Geesey MA Thesis Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hunting High and Low: 30Th Anniversary Super Deluxe

A-ha – Hunting High And Low: 30th Anniversary Super Deluxe (37:11, k.A., k.A., k.A., k.A.; 4 CDs, 1 DVD; Warner Music Germany, 1985/2015) A-ha veröffentlichen zum 30- jährigen Jubiläum ihres internationalen Durchbruchs das remasterte Debütalbum „Hunting High And Low“ in einer „Super Deluxe“-Ausgabe. Der neue Sound ist luftig leicht, klar und detailreich. Neben den vier CDs mit dem remasterten Material, diversen B-Sides und bisher unveröffentlichten Demos, enthält das Re-Issue auch eine DVD und ein 60-seitiges Booklet mit selten gezeigten Fotos und Geschichten zur Entstehung des Albums. Für echte Fans hört sich die Zusammenstellung des Paketes sehr verheißungsvoll an. Darf man jetzt schon über den Kauf von Weihnachtsgeschenken nachdenken? Disc 1 – The Album 01. Take On Me 02. Train Of Thought 03. Hunting High And Low 04. The Blue Sky 05. Living A Boy’s Adventure Tale 06. The Sun Always Shines On T.V. 07. And You Tell Me 08. Love Is Reason 09. I Dream Myself Alive 10. Here I Stand And Face The Rain Disc 2 – The Demos 1982-1984 01. Lesson One (Autumn 1982 “Take On Me” Demo) 02. Presenting Lily Mars (Naersnes Demo) 03. Nå Blåser Det På Jorden (Naersnes Demo) 04. The Sphinx (Naersnes Demo) 05. Living A Boy’s Adventure Tale (Naersnes Demo) 06. Dot The I 07. The Love Goodbye 08. Nothing To It 09. Go To Sleep 10. Train Of Thought (Demo) 11. Monday Mourning 12. All The Planes That Come In On The Quiet 13. The Blue Sky (Demo) 14. -

Den Ferdige Katalogen.Pdf

DET JØDISKE ÅRET — AlT TIL SIN TID 2011 © jødisk museum i oslo INNHOLDSLISTE CONTENTS 5 Å bevare fortiden for fremtiden 89 Chanuka Preserving the Past for the Future 93 Trærnes nyttår 7 Fra idé til levende museum New Year for Trees UTSTILLINGEN From Idea to a Living Museum 95 Purim 10 DET JØDISKE ÅRET – ALT TIL SIN TID Utstillingen «Friheten vinnes ikke bare én gang» 96 Ester redder sitt folk THE JEWISH YEAR – TO EVERYTHING The exhibit “Freedom is Never Won Once and for All” Esther Saves Her People THERE IS A SEASON 13 Den jødiske kalenderen 100 Kosherkjøkken The Jewish Calendar The Kosher Kitchen 16 Litterært blikk på Den jødiske kalenderen 105 Om å være jøde i Norge i dag Faglig utstillingsgruppe Bjarte Bruland A Literary View: The Jewish Calendar On Being Jewish in Norway Lynn Feinberg 20 Torill Torp-Holte Nøkkelfortellingene 107 Toraruller Sidsel Levin 13 Key Narratives The Torah Scrolls Kari Margrethe Hamkoll 29 Det jødiske året 110 Torarullen i museet Mats Tangestuen The Jewish Year The Torah in the Museum Carol Eckmann 31 Shabbat 113 Toraskapet Tekst og litteraturkommentarer Torill Torp-Holte 36 Litterært blikk på Shabbat The Torah Ark A Literary View: Shabbat 114 Toraskapets stil og ornamentering Grafisk design og koordinering Bison Design/Anita Myhrvold 39 Pesach The Style and Ornamentation of the Torah Ark Grafisk assistent Tina Blomqvist Interiørdesign Frøystad + Klock 47 Omertellingen 119 Synagogen som levde i 21 år Produksjon og oppsetting av utstillingsmoduler Per Bjerke AS Counting of the Omer A Hub of Jewish Life for 21 -

