PDF of All the Resources and Materials in This Unit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'I Want to Go to Jail': the Woman's Party

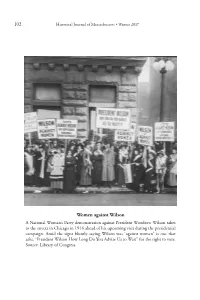

102 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2017 Women against Wilson A National Woman’s Party demonstration against President Woodrow Wilson takes to the streets in Chicago in 1916 ahead of his upcoming visit during the presidential campaign. Amid the signs bluntly saying Wilson was “against women” is one that asks, “President Wilson How Long Do You Advise Us to Wait” for the right to vote. Source: Library of Congress. 103 “I Want to Go to Jail”: The Woman’s Party Reception for President Wilson in Boston, 1919 JAMES J. KENNEALLY Abstract: Agitation by the National Woman’s Party (NWP) was but one of several factors leading to the successful passage of the Nineteenth Amendment and woman suffrage. By turning to direct action, concentrating on a federal amendment, and courting jail sentences (unlike the more restrained National American Woman Suffrage Association), they obtained maximum publicity for their cause even when, as in Boston, their demonstration had little direct bearing on enfranchisement. Although historians have amply documented the NWP’s vigils and arrests before the White House, the history of the Massachusetts chapter of the NWP and the story of their demonstrations in Boston in 1919 has been mostly overlooked. This article gives these pioneering suffragists their recognition. Nationally, the only women to serve jail sentences on behalf of suffrage were the 168 activists arrested in the District of Columbia and the sixteen women arrested in Boston. Dr. James J. Kenneally, a Professor Emeritus and former Director of Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 45 (1), Winter 2017 © Institute for Massachusetts Studies, Westfield State University 104 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2017 the Martin Institute at Stonehill College, has written extensively on women’s history.1 * * * * * * * Alice Paul (1885–1977) and Lucy Burns (1879–1966) met in jail in 1909 in England. -

The Fifteenth Star: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party in Minnesota

The Fifteenth Star Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party in Minnesota J. D. Zahniser n June 3, 1915, Alice Paul hur- Oriedly wrote her Washington headquarters from the home of Jane Bliss Potter, 2849 Irving Avenue South, Minneapolis: “Have had con- ferences with nearly every Suffragist who has ever been heard of . in Minnesota. Have conferences tomor- row with two Presidents of Suffrage clubs. I do not know how it will come out.”1 Alice Paul came to Minnesota in 1915 after Potter sought her help in organizing a Minnesota chapter of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CU). The CU was a new- comer on the national suffrage scene, founded by Paul in 1913. She focused on winning a woman suffrage amend- ment to the US Constitution. Paul, a compelling— even messianic— personality, riveted attention on a constitutional amendment long Alice Paul, 1915. before most observers considered it viable; she also practiced more frage Association (MWSA), had ear- she would not do. I have spent some assertive tactics than most American lier declined to approve a Minnesota hours with her.”3 suffragists thought wise.2 CU chapter; MWSA president Clara After Paul’s visit, Ueland and the Indeed, the notion of Paul coming Ueland had personally written Paul to MWSA decided to work cooperatively to town apparently raised suffrage discourage a visit. Nonetheless, once with the Minnesota CU; their collabo- hackles in the Twin Cities. Paul wrote Paul arrived in town, she reported ration would prove a marked contrast from Minneapolis that the executive that Ueland “has been very kind and to the national scene. -

Nurses Fight for the Right to Vote: Spotlighting Four Nurses Who Supported the Women’S Suffrage Movement

