Sylvia Dovlén

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

The Mid-Term Evaluation of Usaid/Pact/Teach Program Report

THE MID-TERM EVALUATION OF USAID/PACT/TEACH PROGRAM REPORT Ethio-Education Consultants (ETEC) Piluel ABE Center - Itang October 2008 Addis Ababa Ethio-Education Consultants (ETEC) P.O. Box 9184 A.A, Tel: 011-515 30 01, 011-515 58 00 Fax (251-1)553 39 29 E-mail: [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Ethio-Education Consultants (ETEC) would like to acknowledge and express its appreciation to USAID/ETHIOPIA for the financial support and guidance provided to carryout the MID-TERM EVALUATION OF USAID/PACT/TEACH PROGRAM, Cooperative Agreement No. 663-A-00-05-00401-00. ETEC would also like to express its appreciation and gratitude: To MoE Department of Educational Planning and those RSEBs that provided information despite their heavy schedule To PACT/TEACH for familiarizing their program of activities and continuous response to any questions asked any time by ETEC consultants To PACT Partners for providing relevant information and data by filling out the questionnaires and forms addressed to them. To WoE staff, facilitators/teachers and members of Center Management Committees (CMCs) for their cooperation to participate in Focus Group Discussion (FDG) ACRONYMS ABEC Alternative Basic Education Center ADA Amhara Development Association ADAA African Development Aid Association AFD Action for Development ANFEAE Adult and Non-Formal Education Association in Ethiopia BES Basic Education Service CMC Center Management Committee CTE College of Teacher Education EDA Emanueal Development Association EFA Education For All EMRDA Ethiopian Muslim's Relief -

Views of Soil Erosion Problems and Their Conservation Knowledge at Beressa Watershed, Central Highland of Ethiopia

International Journal of Agriculture and Environmental Research ISSN: 2455-6939 Volume:04, Issue:04 "July-August 2018" ASSESSMENTS OF FARMERS’ PERCEPTION ON SOIL EROSION AND SOIL AND WATER CONSERVATION MEASURES: IN CASE OF ARSI NEGELE WOREDA, CENTRAL ETHIOPIA. Dulo Husen* Adami Tulu Agricultural Research Center, Zeway, Ethiopia. ABSTRACT This study was conducted in Arsi Negelle woreda of West Arsi Zone, Oromia regional state. The main objective of the study was to assess the farmer’s perception on soil erosion and soil bunds construction and to assess the benefit obtained from soil bund construction in Arsi Negelle woreda. Three representative sites were selected purposively. The data was collected from three sites namely: lowland, midland and highland. 131-households were selected randomly from six kebeles. The analysis was carried using SPSS software. Both closed and open-ended types of questionnaires were used. The 50.4%, 44.3% and 5.3% of respondents were said that, major causes of soil erosion were absences of soil and water conservation and deforestation, absences of soil and water conservation and overgrazing and ploughing along slope respectively. The survey results showed that 63.4 % of sampled households were benefited (yield, moisture and soil fertility is increased) from practicing of soil and water conservation on their farmland, whereas 36.6 % of respondents said that they were not benefited from practicing of soil bund on their farmland. According to the survey result showed 37.4% and 26% of respondents were got technical advices concerning soil bund technologies from DAs and district Agricultural experts respectively. In conclusion, this study provided as soil bunds and soil erosion had significant effect in the study area. -

Malt Barley Value Chain in Arsi and West Arsi Highlands of Ethiopia

Academy of Social Science Journals Received 10 Dec 2020 | Accepted 15 Dec 2020 | Published Online 29 Dec 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/DOI 10.15520/assj.v5i12.2612 ASSJ 05 (12), 1779−1793 (2020) ISSN : 2456-2394 RESEARCH ARTICLE Malt Barley Value Chain in Arsi and West Arsi highlands of Ethiopia Bedada Begna1 , Mesay Yami2 1 Kulumsa Agricultural Research Abstract Center, Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR) The study was undertaken in four districts of Arsi and West Arsi zones where malt barley is highly produced. Different participatory 2Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural rural appraisal approaches were employed to conduct the study. The Research (EIAR), National findings indicated that land allotted for malt barley production has been Fishery and Aquatic Life Research increased in the study areas since 2010, scarcity was noticed due to Center (NAFALRC) constraints related to quality and existence of malt barley competing outlets. Malt barley marketing is complex and dynamic where various actors are involved in its marketing. The marketing route changes over time depending on the demands at the terminal markets. Assela Malt Factory (AMF) plays a great role in determining malt barley price while producers are price takers. Among five major malt barley marketing channels only three of them are supplying to the factory. AMF accessed to 90% of malt barley from the channel via traders and the direct supply by farmers via cooperatives was not more than 10%. The channel via cooperatives which is strategic for both producers and the factory was serving below anticipated due to the financial constraints and management skill gaps of the cooperatives. -

