OECD LEED REVIEWS Universities, Entrepreneurship and Local Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report on the Activities of the Brno University of Technology in 2016 Annual Report on the Activities of the Brno University of Technology in 2016

ANNUAL REPORT ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE BRNO UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY IN 2016 ANNUAL REPORT ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE BRNO UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY IN 2016 Annual Report on the Activities of Brno University of Technology in 2016 The Annual Report on the Activities of Brno University of Technology for the year 2016 is presented in accordance with law no. 111/1998 Coll., on universities. It has been elaborated according to the framework curriculum of the university activities for the year 2016 issued by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic. Newly, the document is divided into a text and table part with a fi xed structure based on the framework curriculum. On the other hand, the introductory part remains entirely in the management of the University and presents the information beyond the required curriculum. This all has been elaborated in accordance with the instructions of the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic. The Annual Report off ers the data and substantial results of all activities related to the mission of Brno University of Technology in the scope of both Czech and international post-secondary education and off ers the general public an overview of the university’s major scientifi c and research activities. The Annual Report was approved by the Academic Senate of BUT on 2nd May 2017. ISBN 978-80-214-5483-5 CONTENT 1 Introduction 6 10 Quality assurance and evaluation of activities 58 1.1 Introductory words of the rector 7 10.1 Signifi cant events related to quality assurance and evaluation -

Environmental & Socio-Economic Studies

Environmental & Socio-economic Studies DOI: 10.1515/environ-2015-0044 Environ. Socio.-econ. Stud., 2014, 2, 4: 1-12 © 2014 Copyright by University of Silesia ________________________________________________________________________________________________ Reclamation of devastated landscape in the Karviná region (Czech Republic) Jan Havrlant, Ludĕk Krtička Department of Social Geography and Regional Development, Faculty of Science, University of Ostrava, Chittussiho Str. 10, 710 00 Ostrava, Czech Republic E–mail address: [email protected] ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT The article deals with the recent positive changes in the industrial landscape of the Karviná region in a broader context. The Karviná region has been the most important part of the coal-bearing Ostrava-Karviná District. Since the industrial revolution, the position of the primary mining area has brought a dynamic economic development and a great concentration of population into the fast-growing conurbation cities, particularly between 1950s and 1980s. However, the dominant coal mining and processing has had a negative impact on the environment, the character and utilization of the landscape. Many environmental, socioeconomic and other problems did not become fully evident until the social changes at the turn of 1980s and 1990s. At present, a great attention is being paid to the reclamation of the affected landscape. As a result, the region is starting to change its unflattering image of an industrial and problematic area devastated by coal extraction for the better after many years. The various forms of land reclamation, modification of water bodies, construction of new sports and recreational facilities and so on are bringing a gradual improvement of the environment in the region, creating a new cultivated landscape that can be used, among other things, for various forms of tourism and relaxation. -

Healthcom 2018)

2018 IEEE 20th International Conference on e-Health Networking, Applications and Services (Healthcom 2018) Ostrava, Czech Republic 17-20 September 2015 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP18545-POD ISBN: 978-1-5386-4295-5 Copyright © 2018 by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc. All Rights Reserved Copyright and Reprint Permissions: Abstracting is permitted with credit to the source. Libraries are permitted to photocopy beyond the limit of U.S. copyright law for private use of patrons those articles in this volume that carry a code at the bottom of the first page, provided the per-copy fee indicated in the code is paid through Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923. For other copying, reprint or republication permission, write to IEEE Copyrights Manager, IEEE Service Center, 445 Hoes Lane, Piscataway, NJ 08854. All rights reserved. *** This is a print representation of what appears in the IEEE Digital Library. Some format issues inherent in the e-media version may also appear in this print version. IEEE Catalog Number: CFP18545-POD ISBN (Print-On-Demand): 978-1-5386-4295-5 ISBN (Online): 978-1-5386-4294-8 Additional Copies of This Publication Are Available From: Curran Associates, Inc 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 USA Phone: (845) 758-0400 Fax: (845) 758-2633 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.proceedings.com 2018 IEEE 20th International Conference on e-Health Networking, Applications and Services (Healthcom) IOT-HEALTH 2018 and ETPHA 2018 Workshops VITASENIOR-MT: a telehealth solution -