Archived version from NCDOCKS Institutional Repository http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/asu/ Nurses Fight For The Right To Vote: Spotlighting Four Nurses Who Supported The Women’s Suffrage Movement By: Phoebe Pollitt, PhD, RN Abstract The Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees women the right to vote. Its ratification in 1920 represented the culmination of a decades-long fight in which thousands of women and men marched, picketed, lobbied, and gave speeches in support of women’s suffrage. This article provides a closer look at the lives of four nurse suffragists—Lavinia Lloyd Dock, Mary Bartlett Dixon, Sarah Tarleton Colvin, and Hattie Frances Kruger—who were arrested for their involvement in the women’s suffrage movement. Pollitt, Phoebe. (2018). "Nurses Fight for the Right to Vote." AJN The American Journal of Nursing: November 2018 - Volume 118 - Issue 11 - p 46–54. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000547639.70037.cd. Publisher version of record available at: https://journals.lww.com/ajnonline/Fulltext/2018/11000/ Nurses_Fight_for_the_Right_to_Vote.27.aspx. NC Docks re-print is not the final published version. Nurses Fight for the Right to Vote Spotlighting four nurses who supported the women’s suffrage movement. By Phoebe Pollitt, PhD, RN ABSTRACT: The Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees women the right to vote. Its rat- ification in 1920 represented the culmination of a decades-long fight in which thousands of women and men marched, picketed, lobbied, and gave speeches in support of women’s suffrage. This article provides a closer look at the lives of four nurse suffragists—Lavinia Lloyd Dock, Mary Bartlett Dixon, Sarah Tarleton Colvin, and Hattie Frances Kruger—who were arrested for their involvement in the women’s suffrage movement. -

In This Issue

The Ol’ Pioneer The Magazine of the Grand Canyon Historical Society Volume 31 : Number 4 www.GrandCanyonHistory.org Fall 2020 In This Issue Suff’s Campaign Gains Steam at El Tovar ....... 3 The Saga of Louis D. Boucher ............................ 6 Helen Ranney ...................................................... 14 The Bulletin ......................................................... 15 President’s Letter The Ol’ Pioneer The Magazine of the Grand Canyon Historical Society This will be my final letter to our members, as my term as President ceases at the end of 2020. Since this is my second three-year term on the Board of Volume 31 : Number 4 Directors, I will be terming off the Board. Our by-laws ensure there is an Fall 2020 orderly transition within the Board of Directors. By January 2021, you our u members will have selected five new or reelected people, and they will begin The Historical Society was established to serve their first or second three-year terms. Keep watch for an election in July 1984 as a non-profit corporation email in November; we do not plan to mail paper ballots. to develop and promote appreciation, Six years ago when I attended my first Board meeting, as I learned about all understanding and education of the the great GCHS programs and projects, I quickly realized the importance of my earlier history of the inhabitants and new role. At that meeting, the call went out for volunteers to co-chair the 2016 important events of the Grand Canyon. Grand Canyon History Symposium. Helen Ranney had already volunteered The Ol’ Pioneer is published by the GRAND and I was aware of Helen’s great management and organizational talents from CANYON HISTORICAL SOCIETY. -

A History of Woman Suffrage in Nebraska, 1856-1320

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received g g.gg^g COULTER, Thomas Chalmer, 1926- A HISTORY OF WOMAN SUFFRAGE IN NEBRASKA, 1856-1320. The Ohio State University, 1PI.B ., 1967 History, modem University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan A HISTORY OF WOMAN SUFFRAGE IN NEBRASKA, 1856-1920 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Thomas Chalmer Coulter, B.S. in Ed., B.S., M.A. The Ohio State University 1967 Approved by Adviser Department of History VITA December 27, 1926 Born - Newark, Ohio 1951............. B.S. in Ed., B.S., Kent State University, Kent, Ohio 1951-1957 .... Teacher, Berlin High School, Berlin, Ohio 1954-1956 .... Graduate Study, Kent State University Summer School 1956 ......... M. A., Kent State University, Kent, Ohio 1957-1960 . Graduate Study, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1960-1961 . Instructor, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio 1961-1967 . Assistant Professor of History, Doane College, Crete, Nebraska FIELDS OF STUDY Major Field: The Social History of Nineteenth Century America 11 TABLE OF COwTEOTS VITA ................................... ii INTRODUCTION Chapter I. THE GENESIS OF THE WOMAN SUFFRAGE MOVEMENT IN NEBRASKA . 4 The Western Milieu The First Shot, 1856 II. THE POSTWAR DECADES, 1865-1882 ............. ............. 15 Continued Interest E. M. Correll Organization Progresses The First State Convention III, HOUSE ROLL NO. 162 AND ITS CONSEQUENCES, 1881-1882 .... 33 Passage of the Joint Resolution The Campaign for the Amendment Clara Bewick Colby Opposition to the Measure Mrs. Sewall’s Reply The Suffrage Associations Conventions of 1882 The Anthony-Rosewater Debate The Election of 1882 Aftermath IV. -