A Phonological Analysis of Songs by Norwegian Singers Sung in English

American, British or Norwegian English?: A Phonological Analysis of Songs by Norwegian Singers Sung in English René Asgautsen Master’s Thesis in English Phonetics Department of Foreign Languages University of Bergen May 2017 Acknowledgements First I would like to thank my supervisor, Kevin McCafferty for his guidance, motivation and constructive criticism. Sorry for always getting the stylesheet wrong! And thanks to Christian Utigard for feedback. I would also like to thank all the other English Master students, friends and family and my neighbors who had to endure me listening to all the songs I used in the thesis. And thanks to Morten Harket, Hans-Erik Dyvik Husby, Sverre Kjelsberg (Rest in peace), Marit Larsen, Alex Rinde, Ida Maria Sivertsen and Jahn Teigen for recording the songs. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ii TABLE OF CONTENTS iii List of Tables vii List of Figures viii 1.0 Introduction……………………………………………..……………………………… 1 1.1 Aim and Scope…………………………………………..………………………………. 1 1.2 About the Singers……………………………………….………………………………. 2 1.3 Sverre Kjelsberg………………………………………....……………………………….3 1.4 Jahn Teigen ………………………………………………………………………………3 1.5 Morten Harket …………………………………………..……………………………….4 1.6 Hans-Erik Dyvik Husby …………………………………………………………………4 1.7 Alex Rinde ……………………………………………….……………………………….6 1.8 Marit Larsen …………………………………………….……………………………….7 1.9 Ida Maria Sivertsen ……………………………………...………………………………7 1.10 Data and Methods ……………………………………..……………………………….8 1.11 The Subject of English in Norwegian Schools ……………………………………….10 2.0 Background ……………………………………………..………………………………12 -

The Cave Chronicle 5

Thomaston High School’s The Cave Chronicle 5 1 Table of Contents Blood Drive - Page 3 Kindness Committee- Page 4 Mr. McMullen Interview - Page 6 Geometry Bubble - Page 9 Thomaston History - Page 10 This Month in Music History - Page 11 Weezer’s Teal Album - Page 13 Film Reviews - Page 14 PSA to People Getting Dropped Off - Page 15 Shower Thoughts - Page 16 Word Search - Page 17 2 Red Cross Blood Drive By Jackie Swanson On Tuesday, January 8th, Interact, National Honor Society and Student Council joined together to host a Red Cross blood drive. Donators flowed in and out to give around one pint of blood to help people in need. Even with the 2 hour delay, the drive went by smoothly and there were many students, staff members, and others who were able to participate. There is always a need for blood donations, but with the recent forest fires in California along with other situations, the Red Cross is looking for as many donations as they can get. The National Honor Society will be holding another blood drive in March, so if you are eligible to donate, please consider participating! For more information on your eligibility or other ways to help, visit: https://www.redcrossblood.org/ 3 Kindness Committee By Mel Shkrepi THS students are buzzing all around with talk of THS’ new club, the Kindness Committee! The Kindness Committee is a club formed by students who attended the Berkshire League School Climate Summit at Northwestern High School last month. The summit was a day of learning all about ways to implement a kinder climate into your school and community, and various activities such as “Kindness in Motion,” of “The Empathy Game,” were used to help understand what is truly needed in a kind and caring school environment. -

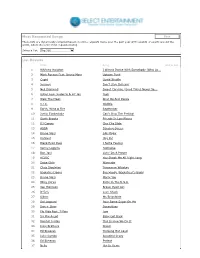

Most Requested Songs List Results

Most Requested Songs Back These lists are dynamically compiled based on online requests made over the past year at thousands of events around the world, where #1 is the most requested song. Select a List: Top 200 List Results Artist Song Add to List 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Lo... 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 4 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Se... 6 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 7 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 8 V.I.C. Wobble 9 Earth, Wind & Fire September 10 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 11 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 ABBA Dancing Queen 14 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 15 Outkast Hey Ya! 16 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 17 Kenny Loggins Footloose 18 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Spice Girls Wannabe 21 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 22 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 23 Bruno Mars Marry You 24 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 25 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 26 B-52's Love Shack 27 Killers Mr. Brightside 28 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 29 Dan + Shay Speechless 30 Flo Rida Feat. T-Pain Low 31 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 32 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 33 Isley Brothers Shout 34 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 35 Luke Combs Beautiful Crazy 36 Ed Sheeran Perfect 37 Nelly Hot In Herre Artist Song Add to List 38 Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Ain't No Mountain High Enough 39 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 40 'N Sync Bye Bye Bye 41 Lil Nas X Feat. -

