs which includes many diverse subjects - there are quite a few canoes, animals of various kinds, human and ‘thunderbird’ figures. They were obviously done over a long period of time since there are many layers and the early ones are fainter. They are all pecked or ‘dinted’ which is the term used by archaeologists. The styles and technique seem to be related to the petroglyphs at Peterborough, Ontario, which in turn appear to be similar to those in Bohuslan, Sweden. -

PDF Download Green Arrow a Celebration of 75 Years

GREEN ARROW A CELEBRATION OF 75 YEARS: A CELEBRATION OF 75 YEARS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Various | 500 pages | 12 Jul 2016 | DC Comics | 9781401263867 | English | United States Green Arrow a Celebration of 75 Years: A Celebration of 75 Years PDF Book We also get to see the beginning and continuing friendship of Green Lantern and Green Arrow. Use your keyboard! If you're interested in the Green Arrow's evolution, you might like this book as a primer to jump to other stories. Reviewed by:. Dan Jurgens Artist ,. Adam Peacock rated it it was amazing Feb 21, I have mixed feelings about this story. Batman knocks Ollie out to have a closer examination and see if he is the real deal. Hardcover , pages. Get A Copy. This issue was most recently modified by:. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. Green Arrow: A Celebration of 75 Years. Select Option. So many reboots and rebirths over the years make a book like this necessary so you can have an idea of what is going on. We're given the dramatic endings but I have no idea who any of these characters are or what is going on. Mike Cullen rated it really liked it Feb 16, Go to Link Unlink Change. Story Arcs. Two thousand one saw filmmaker Kevin Smith pick up torch and move the original GA into a new century. We're committed to providing low prices every day, on everything. Jan 04, Simone rated it really liked it. Release Date:. This edit will also create new pages on Comic Vine for:. -

Dragon Con Progress Report 2021 | Published by Dragon Con All Material, Unless Otherwise Noted, Is © 2021 Dragon Con, Inc

WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG INSIDE SEPT. 2 - 6, 2021 • ATLANTA, GEORGIA • WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG Announcements .......................................................................... 2 Guests ................................................................................... 4 Featured Guests .......................................................................... 4 4 FEATURED GUESTS Places to go, things to do, and Attending Pros ......................................................................... 26 people to see! Vendors ....................................................................................... 28 Special 35th Anniversary Insert .......................................... 31 Fan Tracks .................................................................................. 36 Special Events & Contests ............................................... 46 36 FAN TRACKS Art Show ................................................................................... 46 Choose your own adventure with one (or all) of our fan-run tracks. Blood Drive ................................................................................47 Comic & Pop Artist Alley ....................................................... 47 Friday Night Costume Contest ........................................... 48 Hallway Costume Contest .................................................. 48 Puppet Slam ............................................................................ 48 46 SPECIAL EVENTS Moments you won’t want to miss Masquerade Costume Contest ........................................ -

Dragon Magazine

DRAGON 1 Publisher: Mike Cook Editor-in-Chief: Kim Mohan Shorter and stronger Editorial staff: Marilyn Favaro Roger Raupp If this isnt one of the first places you Patrick L. Price turn to when a new issue comes out, you Mary Kirchoff may have already noticed that TSR, Inc. Roger Moore Vol. VIII, No. 2 August 1983 Business manager: Mary Parkinson has a new name shorter and more Office staff: Sharon Walton accurate, since TSR is more than a SPECIAL ATTRACTION Mary Cossman hobby-gaming company. The name Layout designer: Kristine L. Bartyzel change is the most immediately visible The DRAGON® magazine index . 45 Contributing editor: Ed Greenwood effect of several changes the company has Covering more than seven years National advertising representative: undergone lately. in the space of six pages Robert Dewey To the limit of this space, heres some 1409 Pebblecreek Glenview IL 60025 information about the changes, mostly Phone (312)998-6237 expressed in terms of how I think they OTHER FEATURES will affect the audience we reach. For a This issues contributing artists: specific answer to that, see the notice Clyde Caldwell Phil Foglio across the bottom of page 4: Ares maga- The ecology of the beholder . 6 Roger Raupp Mary Hanson- Jeff Easley Roberts zine and DRAGON® magazine are going The Nine Hells, Part II . 22 Dave Trampier Edward B. Wagner to stay out of each others turf from now From Malbolge through Nessus Larry Elmore on, giving the readers of each magazine more of what they read it for. Saved by the cavalry! . 56 DRAGON Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is pub- I mention that change here as an lished monthly for a subscription price of $24 per example of what has happened, some- Army in BOOT HILL® game terms year by Dragon Publishing, a division of TSR, Inc. -