Delaware Women's Suffrage Timeline Compiled by the Delaware Historical Society Edited and Updated for Delaware Humanities

Delaware Women’s Suffrage Timeline Compiled by the Delaware Historical Society Edited and updated for Delaware Humanities, Summer 2019, by Anne M. Boylan 1868 Mary Ann Sorden Stuart of Greenwood begins to fight for women’s rights. Nov. 12, 1869 Wilmington’s first women’s rights convention. Abolitionist Thomas Garrett presides, Lucy Stone speaks. Delaware Suffrage Association, with Emma Worrell as Corresponding Secretary and Dr. John Cameron as Recording Secretary, founded. It affiliates with Lucy Stone’s American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). 1870’s Married women in Delaware receive the right to make wills, own property, and control their earnings. 1870s Delawareans Dr. John Cameron, Isabella Hendry Cameron, Dr. Mary Homer York Heald, Samuel D. Forbes and Mrs. Elizabeth Forbes regularly attend AWSA conventions as delegates. 1878 Mary Ann Sorden Stuart testifies before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee in favor of women’s suffrage. Stuart is the Delaware representative for the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. 1881 Mary Ann Sorden Stuart, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony address Delaware general assembly in an attempt to amend the state constitution to allow women’s suffrage. 1884 Belva Lockwood, the “woman’s rights candidate for president,” speaks at Delaware College in Newark at the invitation of the college’s women students. In 1885, the college’s trustees end co-education, an “experiment” begun in 1872. 1888 Delaware Woman’s Christian Temperance Union endorses women’s suffrage. 1890 The AWSA and NWSA unite to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). -

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Alice Paul: Woman Suffrage and Gender Bias in the American Ideal

ELIZABETH CADY STANTON, SUSAN B. ANTHONY, AND ALICE PAUL: WOMAN SUFFRAGE AND GENDER BIAS IN THE AMERICAN IDEAL A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate school of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By Joan Harkin LaCoss, Au.D. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. November 12, 2010 ELIZABETH CADY STANTON, SUSAN B. ANTHONY, AND ALICE PAUL: WOMAN SUFFRAGE AND GENDER BIAS IN THE AMERICAN IDEAL Joan Harkin LaCoss, Au.D. MALS Mentor: Kazuko Uchimura, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The woman suffrage movement in the United States was a reaction to gender bias in the American ideal. This protracted struggle started in Seneca Falls, New York, with the Women’s Rights Convention of 1848 and ended with the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1920. The suffragists encountered many obstacles both outside and inside the movement. Outside tensions grew out of the inherent masculinity of a society that subscribed to the sentiment that women should be excluded from the principles of the Declaration of Independence and the equal rights of American democracy and citizenship. Inside tensions reflected differences in ideology, philosophy, and methodology among various suffrage factions. The years of the woman suffrage movement saw many social and political events and technological advancements. However, the development that led to perhaps the greatest challenge to the cultural tradition of female inferiority was the rise of radical feminist suffragists, particularly Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Alice Paul. -