Pädagogische Hochschule Viktor Frankl Hochschule Austria The

Pädagogische Hochschule Viktor Frankl Hochschule Austria The Private University College of Education of the Diocese of Linz Austria Vienna University of Teacher Education Austria Belarus State Pedagogical University 'M. Tank' Belarus Catholic College, Louvain Belgium Haute École de Namur-Liège-Luxembourg Belgium Charles University, Prague Czech Republic 'J.E. Purkynì' University in òstí nad Labem Czech Republic Palacky University, Olomouc Czech Republic Technical University of Ostrava Czech Republic University of Hradec Králové Czech Republic Bornholms Sundheds- og Sygeplejeskole Denmark Copenhagen Business School Denmark Metropolitan University College Denmark Professionshøjskolen UCC Denmark Roskilde University Denmark University College Absalon Denmark University College Lillebælt Denmark University College South Denmark Denmark VIA University College Denmark Sjúkrarøktarfrødiskúli Føroya Faroe Islands Humak University of Applied Sciences Finland Kemi-Tornio Polytechnic Finland Laurea University of Applied Sciences Finland Saimaa University of Applied Sciences Finland Turku University of Applied Sciences Finland University of Eastern Finland Finland University of Lapland Finland University of Tampere Finland Vaasa Polytechnic Finland Yrkeshögskolan Novia Finland KEDGE Business School France Normandy Business School France University François Rabelais of Tours France University Jean Monnet Saint-Etienne France University of Burgundy, Dijon France University of Caen France University Paris Descartes (Paris V) France Albert Ludwig University -

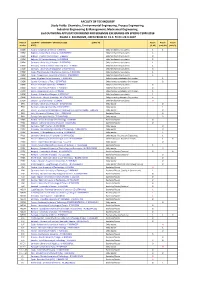

FACULTY of TECHNOLOGY Study Fields: Chemistry, Environmental Engineering, Process Engineering, Industrial Engineering & Management, Mechanical Engineering

FACULTY OF TECHNOLOGY Study Fields: Chemistry, Environmental Engineering, Process Engineering, Industrial Engineering & Management, Mechanical Engineering. 2nd OUTGOING APPLICATION ROUND FOR ERASMUS EXCHANGES ON SPRING TERM 2018 PHASE 1: SOLEMOVE, OPEN FROM Fri 15.9. TO Fri 29.9.2017 Field of COUNTRY - UNIVERSITY - ERASMUS CODE (LINKS TO Places Places Places studies HOST) (B, M) (only M) (only D) CHEM Austria - University of Vienna - A WIEN01 Only for chemistry students 1 1 CHEM Belgium - University of Antwerp - B ANTWERP01 Only for chemistry students 1 CHEM Belgium - Thomas More Kempen - B GEEL07 Only for chemistry students 2 CHEM Belgium - UC Leuven-Limburg - B LEUVEN18 Only for chemistry students 2 CHEM Germany - University of Bremen - D BREMEN01 Only for chemistry students 1 CHEM Germany - Friedrich Schiller University Jena - D JENA01 Only for chemistry students 1 CHEM Germany - University of Wuppertal - D WUPPERT01 Only for chemistry students 3 CHEM Spain - The University of the Basque Country - E BILBAO01 Only for chemistry students 1 CHEM Spain - Complutense University of Madrid - E MADRID03 Only for chemistry students 1 CHEM Spain - King Juan Carlos University - E MADRID26 Only chemistry students. Only master. 1 CHEM Estonia - University of Tartu - EE TARTU02 Only chemistry students. Only master. 2 CHEM France - Paris-Sud University - F PARIS011 Only for chemistry students 2 CHEM France - University of Poitiers - F POITIER01 Only for chemistry students 2 CHEM Latvia - University of Latvia - LV RIGA01 Only chemistry students. Only master. 1 CHEM Norway - University of Bergen - N BERGEN01 Only for chemistry students 1 CHEM Netherlands - Utrecht University - NL UTRECHT01 Only chemistry students. Only master. 1 CHEM Sweden - Lund University - S LUND01 Only for chemistry students 0 ENV Germany - University of Rostock - D ROSTOCK01 Only master. -

Czech Republic Psychology

QS World University Rankings by Subject 2016 COUNTRY FILE v1.0 Subject Influence Map ■ Arts & Humanities ■ Engineering & Technology ■ Life Sciences & Medicine ARCHAEOLOGY ■ Natural Sciences ■ Social Sciences & Management % Institutions Ranked in Subject % Institutions Scored in Subject CZECH REPUBLIC PSYCHOLOGY Overall Country Performance Institutions cited by academics in at least one subject 21 Subjects featuring at least one institution from Czech Republic 19 Institutions ranked in at least one subject 18 Institutions in published ranking for at least one subject 7 Range Representation by Subject The following tables display the number of institutions from Czech Republic featured in each subject within each given range. Please note that different numbers of institutions are presented overall in different subjects - ranges shaded in grey do not exist for the subjects in question ARTS & HUMANITIES ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY Top 50 51-100 101-150 151-200 201-250 251-300 301-350 351-400 Top 50 51-100 101-150 151-200 201-250 251-300 301-350 351-400 Archaeology 0 0 Computer Science & Information Systems 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 Architecture / Built Environment 0 0 Engineering - Chemical 0 0 0 0 Art & Design 0 0 Engineering - Civil & Structural 0 1 0 1 English Language & Literature 0 0 0 1 0 0 Engineering - Electrical & Electronic 0 0 0 1 1 0 History 0 0 0 1 Engineering - Mechanical, Aeronautical & Manufacturing 0 0 0 1 0 1 Linguistics 0 0 0 1 Engineering - Mineral & Mining 0 0 Modern Languages 0 0 1 0 0 0 Performing Arts 0 1 LIFE SCIENCES & MEDICINE -