Grüße an A-Ha / Greetings to A-Ha Birgit Alias Beatchy 22.Aug.2002 16

Greetings & Congratulations to / Grüße & Glückwünsche an a-ha!!! Grüße an a-ha / Greetings to a-ha 22.Aug.2002 Birgit alias Beatchy 16:20 Hallo, hier kannst Du Deine ganz persönlichen Grüße an a-ha schreiben! Die Grüße an die gesamte Band werden auch an Morten übergeben! Tschüss Birgit alias Beatchy [email protected] Hello, here you can write your personal greetings to a-ha. The greetings for the whole band will be handed to Morten as well. Bye Birgit alias Beatchy [email protected] HomePage www.a-ha4ever.com RE: Grüße an a-ha / Greetings to a-ha 22.Aug.2002 Russ Gudz ; [email protected] 16:21 Hey Guys! I just wanted to tell you how much I really appreciate your music. Love the New CD..I wish that you'd consider doing a U.S. tour. Get that record company of yours to start doing some promos in the U.S. and we'll all be happy. I'm doing the best that i can to promote The band on my own here in Atlanta,Ga,U.S.A. But I can't do it alone. I write stories about the band and they can be viewed at http://www.cdd.ee/ in the funny stuff section. The Cold as Stone website.. Happy birthday!!... Fan for life,Russ HomePage http://www.cdd.ee : The Cold as Stone website RE: Grüße an a-ha / Greetings to a-ha 22.Aug.2002 Blue ; [email protected] 16:56 Keep on doing your great job - your music was, is and will always be very special. -

Live Band Karaoke Song List 2017

Live Band Karaoke Song List 2017 50s, 60s & 70s Pop/Rock A Hard Day’s Night – The Beatles All Day And All Of The Night – The Kinks American Woman – The Guess Who Back In The USSR – The Beatles Bad Moon Rising – CCR Bang A Gong – T. Rex Barracuda – Heart Be My Baby – The Ronettes Beast Of Burden – Rolling Stones Birthday – The Beatles Black Dog – Led Zeppelin Born To Be Wild – Steppenwolf Born to Run – Bruce Springsteen Break On Through – The Doors California Dreaming – Mamas & The Papas Come Together – The Beatles Communication Breakdown – Led Zeppelin Crazy Little Thing Called Love – Queen Dead Flowers – The Rolling Stones Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood – The Animals Don’t Let Me Down – The Beatles Dream On – Aerosmith D’yer Mak’er – Led Zeppelin Fat Bottom Girls – Queen Funk #49 – James Gang Get Back – The Beatles Good Times and Bad Times – Led Zeppelin Happy Together – The Turtles Heartbreaker/ Living Loving Maid – Led Zeppelin Helter Skelter – The Beatles Hey Joe – Jimi Hendrix Hit Me With Your Best Shot – Pat Benatar Hold On Loosely – .38 Special Hound Dog – Elvis Presley House Of The Rising Sun – The Animals I Got You Babe – Sonny and Cher Immigrant Song – Led Zeppelin Into the Mystic – Van Morrison Jumpin’ Jack Flash – The Rolling Stones Lights – Journey Manic Depression – Jimi Hendrix Mony Mony – Tommy James and the Shondells More Than A Feeling – Boston Oh! Darling – The Beatles Paint It Black – Rolling Stones Peggy Sue – Buddy Holly Purple Haze – Jimi Hendrix Revolution – The Beatles Rock and Roll – Led Zeppelin Rock And Roll -