View the Delaware Women's History Timeline

Delaware Women’s Suffrage Timeline Compiled by the Delaware Historical Society. Edited and updated for Delaware Humanities, Summer 2019, by Anne M. Boylan. 1868 – Mary Ann Sorden Stuart of Greenwood begins to fight for women’s rights 1869 – Nov. 12, Wilmington’s first women’s rights convention. Abolitionist Thomas Garrett presides,Lucy Stone speaks. Delaware Suffrage 1870s Association, with Emma Worrell as Corresponding Secretaryand Dr. John Cameron as Recording – Married women in Delaware receive the right to Secretary, founded. It affiliates with Lucy Stone’s make wills, own property, and control their earnings. AmericanWoman Suffrage Association (AWSA). – Delawareans Dr. John Cameron, Isabella Hendry Cameron, Dr. Mary Homer York Heald, Samuel D. Forbes and Mrs. Elizabeth Forbes regularly attend AWSA conventions as delegates. 1878 – Mary Ann Sorden Stuart testifies before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee in favor of women’s suffrage. Stuart is the Delaware 1881 representative for the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), led by Elizabeth Cady – Mary Ann Sorden Stuart, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony address Delaware general assembly in an attempt to amend the state constitution to allow women’s suffrage. 1884 – Belva Lockwood, the “woman’s rights candi- date for president,” speaks at Delaware College in Newark at the invitation of the college’s 1888 women students. In 1885, the college’s trustees end coeducation, an “experiment” begun in 1872. – Delaware Woman’s Christian Temperance Union endorses women’s suffrage. 1890 – The AWSA and NWSA unite to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). 1895 – Commencement exercises at Howard High School feature a debate on woman suffrage and an address by Mary Church Terrell, first president of the National Association of 1896 Colored Women (NACW). -

2020 Gazette 2020 a Gazette from the National Women’S History Alliance Volume 12

Women’s History 2020 Gazette 2020 A Gazette From the National Women’s History Alliance Volume 12 My Dear Friends, 2020 is such a special year. It is not only the 100th Anniversary of women in the United States winning the right to vote, but it is also the 40th Anniversary of the National Women's History Alliance. At the end of 2020, with great joy and confidence, I will be passing the torch of leadership to a new generation. Leasa Graves, our Assistant Director, will become the new Executive Director of the National Women's History Alliance. I plan to stay on to help in whatever ways I'm needed, but the leadership, vision, and forward movement will pass to a new generation. This generation not only grew up with women making history as never before, it also witnessed an unprecedented shift in recognizing and celebrating women’s achievements. To help the Alliance continue, the Board has decided to establish an endowment in my name. Income from this endowment will be used to help the NWHA continue and expand our work of "writing women back into history." If you would like more information about the Molly Murphy MacGregor Endowment, please email me at [email protected]. I would love to talk with you about it and I would love to encourage your support. The last 40 years have been a journey that I can't describe in terms of how it has inspired, expanded and rewarded me as a person. Thank you all for your help in making it possible. -

Boosting the Mythic American West and Us Woman Suffrage

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: BOOSTING THE MYTHIC AMERICAN WEST AND U.S. WOMAN SUFFRAGE: PACIFIC NORTHWEST AND ROCKY MOUNTAIN WOMEN’S PUBLIC DISCOURSE AT THE TURN OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY Tiffany Lewis, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Kristy L. Maddux Department of Communication This project examines how white women negotiated the mythic and gendered meanings of the American West between 1885 and 1935. Focusing on arguments made by women who were active in the public life of the Pacific Northwest and Rocky Mountain States, these analyses illustrate the ways the mythic West shaped the U.S. woman suffrage movement and how Western women simultaneously contributed to the meaning of the American West. Through four case studies, I examine the ways women drew on Western myths as they advocated for woman suffrage, participated in place- making the West, and navigated the gender ideals of their time. The first two case studies attend to the advocacy discourse of woman suffragists in the Pacific Northwest. Suffragist Abigail Scott Duniway of Oregon championed woman suffrage by appropriating the frontier myth to show that by surviving the mythic trek West, Western women had proven their status as frontier heroines and earned their right to vote. Mountaineer suffragists in Washington climbed Mount Rainier for woman suffrage in 1909. By taking a “Votes for Women” pennant to the mountain summit, they made a political pilgrimage that appropriated the frontier myth and the turn-of-the- century meanings of mountain climbing and the wilderness for woman suffrage. The last two case studies examine the place-making discourse of women who lived in Rocky Mountain states that had already adopted woman suffrage. -