Dragon Magazine

— The Magazine of Fantasy, Swords & Sorcery, and Science Fiction Game Playing— A non-wargaming friend of mine recently asked me why I did this; why did I put all my effort into this line of work? What did I perceive my endeavors to be? Part of this curiosity stems from the fact that this person has no inkling of what games are all about, in our context of gaming. He still clings to the shibboleth that wargamers are classic cases of arrested de- velopment, never having gotten out of the sandbox and toy soldiers syndrome of childhood. He couldn’t perceive the function of a magazine about game-playing. This is what I told him: Magazines exist to disseminate information. The future of magazine publishing, the newly revived LIFE and LOOK notwithstand- VOL. III, No. 11 May, 1979 ing, seems to be in specialization. Magazines dealing with camping, quilting, motorcycles, cars, dollhouse miniatures, music, teen interests, DESIGN/DESIGNERS FORUM modeling, model building, horses, dogs, fishing, hunting, guns, hairstyl- A Part of Gamma World Revisited —Jim Ward ................ 5 ing and beauty hints already exist; why not wargaming? Judging and You—Jim Ward ............................... 7 I put out TD as a forum for the exchange of gaming ideas, Sorceror’s Scroll—The Proper Place of Character philosophies, variants and debate. TD is a far cry from Soldier of For- Social Class in D&D -- Gary Gygax ........ .12 tune, that bizarre publication for mercenaries, gun freaks and other vio- 20th Century Primitive—Gary Jacquet ...................... 24 lence mongers. In fact, the greater part of wargamers are quite pacifistic Gamma World Artifact Use Chart —Gary Jacquet ............ -

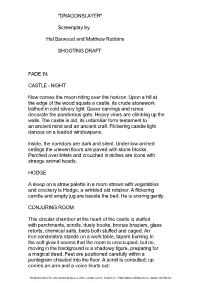

"DRAGONSLAYER" Screenplay by Hal Barwood and Matthew Robbins SHOOTING DRAFT FADE IN: CASTLE

"DRAGONSLAYER" Screenplay by Hal Barwood and Matthew Robbins SHOOTING DRAFT FADE IN: CASTLE - NIGHT Now comes the moon riding over the horizon. Upon a hill at the edge of the wood squats a castle, its crude stonework bathed in cold silvery light. Queer carvings and runes decorate the ponderous gate. Heavy vines are climbing up the walls. The castle is old, its unfamiliar form testament to an ancient mind and an ancient craft. Flickering candle light dances on a leaded windowpane. Inside, the corridors are dark and silent. Under low arched ceilings the uneven floors are paved with stone blocks. Perched over lintels and crouched in niches are icons with strange animal heads. HODGE A sleep on a straw palette in a room strewn with vegetables and crockery is Hodge, a wrinkled old retainer. A flickering candle and empty jug are beside the bed. He is snoring gently. CONJURING ROOM This circular chamber at the heart of the castle is stuffed with parchments, scrolls, dusty books, bronze braziers, glass retorts, chemical salts, birds both stuffed and caged. An iron candelabra stands on a work table, tapers burning. In the soft glow it seems that the room is unoccupied, but no, moving in the background is a shadowy figure, preparing for a magical deed. Feet are positioned carefully within a pentagram chiseled into the floor. A scroll is consulted; up comes an arm and a voice blurts out: Script provided for educational purposes. More scripts can be found here: http://www.sellingyourscreenplay.com/library VOICE Omnia in duos: Duo in Unum: Unus in Nihil: Haec nec Quattuor nec Omnia nec Duo nec Unus nec Nihil Sunt. -

