A Qualitative Assessment of the Pedagogical Process at Czech Public Universities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report on the Activities of the Brno University of Technology in 2016 Annual Report on the Activities of the Brno University of Technology in 2016

ANNUAL REPORT ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE BRNO UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY IN 2016 ANNUAL REPORT ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE BRNO UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY IN 2016 Annual Report on the Activities of Brno University of Technology in 2016 The Annual Report on the Activities of Brno University of Technology for the year 2016 is presented in accordance with law no. 111/1998 Coll., on universities. It has been elaborated according to the framework curriculum of the university activities for the year 2016 issued by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic. Newly, the document is divided into a text and table part with a fi xed structure based on the framework curriculum. On the other hand, the introductory part remains entirely in the management of the University and presents the information beyond the required curriculum. This all has been elaborated in accordance with the instructions of the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic. The Annual Report off ers the data and substantial results of all activities related to the mission of Brno University of Technology in the scope of both Czech and international post-secondary education and off ers the general public an overview of the university’s major scientifi c and research activities. The Annual Report was approved by the Academic Senate of BUT on 2nd May 2017. ISBN 978-80-214-5483-5 CONTENT 1 Introduction 6 10 Quality assurance and evaluation of activities 58 1.1 Introductory words of the rector 7 10.1 Signifi cant events related to quality assurance and evaluation -

Healthcom 2018)

2018 IEEE 20th International Conference on e-Health Networking, Applications and Services (Healthcom 2018) Ostrava, Czech Republic 17-20 September 2015 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP18545-POD ISBN: 978-1-5386-4295-5 Copyright © 2018 by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc. All Rights Reserved Copyright and Reprint Permissions: Abstracting is permitted with credit to the source. Libraries are permitted to photocopy beyond the limit of U.S. copyright law for private use of patrons those articles in this volume that carry a code at the bottom of the first page, provided the per-copy fee indicated in the code is paid through Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923. For other copying, reprint or republication permission, write to IEEE Copyrights Manager, IEEE Service Center, 445 Hoes Lane, Piscataway, NJ 08854. All rights reserved. *** This is a print representation of what appears in the IEEE Digital Library. Some format issues inherent in the e-media version may also appear in this print version. IEEE Catalog Number: CFP18545-POD ISBN (Print-On-Demand): 978-1-5386-4295-5 ISBN (Online): 978-1-5386-4294-8 Additional Copies of This Publication Are Available From: Curran Associates, Inc 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 USA Phone: (845) 758-0400 Fax: (845) 758-2633 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.proceedings.com 2018 IEEE 20th International Conference on e-Health Networking, Applications and Services (Healthcom) IOT-HEALTH 2018 and ETPHA 2018 Workshops VITASENIOR-MT: a telehealth solution -

Pädagogische Hochschule Viktor Frankl Hochschule Austria The

Pädagogische Hochschule Viktor Frankl Hochschule Austria The Private University College of Education of the Diocese of Linz Austria Vienna University of Teacher Education Austria Belarus State Pedagogical University 'M. Tank' Belarus Catholic College, Louvain Belgium Haute École de Namur-Liège-Luxembourg Belgium Charles University, Prague Czech Republic 'J.E. Purkynì' University in òstí nad Labem Czech Republic Palacky University, Olomouc Czech Republic Technical University of Ostrava Czech Republic University of Hradec Králové Czech Republic Bornholms Sundheds- og Sygeplejeskole Denmark Copenhagen Business School Denmark Metropolitan University College Denmark Professionshøjskolen UCC Denmark Roskilde University Denmark University College Absalon Denmark University College Lillebælt Denmark University College South Denmark Denmark VIA University College Denmark Sjúkrarøktarfrødiskúli Føroya Faroe Islands Humak University of Applied Sciences Finland Kemi-Tornio Polytechnic Finland Laurea University of Applied Sciences Finland Saimaa University of Applied Sciences Finland Turku University of Applied Sciences Finland University of Eastern Finland Finland University of Lapland Finland University of Tampere Finland Vaasa Polytechnic Finland Yrkeshögskolan Novia Finland KEDGE Business School France Normandy Business School France University François Rabelais of Tours France University Jean Monnet Saint-Etienne France University of Burgundy, Dijon France University of Caen France University Paris Descartes (Paris V) France Albert Ludwig University -