Finding Their Voices

FINDING THEIR VOICES The United States Constitution did not originally specify voting qualifications, allowing each state to determine who was eligible. Generally, men without property were prohibited from voting, as were women. During the 19th century, the standards changed until by mid-century all states had granted white men the right to vote regardless of property ownership. Women would wait much longer for this basic right. During the 1820s and 30s, as more men gained the vote, women started seeking equal treatment and the campaign for women’s suffrage accelerated. In July 1848, the Women’s Rights Convention (also known as the Seneca Falls Convention) was held in Seneca Falls, New York, the home of Elizabeth Cady Stanton who was one of the event’s organizers. Promoted as a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of women, the convention focused on a number of topics, including suffrage. The convention issued the “Declaration of Sentiments,” a statement of grievances and demands patterned closely after the Declaration of Independence. It called upon women to organize and petition for their rights. The convention passed 12 resolutions designed to gain certain rights and privileges that women of the era were denied. Among these was a resolution demanding the right to vote. While ridiculed by many at the time, this resolution became the foundation of the women’s suffrage movement. Illustration from Harper’s Weekly depicting the May 1859 session of the Woman’s Rights Convention. The image is captioned “The Orator of the Day Denouncing the Lords of Creation.” DIVISION IN THE RANKS During the 1850s, the women’s rights movement gathered steam, but it lost momentum during the Civil War. -

Alice Paul and the Virtues of Unruly Constitutional Citizenship Lynda G

Parades, Pickets, and Prison: Alice Paul and the Virtues of Unruly Constitutional Citizenship Lynda G. Dodd♦ INTRODUCTION 340 I. THE NINETEENTH AMENDMENT & UNRULY CONSTITUTIONALISM 344 A. From Partial Histories to Analytical Narratives 346 B. A Case Study of Popular Constitutionalism: The Role of Contentious Politics 353 II. ALICE PAUL’S CIVIC EDUCATION 354 A. A Quaker Education for Social Justice 355 B. A Militant in Training: The Pankhurst Years 356 C. Ending the “Doldrums”: A New Campaign for a Federal Suffrage Amendment 359 III. “A GENIUS FOR ORGANIZATION” 364 A. “The Great Demand”: The 1913 Suffrage Parade 364 B. Targeting the President 372 C. The Rise of the Congressional Union 374 D. The Break with NAWSA 377 E. Paul’s Leadership Style & the Role of “Strategic Capacity” 379 F. Campaigning Against the Democratic Party in 1914 382 G. Stalemate in Congress 387 H. The National Woman’s Party & the Election of 1916 391 ♦ J.D. Yale Law School, 2000, Ph.D Politics, Princeton University, 2004. Assistant Professor of Law, Washington College of Law, American University. Many thanks to the participants who gathered to share their work on “Citizenship and the Constitution” at the Maryland/Georgetown Discussion Group on Constitutionalism and to the faculty attending the D.C.-Area Legal History Workshop. I would like to thank Mary Clark, Ross Davies, Mark Graber, Dan Ernst, Jill Hasday, Paula Monopoli, Carol Nackenoff, David Paull Nickles, Julie Novkov, Alice Ristroph, Howard Schweber, Reva Siegel, Jana Singer, Rogers Smith, Kathleen Sullivan, Robert Tsai, Mariah Zeisberg, Rebecca Zeitlow, and especially Robyn Muncy for their helpful questions and comments.