The Mineral Industry of the Czech Republic in 2008

2008 Minerals Yearbook CZECH REPUBLIC U.S. Department of the Interior December 2010 U.S. Geological Survey THE MINERAL INDUS T RY OF T HE CZE C H REPUBLI C By Mark Brininstool The Czech Republic was an important Central European amended, establishes the rules for prospecting and exploration producer of heavy industrial goods manufactured by the of most mineral deposits. Act No. 61/1988 on Mining country’s chemical, machine building, and toolmaking Operations, Explosives and on the State Mining Administration, industries. The production of construction materials, the mining as amended, defines appropriate mining methods. The Ministry and processing of industrial minerals, and steelmaking were of the Environment enforces environmental laws in the mining of domestic and regional importance. The production of coal sector and has the authority to revoke exploration and mining for thermal powerplants and the use of nuclear power were leases if environmental laws are violated (Czech Geological important sources of electricity and helped the country maintain Survey, 2008, p. 25-26). a lower level of dependence on imported natural gas than many other Central European countries. Production Minerals in the National Economy For metals, crude steel and pig iron production each decreased by about 10% compared with production in 2007. Production of The Czech Republic’s gross domestic product (GDP) grew by industrial minerals increased significantly compared with that 2.5% in 2008, which was a significant decrease when compared of 2007 for diatomite (63%), glass sand (22%), and dolomite with the 6.1% growth recorded in 2007. Mining and quarrying (17%). Production decreased for bentonite (48%), gypsum and made up 1.5% of the total gross value added and about 1.4% of anhydrite (47%), sulfuric acid (22%), and foundry sand (17%). -

Brno University of Technology Annual Report 2013

BRNO UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY BRNO UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY ANNUAL REPORT 2013 2013 ANNUAL REPORT 1 BRNO UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY 2013 ANNUAL REPORT is submitted as required by Act no. 111/1998 Coll. concerning universities. It was made according to the university activity guidelines for 2013 published by the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports. To a wider public, it presents data and major results of all the activities related to Brno University of Technology as part of the Czech and international higher education system, research and social activities. ISBN 978-80-214-4928-2 TabLE OF CONTENTS 01 INTRODUCTION 004 Rector‘s Word 005 Significant Events 006 Major Projects 012 02 BASIC DATA 020 a) Full name of the public higher-education institution, acronym used, addresses of all its parts 021 b) BUT Organizational Chart 021 c) BUT Scientific Board, Managerial Board, Academic Senate 022 d) BUT representatives in the representation of universities 024 e) Nature of BUT mission, vision, and strategic goals 024 f) Amendments to BUT internal regulations in 2013 025 g) Providing information under Act no. 106/1999 Coll., concerning free access to information 026 03 DEGREE PROGRAMMES, STUDY ORGANISATION, AND EDUCATION 028 a) Accredited degree programmes (numbers in master groups according to study type and form) listed by faculty or other constituent parts offering an accredited degree programme or its part 029 b) Degree programmes taught in a foreign language by faculties or other constituent parts offering an accredited programme or part -

UNIVERSITY of OSTRAVA Department of Human Geography and Regional Development

UNIVERSITY OF OSTRAVA Department of Human Geography and Regional Development CONFERENCE MIGRATION AND DEVELOPMENT held in Ostrava on September 4th - 5th, 2007 The conference is supported by the European Social Fund PROGRAMME SCIENTIFIC BOARD CHAIRMAN Prof. Janos J. BOGARDI, Director of Institute for Environment and Human Security (UNU-EHS), United Nations University, Bonn, Germany BOARD MEMBERS AND KEY SPEAKERS Prof. Ronald SKELDON, Department of Geography, School of Social and Cultural Studies, University of Sussex, United Kingdom Prof. Graeme HUGO, Department of Geographical and Environmental Studies, The University of Adelaide, Australia Assoc. Prof. Dušan DRBOHLAV, Department of Social Geography and Regional Development, Faculty of Science, Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic Prof. J.A.(Tony) BINNS, Ron Lister Chair of Geography, Department of Geography, University of Otago, New Zealand Assoc. Prof. Jan KLÍMA, Cabinet of Iberoamerican Studies, Faculty of Humanities, University of Hradec Králové, Czech Republic Prof. Oscar Alvarez GILA, Facultad de Filología, Geografía e Historia, Universidad del País Vasco/University of the Basque Country, Spain Assoc. Prof. Tadeusz SIWEK, President of the Czech Geographical Union Department of Human Geography and Regional Development, Faculty of Science, University of Ostrava, Czech Republic François GEMENNE, M.A. et M.Res., Centre d'Etudes de l'Ethnicité et des Migrations (CEDEM), Université de Li`ege, Belgium; Centre d'Etudes et de Recherches Internationales (CERI), Institut d'Etudes Politiques -