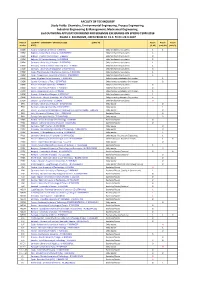

FACULTY of TECHNOLOGY Study Fields: Chemistry, Environmental Engineering, Process Engineering, Industrial Engineering & Management, Mechanical Engineering

FACULTY OF TECHNOLOGY Study Fields: Chemistry, Environmental Engineering, Process Engineering, Industrial Engineering & Management, Mechanical Engineering. 2nd OUTGOING APPLICATION ROUND FOR ERASMUS EXCHANGES ON SPRING TERM 2018 PHASE 1: SOLEMOVE, OPEN FROM Fri 15.9. TO Fri 29.9.2017 Field of COUNTRY - UNIVERSITY - ERASMUS CODE (LINKS TO Places Places Places studies HOST) (B, M) (only M) (only D) CHEM Austria - University of Vienna - A WIEN01 Only for chemistry students 1 1 CHEM Belgium - University of Antwerp - B ANTWERP01 Only for chemistry students 1 CHEM Belgium - Thomas More Kempen - B GEEL07 Only for chemistry students 2 CHEM Belgium - UC Leuven-Limburg - B LEUVEN18 Only for chemistry students 2 CHEM Germany - University of Bremen - D BREMEN01 Only for chemistry students 1 CHEM Germany - Friedrich Schiller University Jena - D JENA01 Only for chemistry students 1 CHEM Germany - University of Wuppertal - D WUPPERT01 Only for chemistry students 3 CHEM Spain - The University of the Basque Country - E BILBAO01 Only for chemistry students 1 CHEM Spain - Complutense University of Madrid - E MADRID03 Only for chemistry students 1 CHEM Spain - King Juan Carlos University - E MADRID26 Only chemistry students. Only master. 1 CHEM Estonia - University of Tartu - EE TARTU02 Only chemistry students. Only master. 2 CHEM France - Paris-Sud University - F PARIS011 Only for chemistry students 2 CHEM France - University of Poitiers - F POITIER01 Only for chemistry students 2 CHEM Latvia - University of Latvia - LV RIGA01 Only chemistry students. Only master. 1 CHEM Norway - University of Bergen - N BERGEN01 Only for chemistry students 1 CHEM Netherlands - Utrecht University - NL UTRECHT01 Only chemistry students. Only master. 1 CHEM Sweden - Lund University - S LUND01 Only for chemistry students 0 ENV Germany - University of Rostock - D ROSTOCK01 Only master. -

Czech Republic Psychology

QS World University Rankings by Subject 2016 COUNTRY FILE v1.0 Subject Influence Map ■ Arts & Humanities ■ Engineering & Technology ■ Life Sciences & Medicine ARCHAEOLOGY ■ Natural Sciences ■ Social Sciences & Management % Institutions Ranked in Subject % Institutions Scored in Subject CZECH REPUBLIC PSYCHOLOGY Overall Country Performance Institutions cited by academics in at least one subject 21 Subjects featuring at least one institution from Czech Republic 19 Institutions ranked in at least one subject 18 Institutions in published ranking for at least one subject 7 Range Representation by Subject The following tables display the number of institutions from Czech Republic featured in each subject within each given range. Please note that different numbers of institutions are presented overall in different subjects - ranges shaded in grey do not exist for the subjects in question ARTS & HUMANITIES ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY Top 50 51-100 101-150 151-200 201-250 251-300 301-350 351-400 Top 50 51-100 101-150 151-200 201-250 251-300 301-350 351-400 Archaeology 0 0 Computer Science & Information Systems 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 Architecture / Built Environment 0 0 Engineering - Chemical 0 0 0 0 Art & Design 0 0 Engineering - Civil & Structural 0 1 0 1 English Language & Literature 0 0 0 1 0 0 Engineering - Electrical & Electronic 0 0 0 1 1 0 History 0 0 0 1 Engineering - Mechanical, Aeronautical & Manufacturing 0 0 0 1 0 1 Linguistics 0 0 0 1 Engineering - Mineral & Mining 0 0 Modern Languages 0 0 1 0 0 0 Performing Arts 0 1 LIFE SCIENCES & MEDICINE -