Time to First-Line Antiretroviral Treatment Failure and Its Predictors Among HIV-Positive Children in Shashemene Town Health Facilities, Oromia Region, Ethiopia, 2019

Hindawi e Scientific World Journal Volume 2021, Article ID 8868479, 9 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8868479 Research Article Time to First-Line Antiretroviral Treatment Failure and Its Predictors among HIV-Positive Children in Shashemene Town Health Facilities, Oromia Region, Ethiopia, 2019 Endale Zenebe,1 Assefa Washo ,2 and Abreham Addis Gesese 1 1Jimma University, College of Public Health and Medical Science, Department of Epidemiology, Jimma, Ethiopia 2Hawassa College of Health Science, Department of Public Health, Hawassa, Ethiopia Correspondence should be addressed to Assefa Washo; [email protected] Received 8 September 2020; Revised 30 June 2021; Accepted 9 July 2021; Published 18 August 2021 Academic Editor: Jacek Karwowski Copyright © 2021 Endale Zenebe et al. +is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. With expanding pediatric antiretroviral therapy access, children will begin to experience treatment failure and require second-line therapy. In resource-limited settings, treatment failure is often diagnosed based on the clinical or immunological criteria which occur way after the occurrence of virological failure. Previous limited studies have evaluated immunological and clinical failure without considering virological failure in Ethiopia. +e aim of this study was to investigate time to first-line antiretroviral treatment failure and its predictors in Shashamene town health facilities with a focus on virological criteria. Methods. A ret- rospective cohort study was conducted in three health facilities of Shashamene town, Oromia Regional State, from March 1 to 26, 2019. Children aged less than 15 years living with HIV/AIDS that were enrolled on ART between January 1, 2011, and December 30, 2015, in Shashamene town health facilities were the study population. -

On-Farm Phenotypic Characterization And

ON-FARM PHENOTYPIC CHARACTERIZATION AND CONSUMER PREFERENCE TRAITS OF INDIGENOUS SHEEP TYPE AS AN INPUT FOR DESIGNING COMMUNITY BASED BREEDING PROGRAM IN BENSA DISTRICT, SOUTHERN ETHIOPIA MSc THESIS HIZKEL KENFO DANDO FEBRUARY 2017 HARAMAYA UNIVERSITY, HARAMAYA On-Farm Phenotypic Characterization and Consumer Preference Traits of Indigenous Sheep Type as an Input for Designing Community Based Breeding Program in Bensa District, Southern Ethiopia A Thesis Submitted to the School of Animal and Range Sciences, Directorate for Post Graduate Program HARAMAYA UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ANIMAL GENETICS AND BREEDING Hizkel Kenfo Dando February 2017 Haramaya University, Haramaya HARAMAYA UNIVERSITY DIRECTORATE FOR POST GRADUATE PROGRAM We hereby certify that we have read and evaluated this Thesis entitled “On-Farm Phenotypic Characterization and Consumer Preference Traits of Indigenous Sheep Type as an Input for Designing Community Based Breeding Program in Bensa District, Southern Ethiopia” prepared under our guidance by Hizkel Kenfo Dando. We recommend that it be submitted as fulfilling the Thesis requirement. Yoseph Mekasha (PhD) __________________ ________________ Major Advisor Signature Date Yosef Tadesse (PhD) __________________ ________________ Co-Advisor Signature Date As a member of the Board of Examiners of the MSc Thesis Open Defense Examination, we certify that we have read and evaluated the Thesis prepared by Hizkel Kenfo Dando and examined the candidate. We recommend -

WCBS III Supply Side Report 1

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Capacity Building in Collaboration with PSCAP Donors "Woreda and City Administrations Benchmarking Survey III” Supply Side Report Survey of Service Delivery Satisfaction Status Final Addis Ababa July, 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The survey work was lead and coordinated by Berhanu Legesse (AFTPR, World Bank) and Ato Tesfaye Atire from Ministry of Capacity Building. The Supply side has been designed and analysis was produced by Dr. Alexander Wagner while the data was collected by Selam Development Consultants firm with quality control from Mr. Sebastian Jilke. The survey was sponsored through PSCAP’s multi‐donor trust fund facility financed by DFID and CIDA and managed by the World Bank. All stages of the survey work was evaluated and guided by a steering committee comprises of representatives from Ministry of Capacity Building, Central Statistical Agency, the World Bank, DFID, and CIDA. Large thanks are due to the Regional Bureaus of Capacity Building and all PSCAP executing agencies as well as PSCAP Support Project team in the World Bank and in the participating donors for their inputs in the Production of this analysis. Without them, it would have been impossible to produce. Table of Content 1 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Key results by thematic areas............................................................................................................ 1 1.1.1 Local government finance ................................................................................................... -

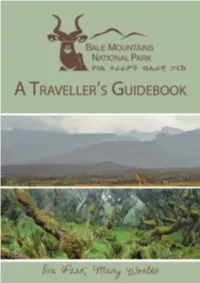

Bale-Travel-Guidebook-Web.Pdf

Published in 2013 by the Frankfurt Zoological Society and the Bale Mountains National Park with financial assistance from the European Union. Copyright © 2013 the Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority (EWCA). Reproduction of this booklet and/or any part thereof, by any means, is not allowed without prior permission from the copyright holders. Written and edited by: Eliza Richman and Biniyam Admassu Reader and contributor: Thadaigh Baggallay Photograph Credits: We would like to thank the following photographers for the generous donation of their photographs: • Brian Barbre (juniper woodlands, p. 13; giant lobelia, p. 14; olive baboon, p. 75) • Delphin Ruche (photos credited on photo) • John Mason (lion, p. 75) • Ludwig Siege (Prince Ruspoli’s turaco, p. 36; giant forest hog, p. 75) • Martin Harvey (photos credited on photo) • Hakan Pohlstrand (Abyssinian ground hornbill, p. 12; yellow-fronted parrot, Abyssinian longclaw, Abyssinian catbird and black-headed siskin, p. 25; Menelik’s bushbuck, p. 42; grey duiker, common jackal and spotted hyena, p. 74) • Rebecca Jackrel (photos credited on photo) • Thierry Grobet (Ethiopian wolf on sanetti road, p. 5; serval, p. 74) • Vincent Munier (photos credited on photo) • Will Burrard-Lucas (photos credited on photo) • Thadaigh Baggallay (Baskets, p. 4; hydrology photos, p. 19; chameleon, frog, p. 27; frog, p. 27; Sof-Omar, p. 34; honey collector, p. 43; trout fisherman, p. 49; Finch Habera waterfall, p. 50) • Eliza Richman (ambesha and gomen, buna bowetet, p. 5; Bale monkey, p. 17; Spot-breasted plover, p. 25; coffee collector, p. 44; Barre woman, p. 48; waterfall, p. 49; Gushuralle trail, p. 51; Dire Sheik Hussein shrine, Sof-Omar cave, p. -

Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics

OPEN ACCESS Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics June 2018 ISSN 2006-9774 DOI: 10.5897/JDAE www.academicjournals.org ABOUT JDAE The Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics (JDAE) is published monthly (one volume per year) by Academic Journals. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics (JDAE) (ISSN:2006-9774) is an open access journal that provides rapid publication (monthly) of articles in all areas of the subject such as The determinants of cassava productivity and price under the farmers’ collaboration with the emerging cassava processors, Economics of wetland rice production technology in the savannah region, Programming, efficiency and management of tobacco farms, review of the declining role of agriculture for economic diversity etc. The Journal welcomes the submission of manuscripts that meet the general criteria of significance and scientific excellence. Papers will be published shortly after acceptance. All articles published in JDAE are peer- reviewed. Contact Us Editorial Office: [email protected] Help Desk: [email protected] Website: http://www.academicjournals.org/journal/JDAE Submit manuscript online http://ms.academicjournals.me/ Editors Editorial Board Members Dr. Austin O. Oparanma Prof. S. Mohan Rivers State University of Science and Dept. of Civil Engineering Technology Indian Institute of Technology Port Harcourt, Madras Nigeria. Chennai, India. Silali Cyrus Wanyonyi Yatta School of Agriculture Nairobi, Dr. Siddhartha Sarkar Kenya. A.C. College of Commerce Jalpaiguri Dr. Henry de-Graft Acquah India Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension School of Agriculture University of Cape Coast Cape Coast, Ghana. Dr. Edson Talamini Federal University of Grande Dourados - UFGD Cidade Universitária Dourados, Brazil. Dr. Benjamin Chukwuemeka Okoye National Root Crops Research Institute Umudike, Nigeria. -

Overview of the Industry +251- 944 252 715 +251-913 254 073 Fax: +251-115 505 127 E-Mail: [email protected]

Ethiopian Horticulture & Agriculture Investment Authority (EHAIA): New horticulture development cluster in Ethiopia --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Overview of the industry Ethiopia is one of the countries in Africa which has huge potential for the production of different varieties of horticultural crops. The country is endowed with extensive natural resources in different agro-ecological zones suitable for production of a number of flowers, vegetables, fruits and herbs. Export horticulture is booming and the country is now the second largest supplier and exporter of highest quality flowers from Africa. Currently, close to 130 companies are engaged in horticultural crop production of which the largest percentage is owned by foreign investors. The country initiated cluster based investment in horticulture export ventures and identified suitable corridors to offer attractive business and investment environments. This cluster based investment provides good infrastructure connectivity stimulating strategic investment opportunities across the sector and among domestic and international development partners. It further harmonizes regulatory and policy frameworks to maximize the socio- economic advantage of the sector. Based on this new initiation, EHAIA conducted land suitability analysis, developed master plan for two corridors: Alage and Shallo and confirmed that two clusters are found to be Tel: + 251 -115 502 483 suitable for the production of flowers, -

ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL of GRADUATE STUDIES Environmental Science Program

ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES Environmental Science Program Impact of ‘Katikala’ Production on the Degradation of Woodland Vegetation and Emission of CO and PM during Distillation in Arsi-Negele Woreda, Central Rift Valley of Ethiopia By Nejibe Mohammed A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of Addis Ababa University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Environmental science February, 2008 Environmental Impact of ‘Katikala’ Production in Arsi-Negele Woreda, Central Rift Valley of Ethiopia A Thesis Submitted to the School Of Graduate Studies of Addis Ababa University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Environmental Science By Nejibe Mohammed Addis Ababa University Faculty of Science, Environmental Science Program February 2008 ACKNOWLEDGMENT First of all I am deeply indebted to my advisors: Dr Mekuria Argaw and Dr. Seyoum Leta for their diligent and Constructive comments, guidance and flexible supervision and continuous follow up. I wish to thank Addis Ababa University for giving me the chance to join the graduate studies of environmental science program. I need to also express my genuine thanks to horn of Africa regional environment program for providing me with financial support special thanks goes to Ato Negussu Aklilu, Forum for Environment (FfE) for his cooperation. I would also like to thank Ato Dekebo Dale, Arsi Negele Concern for Environment and Development Association (ANCEDA) for his continuous cooperation in providing me with valuable information during the field work. I am particularly indebted to GTZ – SUN Energy project who gave me logistic support for accomplishing this thesis. -

Ethiopia Budget Birding 25Th November to 6Th December 2019 (12 Days)

Ethiopia Budget Birding th th 25 November to 6 December 2019 (12 days) Trip Report Stresemann’s Bush Crow by Gareth Robbins Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Gareth Robbins Trip Report – RBL Ethiopia – Budget Birding 2019 2 Tour in Detail Today was the first full day of the tour and after an early breakfast, we left Addis Ababa just in time to miss the traffic and made our way to the town of Debre Birhan. We saw a good number of birds along the way such as Red-breasted Wheatear, the huge Thick-billed Raven, Wattle Ibis, Ortolan Buntings, a large flock of Ethiopian Siskins, Thekla’s Larks, Lanner Falcons, Common Kestrel and an Augur Buzzard. We stopped at a small village just outside the town of Debre Birhan and got fantastic looks at Bearded Vultures as they flew overhead. We also got a long distant view of two Blue-winged Geese. We visited the Debre Birhan Rubbish Dump and got to see some Hooded Vultures, Black Kites and a Tawny Eagle. On the other side of the town, we managed to see Three-banded Plover, Wood Sandpiper, two Abyssinian Longclaws and a female Northern Fiscal impaling an unlucky grasshopper onto the Bearded Vulture by Gareth Robbins barbs of a barbed-wire fence. We then checked into our hotel and had an entertaining lunch before we took the long drive up to three thousand metres above sea level to a place called Gemasa Gedel which was covered by some dark thick cloud. Visibility was terrible here and it was freezing.