Steve's Karaoke Songbook

Steve's Karaoke Songbook Artist Song Title Artist Song Title +44 WHEN YOUR HEART STOPS INVISIBLE MAN BEATING WAY YOU WANT ME TO, THE 10 YEARS WASTELAND A*TEENS BOUNCING OFF THE CEILING 10,000 MANIACS CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE MORE THAN THIS AALIYAH ONE I GAVE MY HEART TO, THE THESE ARE THE DAYS TRY AGAIN TROUBLE ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN 10CC THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE FERNANDO 112 PEACHES & CREAM GIMME GIMME GIMME 2 LIVE CREW DO WAH DIDDY DIDDY I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO ME SO HORNY I HAVE A DREAM WE WANT SOME PUSSY KNOWING ME, KNOWING YOU 2 PAC UNTIL THE END OF TIME LAY ALL YOUR LOVE ON ME 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME MAMMA MIA 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS DO FOR LOVE SOS 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE SUPER TROUPER 3 DOORS DOWN BEHIND THOSE EYES TAKE A CHANCE ON ME HERE WITHOUT YOU THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC KRYPTONITE WATERLOO LIVE FOR TODAY ABBOTT, GREGORY SHAKE YOU DOWN LOSER ABC POISON ARROW ROAD I'M ON, THE ABDUL, PAULA BLOWING KISSES IN THE WIND WHEN I'M GONE COLD HEARTED 311 ALL MIXED UP FOREVER YOUR GIRL DON'T TREAD ON ME KNOCKED OUT DOWN NEXT TO YOU LOVE SONG OPPOSITES ATTRACT 38 SPECIAL CAUGHT UP IN YOU RUSH RUSH HOLD ON LOOSELY STATE OF ATTRACTION ROCKIN' INTO THE NIGHT STRAIGHT UP SECOND CHANCE WAY THAT YOU LOVE ME, THE TEACHER, TEACHER (IT'S JUST) WILD-EYED SOUTHERN BOYS AC/DC BACK IN BLACK 3T TEASE ME BIG BALLS 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP 50 CENT AMUSEMENT PARK FOR THOSE ABOUT TO ROCK (WE SALUTE YOU) CANDY SHOP GIRLS GOT RHYTHM DISCO INFERNO HAVE A DRINK ON ME I GET MONEY HELLS BELLS IN DA -

1 Nr Artiest Titel

NR ARTIEST TITEL 1 PRINCE & THE REVOLUTION PURPLE RAIN 2 MICHAEL JACKSON THRILLER 3 QUEEN & DAVID BOWIE UNDER PRESSURE 4 TOTO AFRICA 5 GUNS N' ROSES SWEET CHILD OF MINE 6 A-HA TAKE ON ME 7 U2 SUNDAY BLOODY SUNDAY 8 PHIL COLLINS IN THE AIR TONIGHT 9 JOURNEY DON'T STOP BELIEVIN' 10 DURAN DURAN THE REFLEX 11 BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN BORN IN THE USA 12 QUEEN A KIND OF MAGIC 13 GUNS N' ROSES PARADISE CITY 14 ALAN PARSONS PROJECT OLD AND WISE 15 THE CURE A FOREST 16 EUROPE THE FINAL COUNTDOWN 17 BON JOVI LIVIN' ON A PRAYER 18 ANDRÉ HAZES ZIJ GELOOFT IN MIJ 19 QUEEN RADIO GA GA 20 MADONNA LIKE A PRAYER 21 PINK FLOYD ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL 22 ABBA THE WINNER TAKES IT ALL 23 MICHAEL JACKSON BILLIE JEAN 24 ALICE COOPER POISON 25 PAUL SIMON YOU CAN CALL ME AL 26 QUEEN I WANT TO BREAK FREE 27 U2 WITH OR WITHOUT YOU 28 ACDC BACK IN BLACK 29 THE POLICE EVERY LITTLE THING SHE DOES IS MAGIC 30 DIRE STRAITS BROTHERS IN ARMS 31 ROLLING STONES START ME UP 32 TALK TALK SUCH A SHAME 33 GEORGE MICHAEL FAITH 1 NR ARTIEST TITEL 34 VANDENBERG BURNING HEART 35 DOE MAAR 32 JAAR (SINDS EEN DAG OF 2) 36 AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR 37 ANITA MEYER WHY TELL ME WHY 38 SIMPLE MINDS DON'T YOU (FORGET ABOUT ME) 39 BILLY OCEAN WHEN THE GOING GETS TOUGH, THE TOUGH GETS GOING 40 VAN HALEN JUMP 41 U2 PRIDE (IN THE NAME OF LOVE) 42 ABC THE LOOK OF LOVE 43 SURVIVOR EYE OF THE TIGER 44 TOTO STOP LOVING YOU 45 SALT-N-PEPA PUSH IT 46 KLEIN ORKEST OVER DE MUUR 47 ZZ TOP GIMME ALL YOUR LOVIN' 48 MICHAEL JACKSON SMOOTH CRIMINAL 49 DIRE STRAITS PRIVATE INVESTIGATIONS 50 PAT BENATAR LOVE -