OECD LEED REVIEWS Universities, Entrepreneurship and Local Development

OECD LEED REVIEWS Universities, Entrepreneurship and Local Development MORAVIA-SILESIA, CZECH REPUBLIC ENHANCING THE LOCAL DEVELOPMENT CONTRIBUTIONS OF HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS 1 IN COLLABORATION WITH MINISTRY OF EDUCATION, YOUTH AND SPORTS OF THE CZECH REPUBLIC 2 Source cover picture: City Council of Ostrava Design: Joseph Tixier, OECD OECD LEED REVIEWS ON UNIVERSITIES, ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT ENHANCING THE LOCAL DEVELOPMENT CONTRIBUTIONS OF HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS IN MORAVIA-SILESIA, CZECH REPUBLIC" REVIEW REPORT AUGUST 2014 3 Acknowledgements This review of the contributions of higher education institutions to local development in the Moravia-Silesia region in Czech Republic would not have been possible without the contributions, commitments and dedication of many people. The authors firstly thank the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic, who requested Local Economic and Employment Development Programme (LEED) of the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development to undertake this review. Petr Černikovský and Kristýna Žůrková, accompanied the entire review process, and provided invaluable support. The authors are also grateful to the higher education institutions in Moravia-Silesia, the local authorities and a wide range of local development stakeholders at regional and municipal levels for their interest in the review and their engagement in the organisation of the study visit and the regional workshop. Special thanks are extended to the translators and interpreters! Jaana Puukka, former OECD analyst, has played a crucial role in getting this review started. She was part of the international review team as core expert and prepared the chapter on the policy framework and institutional level impacts as well as the draft version of this report. -

Brno University of Technology Annual Report 2013

BRNO UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY BRNO UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY ANNUAL REPORT 2013 2013 ANNUAL REPORT 1 BRNO UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY 2013 ANNUAL REPORT is submitted as required by Act no. 111/1998 Coll. concerning universities. It was made according to the university activity guidelines for 2013 published by the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports. To a wider public, it presents data and major results of all the activities related to Brno University of Technology as part of the Czech and international higher education system, research and social activities. ISBN 978-80-214-4928-2 TabLE OF CONTENTS 01 INTRODUCTION 004 Rector‘s Word 005 Significant Events 006 Major Projects 012 02 BASIC DATA 020 a) Full name of the public higher-education institution, acronym used, addresses of all its parts 021 b) BUT Organizational Chart 021 c) BUT Scientific Board, Managerial Board, Academic Senate 022 d) BUT representatives in the representation of universities 024 e) Nature of BUT mission, vision, and strategic goals 024 f) Amendments to BUT internal regulations in 2013 025 g) Providing information under Act no. 106/1999 Coll., concerning free access to information 026 03 DEGREE PROGRAMMES, STUDY ORGANISATION, AND EDUCATION 028 a) Accredited degree programmes (numbers in master groups according to study type and form) listed by faculty or other constituent parts offering an accredited degree programme or its part 029 b) Degree programmes taught in a foreign language by faculties or other constituent parts offering an accredited programme or part -

UNIVERSITY of OSTRAVA Department of Human Geography and Regional Development

UNIVERSITY OF OSTRAVA Department of Human Geography and Regional Development CONFERENCE MIGRATION AND DEVELOPMENT held in Ostrava on September 4th - 5th, 2007 The conference is supported by the European Social Fund PROGRAMME SCIENTIFIC BOARD CHAIRMAN Prof. Janos J. BOGARDI, Director of Institute for Environment and Human Security (UNU-EHS), United Nations University, Bonn, Germany BOARD MEMBERS AND KEY SPEAKERS Prof. Ronald SKELDON, Department of Geography, School of Social and Cultural Studies, University of Sussex, United Kingdom Prof. Graeme HUGO, Department of Geographical and Environmental Studies, The University of Adelaide, Australia Assoc. Prof. Dušan DRBOHLAV, Department of Social Geography and Regional Development, Faculty of Science, Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic Prof. J.A.(Tony) BINNS, Ron Lister Chair of Geography, Department of Geography, University of Otago, New Zealand Assoc. Prof. Jan KLÍMA, Cabinet of Iberoamerican Studies, Faculty of Humanities, University of Hradec Králové, Czech Republic Prof. Oscar Alvarez GILA, Facultad de Filología, Geografía e Historia, Universidad del País Vasco/University of the Basque Country, Spain Assoc. Prof. Tadeusz SIWEK, President of the Czech Geographical Union Department of Human Geography and Regional Development, Faculty of Science, University of Ostrava, Czech Republic François GEMENNE, M.A. et M.Res., Centre d'Etudes de l'Ethnicité et des Migrations (CEDEM), Université de Li`ege, Belgium; Centre d'Etudes et de Recherches Internationales (CERI), Institut d'Etudes Politiques -

List of Erasmus+ Partner Institutions

List of Erasmus+ Partner Institutions LJMU School/Programme Partner Institution Art and Design Iceland Academy of Arts L' INSTITUT SUPERIEUR DES ARTS APPLIQUES Hochschule der Bildenden Kunste Saar Pecsi Tudomanyegyetem Marseille-Mediterranea College of Arts and Design Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam FH Joanneum - University of Applied Sciences Built Environment Danmarks Tekniske Universitet University Miskolc Middle East Technical University Anadalou Universitesi Istanbul Technical University University of Ostrava Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universitat Bonn Kauno Technologijos Universitetas Aleksandras Stulginskis University Vilnius Gediminas Technical University Latvia University of Agriculture Via University College Universidad de Oviedo Civil Engineering and Engineering Universidad de Oviedo and Technology Computer Science Hogeschool Gent Istanbul Technical University Education Tallinn University Universitat Rovira I Virgili Universitatea Babes-Bolyai, Cluj-Napcoa University of Gothenburg University of Eastern Finland Roskilde University Universitat Oldenburg University of Sassari University of Vic Engineering University College of Southeast Norway University of Balekesir KTH Royal Institute of Technology Angel Kunchev University of Rousse Gaziantep Universitesi Universitatea Politehnica Din Bucuresti Istanbul Technical University Humanities and Social Science Szegedi Tudomanyegyetem De Haagse Hogeschool Tischner European University/Wyzsza Szkola Europejsra Im. Ks. Jozefa Tischnera Universita' degli Studi di Napoli "L 'Orientale" University -

European Partner Universities to University of Southern Denmark

European partner universities to University of Southern Denmark Austria FH Joanneum FHS Kufstein Tirol University of Applied Sciences Graz University of Technology Management Center Innsbruck MODUL University Vienna Salzburg University of Applied Sciences University of Applied Sciences Technikum Wien University of Applied Sciences Upper Austria University of Applied Sciences Wiener Neustadt University of Graz University of Vienna Belgium Ghent University Hasselt University ICHEC Brussels Management School KU Leuven Université Catholique de Louvain University College Gent Bulgaria Sofia University 'Saint Kliment Ohridski' Technical University of Sofia Croatia University of Zadar Cypern University of Cyprus Czech Republic Brno University of Technology Charles University in Prague Czech Technical University in Prague Czech University of Life Sciences Prague Masaryk University Metropolitan University Prague University of Economics, Prague University of Palacky University of Pardubice University of West Bohemia VSB - Technical University of Ostrava Denmark University of Greenland University of the Faroe Islands Estonia Tallinn University of Applied Sciences (TTK) Tallinn University of Technology University of Tartu Finland Hanken School of Economics Lappeenranta University of Technology Oulu University of Applied Sciences South-Eastern Finland University of Applied Sciences Tampere University of Applied Sciences (TAMK) Tampere University of Technology University of Eastern Finland University of Helsinki University of Jyväskylä University of -