Dragon Magazine

— The Magazine of Fantasy, Swords & Sorcery, and Science Fiction Game Playing — This issue marks the beginning of the new assistant editor’s tenure, and his touch is already evident. I won’t detail his innovations, nor will I detail which are mine; This new combined format is a combined effort. Other than various ad- ministrative duties, the only division of labor that we practice is that I tend to read and validate the historical pieces, as my background in history is more extensive than his. At the end of this piece, I have asked Jake to write a little introductory bit to give you, the readers, an idea of both where he is coming from, and what you can expect from him. His joining the magazine has already been advantageous. As can be expected with any infusion of new ideas, we already have dozens of plots and schemes simmering away, all designed to improve the quality of the magazine and to sell more copies of it. Vol. III, No. 12 June, 1979 This issue marks the introduction, or re-introduction in some cases, of some FEATURES different components of the magazine. We have returned the old FEATURED CREATURE, having renamed the column THE DRAGON’S BESTIARY. This System 7 Napoleonics — system analysis . 4 will now become a regular monthly feature. If you note this month’s entry care- Giants in the Earth — fictitious heros . 13 fully, you will note a new authenticity. GIANTS IN THE EARTH is another new D&D, AD&D, and Gaming — Sorcerer’s Scroll . 28 entry, designed to add some spice to your D&D or AD&D campaign. -

Dragon Magazine #236

The dying game y first PC was a fighter named Random. I had just read “Let’s go!” we cried as one. Roger Zelazny’s Nine Princes in Amber and thought that Mike held up the map for us to see, though Jeff and I weren’t Random was a hipper name than Corwin, even though the lat- allowed to touch it. The first room had maybe ten doors in it. ter was clearly the man. He lasted exactly one encounter. Orcs. One portal looked especially inviting, with multi-colored veils My second PC was a thief named Roulette, which I thought drawn before an archway. I pointed, and the others agreed. was a clever name. Roulette enjoyed a longer career: roughly “Are you sure you want to go there?” asked Mike. one session. Near the end, after suffering through Roulette’s “Yeah. I want a vorpal sword,” I said greedily. determined efforts to search every 10’-square of floor, wall, and “It’s the most dangerous place in the dungeon,” he warned. ceiling in the dungeon, Jeff the DM decided on a whim that the “I’ll wait and see what happens to him,” said Jeff. The coward. wall my thief had just searched was, in fact, coated with contact “C’mon, guys! If we work together, we can make it.” I really poison. I rolled a three to save. wanted a vorpal sword. One by one they demurred, until I Thus ensued my first player-DM argument. There wasn’t declared I’d go by myself and keep all the treasure I found. -

Ancient Chinese Seasons Cylinder (The Four Beasts)

A Collection of Curricula for the STARLAB Ancient Chinese Seasons Cylinder (The Four Beasts) Including: The Skies of Ancient China I: Information and Activities by Jeanne E. Bishop ©2008 by Science First/STARLAB, 95 Botsford Place, Buffalo, NY 14216. www.starlab.com. All rights reserved. Curriulum Guide Contents The Skies of Ancient China I: Information and Activities The White Tiger ..............................................14 Introduction and Background Information ..................4 The Black Tortoise ............................................15 The Four Beasts ......................................................8 Activity 2: Views of the Four Beasts from Different The Blue Dragon ...............................................8 Places in China ....................................................17 The Red Bird .....................................................8 Activity 3: What’s Rising? The Four Great Beasts as Ancient Seasonal Markers .....................................21 The White Tiger ................................................8 Activity 3: Worksheet ......................................28 The Black Tortoise ..............................................9 Star Chart for Activity 3 ...................................29 The Houses of the Moon ........................................10 Activity 4: The Northern Bushel and Beast Stars .......30 In the Blue Dragon ...........................................10 Activity 5: The Moon in Its Houses ..........................33 In the Red Bird ................................................10 -