Solid As a Rock

OKD Solid aS a rock www.okd.cz OKD Solid aS a rOcK Operations at one of Europe’s largest coal producers are underpinned by strong customer relationships, the continued implementation of top- class training and safety measures, and solid revenues and reserves written and researched by: RichaRd halfhide OKD oal represents the Czech Republic’s only significant indigenous energy resource; and as such, its importance Cto the economy in relation to export revenue and employment cannot be understated, and is as crucial today as it has been for the last two centuries. OKD operates as a subsidiary of New World Resources Plc (NWR), headquartered in the Netherlands and one of Central Europe’s leading hard coal and coke producers. As well as OKD, NWR also owns OKK Koksovny, a.s. (OKK), which is Europe’s largest producer of foundry coke. The company is listed on the London, Prague and Warsaw Stock Exchanges and can also be found on the FTSE 250 Mining Index. Today, OKD produces coking and thermal coal, mainly for the steel and energy sectors, and is the only producer of bituminous coal in the Czech Republic. As such, it represents both the history and the future of this most traditional of industries. A nod to the past is hard to ignore: generations of men have mined the same area in the Ostrava- Karviná, in the east of the country. “We are mining in old infrastructure: some of the shafts are close to 100 years old. The new shafts are 25 years old, but on average each is 40 to 50 years old,” says OKD’s CEO, Klaus Dieter-Beck. -

List of Erasmus+ Partner Institutions

List of Erasmus+ Partner Institutions LJMU School/Programme Partner Institution Art and Design Iceland Academy of Arts L' INSTITUT SUPERIEUR DES ARTS APPLIQUES Hochschule der Bildenden Kunste Saar Pecsi Tudomanyegyetem Marseille-Mediterranea College of Arts and Design Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam FH Joanneum - University of Applied Sciences Built Environment Danmarks Tekniske Universitet University Miskolc Middle East Technical University Anadalou Universitesi Istanbul Technical University University of Ostrava Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universitat Bonn Kauno Technologijos Universitetas Aleksandras Stulginskis University Vilnius Gediminas Technical University Latvia University of Agriculture Via University College Universidad de Oviedo Civil Engineering and Engineering Universidad de Oviedo and Technology Computer Science Hogeschool Gent Istanbul Technical University Education Tallinn University Universitat Rovira I Virgili Universitatea Babes-Bolyai, Cluj-Napcoa University of Gothenburg University of Eastern Finland Roskilde University Universitat Oldenburg University of Sassari University of Vic Engineering University College of Southeast Norway University of Balekesir KTH Royal Institute of Technology Angel Kunchev University of Rousse Gaziantep Universitesi Universitatea Politehnica Din Bucuresti Istanbul Technical University Humanities and Social Science Szegedi Tudomanyegyetem De Haagse Hogeschool Tischner European University/Wyzsza Szkola Europejsra Im. Ks. Jozefa Tischnera Universita' degli Studi di Napoli "L 'Orientale" University -

NWR Q1 09 Full Report FINAL

New World Resources Results for the first quarter 2009 Amsterdam, 18 May 2009 – New World Resources N.V. (“NWR” or the “Company”), Central Europe’s leading hard coal producer, today announces its unaudited financial results for the first quarter 2009. Highlights • Performance in Q1 2009 affected by deepening economic downturn in the CEE region with steel production in NWR’s markets down by 41%1, leading to considerably lower than expected sales volumes of coking coal and coke • Thermal coal sales revenues down by 2%, as higher prices partially offset the 16% decrease in volumes • Coal production of 3.1 Mt and net total sales of 2.0 Mt • Total coke production of 233 kt and total coke sales of 103 kt • Main operating expenses down by 12% in Q1 2009 year on year, excluding electricity trading • EBITDA down 72% to EUR 60 million • Adjusted loss per A share of EUR (0.01) • Unrestricted cash of EUR 557 million and no material refinancing requirements until 2012 • 2009 production targets reduced to 10.5 Mt of coal and 710 kt of coke in response to market conditions • Agreement with trade unions achieved, leading to an overall wage reduction for the full year 2009 and a headcount reduction of approximately 7%, including contractors, from current levels • POP 2010 programme continues to deliver better than expected improvements in efficiency and operational performance Chairman’s Statement “The global economic downturn has now severely impacted the industrial output in the CEE region with steel production in the region falling by some 41% compared to the same period in the previous year and with the outlook for the balance of 2009 remaining unclear.