Proceedings of the Dateso 2015 Workshop

Charles University in Prague, MFF, Department of Software Engineering Czech Technical University in Prague, FIT, Dept. of Software Engineering VSB{TUˇ Ostrava, FEECS, Department of Computer Science Czech Society for Cybernetics and Informatics Proceedings of the Dateso 2015 Workshop Databases, Texts Specifications, and Objects 2015 http://www.cs.vsb.cz/dateso/2015/ http://www.ceur-ws.org/Vol-1343/ April 14 { 16, 2015 Nepˇr´ıvˇecu Sobotky, Jiˇc´ın,Czech Republic DATESO 2015 c M. Neˇcask´y,J. Pokorn´y,P. Moravec, editors This work is subject to copyright. All rights reserved. Reproduction or publication of this material, even partial, is allowed only with the editors' permission. Technical editor: Pavel Moravec, [email protected] VSBˇ { Technical University of Ostrava Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Department of Computer Science Page count: 141 Edition: 1st First published: 2015 This proceedings was typeset by PDFLATEX. Cover design by Pavel Moravec ([email protected]) and Tom´aˇsSkopal. Originally published under ISBN 978-80-7378-285-6 by MATFYZPRESS publishing house of Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Charles University, Sokolovsk´a83, 186 75 Praha 8 { Karl´ın,Czech Republic as its 479th publication. Steering Committee V´aclav Sn´aˇsel VSB-Technicalˇ University of Ostrava, Ostrava Karel Richta Czech Technical University, Prague Jaroslav Pokorn´y Charles University, Prague Program Committee Martin Neˇcask´y(chair) Charles University, Prague Wolfgang Benn Technische Universit¨atChemnitz, Chemnitz, Germany V´aclav Sn´aˇsel VSB-Technicalˇ University of Ostrava, Ostrava Jaroslav Pokorn´y Charles University, Prague Karel Richta Czech Technical University, Prague Michal Valenta Czech Technical University, Prague Vojtˇech Sv´atek University of Economics, Prague Peter Vojt´aˇs Charles University, Prague DuˇsanH´usek Inst. -

Conference Program

2DMAT2021 Global Summit and Expo on Graphene and 2D Materials August 23-25, 2021 Paris, France TENTATIVE PROGRAM The Scientistt Bangalore, India Contact: +91 77 99 83 5553 Email: [email protected] Monday, August-23, 2021 09:00-09:20 Registrations 09:20-09:30 Opening Cermony Plenary Session Title: Twistronics Of 2D Transition Metal Dichalcogenides 09:30-10:10 P Vladimir Falko, University of Manchester, UK Title: Covalent Functionalization of Graphene for Applications in 10:10-10:50 Magnetism, Biomedicine, Catalysis, and Environmental Technologies P R. Zbořil, VŠB–Technical University of Ostrava, Czech Republic Keynote Session Title: Self-adaptive 2D Membranes 10:50-11:20 K Daria Andreeva, National University of Singapore, Singapore 11:20-11:35 Coffee Break Title: Print-in-Place and Recyclable Electronics Using Mixed- 11:35-12:05 Dimensional Nanomaterials K Aaron D. Franklin, Duke University, USA Title: The Road from Semiconductors to Metals: Engineering 12:05-12:35 Topological States in Nanographene K F. R. Fischer, University of California Berkeley, USA Title: Exploring Potential of Functionalized Graphene and Free- Standing Graphene Membranes 12:35-13:05 K M. Kalbac, Heyrovsky Institute of Physical Chemistry of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Czech Republic 13:05-13:15 Group Photo 13:15-14:05 Lunch Break Title: Optically-Active, Vapor-Deposited and Solution-Processed Two-Dimensional Van Der Waals Solids and Perovskites for 14:05-14:35 Nanodevices K Anupama B Kaul, University of North Texas, USA Title: Devices with “Zero D” holes