The Demon Haunted World

THE DEMON- HAUNTED WORLD Science as a Candle in the Dark CARL SAGAN BALLANTINE BOOKS • NEW YORK Preface MY TEACHERS It was a blustery fall day in 1939. In the streets outside the apartment building, fallen leaves were swirling in little whirlwinds, each with a life of its own. It was good to be inside and warm and safe, with my mother preparing dinner in the next room. In our apartment there were no older kids who picked on you for no reason. Just the week be- fore, I had been in a fight—I can't remember, after all these years, who it was with; maybe it was Snoony Agata from the third floor— and, after a wild swing, I found I had put my fist through the plate glass window of Schechter's drug store. Mr. Schechter was solicitous: "It's all right, I'm insured," he said as he put some unbelievably painful antiseptic on my wrist. My mother took me to the doctor whose office was on the ground floor of our building. With a pair of tweezers, he pulled out a fragment of glass. Using needle and thread, he sewed two stitches. "Two stitches!" my father had repeated later that night. He knew about stitches, because he was a cutter in the garment industry; his job was to use a very scary power saw to cut out patterns—backs, say, or sleeves for ladies' coats and suits—from an enormous stack of cloth. Then the patterns were conveyed to endless rows of women sitting at sewing machines. -

Dragon Keepers Rules

By Catarina Lacerda and Vital Lacerda Introduction Dragon Keepers is a game representing a battle between two forces. The first is a group of evil hunters who want to destroy dragons for trophies and fame. The other group is the heroic dragon keepers who protect the dragons. Each player represents the chief of a specific tribe of dragon keepers who will defend the dragons from attacks by the evil hunters. In Dragon Keepers there are 2 different modes of game play. Both modes are played over several rounds until players have reached a game ending condition. The game modes are the following: Keeper Game (suitable for ages 6+) Dragon Game (suitable for ages 9+) A light competitive game using “push your luck” A cooperative game which takes 30-40 minutes and plays mechanisms, which takes 10-15 minutes and plays from 3 to from 2 to 4 players. This mode requires a bit more strategic 6 players. This mode is a lighter version of the game thinking and is more suited for adults and older children. intended for younger children. The goal for each player is to The goal for the players is to train a predetermined number heroically defend 3 different dragons from the evil hunter. of dragons and have them successfully attack the Hunter. Components 18 Magic cards 36 Keeper cards (6 Keeper decks with 6 cards each) 18 Shield tokens (Red, Yellow, Green, Blue, Purple, and White) 6 Dragon tiles 15 Arrow tokens 5 Flame tokens 36 Action tokens (12 Defense, 8 Heal, 8 Training, and 8 Attack) 1 double-sided Hunter card and 4 Hunter cards 8 D6 Black Hunter dice 12 D6 Battle dice (6 White and 6 Red) 4 Player aid cards Game Fundamentals This section is an overview of everything that is common between both game modes. -

The Story of the Dragon of Moston

The Story of the Dragon of Moston Well, if you were to go looking for Moston, you'd find it betwixt Sandbach and Middlewich. It is only a little place now with a few folk living there, and when you hear this you'll see why that may be. Now, the people of Moston were a happy and jolly lot who made most of their living from the fine apple trees in their orchard. They bore the largest and juiciest apples in all of Cheshire, and in truth the rest of the county were more than a little jealous of this. The apples of Moston were bigger than even your head. And a fine head it is you have sir. The people of the village didn't know why it was that their apples grew so large, but I do, and I'll tell you. The apples grew in an orchard which was beside a boggy marsh, full of dark, dank swamp water. The trees reached out their roots through the soil and into that marsh and drew the water up along the roots, rising through the trunk, along the branches and caused those apples to swell. The people of Moston looked forward to those days at the end of summer with autumn beginning to make itself felt in the air, the days when the apples would be ripening and ready for the harvest and they eagerly awaited the day to go picking, dreaming of the juice trickling down chins, or the warm smell of the apples baking. And now the day was here! Each of the Moston folk headed out to whichever tree in the orchard which was their own, carrying baskets and buckets ready to be filled.