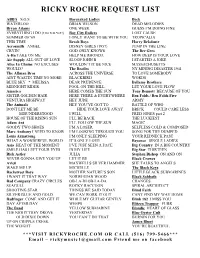

Ricky Roche Request List

RICKY ROCHE REQUEST LIST ABBA S.O.S. Barenaked Ladies Beck WATERLOO BRIAN WILSON DEAD MELODIES Bryan Adams ONE WEEK GUESS I’M DOING FINE EVERYTHING I DO (I DO FOR YOU) Bay City Rollers LOST CAUSE SUMMER OF '69 I ONLY WANT TO BE WITH YOU TROPICALIA THIS TIME Beach Boys Harry Belafonte Aerosmith ANGEL DISNEY GIRLS (1957) JUMP IN THE LINE CRYIN’ GOD ONLY KNOWS The Bee Gees A-Ha TAKE ON ME HELP ME RHONDA HOW DEEP IS YOUR LOVE Air Supply ALL OUT OF LOVE SLOOP JOHN B I STARTED A JOKE Alice In Chains NO EXCUSES WOULDN’T IT BE NICE MASSACHUSETTS WOULD? The Beatles NY MINING DISASTER 1941 The Allman Bros ACROSS THE UNIVERSE TO LOVE SOMEBODY AINT WASTIN TIME NO MORE BLACKBIRD WORDS BLUE SKY * MELISSA DEAR PRUDENCE Bellamy Brothers MIDNIGHT RIDER FOOL ON THE HILL LET YOUR LOVE FLOW America HERE COMES THE SUN Tony Bennett BECAUSE OF YOU SISTER GOLDEN HAIR HERE THERE & EVERYWHERE Ben Folds / Ben Folds Five VENTURA HIGHWAY HEY JUDE ARMY The Animals HEY YOU’VE GOT TO BATTLE OF WHO DONT LET ME BE HIDE YOUR LOVE AWAY BRICK COULD CARE LESS MISUNDERSTOOD I WILL FRED JONES part 2 HOUSE OF THE RISING SUN I’LL BE BACK THE LUCKIEST Adam Ant I’LL FOLLOW THE SUN MAGIC GOODY TWO SHOES I’M A LOSER SELFLESS COLD & COMPOSED Marc Anthony I NEED TO KNOW I’M LOOKING THROUGH YOU SONG FOR THE DUMPED Louis Armstrong I’M ONLY SLEEPING YOUR REDNECK PAST WHAT A WONDERFUL WORLD IT’S ONLY LOVE Beyonce SINGLE LADIES Asia HEAT OF THE MOMENT I’VE JUST SEEN A FACE Big Country IN A BIG COUNTRY SMILE HAS LEFT YOUR EYES IN MY LIFE Big Star THIRTEEN Rick Astley JULIA Stephen Bishop -

Chapter 4: A-Ha's "Take on Me" and Postmodern Metamorphoses

CHAPTER 4: A-HA'S "TAKE ON ME" AND POSTMODERN METAMORPHOSES Historically there has been a great deal of confusion between metafiction and postmodernism. Metafiction, or fiction that is about fiction, is not at all a new development in literature. Authors have been using metafiction for centuries. In other words, postmodernists’ use of metafiction is a “continuation of an already existing narcissistic trend in the novel as it began parodically in Don Quijote and was handed on, through eighteenth-century critical self-awareness to nineteenth-century self-mirroring” (Hutcheon, 1980, 153). Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy and Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author are other examples of metafictive works that are by no means postmodern. They predate postmodernism. Hence, the simple presence of metafiction in a text does not make the text postmodern. Postmodernists distinguish themselves from their predecessors not by using metafiction per se but by the way in which they use metafiction. Postmodernists use metafiction to explore ontological issues. Each of the five novels I consider in this project is indisputably metafictive. What is more noteworthy, however, is the repeated pattern of metamorphosis that consistently emerges through the authors’ use of metafiction. In this chapter I will show that postmodernist metamorphosis reliably breaks down into four characteristic features: the description of two ontologically distinct worlds, frequent transgressions of the membrane between the two worlds, resistance to permeating the membrane between the two worlds, and a major instance of metalepsis in which a character or narrator permanently transcends the membrane. Conveniently, the Norwegian band A-ha’s 1985 video “Take on Me” demonstrates precisely these same four features of postmodern metamorphosis. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun